Dookie

| Dookie | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by Green Day | ||||

| Released | February 1, 1994 | |||

| Recorded | August–October 1993 | |||

| Studio | Fantasy, Berkeley, California | |||

| Genre |

| |||

| Length | 39:34 | |||

| Label | Reprise | |||

| Producer |

| |||

| Green Day chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Dookie | ||||

| ||||

Dookie is the third studio album and the major label debut by American rock band Green Day, released on February 1, 1994 by Reprise Records. The band's first collaboration with producer Rob Cavallo, it was recorded in late 1993 at Fantasy Studios in Berkeley, California. Written mostly by frontman Billie Joe Armstrong, the album is heavily based around his personal experiences, with themes such as boredom, anxiety, relationships, and sexuality. The album was promoted with five singles: "Longview", "Basket Case", a re-recorded version of "Welcome to Paradise" (originally on their Kerplunk album), "When I Come Around", and the radio-only "She". "All by Myself" is a hidden track performed by drummer Tré Cool.

Dookie received critical acclaim upon its release, and won the band a Grammy Award for Best Alternative Album in 1995. It was also a worldwide success, reaching number two in the United States and the top five in several other countries; it is credited with bringing punk rock to mainstream popularity, and propelling Green Day to worldwide fame. It was later certified diamond by the RIAA, and has sold close to 20 million copies worldwide,[1] making it the band's best-selling album and one of the best-selling albums worldwide. In 2003, Rolling Stone placed Dookie at number 193 on their list of the "500 Greatest Albums of All Time", maintaining the rating in a 2012 revised list. In 2020, Rolling Stone re-ranked the album at number 375 on another revised list.[2]

Background and recording[]

Following the underground success of the band's second studio album Kerplunk (1991), a number of major record labels became interested in Green Day.[3] Representatives of these labels attempted to entice the band to sign by inviting them for meals to discuss a deal, with one manager even inviting the group to Disneyland.[4] The band declined these advances until meeting producer and Reprise representative Rob Cavallo. They were impressed by his work with fellow Californian band The Muffs, and later remarked that Cavallo "was the only person we could really talk to and connect with".[4]

Eventually, the band left their independent record label, Lookout! Records, on friendly terms and signed to Reprise. Signing to a major label caused many of the band's original fans from the independent music club 924 Gilman Street to regard Green Day as sell-outs.[5][6] The club banned Green Day from entering since the major label signing.[4][7] Reflecting back on the period, lead vocalist Billie Joe Armstrong told Spin magazine in 1999, "I couldn't go back to the punk scene, whether we were the biggest success in the world or the biggest failure [...] The only thing I could do was get on my bike and go forward."[8] The group later returned in 2015 to play a benefit concert.[9]

Cavallo was chosen as the main producer of the album, with Jerry Finn as the mixer. Green Day originally gave the first demo tape to Cavallo, and after listening to it during the car ride home he sensed that "[he] had stumbled on something big."[3] The band's recording session lasted three weeks and the album was mixed twice.[4] Armstrong claimed that the band wanted to create a dry sound, "similar to the Sex Pistols' album or first Black Sabbath albums."[10] The band felt the original mix to be unsatisfactory. Cavallo agreed, and it was remixed at Fantasy Studios in Berkeley, California.[10] Armstrong later said of their studio experience, "Everything was already written, all we had to do was play it."[4][10]

Writing and composition[]

Much of the album's content was written by Armstrong, except "Emenius Sleepus" written by bassist Mike Dirnt, and the hidden track, "All by Myself", which was written by drummer Tré Cool. The album touched upon various experiences of the band members and included subjects like anxiety and panic attacks, masturbation, sexual orientation, boredom, mass murder, divorce, and ex-girlfriends.[4]

Songs 1–7[]

Armstrong wrote the song "Having a Blast" when he was in Cleveland in June 1992.[11] The single "Longview" had a signature bass line that bassist Dirnt wrote while under the influence of LSD.[12] "Welcome to Paradise", the second single from Dookie, was originally on the band's second studio album, Kerplunk. The song was re-recorded with a less grainy sound for Dookie.[3] The song never had an official music video; however, a certain live performance of the song is often associated as a music video. The video is located on Green Day's official website.[13]

