Doffer

A doffer is someone who removes ("doffs") bobbins, pirns or spindles holding spun fiber such as cotton or wool from a spinning frame and replaces them with empty ones. Historically, spinners, doffers, and sweepers each had separate tasks that were required in the manufacture of spun textiles. From the early days of the industrial revolution, this work, which requires speed and dexterity rather than strength, was often done by children.[1] After World War I, the practice of employing children declined, ending in the United States in 1933.[2] In modern textile mills, doffing machines have now replaced humans.[3]

The 19th century[]

The Industrial Revolution created growing demand for child labor in the mills and factories, since children were easier to supervise than adults and good at monotonous, repetitive tasks that often required little physical strength, but where small bodies and nimble fingers were an advantage.[4]

Children were employed in the mills as spinners, sweepers and doffers, with girls usually starting as spinners and boys as doffers and sweepers. When the bobbins on the spinning frames were full, the machinery stopped. The doffers would swarm into the mill and, as quickly as possible, change all the bobbins, after which the machinery would be restarted and the doffers were free to amuse themselves until the next change-over. On the newer and taller frames, the doffers often had to climb to reach the bobbins.[5]

Great Britain[]

In Lancashire the doffing boys were free to do what they liked once they had completed a doffing, as long as they stayed within earshot of the "throstle jobber," who would whistle when they were next needed. They were motivated to do the work as fast as possible, since this gave them as long as possible to play. Between ten and twelve boys could handle a factory with about ten thousand throstle spindles, depending on the amount of yarn being spun.[6] The doffers were usually the sons of poor people, and were small and skinny. They were sometimes called "The Devil's Own" for the tricks that they would get up to.[7] As a rule they would go barefoot except at the coldest times of year.[8]

At Quarry Bank Mill in Styal, England, near Manchester, a doffer earned 1s/6d a day in 1790, and by 1831 was earning from 2s. to 3s. a day. An overlooker's wage in the same period rose from 15s. to 17s.[9] In Leeds in the 1830s a doffer could earn 4s. to 5s.[10] In the textile industry in Britain, wages for children continued to rise steadily compared to those for adults during the period from 1830 to 1860, indicating that demand was outstripping supply.[4] In Belfast linen factories in 1890 girls were employed as doffers, earning the equivalent of US $1.43 daily (about 6s. at the time.)[a][12]

North America[]

In the United States in the first part of the 19th century, although the day was long, the doffers only worked for about four hours each day.[5] Memoirs from writers such as Lucy Larcom and Harriet Hanson Robinson describe the long hours, but also the leisurely pace of work and the opportunities for social interactions.[1] In Massachusetts in 1830 a doffer boy earned 25 cents a day. An overseer of rooms would make $1.25 a day, and the superintendent of a mill earned $2.00 a day, considered an excellent wage at the time.[13] In the southern cotton mills it was customary to employ only whites for most jobs in the mill, although blacks had outside jobs and some inside jobs such as firing the boilers. This persisted well into the 20th century.[14]

During the later part of the 19th century, working conditions in the U.S. textile industry deteriorated. Immigrant textile workers coming from Yorkshire and Lancashire to New England found the mills poorly run, with the managers cheating on measurements of cuts of cloth and time worked, and arbitrarily cutting wages without warning. These workers were often skilled, accustomed to being well-treated in their home country, and accustomed to taking industrial action if they were not.[15] There were a series of strikes from the 1870s onward.[16]

An 1889 Royal Commission of Inquiry into the Relations of Capital and Labor in Canada recorded a statement by the assistant superintendent of St. Croix Cotton Mills in St. Stephen, New Brunswick. He said the mill employed some young boys around fifteen years old as doffers, but the average doffer was aged thirty. Wages were from 65 to 80 cents a day. In the summer hours were from 6:30 am to 6 pm, with a half day on Saturday. Winter hours were slightly longer.[17] An employee who had worked in both countries reported that wages were better than in the United States and working conditions better, although the hours were about the same.[18]

