David Berman (musician)

This article or section is being initially created, or is in the process of an expansion or major restructuring. You are welcome to assist in its construction by editing it as well. This template was placed by DMT Biscuit (talk · contribs). If this article or section , please remove this template. If you are the editor who added this template and you are actively editing, please be sure to replace this template with {{in use}} during the active editing session. Click on the link for template parameters to use.

This article was by ( | contribs) 24 minutes ago. () |

David Berman | |

|---|---|

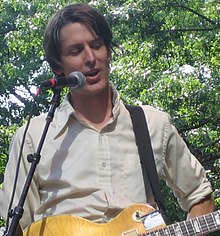

Berman performing at All Tomorrow's Parties in 2008 | |

| Born | January 4, 1967 Williamsburg, Virginia, US |

| Died | August 7, 2019 (aged 52) Brooklyn, New York City, U.S. |

| Alma mater | University of Virginia University of Massachusetts Amherst |

| Occupation |

|

| Years active | 1989–2009, 2019 |

| Spouse(s) | Cassie Berman (1999–2018) |

| Parents |

|

| Musical career | |

| Origin | Hoboken, New Jersey |

| Genres | Country-rock |

| Instruments |

|

| Labels | |

| Associated acts | |

David Cloud Berman (David Craig Berman; January 4, 1967 – August 7, 2019) was an American musician, singer and poet. In 1989, with Pavement's Stephen Malkmus and Bob Nastanovich, he founded the indie rock band Silver Jews, and was its only constant member during the band's career, which concluded in 2009 following their sixth album Lookout Mountain, Lookout Sea (2008). He provided the band's characteristic lyrics and with Malkmus, the simple, country-rock sound they developed from their early lo-fi recordings.

Actual Air, Berman's only published volume of poetry, was released in 1999, by which time he had become dependent on heroin and crack cocaine. Eventually, his struggle with substance abuse, depression and anxiety overcame his career decisions, and he attempted suicide in 2003. After, he underwent rehabilitation, engaged with Judaism, and with his wife Cassie Berman, he toured for the first time.

Although Berman's music and poetry were relatively successful, his life was marred by financial difficulties which, along with the dissolution of his marriage, resulted in his return to music in 2019. He adopted a new band name Purple Mountains, released an eponymous debut album that July, and planned for a tour to pay off a $100,000 credit card debt. He died by suicide in August 2019.

Despite Berman thinking his music was unappreciated, he developed a reputation as a revered lyricist. His abstract and later autobiographical lyrics were his creative priority; he extensively labored over them and sang them in a deep, monotone manner. His work cultivated a passionate following and he became an influential figure in indie rock.

Biography[]

Early life[]

David Craig Berman was born on January 4, 1967, in Williamsburg, Virginia.[1] He came from a secular Jewish family, whom he had said were neither religious, literary nor artistic; his father, Richard Berman, is a lobbyist who represents firearms, alcohol, and other industries.[2][a] He did not know or interact with many Jews during his childhood but sympathized with the supposed alienation.[5]

Berman's parents divorced when he was seven, and he would periodically live with both of them; his mother moved to Ohio, to become a teacher, while against Berman's wishes, he and his father moved to Dallas, Texas—a decision reportedly propelled by Berman then-appearing to become meek.[6] Berman has described his childhood as "grindingly painful" and asserted that he was "mostly independent of family things", having disliked his father from a young age.[7]

Berman attended high school at Greenhill School in Addison, Texas, and then the University of Virginia.[8] As a teenager, per his father's decision, he was sent to a psychiatrist. Berman was diagnosed with depression, which was later discovered to be treatment-resistant. Berman began smoking PCP every day of his second year of college.[9] He was, by his own admission, too lazy to apply for college so his father's secretary applied on Berman's behalf.[10]

To Berman, Dallas was a source of musical inspiration, later reflecting upon it with strong apperciation; he took an interest in a rare Fairlight keyboard and bands like Art of Noise, Prefab Sprout, X, the Replacements, the Cure, New Order, and Echo and the Bunnymen.[11] In high school, he began experimenting with poetry by writing to girlfriends, considering the line "A cartoon lake. Wolf on skates" to be his first true foray into poetry.[12] Berman hoped for his poetry to resemble the lyrics of Jello Biafra and Exene Cervenka, with lyrics being his primary inspiration.[13]

At university, Berman met Stephen Malkmus, Bob Nastanovich, and James McNew.[1] Malkmus, Nastanovich, and Berman frequently went to shows, brought records, and discussed obscure bands—Malkmus and Berman first met when they carpooled together to attend a concert.[14] The quartet formed Ectoslavia.[15] The band eventually became Berman's, Malkmus and Nastanovich having been excluded.[16]

Origin of Silver Jews: 1989–1994[]

Upon graduation, Berman, Malkmus, and Nastanovich moved to Hoboken, New Jersey, where they shared an apartment.[17] In 1989, they adopted the band name Silver Jews and recorded discordant tapes in their living room.[18][b] Around this time, Malkmus and Berman worked as security guards at New York's Whitney Museum of American Art; they would "get high" on their lunch breaks and Berman would write lyrics and poems while working—Malkmus would occasionally act as co-writer alongside Berman.[20] According to Berman's long-time friend Kevin Guthrie, Malkmus and Berman had a harmonious friendship, and Nastanovich revered both artists' creativity.[21] "It was mostly drinking beer and seeing grunge bands" Malkmus said regarding this time period; Berman recalled a diminished sense of being auethentically Jewish.[22]

Berman begrudged Silver Jews being sometimes viewed as a side-project to Malkmus' band Pavement but the connection led to Berman signing with indie label Drag City, which would later release all of his albums—the Pavement relation was responsible for them amassing a "national audience".[23] The band's first extended-plays (EPs) Dime Map of the Reef and The Arizona Record were not commercially successful but gained them attention in a cult-like manner; Kim Gordon was an admirer and Will Oldham said Dime Map of the Reef inspired him to send recordings to Drag City.[24][c] He later characterized his resentment at the erroneous perception of Silver Jews as entitled, noting by 2000 it was less of an issue.[26]

Following the EPs, Berman began studying for a master's degree in poetry at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.[27] Dubbing this time an "academic exile", Matthew Shaer, in a 2006 Boston Globe article, speculated that Berman's extended time studying may have been an attempt to distance himself from Pavement.[28] He tried to get a substantial amount of poems published in the American Poetry Review but was roundly rejected—which increased his interest in music, "despite scarcely knowing how to sing or play guitar".[29] As of 2005, Berman's public appearances mostly consisted of poetry readings.[30][d]

By October 1994, Silver Jews had enough material for their debut album Starlite Walker, which established respect in the indie rock scene, although with some detractors.[32] Malkmus and Nastanovich's involvement with Pavement meant they were unavailable for the next Silver Jews album The Natural Bridge, and only Berman and Peyton Pinkerton continued writing for it.[33] Pavement's success proved difficult for Berman, who became suspicious of fame and resented the people with whom he interacted, deeming them "cruel" and feeling somewhat abandoned by Malkmus and Nastanovich, although he understood the circumstances permitted little else.[34] Berman's personal life was affected by the deaths of friends, which would influence his songwriting.[35]

Silver Jews was part of a "moment in underground music" of songwriters who looked to the 1970s and 1980s for inspiration, and were one of Drag City's seminal groups alongside Smog, Pavement, Royal Trux, and Palace, bands that "made American music frightening again by tapping into its most tangled roots".[36] Berman wished to "distinguish his brand of songwriting from the depressive-narcissistic strain of 1990s rock" and later sought to break away from Drag City's "cryptic and prankish" style.[37] The line-up of Silver Jews constantly changed around Berman, who remained its principal songwriter and "main creative driver", having led the band's creative direction since the start.[38]

Critical acclaim and substance abuse: 1996–2001[]

The composition of The Natural Bridge (1996) left Berman distraught; he appeared to be "haunted by ghosts" and was hospitalized with sleep deprivation.[39] "When the songs were being recorded, things got darker in my life", he recollected, in an aloof manner, also noting that "recording was a process of calming myself down".[40] According to Oldham, the album's producer Mark Nevers "had sort of held Berman’s hand".[41] Although it received positive reviews in music publications—Berman having now "established himself as a world-class rock lyricist"—he chose not to tour due to a fear of performing.[42] After The Natural Bridge, Berman decided he wanted Malkmus and Nastanovich, both of whom felt betrayed by Berman's hostility toward them, to be involved with all subsequent Silver Jews albums.[43]

The resulting pain helped Berman, alongside Malkmus, to formulate a new Silver Jews album American Water; it was significant to Berman and the band's progression—now "stepped out of Pavement's shadow...clearly his project[,] represent[ing] his vision", his songwriting having been at the foreground of the former album. They gained further attention and critical acclaim.[44][e] Berman's drug use continued; using them during studio sessions. Despite his personal turmoil, Berman wanted the album to be joyous like "other people['s] records" rather than grim. The band intended to tour in late 1998 but plans were ended after a fistfight led to Berman's eardrum rupturing.[39]

