Human–animal hybrid

The terms human–animal hybrid and animal–human hybrid refer to an entity that incorporates elements from both humans and animals.[1][2][3][4][5]

Description[]

For thousands of years, these hybrids have been one of the most common themes in storytelling about animals throughout the world. The lack of a strong divide between humanity and animal nature in multiple traditional and ancient cultures has provided the underlying historical context for the popularity of tales where humans and animals have mingling relationships, such as in which one turns into the other or in which some mixed being goes through a journey.[6] Interspecies friendships within the animal kingdom, as well as between humans and their pets, additionally provides an underlying root for the popularity of such beings.[1]

In various mythologies throughout history, many particularly famous hybrids have existed, including as a part of Egyptian and Indian spirituality.[6] The entities have also been characters in fictional media more recently in history such as in H. G. Wells' work The Island of Doctor Moreau, adapted into the popular 1932 film Island of Lost Souls.[3] In legendary terms, the hybrids have played varying roles from that of trickster and/or villain to serving as divine heroes in very different contexts, depending on the given culture.[6]

For example, Pan is a deity in Greek mythology that rules over and symbolizes the untamed wild, being worshiped by hunters, fishermen, and shepherds in particular. The mischievous yet cheerful character is a Satyr who has the hindquarters, legs, and horns of a goat while otherwise being essentially human in appearance, with stories of his encounters with different gods, humans, and others being retold for centuries on after the days of early Greece by groups such as the Delphian Society.[7] Specifically, the human-animal hybrid has appeared in acclaimed works of art by figures such as Francis Bacon.[5] Additional famous mythological hybrids include the Egyptian god of death, named Anubis, and the fox-like Japanese beings that are called Kitsune.[6]

When looked at scientifically, outside of a fictional and/or mythical context, the real-life creation of human-animal hybrids has served as a subject of legal, moral, and technological debate in the context of recent advances in genetic engineering.[2][4][8] Defined by the magazine H+ as "genetic alterations that are blendings [sic] of animal and human forms", such hybrids may be referred by other names occasionally such as "para-humans".[1][2] They may additionally may be called "humanized animals".[8] Technically speaking, they are also related to "cybrids" (cytoplasmic hybrids), with "cybrid" cells featuring foreign human nuclei inside of them being a topic of interest. Possibly, a real-world human-animal hybrid may be an entity formed from either a human egg fertilized by a nonhuman sperm or a nonhuman egg fertilized by a human sperm.[2] While at first being a concept in the likes of legends and thought experiments, the first stable human-animal chimeras (not hybrids but related) to actually exist were first created by Shanghai Second Medical University scientists in 2003, the result of having fused human cells with rabbit eggs.[4] As well, a U.S. patent has notably been granted for a mouse chimera with a human immune system.[8]

In terms of scientific ethics, restrictions on the creation of human–animal hybrids have proved a controversial matter in multiple countries. While the state of Arizona banned the practice altogether in 2010, a proposal on the subject that sparked some interest in the United States Senate from 2011 to 2012 ended up going nowhere. Although the two concepts are not strictly related, discussions of experimentation into blended human and animal creatures has paralleled the discussions around embryonic stem-cell research (the 'stem cell controversy').[2] The creation of genetically modified organisms for a multitude of purposes has taken place in the modern world for decades, examples being specifically designed foodstuffs made to have features such as higher crop yields through better disease resistance.[9]

Despite the legal and moral controversy over the possible real-life making of such beings,[2][4][8] then President George W. Bush even speaking on the subject in his 2006 State of the Union,[10] the concept of humanoid creatures with hybrid characteristics from animals, played in a dramatic and sensationalized fashion, has continued to be a popular element of fictional media in the digital age. Examples include Splice, a 2009 movie about experimental genetic research,[2] and The Evil Within, a survival horror video game released in 2014 in which the protagonist fights grotesque hybrid creatures among other enemies.[11]

Legendary historical and mythological human-animal hybrids[]

Beings displaying a mixture of human and animal traits while also having a similarly blended appearance have played a vast and varied role in multiple traditions around the world.[6] Artist and scholar has written that "representations of human-animal hybrids always have their origins in religion". In "successive traditions they may change in meaning but they still remain within spiritual culture", Gaietto has argued, when looking back in an evolution-minded point of view. The beings show up in both Greek and Roman mythology, with various elements of ancient Egyptian society ebbing and flowing into those cultures in particular. Prominent examples in ancient Egyptian religion, featuring some of the earliest such hybrid beings, include the canine-like god of death known as Anubis and the lion-like Sphinx.[12][unreliable source?] Other instances of these types of characters include figures within both Chinese and Japanese mythology.[6][13] The observation of interspecies friendships within the animal kingdom, as well as the bonds existing between humans and their pets, have been a source of the appeal in such stories.[1]