Doffers in 1887 in a large mill in Cabarrus County, North Carolina, both boys and girls, earned 40 cents a day.[19] In New England in the 1890s, the doffers, piecers and back boys had their own union, and were not admitted to the mule spinners' union, even though they often aspired to become mule spinners.[20] Many left the industry rather than tolerate the conditions.[21] William Madison Wood, the manager at the Washington Mill in Lawrence, Massachusetts, instituted a system in 1895 where employees gained bonuses for meeting production quotas, as long as they missed no more than one day per month. The effect was that weavers drove spinners to produce, spinners drove doffers and so on, and that workers came in even when sick or injured. Wood then used the increased pay to justify running the looms at ever faster speeds.[22]

Rags to riches[]

A doffer could achieve success if he had enough energy and ability. Stephen Davol, born in November 1807, joined his elder brothers as a doffer in the Troy mill in Fall River, Massachusetts in 1818. After rising through the ranks, in 1833 he became superintendent of the Pocasset Mill at the age of twenty-six. He drew up the plans for building a giant new mill for the Pocasset company, 219 feet (67 m) by 75 feet (23 m) and rising to five stories. The mill was unusual for its time in being built as a whole to plans that considered both the structure and the arrangement of the machinery, belts and gearing. From 1842 to 1860 Davol was agent, or chief executive, of the Troy Mill. By the 1870s he was a member of the board of ten different companies.[23]

George Alexander Gray (1851–1912) is another example. Gray started work as a doffer before the Civil War when aged eight, earning ten cents a day in a mill at Pinhook, North Carolina. He had little education, but rose to the position of overseer in the mill, and then was given the job of supervising installation of machinery in new plants. He moved to Gastonia, North Carolina, where he built the first mill with his own capital. By the time he died, there were eleven mills in Gastonia, of which Gray had been involved in establishing nine.[24] Carl Augustus Rudisill (1884–1979) began work as a doffer boy in Cherryville, North Carolina, at ten cents a day. He was superintendent of the Indian Creek Manufacturing Company by 1907, and later developed the Carlton Yarn Mills into a major operation. He was a member of the North Carolina legislature from 1937 to 1941.[25]

Early 20th century[]

Netherlands[]

Towards the end of the 19th century, doffers in the Netherlands were mostly boys of about 12 years of age, who in 1890 had to go to school for a few hours each day. They were part of a team headed by a "minder", who was responsible for running two mules, and including a "big piecer" and a "little piecer", whose main job was to rejoin broken threads.[26] Around 1916, self-acting mules were introduced from Germany, which were simpler to operate. The team was reduced to one spinner and one piecer, with the position of doffer eliminated. The pace of modernization and mechanization was faster than in Lancashire, where the unions were more powerful.[27]

India[]

A report on conditions in the Bombay mills in India between 1891 and 1917 noted that laws had been passed in response to agitation in England by which no child under nine years old could be employed. In theory, children under fourteen could not work more than seven hours per day, broken into two work periods with a long rest period in between. In practice, much younger children were working longer hours at jobs such as doffing.[28] A man working in the mills would be paid Rs.7 to Rs.9 for the least skilled jobs to as much as Rs18 to Rs22 on a piece-work basis for a mule's minder or spinner. Doffer boys working full-time would earn Rs.4 to Rs.6.[29] As of 1912 about 4,000 boys and girls were employed in the Indian mills, each doffing about 350 ring spindles.[30]

United States[]

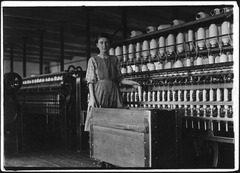

A regular worker (doffer) in Richmond Spinning Mills. Photo during working hours. Chattanooga, Tenn. Lewis Hine 1910

Adrienne Pagnette, illiterate adolescent French girl. Winchendon, Mass. Lewis Hine 1911