Actual Air, Berman's first collection of poetry, was released in 1999 by Open City Books, which had been founded to publish the collection.[47] Amassing critical acclaim—Carl Wilson called it "even better than [Berman's] albums"—the book's unusually high sales of over 20,000 copies bolstered Berman's musical career.[48] Actual Air's marketing was akin to that of an album, which contributed to its success; Drag City and record stores were the avenues from which a "significant portion of those sales" arose.[49] In 2001, he was offered a job as poet-in-residence on a postgraduate course; the prospect thrilled Berman however he chose not to apply out of apprehension.[50] Although he sporadically published poems in the following years—his poetry being featured in journals such as The Baffler, Open City and The Believer—and had reported working on a follow-up, Actual Air remained his only book of poetry.[51] In his later years, Berman stopped writing poetry though a lack of motivation and a feeling of partial inadequacy in comparison to younger poets; another collection failed to materialize due to a lack of purpose and innovation.[52]

Around this time, Berman, who no longer "[had] to work", estimated he made $23,000 a year; in 2001, he had made $45,000 from his music.[53] That year, the album Bright Flight, which included Berman's wife Cassie Berman, was released. Their relationship started two years earlier at a party; Berman awoke in Cassie's house and learned she owned all of the then-released Silver Jews albums.[54] Cassie was a source of relief for Berman and she helped him feel young, later considering their relationship the "best thing that ever happened to me".[55] The two lived in Nashville for 19 years, moving to aid Berman's music career.[56]

After being introduced to hard drugs in 1998, Berman suffered an intense period of depression and substance abuse, during which he was using crack cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine.[57] The next year, amid other deaths of Berman's friends, his friend Robert Bingham died of a heroin overdose.[58] His use of crack reached the point of addiction.[59] He twice unintentionally overdosed; one incident followed the release party for Bright Flight and his struggles resulted in a darker sound on the album than on the band's earlier releases.[60]

Attempted suicide, rehab and career progession: 2003–2008[]

On November 19, 2003, Berman attempted suicide in Nashville by consuming crack cocaine, alcohol and tranquilizers.[1] He wrote a short note to Cassie—the brevity of which Berman would later regret—put on his wedding suit, and went to a "crack house" he frequented. When discovered by Cassie, he verbally lashed out and refused treatment. He was eventually taken to Vanderbilt University Medical Center, awakening three days later.[30]

Around a year later, Berman checked in for drug rehabilitation, which was paid for by his father, and encouraged by his mother and Cassie. Berman said he had relapsed but that by August 2005 he was not using drugs.[61] During his rehabilitation, Berman embraced Judaism, choosing to study the Torah and sought to be a "better person" who was "easier" to Cassie and staff at Drag City.[62] Reflecting upon his suicide, five years later, Berman noted that he was not unprivileged and without career opportunities, although this was not evident at the time.[63] He began to excessively take antidepressants and his sobriety made him more receptive to candidness.[64]

A year after Berman's rehabilitation, and by means of "saving [himself]", Silver Jews, with a lineup including Cassie, Malkmus, Nastanovich, Bobby Bare Jr., Paz Lenchantin, and William Tyler, released Tanglewood Numbers.[65] Soon after, the band began to tour, with 100 shows from 2006 to 2009 taking place; to cope with the hectic nature, he became "a daily pot smoker", in defiance of his sobriety.[66][f] Before Berman toured, he occasionally made caricatures of fans, considering it more rewarding.[50]

By this time, Silver Jews had sold 250,000 records.[47][g] Berman and Cassie still experienced financial difficulties; Cassie worked an office job and Berman struggled to get medical insurance for the removal of a keratoconus, eventually acquiring it from the Country Music Association.[69] In 2005, Jeremy Blake enlisted Berman for Sodium Fox, an artwork centered around Berman.[70] Blake's suicide and Berman's eye operation would affect the next Silver Jews album, Lookout Mountain, Lookout Sea, released in 2008 to lukewarm reviews.[71][h][i] During this period, Berman forewent his past reservations and the band became more prosperous, their latest album being their most successful.[75]

Berman's decision to tour, no longer dependent on drugs, was based upon his greater age—which to him meant he was "uncorruptable"—his expanded discography, and the infuriation caused by separation from his audience. Although he said meeting fans is "not necessarily nutritional for your creativity" doing so "softened his naturally gruff exterior" and was a highlight for him; touring was otherwise "a spiritual and intellectual deadzone".[76][j] Berman found touring with Cassie eased the experience, considering her a necessary component, noting that if he was alone he'd likely act to his detriment.[80]

Hiatus from music: 2009–2017[]

On January 22, 2009, Berman announced that Silver Jews would disband, their final show to be played the following week at Cumberland Caverns in McMinnville, Tennessee. "I always said we would stop before we got bad", he wrote.[81] During the performance at Cumberland Caverns, Berman said; "I always wanted to go out on top, but I much prefer this".[82] The band's end "caused a stir in US indie rock circles"; according to Nashville Scene's Sean L. Maloney, following Silver Jews' impact on Nashville's mid-2000s music scene, the final show meant "a chapter in this city’s artistic evolution closed".[83][84]

Berman also announced he was the son of lobbyist Richard Berman.[85] Berman considered this his "gravest secret", viewing his father as markedly loathsome.[81][86] In 2005, Berman said he owed his father $10,000 and his father used this against Berman whenever they argued.[68] The year before, he donated to Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington under the impression it was investigating Richard.[87] He would be estranged from his father by 2006.[88] Upon considering the commercialization of modern musicians, Berman began to see his and Richard's lives intertwining.[89] This, alongside his guilt about his father, were the reasons he retired Silver Jews, saying:

This winter I decided that [Silver Jews] were too small of a force to ever come close to undoing a millionth of all the harm he has caused … Previously I thought through songs and poems and drawings I could find and build a refuge away from his world, but there is the matter of Justice. And I’ll tell you it’s not just a metaphor. The desire for it actually burns. It hurts. There needs to be something more.[90]

After Silver Jews disbanded, Berman became a recluse; his few public appearances included a poetry reading and a screening of Trash Humpers. He worked on his blog "Menthol Mountains" and read about politics, history, and religion.[91][92][93][94][k] His public perception became intertwined with fabrications—significant speculation upon the events of his suicide attempt had reportedly occurred before this time.[96][97] In 2009, Berman published a book of surreal, minimalist cartoons called The Portable February to mixed reviews.[98][99][100][l] The "hermit, solitary aspect to the way [Berman] live[d]" predated this time, according to a 2008 interview—and Nastanovich reflected two years earlier that Berman had "gotten more reclusive".[102][103] Cassie sought a career in pediatric therapy.[104]

In 2010, Berman spoke about his difficulties with writing a book about his father and that HBO had expressed an interest in adapting the book. A screenwriter was hired and a pilot script was written. HBO wanted to begin production but Berman canceled it, saying he did not want to glamorize his father.[105] By attempting to document his father's life, he sought to become his "nemesis".[89] In an article about Berman, Derek Robertson said; "he lived much of his life in a more explicit [than his music] rebuke to his father, putting as much distance between himself and institutional power as he could".[106] According to Thomas Beller, Berman's disdain of his father was "grounded in politics and also in a thicket of personal motivations".[105]

Berman worked with German artist Friedrich Kunath on the book You Owe Me a Feeling, which features paintings and poetry by Kunath and Berman, respectively.[107] After the death of his friend Dave Cloud in 2015, Berman changed his middle name from Craig to Cloud.[108] Berman's mother died the following year, leading him to write the song "I Loved Being My Mother's Son", which appeared on his next album.[109] During this time, Berman continued to write but he "didn’t pick up a guitar for seven years".[110] He was still in contact with Malkmus, had a close relationship with Silver Jews drummer Brian Kotzur, and, according to Nastanovich, at one point intended to write new Silver Jews songs, for an undisclosed purpose, however, "in typical fashion, he sort of bailed on the idea of writing songs like that anymore, and it was during this period he got into writing (for other people)".[111][112][113]

Purple Mountains and death: 2018–2019[]

If Silver Jews closed out their career with odes to the open field of possibility, Berman here inaugurated what would have been a different artistic phase with a series of songs about the disappointments of expectations unfulfilled.

