Dark romanticism

| Fantasy |

|---|

|

| Media |

|

| Genre studies |

|

| Subgenres |

|

| Fandom |

|

| Categories |

|

|

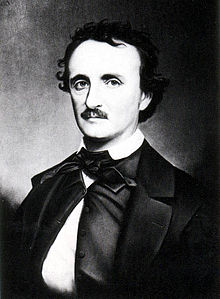

Dark Romanticism is a literary subgenre of Romanticism, reflecting popular fascination with the irrational, the demonic and the grotesque. Often conflated with Gothic fiction, it has shadowed the euphoric Romantic movement ever since its 18th-century beginnings. Edgar Allan Poe is often celebrated as one of the supreme exponents of the tradition.

Definitions[]

Romanticism's celebration of euphoria and sublimity has always been dogged by an equally intense fascination with melancholia, insanity, crime and shady atmosphere; with the options of ghosts and ghouls, the grotesque, and the irrational. The name "Dark Romanticism" was given to this form by the literary theorist Mario Praz in his lengthy study of the genre published in 1930, The Romantic Agony.[1][2]

According to the critic G. R. Thompson, "the Dark Romantics adapted images of anthropomorphized evil in the form of Satan, devils, ghosts, werewolves, vampires, and ghouls" as emblematic of human nature.[3] Thompson sums up the characteristics of the subgenre, writing:

Fallen man's inability fully to comprehend haunting reminders of another, supernatural realm that yet seemed not to exist, the constant perplexity of inexplicable and vastly metaphysical phenomena, a propensity for seemingly perverse or evil moral choices that had no firm or fixed measure or rule, and a sense of nameless guilt combined with a suspicion the external world was a delusive projection of the mind—these were major elements in the vision of man the Dark Romantics opposed to the mainstream of Romantic thought.[4]

18th- and 19th-century movements in different national literatures[]

Elements of dark romanticism were a perennial possibility within the broader international movement of Romanticism, in both literature and art.[5]

Germany[]

Dark Romanticism arguably began in Germany, with writers such as E. T. A. Hoffmann,[6] Christian Heinrich Spiess, and Ludwig Tieck – though their emphasis on existential alienation, the demonic in sex, and the uncanny,[7] was offset at the same time by the more homely cult of Biedermeier.[8]

Like the Gothic novel, Schwarze Romantik is a genre based on the terrifying side of the Middle Ages, and frequently feature the same elements (castles, ghost, monster, etc.). However, Schauerroman's key elements are necromancy and secret societies and it is remarkably more pessimistic than the British Gothic novel. All those elements are the basis for Friedrich von Schiller's unfinished novel The Ghost-Seer (1786–1789). The motive of secret societies is also present in Karl Grosse's Horrid Mysteries (1791–1794) and Christian August Vulpius's Rinaldo Rinaldini, the Robber Captain (1797).[9] Benedikte Naubert's novel Hermann of Unna (1788) is seen as being very close to the Schauerroman genre.[10]

Other early authors and works included Christian Heinrich Spiess, with his works Das Petermännchen (1793), Der alte Überall und Nirgends (1792), Die Löwenritter (1794), and Hans Heiling, vierter und letzter Regent der Erd- Luft- Feuer- und Wasser-Geister (1798); Heinrich von Kleist's short story "Das Bettelweib von Locarno" (1797); and Ludwig Tieck's Der blonde Eckbert (1797) and Der Runenberg (1804).[11]

Jüngere Romantik[]

During two decades, the most famous author of Gothic literature in Germany was the polymath E. T. A. Hoffmann. His novel The Devil's Elixirs (1815) was influenced by Lewis's The Monk and even mentions it. The novel also explores the motive of Doppelgänger, the term coined by another German author and supporter of Hoffmann, Jean Paul, in his humorous novel Siebenkäs (1796–1797). Aside from Hoffmann and de la Motte Fouqué, three other important authors from the era were Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff (The Marble Statue, 1819), Ludwig Achim von Arnim (Die Majoratsherren, 1819), and Adelbert von Chamisso (Peter Schlemihls wundersame Geschichte, 1814).[12] After them, Wilhelm Meinhold wrote The Amber Witch (1838) and Sidonia von Bork (1847). The last work from the German writer Theodor Storm, The Rider on the White Horse (1888), uses Gothic motives and themes.[13]

Britain[]

British authors such as Lord Byron, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Mary Shelley, and John William Polidori, who are frequently linked to Gothic fiction, are also sometimes referred to as Dark Romantics.[14] Dark Romanticism is characterized by stories of personal torment, social outcasts, and usually offers commentary on whether the nature of man will save or destroy him.[citation needed] Some Victorian authors of English horror fiction, such as Bram Stoker and Daphne du Maurier, follow in this lineage.