Spinners and doffers in Lancaster Cotton Mills, Lewis Hine 1908

By 1900 in Crown Mills, Whitfield County, Georgia, the average doffer was fourteen years old.[31] A doffer in North Carolina in 1904 would earn $2.40 per week, while a head doffer would earn $3.50. Skilled workers would earn more. A drawing-in girl could make $6.00, a warper $7.50 and an engineer up to $9.00, while the weave boss made as much as $15.00.[32] The working week would be ten hours a day from Monday to Saturday.[33] In 1907, a doffer in North Carolina only had to work about half the time, being able to play baseball, swim in the local river or otherwise relax until the whistle of the head doffer called them back to the mill. If a rural mill depended on a water wheel for power, a drought could provide more free time as the mill would only run a few hours each day.[34]

Lewis Hine obtained a job with the National Child Labor Committee in the United States in 1908, and over the next decade took many photographs that documented children at work.[35] Many of the children worked barefoot, which made it easier to climb the machinery to reach bobbins or broken threads. Children met with accidents more often than adults. Hine was told by the overseer of one mill "We don't have any accidents in this mill .... Once in a while a finger is mashed, or a foot, but it don't amount to anything." Conditions were demanding. There was a constant racket of machinery. The mill windows were kept closed, creating a hot and humid atmosphere in which cotton threads were less likely to break. The air was filled with lint and dust, making breathing difficult, and often leading to diseases such as tuberculosis and chronic bronchitis.[36] Some workers suffered from Byssinosis, or brown lung, caused by prolonged exposure to cotton dust.[37]

At that time boys might start to work as doffers before the age of seven.[36] However, as Hine reported, "In every case, the youngsters told me their age as 12 years, even to the little Hop-o'-My-Thumb, whom the others dubbed 'our baby doffer.' They would hesitate when I asked them, but always succeeded in remembering that they were twelve."[38] A photograph by Hine of an evidently very young doffer at the Melville Manufacturing Company in Cherryville, North Carolina appeared on the cover of a National Child Labor Committee report around 1912.[39] Hine's photographs of child workers such as doffers were influential in driving reform of child employment laws in the United States, an early example of the power of photo journalism.[40] New laws were introduced, so that by 1914 very few children under 12 were working in the mills, and most were over 14.[41]

Sweeper and doffer boys in Lancaster Cotton Mills. Lewis Hine 1908

Doffers in Cherryville Mfg. Co., N.C. Lewis Hine 1909

A doffer in Lincolnton Mill. Lincolnton, N.C. Lewis Hine 1908

Post World War I[]

After World War I ended in 1918, the US textile industry was left with surplus capacity and went into a slump, not recovering until after the 1930s Great Depression. In response, mill owners cut wages and laid off workers, or put them on short hours, while mechanizing further to improve efficiency. New laws made child labor more expensive, and children could not handle the new machinery. The practice of using child labor in the mills declined, finally ending completely when the NIRA was adopted in 1933.[2] Changes to the Factories Act in 1922 reduced formal child labor in the textile factories in India. By the 1940s there were negligible numbers of children in the Kanpur mills. Most of the remaining child workers were doffer boys.[42] Elsewhere the change was slower. In Kenya in 1967 "doffer boy" was still listed as a job position in the Kisumu Cotton Mills, one of the lowest paid.[43]

Improvements in working conditions were gradually introduced. In 1940 the British recognized byssinosis, or brown lung disease, and started to compensate victims. Due to lack of research and industry resistance, nothing was done about the disease in the United States until the 1970s.[37] Activists organized brown lung screening clinics in Piedmont in 1975.[44] The Carolina Brown Lung Association had 7,000 members by 1981. In 1984 the Occupational Health and Safety Administration responded to pressure from this group and implemented a new cotton dust standard.[45]

In modern mills the doffing process is relatively automated. with a mechanical doffer fitted to the winder that cuts and aspirates the yarn, removes the packages and places them in a yarn buggy, fits the empty tubes and transfers the yarn so winding can continue.[3]

High Point, North Carolina. Pickett Yarn Mill. Doffer in action.