— Jewish Currents' Nathan Goldman, on Berman's new disposition.[114]

In 2018, Berman and Cassie separated, and from June he lived in a room above Drag City's Chicago offices because he lacked enough money to live elsewhere.[115] According to Berman, they "never had the kind of conflict that results in divorce" but had a "kind of need to live [their] lives without the other one".[116] Berman thought his chronic depression meant he was "unfit to be anyone's husband".[117] He and Cassie maintained the same bank account and owned a house together; Berman considered her his family and was "all [he] had".[116]

Berman briefly lived in Miller Beach and spent early 2017 in Gary, Indiana.[115][109] At one point, he asked a friend to give him heroin; the request was refused, for which Berman was ultimately grateful,[109] having not used heroin or cocaine since October 2003.[118] He had grown disillusioned with Judaism in relation to his isolation, saying his belief in God lasted from 2004 to 2010.[115][119] In 2008, he voiced a disconnect from Judaism: "I’m not Jewish. In a way 'silver Jews' has become a category for me of someone who’s a fellow traveler of the Jews ... A non-Jew applying for status".[120][m]

In 2018, Berman co-produced Yonatan Gat's album Universalists, having met Gat during a 2006 tour of Israel and helped get him signed to Drag City.[122][123] Following the release of two singles under his new moniker Purple Mountains, an eponymous debut album was released in July 2019.[124] The album was "Instantly mythologized" and Berman received heightened attention and very positive reviews: "Purple Mountains looked like the start to an unexpected second act for David Berman".[125][126][127] Berman worked on Purple Mountains with Woods and Berman's friend Dan Auerbach,[93] with whom he had worked in 2015.[128] Auerbach has called Berman "one of [his] heroes".[129]

Berman's financial difficulties, the dissolution of his marriage, and encouragement from Drag City's president Dan Koretzky were impetuses for Berman's new music.[109][92][130] At that time, Berman was living off royalties from Drag City.[131] The album was likely to be his most successful release. Berman hoped to resolve the $100,000 of loan and credit card debt he had amassed[109][132] as a result of his drug use; in a 2005 interview, he said; "I've got a credit card rotisserie system that would dazzle the ancients".[68][133] He stated this was the only reason he intended to tour, having expressed worries about the tour and notified the accompanying band his depression may be an interference but he was excited for his "solitude to end".[109][131][134]

In June 2019, Berman said: "There were probably 100 nights over the last 10 years where I was sure I wouldn't make it to the morning".[116] Berman died on August 7, 2019, having hanged himself in an apartment in Park Slope, Brooklyn, New York.[135] It is unclear whether Berman's suicide was spontaneous or deliberated upon; according to The Philadelphia Inquirer's Dan DeLuca; "The warning signs were all over Purple Mountains".[136][137] A private funeral attended by "Friends and family, along with the Jewish community" took place on August 16th.[138]

Tributes[]

Many artists paid tribute to Berman following his suicide. Malkmus and Nastanovich both commented on his death and performed shows in his honor.[139][140][141] Drag City released a musical tribute to Berman, a cover of "The Wild Kindness", sung by Bill Callahan, Will Oldham, and Cassie Berman.[142] Cover albums titled Approaching Perfection: A Tribute To DC Berman and Late Homework: The Songs of David Berman were released two months after his death.[143]

The Avalanches—with whom Berman collaborated in 2012 and 2016[144]—Fleet Foxes, Mogwai, Daniel Blumberg, The Mountain Goats, and Cassandra Jenkins paid tribute on their respective albums We Will Always Love You, Shore, As the Love Continues, On&On, Dark in Here and An Overview on Phenomenal Nature.[145][146][147][148][149][150] John Vanderslice released an EP titled I can't believe civilization is still going here in 2021! Congratulations to all of us, Love DCB as a tribute to Berman.[151]

Kunath hosted an art show he and Berman worked on.[107] Filmmaker Lance Bangs announced a memorial at New York's , the former location of the Whitney.[139] The Tennessee Titans, Berman's favorite football team, displayed a message saying "Nashville (and the world) will always love David Berman" on its Jumbotron.[152] Fans shared lyrics on social media and major publications wrote obituaries and tributes.[125][136] "In the wake of Berman’s death ... His voice never felt louder or more vital", wrote Pitchfork's Sam Sodomsky.[153] The 62nd Annual Grammy Awards' memorial reel's exclusion of Berman was criticized.[154]

Speaking of his son's death, Richard Berman said; "Despite his difficulties, he always remained my special son. I will miss him more than he was able to realize."[155]

Artistry[]

Lyrics[]

Having abandoned albums because he was unable to complete the lyrics, Berman spent the most time of his creative process on them, to the point of obsession, feeling his musical skills were inadequate when compared with his peers like Jack White; Koretzky reportedly saw Berman spend months working on a single line.[91][109][93] Berman's process involved considering his audience's understanding; he juxtaposed his abstract lyrics with simple melodies and rhyme schemes.[162][163] He recalled a disconnect to his audience—"an indie rock crowd"—while writing Bright Flight due to the "sick, sick, despairing, falling apart lives" of his associates. Berman deemed all of this a "major problem".[164] He had a didactic approach with Tanglewood Numbers and Lookout Mountain, Lookout Sea, wanting to give "instructions" on forgoing depression with the former.[73][165] Mark Richardson, writing for Pitchfork, and Randall Roberts of the Los Angeles Times, noted Berman's proficiency for minimalist compression.[166][167][o]

Berman's songs often use country music tropes and tend to focus on music, nature, beauty, disconnection, drugs, sports, America and god—religion is present in every Silver Jews album and Purple Mountains evokes a "Jewish mystical idea about the paths to God as a despondent parable".[92][125][152][114][168][169] An influence on his writing, Berman thought highly of America although hoped for a "redemption".[92][119][170] Berman's artistic perception of America has been noted as idiosyncratic, narrow and poignant.[97][171][172][173]

From Bright Flight onwards his lyrics became autobiographical, within a dramatic framework, the preceeding work being to him "make-believe"; on Tanglewood Numbers, he documented his struggle with substance abuse.[174][175][176] Roberts called Purple Mountains "nearly as autobiographical as a memoir".[162][167] Berman discussed his isolation, divorce—Silver Jews songs about Cassie having been plentiful—and death, which had a particular presence.[168][125][156] On all of the Silver Jews albums, Berman made use of "stand-ins for [his] own estrangement", his characters composed of traits originating from either real-life people, fictional characters or archetypes.[177][178] His fictional narratives often start relatively straightforwardly and then become bizarre; the songs of American Water conjure an "absurdist landscape" and "grow more obtuse in proportion to tunefulness".[74][179] His stories present a literary aesthetic that is "equal parts rural shack and gothic zen".[180]

After garnering a greater audience from Actual Air, Berman's lyrics began to be held to a higher standard; he's been praised for diverging from his peers.[174][181][72] Per his lyrics, he's been credited with significantly influencing indie rock.[162][155][182][183] Pitchfork deemed him one of "the most influential" musicians who were active around the end of the 20th century and beyond.[184]

Sound[]

Silver Jews' early work is defined by an ultra lo-fi aesthetic, first starting as ostensibly "avant-gardist" within the framework of "traditional" pop songs.. Their work before Starlite Walker, which they recorded at a professional studio and saw them drop this aesthetic in favor of an experimental-oriented, country-rock sound, is "regarded as the lowest fidelity recordings of the first lo-fi movement".[91][77][185][186] The changing line-up influenced the sound, Berman's musical approach became simplified and the band moved further towards a country sound; according to Goldman, "Even the most country moments ... have a punk-rock edge", a style he found does not apply to Purple Mountains.[187][166][114] Purple Mountains is Berman's most direct, conventional album, although all of his discography is relatively conventional.[162][188] Berman's vocal delivery was deadpan, brusque and mostly uninflected—his register was baritone and he would concurrently sing and speak.[109][90][174][125][189] Reviewing Starlite Walker for The Guardian, Jonathan Romney described Berman's approach as "whiny, archetypally slackerish" with "vaguely country inflections"—the early country aspects being mostly humorous.[190][191]

Silver Jews' songs were often sparse and deceptively simple, usually with three or four chords, the kind Berman said "you might learn in beginner’s guitar lessons".[115][131][168] Berman understood his musical abilities were limited, the nature of which was initially obscured by the lo-fi sound.[115][109][174][191] For a while, he questioned as to why he was without natural talent, eventually renouncing his self-consciousness.[192][164] His austere style proved to be influential.[193]

In 2001, Berman said that he had gone "months, sometimes years without [using his guitar]" and said his process of creating albums started in his mind and then he would "go at it every day for a few hours until the album's done".[166] For the first four Silver Jews albums, Berman wrote all the songs—to Malkmus' gratitude who comparative to Pavement played more melodic and simple material.[194][195][156] He would typically write the music first and then the lyrics.[196] Having been Berman's "longtime musical foil", Malkmus and his approach to music differed.[115][161] With Tanglewood Numbers, Berman exercised greater care and control, in regards to its final state—Shaer observed soon after its release that the album "represents Berman's most comprehensive effort to focus his songwriting".[194][102]