The hit single "Basket Case", which appeared on many singles charts worldwide,[14][15] was also inspired by Armstrong's personal experiences. The song deals with Armstrong's anxiety attacks and feelings of "going crazy" prior to being diagnosed with a panic disorder.[10] In the third verse, "Basket Case" references soliciting a male prostitute; Armstrong noted that "I wanted to challenge myself and whoever the listener might be. It's also looking at the world and saying, 'It's not as black and white as you think. This isn't your grandfather's prostitute – or maybe it was.' "[16] The music video was filmed in an abandoned mental institution. It is one of the band's most popular songs.[17]

Songs 8–14[]

The radio-only single "She" was written by Armstrong about a former girlfriend who showed him a feminist poem with an identical title.[10] In return, Armstrong wrote the lyrics of "She" and showed them to her.[10] She later moved to Ecuador, prompting Armstrong to put "She" on the album. The same ex-girlfriend is also the topic of the songs "Sassafras Roots" and "Chump".[10]

The final single, "When I Come Around", was again inspired by a woman, though this time being about Armstrong's wife, then former girlfriend, Adrienne. Following a dispute between the couple, Armstrong left Adrienne to spend some time alone.[3] The video featured the three band members walking around Berkeley and San Francisco at night, eventually ending up back at the original location. Future touring member of Green Day, Jason White, made a cameo in the video with his then-girlfriend.[4] The song was the band's first top ten single at number 6 on the Hot 100 Airplay chart and stayed number 1 on the Modern Rock Tracks chart for 7 weeks (2 weeks longer than "Basket Case"). It also hit number 2 on both the Mainstream Rock Tracks and the Mainstream Top 40 charts. The song "Coming Clean" deals with Armstrong's coming to terms with his bisexuality when he was 16 and 17 years old.[18] In his interview with The Advocate magazine, he stated that although he has never had a relationship with a man, his sexuality has been "something that comes up as a struggle in me". Armstrong wrote the song "In the End" about his mother and her husband. He is quoted saying: "That song is about my mother's husband, it's not really about a girl, or like anyone directly related to me in a relationship. In the End's about my mother."[19]

Hidden track, "All By Myself", with vocals and guitar by drummer Tre Cool, plays 1 minute and 17 seconds after "F.O.D." ends.

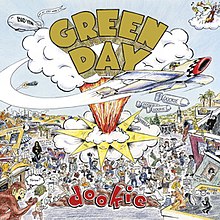

Packaging[]

The name of the album is a reference to the band members often suffering from diarrhea, which they referred to as "liquid dookie", as a result of eating spoiled food while on tour. Initially the band was to name the album Liquid Dookie; however, this was deemed "too gross", and so they settled on the name Dookie.[4][10]

The album artwork by fellow East Bay punk Richie Bucher caused controversy, since it depicted bombs being dropped on people and buildings. The setting is a replica of Berkeley's Telegraph Avenue. In the center, there is an explosion, with the band's name at the top.[20] Armstrong has since explained the meaning of the artwork:

I wanted the art work to look really different. I wanted it to represent the East Bay and where we come from, because there's a lot of artists in the East Bay scene that are just as important as the music. So we talked to Richie Bucher. He did a 7-inch cover for this band called Raooul that I really liked. He's also been playing in bands in the East Bay for years. There's pieces of us buried on the album cover. There's one guy with his camera up in the air taking a picture with a beard. He took pictures of bands every weekend at Gilman's. The robed character that looks like the Mona Lisa is the woman on the cover of the first Black Sabbath album. AC/DC guitarist Angus Young is in there somewhere too. The graffiti reading "Twisted Dog Sisters" refers to these two girls from Berkeley. I think the guy saying "The fritter, fat boy" was a reference to a local cop.[21]

The back cover on early prints of the CD featured a plush toy of Ernie from Sesame Street, which was airbrushed out of later prints for fear of litigation; however, Canadian and European prints still feature Ernie on the back cover.[4] Some rumors suggest that it was removed because it led parents to think that Dookie was a child's lullaby album or that the creators of Sesame Street had sued Green Day.[3]

Release[]

Dookie was released on February 1, 1994.[22] The album only sold 9,000 copies in its first week[23] and didn't gain commercial success until the summer of 1994. Dookie charted in seven countries, peaking at number two on the Billboard 200 in the United States,[5] and was a success in several other countries, peaking as high as number one in New Zealand;[24] the lowest peak in any country was in the United Kingdom at number 13.[15] While all the singles from the album charted in a few countries, the hit single "Basket Case" entered the top 10 in the United Kingdom and Sweden. Later in 1995, the album received a Grammy Award for Best Alternative Music Album, with "Longview" and "Basket Case" each being nominated for a Grammy.