Pickett Yarn Mill. Speeder - doffer putting up ends - highly skilled. 1937

Pickett Yarn Mill. Frame hand doffing spools off speeder - highly skilled. 1937

Mount Holyoke, Massachusetts - Silk. William Skinner and Sons. Doffing 1936 - 1937

Poems and songs[]

The song "The Doffing Mistress" is about flax spinning in Northern Ireland and describes the doffers respect for their mistress. The line "she hangs her coat on the highest pin" is because the doffer's work could lead to deformity of the spine.[46]

Edwin Waugh is the author of the dialect poem "The Little Doffer" about a doffer in a Lancashire mill who obtained work despite his unsatisfactory replies to the overlooker (foreman).[47]

See also[]

- Spinning mule

- Ring spinning

- Carmela Teoli, a doffer who testified before the U.S. Congress about being scalped by a machine

References[]

- ^ In the 1890s the exchange rate varied very little from the "par" rate of $4.8665 to £1. There were twenty shillings to the pound. So $1.43 = (1.43/4.8665)*20s. = 5.88 s. The doffer's daily wage would be worth perhaps $35 or £22 in 2011, although people now buy a very different mix of goods and services, e.g. phone calls but not coal.[11]

- ^ a b Zonderman 1992, p. 27.

- ^ a b Hindman 2009, p. 183-185.

- ^ a b Fourné 1999, p. 596.

- ^ a b Hindman 2009, p. 58-59.

- ^ a b Hindman 2009, p. 474.

- ^ Newbigging 1891, p. 50.

- ^ Newbigging 1891, p. 51.

- ^ Newbigging 1891, p. 52.

- ^ Collier 1965, p. 41-42.

- ^ Morris 1990, p. 102.

- ^ Nye 2011.

- ^ US Bureau of Foreign Commerce 1891, p. 117.

- ^ Earl 1877, p. 28.

- ^ Rhyne 1930, p. 47-48.

- ^ Blewett 2000, pp. 190–191.

- ^ Blewett 2000, p. 398.

- ^ Armstrong & Freed 1889, p. 481.

- ^ Armstrong & Freed 1889, p. 486.

- ^ Vivian 1891, p. 394.

- ^ Blewett 2000, p. 372.

- ^ Blewett 2000, p. 389.

- ^ Watson 2006, p. 23.

- ^ Earl 1877, p. 56-57.

- ^ Mitchell 1921, p. 109.

- ^ Wehunt-Black 2008, p. 105.

- ^ Groot 1995, p. 57.

- ^ Groot 1995, p. 59.

- ^ Punekar & Varickayil 1990, p. 76.

- ^ Punekar & Varickayil 1990, p. 258.

- ^ Punekar & Varickayil 1990, p. 16-17.

- ^ Flamming 1995, p. 99.

- ^ Hall & Korstad 2000, p. 79.

- ^ Hall & Korstad 2000, p. 78.

- ^ Hall & Korstad 2000, p. 88.

- ^ Freedman 1998, p. 19.

- ^ a b Freedman 1998, p. 35.

- ^ a b Hall & Korstad 2000, p. 81.

- ^ Hindman 2009, p. 168.

- ^ Wehunt-Black 2009, p. 20.

- ^ Naef 2004, p. 84.

- ^ Hindman 2009, p. 177-178.

- ^ Joshi 2005, p. 87.

- ^ Kenya Gazette 1967, p. 1045.

- ^ Hall & Korstad 2000, p. 358.

- ^ Hall & Korstad 2000, p. 360.

- ^ Raven, Jon (1978) Victoria's Inferno. Tettenhall: Broadside ISBN 0-9503722-3-4; p. 139

- ^ Hollingworth, Brian, ed. (1977) Songs of the People. Manchester University Press ISBN 0-7190-0612-0; pp. 18, 130

| Look up doffer in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Doffers. |

Sources[]

- Armstrong, James; Freed, Augustus Toplady (1889). Report of the Royal commission on the relations of labor and capital in Canada. Printed for the queen's printer, A. Senecal. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

- Blewett, Mary H. (2000). Constant Turmoil: The Politics of Industrial Life in Nineteenth-Century New England. University of Massachusetts Press. p. 372. ISBN 978-1-55849-239-4. Retrieved 2012-06-30.