During concerts, Berman's and Cassie's performances were often symbiotic, the pair "shar[ing] a brightening chemistry"; Cassie's calm disposition provided stability to Berman's electric presence.[93][197] According to Dazed's Nick Chen, in a performance documented on Silver Jew, Berman was "a natural showman, [making] gestures with his arms that accentuate the punchiness and the hard consonants of the sing-a-long verses".[198] Berman also performed in a rigid manner, reading sheet music "like it’s a literary reading".[199] Marc Hirsh of the Boston Globe said Berman used a music stand to create a barrier between himself and the audience.[200]

Poetry[]

In a 2002 profile, Berman, who "[made] art out of hostility", stated that "I started writing poems because I wanted to make poems so good they would make everyone else quit. I don't have the voice or the technical skills to blow people away with my music. But I have a chance to do that with my poetry".[187] Although his lyrics and poetry remain distinct from each other,[201] they share similar characteristics:[99][169][196][202][89][203][204][205]

- direct delivery

- literary wit

- observations that are occasionally mundane and reference aspects of pop culture such as Judas Priest, Woolite, and James Michener

- picturesque descriptions

- allusions to Judeo-Christianity

- forsaken subjects

- and themes of Americana, absurdism and everyday melancholy.[p]

Unlike his music, Berman's poetry did not feature rhyme and the poems in Actual Air were written in free verse and various styles of prose.[206][207][208] Berman noted a static, conventional, nature to his poetry—greater than his music—in which there are "no left hooks and speeding trains".[209] He composed his poems using written notes.[115] Berman preferred to write music because he found poetry offered too much freedom.[119]

James Tate, under whom Berman studied, said the poems are "narratives that freeze life in impossible contortions", whereas Berman called them "psychedelic soap operas".[196] Heidi Julavits noted that Berman often distorted familiar concepts in his poetry.[210] Writing with direct attention on emotions, Actual Air's poems include small-scale scenes and situations he extensively explores; the world he concocted is eccentric—with "plausible contexts" quickly altered by "an odd word" and domestic scenes "twinged with gothic weirdness"; the collection, which treads "between surrealism and confession", "reads like a novel written in two-sentence paragraphs".[205][207][208][211][212][213][214][q] As does his music, Berman's poetry features an entanglement of reality and symbolism, often in the form of civic imagery.[215]

Berman's poetry was praised by Dara Wier and Billy Collins—the latter featuring him in a poetry anthology.[210][136] Rich Smith of The Stranger summarized Berman's poetic output as a "master[y of] the opening line, the surprising image, the lyric narrative, the warm abstraction, and the crucial skill of knowing when to use the Latin word or the German word".[216] Speaking on his reception, the NME's Emily Baker said Berman is "regarded by many as one of American’s foremost [contemporary] poets".[217] Sophie Best, in a 2005 article for The Age, said he was "famous as one of those rare creatures—a published poet with credentials and sales".[218] Aaron Calvin, in an article for Pitchfork, wrote that the intersection of Berman's lyrics and poetry "fuels" his legacy.[201]

Image and self-perception[]

Here was a man too brilliant for his own health, held captive by unseen forces.[158]

— the perception of Berman's career, as defined by the opening lyrics to Random Rules, and as articulated by Marc Hogan of Pitchfork

Berman was acutely aware of his public image and feared after the release of Purple Mountains he would be seen as a "sad sack", and had earlier wished his persona to appear less abrasive.[93][219][131] He kept note of musicians who had mentioned him in interviews and believed his music was unappreciated, having "always been his own smallest fan".[131][220] Berman viewed Silver Jews as not a "band that other bands would namedrop", distinct from the likes of Smog or Oldham, which Berman was appreciative for.[103] Although he once conveyed a need for outside validation, he refused to read reviews or articles concerning him; by 2005, hoping for his self-perception to be independent from others, he had installed an external blocking device on his computer for this very reason.[221][31] In music and poetry, Berman felt his peers saw him as "moonlighting"—he once expressed an interest in being "a stranger" in both fields.[222][196][r]

Although he'd later just consider himself an artist, Berman had been surprised that his songwriting gained more attention than his poetry, thinking of himself as more a poet than a songwriter; "his cult following knew Berman as a serious poet", wrote Wilson in 2008 and his status as "a real-deal poet" led to him being "something of an anomaly in the music world".[174][224][225][79]

Berman was seen as a "cult hero" due in part to his aversion to promotion and his initial refusal to tour—which Berman found accidental—generated a sense of mystique.[226][198][93][s] According to Nastanovich, Berman was "not a good self-promoter. He [was] a poet and songwriter, not a business man."[115] Berman was "An archetypal Gen X-er"—as he "[could not] be bothered to sell [his art]"; he relied upon word of mouth and positive reviews.[77][227] He expressed ambivalence toward his inability to reach a larger audience "beyond indie circles", where he amassed a reputation as "perhaps the finest lyricst of his generation" with his diligence being a frequent point of discussion.[131][228][229][t]

Timothy Michalik of Under The Radar said Berman had a simultaneously low-brow and high-brow persona to which fans could relate.[99][u] According to Adam Rothband of Tiny Mix Tapes, Berman "felt synonymous with what he created, as if his songs and his poetry were him".[188] Berman's return to music prompted a jovial and personal response from major publications, with concern for Berman having been identifed as instrumental to his fervent fanbase.[220][201][232] The perception of Purple Mountains was significantly altered following Berman's suicide:"it['s] impossible to hear this album in any other context", "Now, instead of worrying, you mourn".[233][234][235]

Influences[]

Berman said his influences include Tate—discernible in Actual Air per style and focus upon location and person; Russell Edson, Kenneth Koch, Ben Katchor, Bruce Nauman, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Sherri Levine, Louise Lawler, Wallace Stevens, Charles Wright, and Emily Dickinson.[175][196][103][208] Studying the Torah helped him learn more about poetry.[73]

Discography[]

- Silver Jews

- Starlite Walker (1994)

- The Natural Bridge (1996)

- American Water (1998)

- Bright Flight (2001)

- Tanglewood Numbers (2005)

- Lookout Mountain, Lookout Sea (2008)

- Purple Mountains

- Purple Mountains (2019)

Bibliography[]

- Actual Air (1999)

- The Portable February (2009)

Notes[]

- ^ Berman identified as "ethnically Jewish" but not religious for most of his life.[3] His mother's status as a convert whose conversion was not supervised by an Orthodox rabbi, hindered Berman's full embrace of Judaism in later life.[4]

- ^ On the band's early recordings, Malkmus and Nastanovich used aliases.[19]

- ^ The similar but greater status of Berman's later music would aid him in recruiting musicians to perform with him.[25]

- ^ His means of deciding the locations for a set of readings, the year prior, was composed of multiple reasons: a favor for Drag City and Open City, a desire to visit where he had not been before and resulting stopover at an old friend's house; to benefit the "Arkansas literacy project" and to be "the object of an assembly [at Greenhill School]".[31]

- ^ The album's creation, which took four days, also affected Malkmus, making him "realize that there’s such a better way to be making records" than he had before.[45] American Water would be an inspiration for the Pavement album, Terror Twilight.[46]

- ^ Their first tour was documented in the 2007 film Silver Jew.[67]

- ^ Berman said he made $16,000 in 2004, from his first four albums.[68]

- ^ Carl Wilson, retroactively, speculated that the album's reception may have contributed towards the Silver Jews' end.[72]

- ^ "Candy Jail" and "My Pillow is the Threshold" concern Blake's death.[73][74]

- ^ At a younger age, Berman thought of touring as too significant a commitment and considered the stress to be intolerable, in contrast to his new-found acceptance.[77][78] Playing live appeared to him as "like some unnecesary post-invention marketing effort" and had not elicited much "satisfaction" in the past.[77][79]

- ^ A 1996 article described Berman's then-daily routine as follows: "Every day he helps cultivate water melons in his five-acre garden, reads a book and keeps company with his beloved dog, Jackson".[95]

- ^ Berman had composed a book of drawings beforehand, which inspired the title of Pavement's debut album, Slanted and Enchanted.[101]

- ^ Goldman and Arielle Angel of Jewish Currents would reflect upon Berman saying that he represented Jews "spiritually" and "positionally", and people they dubbed "Silver Jews". In his withdrawal, they said he "[fixed] himself in Jewish tradition".[121]

- ^ Dan Bejar, who worked with Berman in the early recording sessions of Purple Mountains, reflected that their once was "lots of really wild lines that would have fit in more with ’90s Berman—just blasting images, more manic, which was actually the state he was in". As the process continued, Berman became disinterested in said lyrical material, hoping to explore new avenues, and resultingly abandoning the pervious work.[161]

- ^ Richardson compared it to a haiku and Roberts noted it was used in Lookout Mountain, Lookout Sea for "universal themes of life, death and finding meaning in-between".[166][167]