Throughout the 1990s, Dookie continued to sell well, eventually receiving diamond certification[25] in 1999; by 2013, Dookie had sold over 20 million copies worldwide and remains the band's best-selling album.[26]

Reception[]

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Alternative Press | |

| Billboard | |

| Chicago Sun-Times | |

| Chicago Tribune | |

| NME | 7/10[31] |

| Pitchfork | 8.7/10[32] |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| Spin Alternative Record Guide | 8/10[34] |

| The Village Voice | A−[35] |

Dookie was released to critical acclaim. Bill Lamb at About.com regards it as an album that only gets better with time, calling it "one of the landmark albums of the 1990s".[36] Stephen Thomas Erlewine of AllMusic described Dookie as "a stellar piece of modern punk that many tried to emulate but nobody bettered".[22] In 1994, Time claimed Dookie as the third best album of the year, and the best rock album of 1994.[37] Jon Pareles from The New York Times, in early 1995, described the sound of Dookie as, "Punk turns into pop in fast, funny, catchy, high-powered songs about whining and channel-surfing; apathy has rarely sounded so passionate."[38] Rolling Stone's Paul Evans described Green Day as "convincing mainly because they've got punk's snotty anti-values down cold: blame, self-pity, arrogant self-hatred, humor, narcissism, fun".[39]

Neil Strauss of The New York Times, while complimentary of the album's overall quality, noted that Dookie's pop sound only remotely resembled punk music.[40] The band did not respond initially to these comments, but later claimed that they were "just trying to be themselves" and that "it's our band, we can do whatever we want".[4] Dirnt claimed that the follow-up album, Insomniac, one of the band's hardest albums lyrically and musically, was the band releasing their anger at all the criticism from critics and former fans.[4]

Along with The Offspring's Smash,[41][42] Dookie has been credited for helping bring punk rock back into mainstream music culture.[43] Thomas Nassiff at Fuse cited it as the most important pop-punk album.[44]

In April 2014, Rolling Stone placed the album at No. 1 on its "1994: The 40 Best Records From Mainstream Alternative's Greatest Year" list.[45] A month later, Loudwire placed Dookie at No. 1 on its "10 Best Hard Rock Albums of 1994" list.[46] Guitar World ranked Dookie at number thirteen in their list "Superunknown: 50 Iconic Albums That Defined 1994".[47]

Accolades[]

Since its release, Dookie has been featured heavily in various "must have" lists compiled by the music media. Some of the more prominent of these lists to feature Dookie are shown below; this information is adapted from Acclaimed Music.[48]

| Publication | Country | Accolade | Year | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kerrang! | United Kingdom | The Kerrang! 100 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die[49] | 1998 | 33 |

| Classic Rock & Metal Hammer | The 200 Greatest Albums of the 90s[50] | 2006 | N/A | |

| Robert Dimery | United States | 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die[51] | 2005 | N/A |

| Rolling Stone | The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time[52][2] | 2020 | 375 | |

| Best Albums of 1994 (Readers Choice)[53] | 1994 | 1 | ||

| 1994: The 40 Best Records From Mainstream Alternative's Greatest Year[45] | 2014 | |||

| Loudwire | 10 Best Hard Rock Albums of 1994[46] | |||

| Rolling Stone | 100 Best Albums of the Nineties[54] | 2010 | 30 | |

| Spin | 100 Greatest Albums, 1985–2005[55] | 2005 | 44 | |

| Rock and Roll Hall of Fame | The Definitive 200[56] | 50 | ||

| Kerrang! | United Kingdom | 51 Greatest Pop Punk Albums Ever[57] | 2015 | 2 |

Live performances[]

Immediately following the release of Dookie, the band embarked on an international tour, beginning in the United States, for which they used a bookmobile belonging to Tré Cool's father to travel between shows.[4] An audience of millions saw Green Day's performance at Woodstock '94 on Pay-per-view, helping the band attract more fans. This event was the location of the infamous[58] mud "fight" between the band and the crowd, which continued beyond the end of Green Day's set.[59] During the fight, Dirnt was mistaken for a fan by a security guard, who tackled him and then threw him against a monitor, causing him to injure his arm and break two of his teeth.[60]