A prominent hybrid figure that's internationally known is the mythological Greek figure of Pan. A deity that rules over and symbolizes the untamed wild, he helps express the inherent beauty of the natural world as the Greeks saw things. He specifically received reverence by ancient hunters, fishermen, shepherds, and other groups with a close connection to nature. Pan is a Satyr who possesses the hindquarters, legs, and horns of a goat while otherwise being essentially human in appearance; stories of his encounters with different gods, humans, and others have been a part of popular culture in several different cultures for many years.[7] The human-animal hybrid has appeared in acclaimed works of art by figures such as Francis Bacon,[5] also being mentioned in poetic pieces such as in John Fletcher's writings.[7]

In Chinese mythology, the figure of Chu Pa-chieh undergoes a personal journey in which he gives up wickedness for virtue. After causing a disturbance in heaven from his licentious actions, he is exiled to Earth. By mistake, he enters the womb of a sow and ends up being born as a half-man/half-pig entity. With the head and ears of a pig coupled with a human body, his already animal-like sense of selfishness from his past life remains. Killing and eating his mother as well as devouring his brothers, he makes his way to a mountain hideout, spending his days preying on unwary travelers unlucky enough to cross his path. However, the exhortations of the kind goddess Kuan Yin, journeying in China, persuade him to seek a nobler path, and his life's journey and the side of goodness proceeds on such that he even is ordained a priest by the goddess herself.[14] Remarking on the character's role in the religious novel Journey to the West, where the being first appears, professor Victor H. Mair has commented that "[p]ig-human hybrids represent descent and the grotesque, a capitulation to the basest appetites" rather than "self-improvement".[13]

Several hybrid entities have long played a major role in Japanese media and in traditional beliefs within the country. For example, a warrior god known as Amida received worship as a part of Japanese mythology for many years; he possessed a generally humanoid appearance while having a canine-like head. However, the god's devotional popularity fell in about the middle of the 19th century.[12][unreliable source?] A Tanuki resembles a raccoon or badger, but its shape-shifting talents allow it to turn into humans for the purposes of trickery, such as impersonating Buddhist monks. The fox-like creatures known as Kitsune also possess similar powers, and stories abound of them tricking human men into marriage by turning into seductive women.[6]

Other examples include characters in ancient Anatolia and Mesopotamia. The latter region has had the tradition of a malevolent human-animal hybrid deity in Pazuzu, the demon featuring a humanoid shape yet having grotesque features such as sharp talons.[12][unreliable source?] The character picked up revived attention when an interpretation of it appeared in William Peter Blatty's 1971 novel The Exorcist and the Academy Award winning 1973 film adaption of the same name, with the demon possessing the body of an innocent young girl. The movie, regarded as one of the greatest horror films of all time, has a prologue in which co-protagonist Father Merrin (Max von Sydow) visits an archaeological dig in Iraq and ominously discovers an old statue of the monstrous being.[15][16]

Theriocephaly[]

Theriocephaly (from Greek θηρίον therion 'beast' and κεφαλή kefalí 'head') is the anthropomorphic condition or quality of having the head of an animal – commonly used to refer the depiction in art of humans (or deities) with animal heads.[17] Many of the gods and goddesses worshipped by the ancient Egyptians, for example, were commonly depicted as being theriocephalic. Notable examples include:

- Horus, depicted as having the head of a falcon.

- Anubis, depicted with a jackal's head.

- The desert-god Set, often depicted with the head of an unknown creature, referred to as the Set animal by Egyptologists.

- Cernunnos, the Celtic deity adapted as the Horned God in Wicca.

- The Minotaur, from Greek mythology.

- In some Eastern Orthodox Church icon traditions, some saints, particularly St. Christopher, are depicted as having the head of a dog.

- In Hinduism, the wisdom god Ganesha is depicted with an elephant head.

- In Native American Abenaki mythology, the spirit Pamola was a being who possessed the head of a moose, and wings and taloned feet of an eagle.