- ^ According to Ethan A. Paquin, Berman "examine[d] the pathos underpinning banal scenery and situations" with a focus upon "beauty and transcendence".[203]

- ^ Berman and Roberts identified a "miniature" quality to Berman's poetry.[209][211]

- ^ He said similar of Nick Cave and Richard Hell, whose novels Berman felt were "contextualised as 'moonlighting'" as a result of their musical careers, affecting "how the books were actually read".[223]

- ^ As of 2005, Silver Jews had only purchased one advertisement in Alternative Press in 1994, for .[68] He reportedly refused to let Drag City promote his music.[97]

- ^ Eric Clark of The Gazette, in his review for Lookout Mountain, Lookout Sea, said the lo-fi sound of Silver Jews' music "kept the band miles away from the mainstream for most of its existence".[230] Writing for Rolling Stone, Ted Drozdowski recognized the lo-fi sound as a by-product of the band being determined to release music: "they'll record with bearskins and flints if that gets the music out".[231]

- ^ Berman felt to be an artist, he had to "exist in a time where high and low art mix easily".[74]

References[]

- ^ a b c Cartwright 2019. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCartwright2019 (help)

- ^ Cartwright 2019 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCartwright2019 (help); Blume 2006 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBlume2006 (help); Barshad 2008 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBarshad2008 (help).

- ^ Friedman, Gabe (August 8, 2019). "David Berman, indie rocker known for fronting band the Silver Jews, dead at 52". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. Archived from the original on August 23, 2021. Retrieved August 23, 2021.

- ^ Kaufmann, David (June 11, 2008). "The Reciprocal Antagonist". The Forward. Archived from the original on August 24, 2021. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ^ Barshad 2008 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBarshad2008 (help); Davidson 2006.

- ^ Blume 2006 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBlume2006 (help); Tucker 2005 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFTucker2005 (help); Lingan 2019 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFLingan2019 (help).

- ^ Freeman 2008; Kofman 2015.

- ^ Bailey 2008.

- ^ Tucker 2005 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFTucker2005 (help); Marchese 2019; Edwards 1998 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFEdwards1998 (help).

- ^ Kornhaber 2019a.

- ^ Kavanagh 2020 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFKavanagh2020 (help); Lingan 2019 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFLingan2019 (help); Tucker 2005 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFTucker2005 (help).

- ^ Poetry Society of America Writer n.d.

- ^ Marx 2008. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFMarx2008 (help)

- ^ Bryan 2010, p. 27; Blume 2006 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBlume2006 (help).

- ^ Kavanagh 2020. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFKavanagh2020 (help)

- ^ Bryan 2010, p. 27.

- ^ Deluca 2018.

- ^ Stolworthy 2019; Deluca 2018.

- ^ Oakes, Kaya (June 9, 2009). Slanted and Enchanted: The Evolution of Indie Culture. Henry Holt and Company. p. 140. ISBN 978-1-4299-3572-2.

- ^ DeLuca 2008; Hinson 2008 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFHinson2008 (help); Kornhaber 2019b.

- ^ Valania 2001; Nashville Scene Writer 2019.

- ^ Timberg 2004 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFTimberg2004 (help); Feldman 1997 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFFeldman1997 (help).

- ^ Cartwright 2019 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCartwright2019 (help); Shteamer & Newman 2019 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFShteamerNewman2019 (help); Pfafflin 2002.

- ^ Cartwright 2019 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCartwright2019 (help); Weiden 2005; Gross 2019 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFGross2019 (help).

- ^ Guarino, Mark (April 14, 2006). "The Silver Jews with Why?". The Daily Herald. Archived from the original on September 13, 2021. Retrieved September 13, 2021.

- ^ Assar 2006.

- ^ Larson 2019; Mason 2005 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFMason2005 (help).

- ^ Shaer 2006. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFShaer2006 (help)

- ^ Smith 2019. sfn error: multiple targets (3×): CITEREFSmith2019 (help)

- ^ a b Weiden 2005.

- ^ a b Tucker, Ashford (April 15, 2004). "Berman Reads his Poems at the College of Charleston". The Post and Courier. Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- ^ Larson 2019; Smith 2019 sfnm error: multiple targets (3×): CITEREFSmith2019 (help).

- ^ Cartwright 2019 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCartwright2019 (help); Rutledge 2019 sfnm error: multiple targets (4×): CITEREFRutledge2019 (help).

- ^ Weiden 2005; Wagons 2019, 6:50-7:20.

- ^ Hyden 2019a.

- ^ Powell 2017; Raymond 2009.

- ^ Dollar 2008b; Lucas 2018 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFLucas2018 (help).

- ^ Tucker 2005 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFTucker2005 (help); Kornhaber 2019b; Shteamer & Newman 2019 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFShteamerNewman2019 (help); Blume 2006 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBlume2006 (help).

- ^ a b Powell 2017.

- ^ Feldman 1997 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFFeldman1997 (help); Lewis 1996.

- ^ Licht 2012, p. 159.

- ^ Cartwright 2019 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCartwright2019 (help); Hart 2019 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFHart2019 (help).

- ^ Walsh 2016.

- ^ Powell 2017; Hogan & Sodomsky 2019; Sheffield 2019 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFSheffield2019 (help); Masters 2010; Wilson 2001 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWilson2001 (help).

- ^ Valania 2001.

- ^ Sheffield, Rob (April 12, 2001). "Cool rock: Stephen malkmus". Rolling Stone. Retrieved November 4, 2021.

- ^ a b Mason 2005. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFMason2005 (help)

- ^ Lingan 2019 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFLingan2019 (help); Mason 2015; Oakes 2009, p. 146 sfnm error: multiple targets (5×): CITEREFOakes2009 (help); Wilson 2002.

- ^ Elaine 2000. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFElaine2000 (help)

- ^ a b Costa 2002. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCosta2002 (help)

- ^ Kavanagh 2020 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFKavanagh2020 (help); Timberg 2004 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFTimberg2004 (help); Tucker 2004 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFTucker2004 (help).

- ^ Kavanagh 2020 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFKavanagh2020 (help); Diver & Wolstenholme 2008 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFDiverWolstenholme2008 (help).

- ^ Tucker 2005 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFTucker2005 (help); Richardson 2002 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFRichardson2002 (help); Oakes 2009, p. 148 sfnm error: multiple targets (5×): CITEREFOakes2009 (help).

- ^ Howe 2005; Malitz 2019 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFMalitz2019 (help); Barshad 2008 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBarshad2008 (help).

- ^ Kissinger 2006; Goldsmith 2019 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFGoldsmith2019 (help).

- ^ Nashville Scene Writer 2019; Paulson 2019.

- ^ Cartwright 2019 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCartwright2019 (help); Lingan 2019 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFLingan2019 (help); Wilson 2019 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWilson2019 (help).

- ^ Lingan 2019 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFLingan2019 (help); Sackllah 2019 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFSackllah2019 (help).

- ^ Roberts 2019 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFRoberts2019 (help); Levisohn 2005.

- ^ Weiden 2005; Nichols 2019 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFNichols2019 (help); Malitz 2019 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFMalitz2019 (help).

- ^ Blume 2006 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBlume2006 (help); Tucker 2005 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFTucker2005 (help).

- ^ Cartwright 2019 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCartwright2019 (help); Weiden 2005.

- ^ Marvar 2008. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFMarvar2008 (help)

- ^ Dollar 2008b; Wilson 2008 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWilson2008 (help).

- ^ Hogan & Sodomsky 2019; Howe 2005; DeLuca 2008.

- ^ Kavanagh 2020 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFKavanagh2020 (help); Nichols 2019 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFNichols2019 (help).

- ^ Riesman 2019. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFRiesman2019 (help)

- ^ a b c d Tucker, Ashford (August 8, 2005). "Silver Jews". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ^ Currin 2008.

- ^ Hertz 2007.

- ^ Shteamer & Newman 2019 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFShteamerNewman2019 (help); Wilson 2019 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWilson2019 (help); Marvar 2008 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFMarvar2008 (help); Kelly 2008 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFKelly2008 (help).

- ^ a b Wilson, Carl (July 11, 2019). "The Greatest Songwriter You've Never Heard of Is Back". Slate. Archived from the original on July 14, 2019. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ a b c Dollar, Steve (June 15, 2008). "David Berman Finds Comfort In His Own Head". The New York Sun. Archived from the original on October 18, 2016. Retrieved September 25, 2021.

- ^ a b c Kelly, Jennifer (June 16, 2008). "Clearer Vision: An interview With David Berman of the Silver Jews, PopMatters". PopMatters. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved May 14, 2021.

- ^ Lingan 2019 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFLingan2019 (help); Malitz 2019 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFMalitz2019 (help); Beller 2012 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBeller2012 (help).