The band also appeared at Lollapalooza and the Z100 Acoustic Christmas at Madison Square Garden, where Armstrong performed the song "She" entirely naked due to him not knowing if they'll ever perform there again.[7][61] Having toured throughout the United States and Canada, the band played a few shows in Europe before beginning the recording sessions for the subsequent album, Insomniac. During the tour, Armstrong was quite homesick. His wife, Adrienne Armstrong, whom he had married shortly after the release of Dookie, was pregnant during most of the tour, and Armstrong was upset about being unable to help and care for her.[4]

In 2013, Dookie was played in its entirety at select European dates as a celebration of the album's upcoming 20th anniversary.[26][62]

Track listing[]

All lyrics written by Billie Joe Armstrong, except where noted; all music composed by Green Day.[63]

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Burnout" | 2:07 |

| 2. | "Having a Blast" | 2:44 |

| 3. | "Chump" | 2:53 |

| 4. | "Longview" | 3:59 |

| 5. | "Welcome to Paradise" (new recording) | 3:44 |

| 6. | "Pulling Teeth" | 2:30 |

| 7. | "Basket Case" | 3:02 |

| 8. | "She" | 2:13 |

| 9. | "Sassafras Roots" | 2:37 |

| 10. | "When I Come Around" | 2:57 |

| 11. | "Coming Clean" | 1:34 |

| 12. | "Emenius Sleepus" (Mike Dirnt) | 1:43 |

| 13. | "In the End" | 1:46 |

| 14. | "F.O.D." (song ends at 2:52, followed by hidden track "All by Myself" written and performed by Tré Cool, which starts at 4:09) | 5:46 |

| Total length: | 39:34 | |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 14. | "F.O.D." | 2:50 |

| 15. | "All by Myself" (written and performed by Tré Cool) | 1:40 |

| Total length: | 38:22 | |

Personnel[]

Green Day

- Billie Joe Armstrong – lead vocals, guitar

- Mike Dirnt – bass, backing vocals

- Tré Cool – drums, guitar and lead vocals on "All by Myself"

- Rob Cavallo, Green Day – producer, mixing

- Jerry Finn – mixing

- Neill King – engineer[65]

- Casey McCrankin – engineer

- Richie Bucher – cover artist

- Ken Schles – photography

- Pat Hynes – booklet artwork

Charts[]

Weekly charts[]

|

Year-end charts[]

Decade-end charts[]

|

Certifications[]

| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Argentina (CAPIF)[107] | Platinum | 60,000^ |

| Australia (ARIA)[108] | 5× Platinum | 350,000^ |

| Austria (IFPI Austria)[109] | Platinum | 50,000* |

| Belgium (BEA)[110] | Gold | 25,000* |

| Brazil (Pro-Música Brasil)[111] | Gold | 100,000* |

| Canada (Music Canada)[112] | Diamond | 1,000,000^ |

| Denmark (IFPI Danmark)[113] | 4× Platinum | 80,000 |

| Finland (Musiikkituottajat)[114] | Gold | 35,205[114] |

| France (SNEP)[115] | Gold | 100,000* |

| Germany (BVMI)[116] | 3× Gold | 750,000^ |

| Ireland (IRMA)[117] | 4× Platinum | 60,000^ |

| Italy (FIMI)[118] sales since 2009 |

Platinum | 50,000 |

| Japan (RIAJ)[119] | Platinum | 200,000^ |

| Netherlands (NVPI)[120] | Gold | 50,000^ |

| New Zealand (RMNZ)[121] | Platinum | 15,000^ |

| Poland (ZPAV)[122] | Gold | 50,000* |

| Spain (PROMUSICAE)[123] | Platinum | 100,000^ |

| Sweden (GLF)[124] | Gold | 50,000^ |

| Switzerland (IFPI Switzerland)[125] | Gold | 25,000^ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[126] | 3× Platinum | 900,000^ |

| United States (RIAA)[127] | Diamond | 10,000,000^ |

| Summaries | ||

| Europe (IFPI)[128] | Platinum | 1,000,000* |

|

* Sales figures based on certification alone. | ||

References[]

- ^ "Album Sales". GreenDay.fm. Retrieved August 30, 2020.

- ^ a b "500 Greatest Albums of All Time Rolling Stone's definitive list of the 500 greatest albums of all time". Rolling Stone. 2020. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Ultimate Albums: Green Day's "Dookie". VH1. 1994.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Green Day". Behind the Music. 2001. VH1.