More modern portrayals of fictional hybrids[]

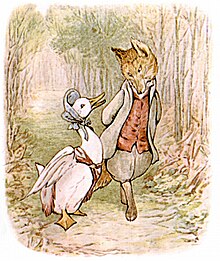

Many prominent pieces of children's literature over the past two centuries have featured humanized animal characters, often as protagonists in the stores. In the opinion of popular educator Lucy Sprague Mitchell, the appeal of such mythical and fantastic beings comes from how children desire "direct" language "told in terms of images— visual, auditory, tactile, muscle images". Another author has remarked that an "animal costume" provides "a way to emphasize or even exaggerate a particular characteristic". The anthropomorphic characters in the seminal works by English writer Beatrix Potter in particular live an ambiguous situation, having human dress yet displaying many instinctive animal traits. Writing on the popularity of Peter Rabbit, a later author commented that in "balancing humanized domesticity against wild rabbit foraging, Potter subverted parental authority and its built in hypocrisy" in Potter's child-centered books. Writer Lisa Fraustino has cited on the subject R.M. Lockley's tongue-in-cheek observation: "Rabbits are so human. Or is it the other way around— humans are so rabbit?"[18]

Writer H. G. Wells created his famous work The Island of Doctor Moreau, featuring a mixture of horror and science fiction elements, to promote the anti-vivisection cause as a part of his long-time advocacy for animal rights. Wells' story describes a man stuck on an island ruled over by the titular Dr. Moreau, a morally depraved scientist who has created several human-animal hybrids even by combining parts of other animals. The story has been adapted into film several times, with varying success. The most acclaimed version is the 1932 black-and-white treatment called Island of Lost Souls.[3]

Wells himself wrote that "this story was the response of an imaginative mind to the reminder that humanity is but animal rough-hewn to a reasonable shape and in perpetual internal conflict between instinct and injunction," with the scandals surrounding Oscar Wilde being the impetus for the English writer's treatment of themes such as ethics and psychology. Challenging the Victorian era viewpoints of its time, the 1896 work presents a complex situation in which enhancing animals into hybrids involves both terrifying violence and pain as well as appears essentially futile, given the power of raw instinct. A pessimistic view towards the ability of human civilization to live by law-abiding, moral standards for long thus follows.[19]

The 1986 horror film The Fly features a deformed and monstrous human-animal hybrid, played by actor Jeff Goldblum.[1] His character, scientist Seth Brundle, undergoes a teleportation experiment that goes awry and fuses him at a fundamental genetic level with a common fly caught besides him. Brundle experiences drastic mutations as a result that horrify him. Movie critic Gerardo Valero has written that the famous horror work, "released at the dawn of the AIDS epidemic", "was seen by many as a metaphor for the disease" while also playing on bodily fears about dismemberment and coming apart that human beings inherently share.[20]

The science fiction film Splice, released 2009, shows scientists mixing together human and animal DNA in the hopes of advancing medical research at the pharmaceutical company that they work at. Calamitous results occur.[2]

The H.P. Lovecraft inspired movie Dagon, released in 2001, additionally features grotesque hybrid beings. In terms of comic books, examples of fictional human-animal hybrids include the characters in Charles Burns' Black Hole series. In those comics, a set of teenagers in a 1970s era town become afflicted by a bizarre disease; the sexually transmitted affliction mutates them into monstrous forms.[1]

Multiple video games have featured human-animal hybrids as enemies for the protagonist(s) to defeat, including powerful boss characters. For instance, the 2014 survival horror release The Evil Within includes grotesque hybrid beings, looking like the undead, attacking main character Detective Sebastian Castellanos. With partners Joseph Oda and Julie Kidman, the protagonist attempts investigate a multiple homicide at a mental hospital yet discovers a mysterious figure who turns the world around them into a living nightmare, Castellanos having to find the truth about the criminal psychopath.[11]

Heroic character examples of human-animal anthropomorphic characters include the two protagonists of the 2002 movie The Cat Returns (Japanese title: 猫の恩返し), with the animated film featuring a young girl (named "Haru") being transformed against her will into a feline-human hybrid and fighting a villainous king of the cats with the help of a dashing male cat companion (known as the "Baron") at her side.