- ^ Marvar 2008 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFMarvar2008 (help); Brinn 2006.

- ^ a b c d Feldman, Steve (May 1, 1997). "Listen Up: Rocker Proving His Mettle With Silver Jews". Jewish Exponent. Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:53was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Truman, Deanna (October 9, 2008). "Q&A with David Berman". Iowa City Press-Citizen.

- ^ Diver & Wolstenholme 2008 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFDiverWolstenholme2008 (help); Brinn 2006.

- ^ a b Philips, Amy (January 23, 2009). "Silver Jews' David Berman Calls It Quits". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on June 24, 2017. Retrieved August 18, 2014.

- ^ Rodgers, D. Patrick. "The Year in Music: Top Shows | Silver Jews in the Cave". Nashville Scene. Archived from the original on August 19, 2021. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ Maloney, Sean L. (August 16, 2019). "Exploring the Majesty of Purple Mountains". Nashville Scene. Archived from the original on August 19, 2021. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ Hunter-Tilney, Ludovic (July 12, 2019). "Purple Mountains: Purple Mountains—David Berman is back". Financial Times. Archived from the original on September 25, 2021. Retrieved September 25, 2021.

- ^ Michaels, Sean (January 26, 2009). "Silver Jews frontman dissolves band to oppose his Washington lobbyist father". The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 23, 2021. Retrieved August 23, 2021.

- ^ Staff, Harriet (August 20, 2021). "The wild kindness vs. the dedicated evil". Poetry Foundation. Archived from the original on August 20, 2021. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ Lozano, Alice (January 27, 2009). "David Berman calls it quits, lambastes father on Drag City website". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on August 11, 2021. Retrieved September 25, 2021.

- ^ Devinantz, Victor G. (2010). "The 'Rogue Employer Thesis' Revisited: The Fallacy Behind The Center for Union Facts' 'Union Math, Union Myths'". Labor Law Journal. 61 (1).

- ^ a b c Bergen, Mark (July 26, 2010). "Punk in the Beerlight". Tablet. Archived from the original on August 29, 2021. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ a b Shteamer, Hank; Newman, Jason (August 7, 2019). "Silver Jews' David Berman Dead at 52". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on August 8, 2019. Retrieved August 8, 2019.

- ^ a b c Cartwright, Garth (August 9, 2019). "David Berman obituary". The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved March 12, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Kornhaber, Spencer (August 13, 2019). "David Berman Saw the Source of American Sadness". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on January 30, 2021. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Malitz, David (June 3, 2019). "David Berman was the cult musician who went away for 10 years. What made him finally come back?". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on February 7, 2021. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- ^ Sodomsky, Sam (July 12, 2019). "Purple Mountains: Purple Mountains". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on April 23, 2021. Retrieved April 23, 2021.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:76was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Hinson, Mark (September 12, 2008). "Poet-singer David Berman paid his dues with Silver Jews". Tallahassee Democrat.

- ^ a b c Lucas, Madelaine (August 22, 2018). "I Only Want To Die In Your Eyes". The Believer. Archived from the original on September 26, 2021. Retrieved September 26, 2021.

- ^ Beaumont-Thomas, Ben (August 8, 2019). "David Berman, acclaimed US indie songwriter, dies aged 52". The Guardian. Archived from the original on November 27, 2020. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- ^ a b c Michalik, Timothy (August 9, 2019). "On the Last Day of Your Life, Don't Forget to Die: Remembering David Berman". Under The Radar. Archived from the original on January 31, 2020. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

- ^ Ivry, Sara (July 9, 2009). "Silver Jew Is Genius Cartoonist, Or Not". Tablet. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ Robbins, Ira (1997). "Pavement". Pulse!.

- ^ a b Shaer, Matthew (March 19, 2006). "Stepping out of the shadows". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on August 24, 2021. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ^ a b c Newlin, Jimmy (June 15, 2008). "Interview: David Berman on Silver Jews's Lookout Mountain, Lookout Sea". Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on May 12, 2021. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ^ Bishop, Syd (November 28, 2018). "Louisville native and former Silver Jews bassist Cassie Berman joins Hotel Ten Eyes". Louisville Eccentric Observer. Archived from the original on September 25, 2021. Retrieved September 25, 2021.

- ^ a b Beller, Thomas (December 13, 2012). "A Tribute to David Berman, The Silver Jews' Genius of Free Association, on the Occasion of his Yahrtzeit". Tablet. Archived from the original on September 25, 2021. Retrieved September 25, 2021.

- ^ Robertson, Derek (December 29, 2019). "David Berman: The Poet of Gen X's Tortured Political Consciousness". Politico. Archived from the original on August 24, 2021. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ^ a b Yoo, Noah (November 14, 2019). "Drag City Announces New Art Show Inspired by David Berman's Music". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on August 5, 2020. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ^ Rutledge, Chris (July 10, 2019). "Purple Mountains: Any Way You Hear It". American Songwriter. Archived from the original on July 10, 2019. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Lingan, John (July 10, 2019). "David Berman Returns". The Ringer. Archived from the original on December 8, 2020. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- ^ Writer, Aquarium Drunkard (July 8, 2019). "David Berman : The Aquarium Drunkard Interview". Aquarium Drunkard. Archived from the original on January 17, 2021. Retrieved September 18, 2021.

- ^ Stewart, Allison (April 1, 2016). "Between Pavement and Silver Jews, Bob Nastanovich had difficulties". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved October 23, 2021.

- ^ Wolk, Douglas (June 9, 2011). "Post-pavement tour, stephen malkmus goes L.A. with beck". Rolling Stone. Retrieved November 4, 2021.

- ^ Khomami, Nadia (February 19, 2015). "Stephen Malkmus rejects Pavement bandmates' reunion offer". NME. Retrieved November 4, 2021.

- ^ a b c Goldman, Nathan (August 9, 2019). "David Berman's Parting Gift". The Nation. ISSN 0027-8378. Archived from the original on September 15, 2021. Retrieved September 15, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kavanagh, Adalena (January 31, 2020). "An Interview with David Berman". Believer. Archived from the original on January 21, 2021. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

- ^ a b c Khanna, Vish (June 27, 2019). "David Berman Discusses Every Song on Purple Mountains' Self-Titled New Album". Exclaim!. Archived from the original on December 20, 2020. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ Goldsmith, Mike (July 9, 2019). "Simply The Everest: Ex-Silver Jews man returns to extend his appeal beyond the cult". Record Collector. Archived from the original on August 24, 2021. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ^ Moon, Mark E. (August 10, 2021). "Bitter Memories of David Berman's Suffering Linger 2 Years After His Suicide". Dallas Observer. Archived from the original on August 19, 2021. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ a b c Gross, Julie (August 14, 2019). "Remembering David Berman, Leader Of Silver Jews And Purple Mountains". Louisville Eccentric Observer. Archived from the original on February 14, 2021. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ Barshad, Amos (June 17, 2008). "The Silver Jews' David Berman Is Currently Accepting Intern Applications". Vulture. Archived from the original on September 17, 2021. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- ^ Angel, Arielle; Goldman, Nathan (August 9, 2019). "Kaddish for David Berman". Jewish Currents. Archived from the original on December 15, 2020. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ Bonner, Michael (August 8, 2019). "Tributes paid to Silver Jews' David Berman, who has died aged 52". Uncut. Archived from the original on August 8, 2019. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ Dollar, Steve (April 16, 2008). "Wild and Crazy Guys". The New York Sun.

- ^ "David Berman's Purple Mountains reveals debut album: Stream". Consequence. July 12, 2019. Archived from the original on August 23, 2021. Retrieved August 23, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Sackllah, David (August 8, 2019). "Remembering David Berman, An Artist Who Often Approached Perfection". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ Bobkin, Matt (December 4, 2019). "Exclaim!'s 20 Best Pop and Rock Albums of 2019 | Purple Mountains Purple Mountains (Drag City)". Exclaim!. Archived from the original on May 13, 2020. Retrieved October 7, 2021.

- ^ Ruttenberg, Jay (June 6, 2020). "Woods Strange To Explain". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on October 9, 2021. Retrieved October 9, 2021.

- ^ Camp, Zoe (November 23, 2015). "The Black Keys' Dan Auerbach's the Arcs Share "Young", Written With Silver Jews' David Berman". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ^ Rodman, Sarah (December 9, 2015). "Dan Auerbach's career takes new Arcs". The Boston Globe. Retrieved October 23, 2021.

- ^ Hart, Otis (August 7, 2019). "Silver Jews' David Berman Dies At 52". NPR. Archived from the original on March 13, 2021. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Hyden, Stephen (August 8, 2019). "David Berman Was One Of Indie's Greatest Songwriters". Uproxx. Archived from the original on November 27, 2020. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- ^ Jenkins, Dafydd (August 6, 2019). "Purple Mountains – the eventual return of Silver Jews' David Berman". Loud and Quiet. Archived from the original on August 8, 2019. Retrieved August 8, 2019.