- ^ a b "Green Day Biography". Billboard. Retrieved July 16, 2007.

- ^ "What Happened Next..." Guitar Legends. Archived from the original on September 27, 2006. Retrieved September 26, 2006.

- ^ a b "Green Day | The Early Years | 2017". Archived from the original on November 14, 2021. Retrieved January 22, 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ Smith, RJ (August 1999). "Top 90 Albums of the 90's". SPIN.

- ^ Grow, Kory. "See Green Day's Manic, Surprise Return to 924 Gilman". Rolling Stone. Rolling Stone, LLC. Retrieved July 11, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Billie Joe Armstrong Interview on VH1". VH1. Archived from the original on August 9, 2002. Retrieved July 16, 2007.

- ^ @billiejoe (February 9, 2011). "I wrote "having a blast" in cleveland..." (Tweet). Retrieved February 12, 2011 – via Twitter.

- ^ Mundy, Chris (January 26, 1995). "Green Day: Best New Band". Rolling Stone. Retrieved November 19, 2015.

- ^ "Green Day Music Videos". Green Day. Archived from the original on July 3, 2007. Retrieved July 20, 2007.

- ^ "Green Day single chart history". Billboard. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved July 16, 2007.

- ^ a b "UK album chart archives". everyhit.com. Archived from the original on July 17, 2007. Retrieved July 16, 2007.

- ^ Fricke, David (February 3, 2014). "'Dookie' at 20: Billie Joe Armstrong on Green Day's Punk Blockbuster". Rolling Stone. Retrieved January 29, 2015.

- ^ Richard Buskin. "Green Day: 'Basket Case'". Soundonsound.com. Archived from the original on November 1, 2013. Retrieved October 30, 2013.

- ^ "Interview with The Advocate magazine". The Advocate. Archived from the original on March 9, 2005. Retrieved July 27, 2007.

- ^ "Song Meanings". Green Day Authority. Archived from the original on October 11, 2007. Retrieved June 18, 2009.

- ^ Cizmar, Martin (February 18, 2014). "Where's Angus?". Willamette Week. Archived from the original on October 19, 2016. Retrieved October 14, 2016.

- ^ "Dookie". Ultimate Albums. Episode 2. March 17, 2002. VH1.

- ^ a b c Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Dookie – Green Day". AllMusic. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- ^ Gaar, Gillian (October 28, 2009). Green Day: Rebels With a Cause. ISBN 9780857120595.

- ^ "New Zealand album chart archives". charts.nz. Retrieved July 16, 2007.

- ^ "Diamond Certified Albums". RIAA. Archived from the original on July 25, 2013. Retrieved July 16, 2007.

- ^ a b "Green Day 'Dookie' Set: Billie Joe Armstrong & Rockers Perform 1994 Album In Entirety For London Show [WATCH] : Music News". Mstarz. August 23, 2013. Archived from the original on October 17, 2015. Retrieved September 2, 2013.

- ^ Raub, Jesse (June 22, 2010). "Green Day – Dookie". Alternative Press. Archived from the original on August 29, 2010. Retrieved August 22, 2015.

- ^ Payne, Chris (February 1, 2014). "Green Day's 'Dookie' at 20: Classic Track-By-Track Review". Billboard. Retrieved August 22, 2015.

- ^ DeRogatis, Jim (February 20, 1994). "Green Day, 'Dookie' (Warner Bros.)". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on November 18, 2018. Retrieved September 24, 2015.

- ^ Kot, Greg (March 4, 1994). "Green Day: Dookie (Reprise)". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved September 24, 2015.

- ^ Barker, Emily (January 29, 2014). "25 Seminal Albums From 1994 – And What NME Said At The Time". NME. Archived from the original on July 9, 2015. Retrieved July 8, 2015.

- ^ Hogan, Marc (May 7, 2017). "Green Day: Dookie". Pitchfork. Retrieved May 8, 2017.

- ^ Catucci, Nick (2004). "Green Day". In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). Simon & Schuster. pp. 347–48. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- ^ Eddy, Chuck (1995). "Green Day". In Weisbard, Eric; Marks, Craig (eds.). Spin Alternative Record Guide. Vintage Books. pp. 170–71. ISBN 0-679-75574-8.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (October 18, 1994). "Consumer Guide". The Village Voice. Retrieved August 22, 2015.