[]

Background and technological analyses[]

Broadly speaking, a hybrid being has one cell line throughout its entire body and came originally from a mix of entities, with different species involved to make a new genetic combination. For instance, a liger has a lion father and a tigress mother, such a creature only existing in captivity. Such hybridization has frequently caused difficult health problems that caregivers for the captive animals struggle with.[21]

A chimera is not the same thing as a hybrid because it is a being composed of two or more genetically distinct cell lines in one entity. The entity does not exist as a member of a separate species but has differing elements inside of it. An animal that has experienced an organ transplant or related surgery involving tissues from a different species is an example.[4]

Throughout past human evolution, hybridization occurred in many different instances, such as cross-breeding between Neanderthals and ancient versions of what are now modern humans. Some scientists have believed that particular genes of the Neanderthal may have been key to ancient humans' adaptation to the harsh climates they faced when they left Africa. However, mixing between species in the wild both now and through natural history have generally resulted in sterile offspring, thus being a dead end in reproductive terms.[21]

For much of modern history, the creation of genetically modified organisms in general was a topic rooted in fiction rather than practical research. This has changed significantly over the past few decades such that a number of plants and animals are commonly subject to genetic engineering for commercial purposes. For example, as of 2013 about 85% of the corn grown in the US as well as about 90% of its canola crops have been genetically modified.[9] As well, many Americans that have had cardiovascular surgery have had heart valves initially from pigs used in their procedures.[8]

Issues relating to possible human-animal hybrids outside of a fictional, historical, or mythic context but as real, engineered beings received major international attention in 2003, after some Chinese scientists at the Shanghai Second Medical University managed to successfully fuse human cells with rabbit eggs. The embryos formed reportedly were the first stable human-animal chimeras in existence. Research in similar areas continued into 2004 and 2005, with the topic picking up coverage from publications such as National Geographic News. The National Academy of Sciences soon began to look into the ethical questions involved.[4] The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office additionally stirred interest into the topic by granting a patent request for a genetically modified mouse with a human immune system.[8] Scientists announced in 2017 that they successfully created the first human-pig chimeric embryo. The embryo consisted mostly pig cells and some human cells. Scientists stated that they hope to use this technology to address the shortage of donor organs.[22][23] In July 2019, Japanese scientist got the approval of the Japanese government to experiment with inserting human stem cells into animal (particularly rodent) embryos.[24] Although its main use will be to make organ transplantation easier, this can be considered the first more effective step of making animal-human hybrids real. In April 2021, scientists reported the creation, for the first time, of human-monkey hybrid embryos.[25][26][27]

Legal and moral discussions[]

Advances in genetic engineering have generally caused a large number of debates and discussions in the fields related to bioethics, and research relating to the hypothetical creation of human-animal hybrids in the future has been no exception. The technical analyses of intermingling human-based and animal-based genetic material are ongoing; the ethical, moral, and legal issues arising from actual research using chimeras (rather than hybrids per se) at the moment also touch more speculative concerns as well. While laws against the creation of hybrid beings have been proposed in U.S. states and in the U.S. Congress, several scientists have argued that legal barriers might go too far and prohibit medically beneficial studies into human modification.[2][4][8] Although the two topics are not strictly related, the debates involving the creation of human-animal hybrids have paralleled that of the debates around the stem-cell research controversy.[2]

The question of what line exists between a 'human being and a 'non-human' being has been a difficult one for many researchers to answer. While animals having one percent or less of their cells originally coming from humans may clearly appear to be in the same boat as other animals, no consensus exists on how to think about beings in a genetic middle ground that have something like an even mix. "I don't think anyone knows in terms of crude percentages how to differentiate between humans and nonhumans," U.S. patent office official John Doll has stated.[8] Critics of increased government restrictions include scientists such as Dr. Douglas Kniss, head of the Laboratory of Perinatal Research at Ohio State University, who has remarked that formal laws aren't the best option since the "notion of animal-human hybrids is very complex." He's also argued that their creation is inherent "not the kind of thing we support" in his kind of research since scientists should "want to respect human life".[2] "There are chimeras out there that serve very valuable purposes in medical research, such as mice that make human antibodies," Michael Werner, the chief of policy for the Biotechnology Industry Organization, has commented.[8]

In contrast, notable socio-economic theorist Jeremy Rifkin has expressed opposition to research that creates beings crossing species boundaries, arguing that it interferes with the fundamental 'right to exist' possessed by each animal species. "One doesn't have to be religious or into animal rights to think this doesn't make sense," he has argued when expressing support for anti-chimera and anti-hybrid legislation. As well, William Cheshire, associate professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic's Florida branch, has called the issue "unexplored biologic territory" and advocated for a "moral threshold of human neural development" to restrict the destroying a human embryo to obtain cell material and/or the creation of an organism that's partly human and partly animal." He has said, "We must be cautious not to violate the integrity of humanity or of animal life over which we have a stewardship responsibility".[4]