- ^ Oakes, Kaya (June 9, 2009). Slanted and Enchanted: The Evolution of Indie Culture. Henry Holt and Company. p. 148. ISBN 978-1-4299-3572-2.

- ^ Currin, Grayson Haver (May 19, 2020). "Woods Became David Berman's Band. Then They Picked Up the Pieces". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 7, 2021. Retrieved October 7, 2021.

- ^ Aniftos, Rania (August 9, 2019). "David Berman's Cause of Death Revealed". Billboard. Archived from the original on August 21, 2019. Retrieved September 11, 2019.

- ^ a b c Pfarrer, Steve (September 25, 2019). "Remembering David Berman: Late singer-songwriter and poet had key ties to the Valley". Daily Hampshire Gazette. Archived from the original on September 25, 2021. Retrieved September 25, 2021.

- ^ DeLuca, Dan (December 14, 2019). "The best albums of 2019, with Lana Del Rey, Brittany Howard, Nick Cave, and more". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Archived from the original on October 9, 2021. Retrieved October 9, 2021.

- ^ Writer, The Tennessean (August 14, 2019). "David Berman Obituary (1967 - 2019)". The Tennessean. Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- ^ a b Minsker, Evan (August 8, 2019). "Silver Jews' David Berman Remembered by Stephen Malkmus, Bob Nastanovich, Bill Callahan, Kurt Vile, More". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on January 17, 2021. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ^ Ruiz, Matthew Ismael (December 18, 2019). "Stephen Malkmus and Bob Nastanovich to Perform at David Berman Tribute Show in Portland". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on March 18, 2021. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ^ Arcand, Rob (January 5, 2020). "Stephen Malkmus and Bob Nastanovich Cover David Berman Songs at Birthday Memorial Show". Spin. Archived from the original on April 19, 2021. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ Strauss, Matthew (February 19, 2021). "Bill Callahan, Bonnie "Prince" Billy, and Cassie Berman Cover Silver Jews' "The Wild Kindness"". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on April 2, 2021. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

- ^ Gregory, Allie (October 18, 2019). "David Berman Celebrated with Another Tribute Compilation". Exclaim!. Archived from the original on August 22, 2021. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- ^ Henry, Dusty (August 8, 2019). "R.I.P. David Berman of Silver Jews and Purple Mountains". KEXP. Archived from the original on August 21, 2021. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ Spin Staff (March 18, 2020). "The Avalanches Share 'Running Red Light' Featuring Rivers Cuomo and Pink Siifu". Spin. Archived from the original on March 21, 2021. Retrieved March 28, 2021.

- ^ Strauss, Matthew (September 23, 2020). "Fleet Foxes: Shore". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ Trendell, Andrew (January 12, 2021). "Mogwai share beautiful 'Ritchie Sacramento' video and talk 'positive' new album". NME. Archived from the original on February 27, 2021. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

- ^ Bray, Elisa (July 30, 2020). "Album reviews: The Psychedelic Furs and Daniel Blumberg". The Independent. Archived from the original on March 1, 2021. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ Dolan, Jon (June 29, 2021). "Mountain Goats Mix Terror and Beauty on 'Dark in Here'". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on July 4, 2021. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- ^ Grant, Sarah (April 2, 2021). "Cassandra Jenkins, In Bloom". Spin. Archived from the original on July 29, 2021. Retrieved July 29, 2021.

- ^ Albertson, Jasmine (July 15, 2021). "John Vanderslice Breaks Down His Dark and Feverish Tribute EP to David Berman (KEXP Track-By-Track)". KEXP. Archived from the original on July 15, 2021. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ a b Sodomsky, Sam (November 11, 2019). "David Berman Gets Tribute at Tennessee Titans Football Game". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on February 2, 2021. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ^ Sodomsky, Sam (October 8, 2019). "The 200 Best Albums of the 2010s | Purple Mountains: Purple Mountains (2019)". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on March 14, 2020. Retrieved October 7, 2021.

- ^ Clarke, Patrick (January 27, 2020). "Keith Flint, Scott Walker and more omitted from Grammys' 'In Memoriam' video". NME. Archived from the original on October 21, 2020. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ a b Kennedy, Mark (August 9, 2019). "David Berman, founder of indie rockers Silver Jews, dies". Associated Press. Archived from the original on April 17, 2021. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ a b c Rutledge, Chris (July 10, 2019). "The Natural Bridge: A Silver Jews Primer". American Songwriter. Archived from the original on August 27, 2021. Retrieved August 27, 2021.

- ^ Meyer, Jack (July 23, 2020). "The 15 Best David Berman Songs | 1. "Random Rules"". Paste. Archived from the original on September 17, 2021. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

:12was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Terich, Jeff (December 8, 2014). "Lyric Of The Week: Silver Jews, "Random Rules"". American Songwriter. Archived from the original on September 17, 2021. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- ^ Sodomsky, Sam (May 17, 2019). ""All My Happiness Is Gone"". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on October 7, 2021. Retrieved October 7, 2021.

- ^ a b Dombal, Ryan (January 14, 2020). "Destroyer's Dan Bejar Serenades the Apocalypse". Pitchfork. Retrieved October 28, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Kornhaber, Spencer (August 8, 2019). "David Berman Sang the Truth". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on March 1, 2021. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- ^ Diver, Mike; Wolstenholme, Gary (June 14, 2008). "Silver Jews' David Berman in conversation". Drowned In Sound. Archived from the original on May 15, 2021. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- ^ a b Malitz, David (June 27, 2008). "Post Rock Podcast: David Berman of Silver Jews, Part 3 - Post Rock". Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 29, 2021. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- ^ Bickford, Randy (September 10, 2008). "Silver Jews' David Berman wants his new songs to be instructive". Indy Week. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Richardson, Mark (January 1, 2002). "Silver Jews". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on March 16, 2021. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ^ a b c Roberts, Randall (August 8, 2019). "David Berman, acclaimed indie-rock singer-songwriter and poet, dies at 52". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 19, 2021. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ a b c Johnson, Kjerstin (August 8, 2019). "Blue Arrangements: Remembering David Berman". The Ringer. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- ^ a b Dodero, Camille (October 24, 2007). "Provincializm #13: Silver Jew, David Berman, Part Two". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on August 20, 2021. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ Sheffield, Rob (August 8, 2019). "Remembering David Berman's Wild Kindness". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ Salmon, Peter (December 1998). "CD and Book Reviews". Texas Monthly. Archived from the original on October 9, 2021. Retrieved October 9, 2021.

- ^ Lorentzen, Christian; Taylor, Justin; Park, Ed (August 12, 2019). "David Berman (1967–2019)". Bookforum. Archived from the original on September 15, 2021. Retrieved September 15, 2021.

- ^ O'Riliey, John (December 11, 1998). "This Week's Pop CD Releases". The Guardian.

- ^ a b c d e Mason, Wyatt (October 19, 2005). "So You Want to Be a Poet, I Mean Rock Star, I Mean Poet". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 20, 2020. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- ^ a b Nichols, Travis (July 12, 2019). "Actual Air in the Purple Mountains: An Interview With David Berman by Travis Nichols". Poetry Foundation. Archived from the original on February 3, 2021. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- ^ Nachmann, Ron (November–December 2005). "Tanglewood Numbers". Tikkun. 20: 80.

- ^ Arcand, Rob (December 17, 2019). "The 10 Best Albums of 2019 | Purple Mountains Purple Mountains". Spin. Archived from the original on December 17, 2019. Retrieved October 7, 2021.

- ^ Paulson, Dave (July 20, 2008). "David Berman moves his Silver Jews further out of hiding with 'Lookout Mountain'". The Tennessean.

- ^ Martin, Richard (November 1998). "Silver Jews". CMJ New Music Report. p. 54. ISSN 1074-6978. Archived from the original on August 24, 2021. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ^ Orlov, Piotr (December 10, 2001). "Silver Jews". CMJ New Music Report. Vol. 69. p. 12. ISSN 0890-0795. Archived from the original on August 24, 2021. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ^ Oakes, Kaya (June 9, 2009). Slanted and Enchanted: The Evolution of Indie Culture. Henry Holt and Company. p. 146. ISBN 978-1-4299-3572-2.

- ^ Hockley-Smith, Sam (August 8, 2019). "David Berman was in it with the rest of us". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on August 11, 2020. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ Oakes, Kaya (June 9, 2009). Slanted and Enchanted: The Evolution of Indie Culture. Henry Holt and Company. p. 153. ISBN 978-1-4299-3572-2.

- ^ Contributors, Pitchfork (October 4, 2021). "The 200 Most Important Artists of the Last 25 Years". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on October 7, 2021. Retrieved October 7, 2021.