- Collier, Frances (1965). The Family Economy of the Working Classes in the Cotton Industry, 1784–1833. Manchester University Press ND. GGKEY:B5CJGLHCHZ0. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

- Earl, Henry Hilliard (1877). A centennial history of Fall River, Mass: comprising a record of its corporate progress from 1656 to 1876, with sketches of its manufacturing industries, local and general characteristics, valuable statistical tables, etc. Atlantic Pub. and Engraving Co. p. 28. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

- Flamming, Douglas (1995-11-20). Creating the Modern South: Millhands and Managers in Dalton, Georgia, 1884–1984. Univ of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-4545-5. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

- Fourné, Franz (1999-11-01). Synthetic Fibers: Machines and Equipment, Manufacture, Properties : Handbook for Plant Engineering, Machine Design, and Operation. Hanser Verlag. ISBN 978-1-56990-250-9. Retrieved 2012-06-29.

- Freedman, Russell (1998-03-23). Kids at Work: Lewis Hine and the Crusade Against Child Labor. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-395-79726-6. Retrieved 2012-06-30.

- Groot, Gertjan De (1995-03-01). Women Workers and Technological Change in Europe in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-7484-0260-1. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

- Hall, Jacquelyn Dowd; Korstad, Robert (2000). Like a Family: The Making of a Southern Cotton Mill World. UNC Press Books. ISBN 978-0-8078-4879-1. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

- Hindman, Hugh D. (2009-09-30). The World of Child Labor: An Historical and Regional Survey. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-1707-1. Retrieved 2012-06-30.

- Joshi, Chitra (2005-03-05). Lost Worlds: Indian Labour and Its Forgotten Histories. Anthem Press. ISBN 978-1-84331-128-7. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

- Kenya Gazette. 1967-09-29. Retrieved 2012-06-30.

- Mitchell, Broadus (1921). The Rise of Cotton Mills in the South. Univ of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-57003-421-3. Retrieved 2012-06-30.

- Morris, Robert John (1990). Class, Sect, and Party: The Making of the British Middle Class : Leeds, 1820–1850. Manchester University Press ND. ISBN 978-0-7190-2225-8. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

- Naef, Weston J. (2004-04-15). Photographers of Genius at the Getty. Getty Publications. ISBN 978-0-89236-749-8. Retrieved 2012-06-30.

- Newbigging, Thomas (1891). "Lancashire Factory Doffers". Lancashire characters and places. Brook & Chrystal. p. 52. Retrieved 2012-06-30.

- Nye, Eric W. (2011). "A Method for Determining Historical Monetary Values". University of Wyoming. Archived from the original on 2012-05-04. Retrieved 2012-07-04.

- Punekar, S.D.; Varickayil, R. (1990). Labour Movement in India: Documents 1891–1917. Popular Prakashan. ISBN 978-81-7154-331-1. Retrieved 2012-06-30.

- Rhyne, Jennings Jefferson (1930). Some Southern Cotton Mill Workers and Their Villages. Ayer Publishing. ISBN 978-0-405-10195-3. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

- US Bureau of Foreign Commerce (1891). Reports from the consuls of the United States. G.P.O. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

- Vivian, Thomas Jondrie (1891). The commercial, industrial, agricultural, transportation and other interests of California: being a report on that state for 1890 made to S.G. Brock, chief of the Bureau of Statistics, Treasury Department. Govt. print. off. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

- Watson, Bruce (2006-07-25). Bread and Roses: Mills, Migrants, and the Struggle for the American Dream. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-303735-4. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

- Wehunt-Black, Rita (2008-03-15). Gaston County, North Carolina: A Brief History. The History Press. ISBN 978-1-59629-327-4. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

- Wehunt-Black, Rita (2009-03-16). Cherryville. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-6855-3. Retrieved 2012-06-30.

- Zonderman, David A. (1992-01-02). Aspirations and Anxieties: New England Workers and the Mechanized Factory System, 1815–1850. Oxford University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-19-505747-8. Retrieved 2012-06-28.

- Industrial occupations

- Obsolete occupations

- Textile industry

- Labor history

- 19th century in the United Kingdom

- Child labour