In the U.S., efforts into creating a hybrid entity appeared to be legal when the topic first came up. The developmental biologist Stuart Newman, a professor at New York Medical College in Valhalla, N.Y., applied for a patent on a human-animal chimera in 1997 as a challenge to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office and the U.S. Congress, motivated by his moral and scientific opposition to the notion that living things can be patented at all. Prior legal precedent had established that genetically engineered entities, in general, could be patented, even if they were based on beings occurring in nature.[8]

After a seven-year process, Newman's patent finally received a flat rejection. The legal process had created a paper trail of arguments, giving Newman what he considered a victory. The Washington Post ran an article on the controversy that stated that it had raised "profound questions about the differences-- and similarities-- between humans and other animals, and the limits of treating animals as property."[8] President George W. Bush brought up the topic in his 2006 State of the Union Address, in which he called for the prohibition of "human cloning in all its forms", "creating or implanting embryos for experiments", "creating human-animal hybrids", and also "buying, selling, or patenting human embryos". He argued, "A hopeful society has institutions of science and medicine that do not cut ethical corners and that recognize the matchless value of every life." He also stated that humanity "should never be discarded, devalued or put up for sale."[10]

A 2005 appropriations bill passed by the U.S. Congress and signed into law by President Bush contained specific wording forbidding any patents on humans or human embryos.[8] In terms of outright bans on hybrid research in the first place, a measure came up in the 110th Congress entitled the Human-Animal Hybrid Prohibition Act of 2008. Congressman Chris Smith (R, NJ-4) introduced it on April 24, 2008. The text of the proposed act stated that "human dignity and the integrity of the human species are compromised" if such hybrids exist and set up the punishment of imprisonment for up to ten years as well as a fine of over one million dollars. Though attracting support from many co-sponsors such as then Representatives Mary Fallin, Duncan Hunter, Joseph R. Pitts, and Rick Renzi among others, the Act failed to get through Congress.[28]

A related proposal had come up in the U.S. Senate the prior year, the Human-Animal Hybrid Prohibition Act of 2007, and it also had failed. That effort was proposed by then-Senator Sam Brownback (R, KS) on November 15, 2007. Featuring the same language as the later measure in the House, its bipartisan group of cosponsors included then Senators Tom Coburn, Jim DeMint, and Mary Landrieu.[29]

A localized measure designed to ban the creation of hybrid entities came up in the state of Arizona in 2010. The proposal was signed into law by then Governor Jan Brewer. Its sponsor stated that it was needed to clarify important "ethical boundaries" in research.[2]

See also[]

- Animacy

- Alyoshenka

- Anthropomorphism

- Biopunk

- Chimera

- Furry fandom

- Gene therapy

- Genetic engineering

- Human–animal bonding

- Human–animal communication

- Human–animal studies

- Human enhancement

- Humanzee

- Hybrid

- Interspecies friendships

- Kemonomimi

- Legendary creature

- List of hybrid creatures in mythology

- Mary Toft

- Mythic animal

- Mythic humanoids

- Mythological hybrid

- Nephilim

- Otherkin

- Posthuman

- Talking animal

- Transhumanism

- Trial of Thomas Hogg

References[]

- ^ a b c d e f "Arts: The Parahuman Sculpture of Patricia Piccinini, Posthumanity and What It Really Means to be Human". H+. October 11, 2013. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Johnson, Alan (November 15, 2012). "Human-animal mix might become illegal". The Columbus Dispatch. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- ^ a b c Taylor, Drew (September 6, 2013). "Leonardo DiCaprio Looks to Produce 'Island of Dr. Moreau' Remake". news.moviefone.com. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Maryann, Mott (January 25, 2005). "Animal-Human Hybrids Spark Controversy". National Geographic News. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- ^ a b c Doyle, Richard (2003). Wetwares: Experiments in Postvital Living. University of Minnesota Press. p. 12.3. ISBN 9781452905846.

just you watch! pan.

- ^ a b c d e f g DeMello, Margo (2012). Animals and Society: An Introduction to Human-Animal Studies. Columbia University Press. pp. 301–211. ISBN 9780231152952.