- ^ Earles, Andrew (2014). Gimme Indie Rock: 500 Essential American Underground Rock Albums 1981-1996. Voyageur Press. p. 284. ISBN 978-0760346488.

- ^ Grajeda, Tony (January 23, 2003). Jenkins Iii, Henry; Shattuc, Jane; McPherson, Tara (eds.). Hop on Pop: The Politics and Pleasures of Popular Culture. Duke University Press. p. 367. doi:10.1515/9780822383505. ISBN 978-0-8223-8350-5.

- ^ a b Costa, Maddy (February 22, 2002). "Watching The Detective: Maddy Costa meets the deceptively gentle David Berman - poet, singer with the Silver Jews and occasional private eye". The Guardian. Archived from the original on October 7, 2021. Retrieved October 7, 2021.

- ^ a b Rothband, Adam (August 9, 2019). "In Memoriam: David Berman". Tiny Mix Tapes. Archived from the original on December 3, 2019. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

- ^ Masters, Marc (October 6, 2021). "Myriam Gendron: Ma délire - Songs of love, lost & found". Pitchfork. Retrieved October 28, 2021.

- ^ Romney, Jonathan (December 2, 1994). "Muic: Your essential guide to new CDs - Pop". The Guardian.

- ^ a b Nichols, M. David (June 15, 2008). "Silver Jews' latest album mostly loses its way". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- ^ Marvar, Alexandra (October 10, 2008). "Just the Gist: Silver Jews' David Berman". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on October 23, 2020. Retrieved May 14, 2021.

- ^ Rosenblatt, Josh (March 9, 2007). "Perfect Liberty". Austin Chronicle. Archived from the original on September 25, 2021. Retrieved September 25, 2021.

- ^ a b Blume, Karla S. (September 7, 2006). "Silver Jews Singer Polishes Up Dirty Past". Jewish Journal. Archived from the original on June 13, 2020. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ Edwards, Mark (October 18, 1998). "On record". The Sunday Times. Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Writer, Academy of American Poets (February 20, 2014). "David Berman: Poems, Songs, and Psychedelic Soap Operas". Academy of American Poets. Archived from the original on August 11, 2020. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ^ Dolan, Jon (July 15, 2019). "Purple Mountains' Debut is a Richly Bummed-Out Comeback Album from a Brilliant Songwriter". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on August 21, 2021. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ a b Chen, Nick (August 14, 2019). "The history of the film that documented Silver Jews' earliest live shows". Dazed. Archived from the original on March 18, 2021. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

- ^ Silver, Kate (February 12, 2007). "Ber-mitzvah!". Seattle Weekly. Archived from the original on September 25, 2021. Retrieved September 25, 2021.

- ^ Hirsh, Marc (March 21, 2006). "Onstage, the Silver Jews need more luster - The Boston Globe". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on September 25, 2021. Retrieved September 25, 2021.

- ^ a b c Calvin, Aaron (April 17, 2020). "The Curious Case of the Bootleg David Berman Literary Collection". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on September 8, 2021. Retrieved September 8, 2021.

- ^ Quart, Alissa (September 12, 2019). "David Berman of Silver Jews Remembered". The New York Review of Books. Archived from the original on April 11, 2021. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

- ^ a b Paquin, Ethan A. (June 1, 2000). "Microreviews: Summer 2000 - Actual Air, David Berman". Boston Review. Archived from the original on August 22, 2021. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- ^ Somers, Erin (August 8, 2019). "David Berman, Slacker God". The Paris Review. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- ^ a b Wilson, Kathleen (December 6, 2001). "The Gift of Travel". The Stranger. Retrieved October 28, 2021.

- ^ Clark, Chad; Toth, James (August 10, 2019). "Silver Jews' David Berman Remembered By His Peers, In His Own Words". NPR. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

- ^ a b Ward, David C. (2000). "The boy's a bit clever". PN Review. 26 (4). Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- ^ a b c Christophersen, Bill (2000). "Classical virtues--and vices". Poetry. 177. Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- ^ a b Nelson, Chris (October 30, 1999). "Silver Jews Leader Delivers Poetic Contradictions With 'Actual Air'". MTV News. Archived from the original on August 24, 2021. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ^ a b Timberg, Scott (March 24, 2004). "The Delphic oracle of indie rock: a Nashville poet". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 23, 2021.

- ^ a b Roberts, Randall (August 1999). "Actual Air". CMJ New Music Report. ISSN 1074-6978. Archived from the original on August 24, 2021. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ^ Hunter, James (September 16, 1999). "Rocklit". Rolling Stone.

- ^ Billet, Alexander (August 21, 2021). "David Berman and the Re-Enchantment of Life". Jacobin. Archived from the original on August 20, 2021. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ Elaine, Blair (2000). "The fantastic journal". The Village Voice. Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- ^ Contributors, Believer (February 5, 2020). ""Final Words Are So Hard to Devise"". Believer. Archived from the original on August 20, 2021. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ Smith, Rich (August 8, 2019). "David Berman Is Dead". The Stranger. Archived from the original on August 22, 2021. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- ^ Baker, Emily (October 3, 2019). "19 renowned lyricists who also do 'proper' poetry". NME. Archived from the original on August 27, 2021. Retrieved August 27, 2021.

- ^ Best, Sophie (November 4, 2005). "Tanglewood Numbers". The Age.

- ^ Writer, Nashville Scene (August 15, 2017). "Friends and Bandmates Reflect on the Life of David Berman". Nashville Scene. Archived from the original on August 18, 2021. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ a b Howe, Brian (July 16, 2019). "David Berman's 'Purple Mountains' Is a Welcome Return From an Old Master". Spin. Archived from the original on October 30, 2020. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ D’Souza, Nandini (November 1, 2005). "The Chosen One". Women's Wear Daily.

- ^ Marx, Jonathan (March 9, 2008). "Poet, musician David Berman reflects on his writing life". The Tennessean.

- ^ Simpson, Dave (November 22, 1999). "Arts: Paperback writers: It keeps Michael Stipe up at night and gives Bono a break from the day job. But Nick Cave got it out of his system years ago. Dave Simpson on pop's love affair with the novel". The Guardian.

- ^ Wilson, Carl (September 2, 2008). "The picaresque poet". The Globe & Mail.

- ^ Evans, Clarie (July 1, 2008). "Lookout Mountain, Lookout Sea". Bitch. 40.

- ^ Riesman, Abraham (August 8, 2019). "David Berman Struggled to Feel the Joy He Brought Us". Vulture. Archived from the original on April 17, 2021. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

- ^ Guzmán, Rafer (March 21, 2006). "After dark skies, poet finds a silver lining". Newsday.

- ^ Brinn, David (August 8, 2019). "David Berman, Silver Jews' founder, dead at 52". The Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on August 24, 2021. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ^ Sullivan, Matt (April 11, 2021). "Through Lines: Albums Highlighting Nashville's 2000s Underground Explosion | Silver Jews, Tanglewood Numbers". Nashville Scene. Archived from the original on August 19, 2021. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ Clark, Eric (October 9, 2008). "Silver Jews on 'Lookout' for a wider audience". The Gazette. Archived from the original on September 12, 2021. Retrieved September 12, 2021.

- ^ Drozdowski, Ted (March 23, 1995). "Sebadoh: Low-Fi Romantics". Rolling Stone.

- ^ Richardson, Mark (August 8, 2019). "David Berman Changed the Way So Many of Us See the World". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on January 28, 2021. Retrieved September 8, 2021.

- ^ Tully Claymore, Gabriela (December 3, 2019). "The 50 Best Albums Of 2019 | Purple Mountains – Purple Mountains (Drag City)". Stereogum. Archived from the original on October 7, 2021. Retrieved October 7, 2021.

- ^ Snapes, Laua (December 20, 2019). "The 50 best albums of 2019: the full list | Purple Mountains – Purple Mountains". The Guardian. Archived from the original on October 6, 2021. Retrieved October 7, 2021.

- ^ DeVille, Chris (November 4, 2019). "The 100 Best Albums Of The 2010s | Purple Mountains – Purple Mountains (Drag City, 2019)". Stereogum. Archived from the original on October 7, 2021. Retrieved October 7, 2021.

Sources[]

- Academy of American Poets Writer (February 20, 2014). "David Berman: Poems, Songs, and Psychedelic Soap Operas". Academy of American Poets. Archived from the original on August 11, 2020. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- Albertson, Jasmine (July 15, 2021). "John Vanderslice Breaks Down His Dark and Feverish Tribute EP to David Berman (KEXP Track-By-Track)". KEXP. Archived from the original on July 15, 2021. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- Angel, Arielle; Goldman, Nathan (August 9, 2019). "Kaddish for David Berman". Jewish Currents. Archived from the original on December 15, 2020. Retrieved April 7, 2021.