American[]

The American form of this sensibility centered on the writers Edgar Allan Poe, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Herman Melville.[15] As opposed to the perfectionist beliefs of Transcendentalism, these darker contemporaries emphasized human fallibility and proneness to sin and self-destruction, as well as the difficulties inherent in attempts at social reform.[16]

France[]

The 19th century fantastique literature after 1830 was dominated by the influence of E. T. A. Hoffmann, and then by that of Edgar Allan Poe. French authors such as Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly, Charles Baudelaire, Paul Verlaine and Arthur Rimbaud echoed the dark themes found in the German and English literature. Baudelaire was one of the first French writers to admire Edgar Allan Poe, but this admiration or even adulation of Poe became widespread in French literary circles in the late 19th century.

20th-century influence[]

Twentieth-century existential novels have also been linked to Dark Romanticism,[17] as too have the sword and sorcery novels of Robert E. Howard.[18]

Criticism[]

Northrop Frye pointed to the dangers of the demonic myth making of the dark side of romanticism as seeming "to provide all the disadvantages of superstition with none of the advantages of religion".[19]

See also[]

- Álvares de Azevedo

- Danse Macabre

- Doppelgänger

- Grotesque

- Nerval

- Noite na Taverna

- Satanism

- Ultra-Romanticism

References[]

- ^ First English translation 1933. The title in its original Italian is: "Carne, la morte e il diavolo nella letteratura romantica" (Flesh, death, and the devil in romantic literature".

- ^ Dark Romanticism: The Ultimate Contradiction Archived 2007-01-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Thompson, G. R., ed. "Introduction: Romanticism and the Gothic Tradition." Gothic Imagination: Essays in Dark Romanticism. Pullman, WA: Washington State University Press, 1974: p. 6.

- ^ Thompson, G.R., ed. 1974: p. 5.

- ^ Roland Borgards; Ingo Borges; Dorothee Gerkens; Claudia Dillmann (2012). Dark Romanticism: From Goya to Max Ernst. Distributed Art Pub Incorporated. ISBN 978-3-7757-3373-1.

- ^ A. Cusak/B. Murnane, Popular Revenants (2012) p. 19

- ^ S. Freud, 'The Uncanny' Imago (1919) p. 19-60

- ^ Stephen Prickett; Simon Haines (2010). European Romanticism: A Reader. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-4411-1764-9.

- ^ Cusack A., Barry M. (2012), Popular Revenants: The German Gothic and Its International Reception, 1800–2000, Camden House, pp. 10-17

- ^ Cussack, Barry, p. 10–16.

- ^ Hogle, p. 65-69

- ^ Cussack, Barry, p. 91, pp. 118–123.

- ^ Cussack, Barry, p. 26.

- ^ University of Delaware: Dark Romanticism

- ^ Robin Peel (2005). Apart from Modernism: Edith Wharton, Politics, and Fiction Before World War I. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-8386-4079-1.

- ^ T. Nitscke, Edgar Alan Poe's short story "The Tell-Tale Heart" (2012) p. 5–7

- ^ R. Kopley, Poe's Pym (1992) p. 141

- ^ Don Herron (1984). The Dark Barbarian: The Writings of Robert E Howard, a Critical Anthology. Wildside Press LLC. p. 57. ISBN 978-1-58715-203-0.

- ^ Northrop Frye, Anatomy of Criticism (1973) p. 157

Further reading[]

- Galens, David, ed. (2002) Literary Movements for Students Vol. 1.

- Harry Levin, The Power of Blackness (1958)

- Mario Praz The Romantic Agony (1933)

- Mullane, Janet and Robert T. Wilson, eds. (1989) Nineteenth Century Literature Criticism Vols. 1, 16, 24.

External links[]

- Romanticism

- Literary genres

- American literature

- Horror fiction

- 19th-century books

- Edgar Allan Poe