- ^ a b c Rev. J.K. Brennan, ed. (1913). Hebrew literature. Greek mythology, life and art. Delphian Society. pp. 169–171.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Weiss, Rick (February 13, 2005). "U.S. Denies Patent for a Too-Human Hybrid". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- ^ a b Young, Caroline (February 2, 2014). "7 Most Common Genetically Modified Foods". The Huffington Post. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- ^ a b "President Bush's State of the Union Address – CQ Transcripts Wire". The Washington Post. January 31, 2006. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- ^ a b Dornbush, Jonathon (October 21, 2014). "Despite occasional brilliance, 'Evil Within' falls short of its horror game predecessors". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- ^ a b c (2014). Phylogensesis of Beauty. Lulu Press Inc. pp. 190–192. ISBN 9781291842951.

- ^ a b Victor H. Mair (2013). The Columbia History of Chinese Literature. Columbia University Press. p. 129. ISBN 9780231528511.

- ^ E.T.C. Werner. "Myths & Legends of China". Project Gutenberg. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- ^ Holtzclaw, Mike (October 24, 2014). "The sound and fury of 'The Exorcist'". Daily Press. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- ^ Susman, Gary (December 26, 2013). "'The Exorcist': 25 Things You Didn't Know About the Terrifying Horror Classic". news.moviefone.com. Archived from the original on December 27, 2013. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- ^ Agamben, Giorgio (2004). The Open. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4738-5.

- ^ Lisa R. Fraustino (2014). Dr. Claudia Mills (ed.). Ethics and Children's Literature. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 145–162. ISBN 9781472440723.

- ^ Neville Hoad (2004). Lauren Gail Berlant (ed.). Compassion: The Culture and Politics of an Emotion. Psychology Press. pp. 187–212. ISBN 9780415970525.

- ^ Valero, Gerardo (January 13, 2014). "David Cronenberg's "The Fly"". rogerebert.com. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- ^ a b Palmer, Roxanne (July 25, 2013). "Zonkey, Wholphin, Liger, Tigon: Fascinating Animal Hybrids". International Business Times. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- ^ "Human-Pig Hybrid Created in the Lab—Here Are the Facts". January 26, 2017. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ Wu, Jun; Platero-Luengo, Aida; Sakurai, Masahiro; Sugawara, Atsushi; Gil, Maria Antonia; Yamauchi, Takayoshi; Suzuki, Keiichiro; Bogliotti, Yanina Soledad; Cuello, Cristina; Valencia, Mariana Morales; Okumura, Daiji (January 26, 2017). "Interspecies Chimerism with Mammalian Pluripotent Stem Cells". Cell. 168 (3): 473–486.e15. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.036. ISSN 0092-8674. PMC 5679265. PMID 28129541.

- ^ Cyranoski, David (July 26, 2019). "Japan approves first human-animal embryo experiments". Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-019-02275-3. PMID 32710002.

- ^ Subbaraman, Nidhi (April 15, 2021). "First monkey–hum.an embryos reignite debate over hybrid animals – The chimaeras lived up to 19 days — but some scientists question the need for such research". Nature. Retrieved April 16, 2021.

- ^ Tan, Tao; et al. (April 15, 2021). "Chimeric contribution of human extended pluripotent stem cells to monkey embryos ex vivo". cell. 184 (8). doi:10.1016/j.cell.2021.03.020. Retrieved April 16, 2021.

- ^ Wells, Sarah (April 15, 2021). "Researchers Generate Human-Monkey Chimeric Embryos - Don't worry, there are not human-monkey babies — yet". . Retrieved April 16, 2021.

- ^ "H.R. 5910 (110th): Human-Animal Hybrid Prohibition Act of 2008". GovTrack. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- ^ "S. 2358 (110th): Human-Animal Hybrid Prohibition Act of 2007". GovTrack. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

External links[]

- "Chinese Human-animal Hybrid Embryo Experiments Have Been Interrupted" – Sina.com report (Chinese language)

- "The First Individual Animal-hybrid Embryos Are From China" – Xinhua News Agency report (Chinese language)

- Animals in mythology

- Anthropomorphism

- Animals and humans

- Biopunk

- Genetic engineering

- Human-derived fictional species

- Furry fandom

- Hybrid animals

- Mammal hybrids

- Mythic humanoids

- Mythological characters

- Mythological human hybrids

- Mythological hybrids

- Science fantasy

- Thought experiments

- Transhumanism