- ^ Lamb, Bill (July 17, 2013). "Green Day – Dookie". Top40.about.com. Archived from the original on September 9, 2013. Retrieved August 12, 2013.

- ^ "The Best Music of 1994". Time. December 26, 1994. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved July 21, 2007.

- ^ Pareles, Jon (January 5, 1995). "The Pop Life". New York Times. Retrieved July 21, 2007.

- ^ "Green Day". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on September 17, 2012. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ^ Strauss, Neil (February 5, 1995). "POP VIEW; Has Success Spoiled Green Day?". New York Times. Retrieved July 21, 2007.

- ^ Joe D'angelo (September 15, 2004). "How Green Day's Dookie Fertilized A Punk-Rock Revival". MTV.com. Retrieved June 17, 2014.

- ^ Melissa Bobbitt (April 8, 2014). "The Offspring's 'Smash' Turns 20". About.com. Archived from the original on July 12, 2014. Retrieved June 17, 2014.

- ^ Zac Crain (October 23, 1997). "Green Day Family Values – Page 1 – Music – Miami". Miami New Times. Archived from the original on May 22, 2014. Retrieved September 2, 2013.

- ^ "Green Day's 'Dookie' Turns 20: Musicians Revisit the Punk Classic – Features – Fuse". Fuse. Archived from the original on February 23, 2015. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ^ a b "1994– The 40 Best Records From Mainstream Alternative's Greatest Year – Rolling Stone". Rolling Stone. April 17, 2014. Retrieved May 23, 2014.

- ^ a b "10 Best Hard Rock Albums of 1994". Loudwire. May 20, 2014. Retrieved May 23, 2014.

- ^ "Superunknown: 50 Iconic Albums That Defined 1994". GuitarWorld.com. July 14, 2014. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- ^ "List of Dookie Accolades". Acclaimed Music. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved July 17, 2007.

- ^ "Kerrang! – The Kerrang! 100 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die". AcclaimedMusic.net. Retrieved July 16, 2007.

- ^ "Acclaimed Music – Classic Rock and Metal Hammer 200 List". AcclaimedMusic.net. Retrieved July 16, 2007.

- ^ Dimery, Robert – 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die; page 855

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. December 10, 2003. Archived from the original on January 20, 2013. Retrieved July 16, 2007.(subscription required)

- ^ "Rocklist.net....Rolling Stone (USA) End of Year Lists". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011.

- ^ "100 Best Albums of the Nineties: Green Day, 'Dookie'". Rolling Stone. April 27, 2011. Retrieved August 3, 2011.

- ^ "Spin Magazine – 100 Greatest Albums, 1985–2005". Archived from the original on August 11, 2007. Retrieved July 16, 2007.

- ^ "The Definitive 200". Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on August 13, 2007. Retrieved August 18, 2007.

- ^ "51 Greatest Pop Punk Albums Ever". Kerrang! (1586): 18–25. September 16, 2015.

- ^ VH1's VH1 40 Freakiest Concert Moments: #40 Mudstock – 2006

- ^ "Wood Stock 1994 Mudfight description". Chiff. Archived from the original on July 3, 2007. Retrieved July 16, 2007.

- ^ "When I Come Around Facts". Song Facts. Retrieved July 16, 2007.

- ^ "Green Day Tour Notes". Geek Stink Breath. Retrieved July 16, 2007.

- ^ "Green Day play 'Dookie' during Reading Festival 2013 headline show | News". Nme.Com. August 23, 2013. Retrieved February 25, 2014.

- ^ a b "Green Day – Dookie (Vinyl, LP, Album) at Discogs". Discogs. Retrieved May 23, 2014.

- ^ "Release "Dookie" by Green Day – MusicBrainz". MusicBrainz. Archived from the original on September 17, 2015. Retrieved May 23, 2014.

- ^ "Green Day: 'Basket Case' –". Archived from the original on November 8, 2016.

- ^ "Australiancharts.com – Green Day – Dookie". Hung Medien. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "Austriancharts.at – Green Day – Dookie" (in German). Hung Medien. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – Green Day – Dookie" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – Green Day – Dookie" (in French). Hung Medien. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "Top RPM Albums: Issue 2714". RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved August 2, 2021.

- ^ "Dutchcharts.nl – Green Day – Dookie" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "Eurochart Top 100 Albums - September 23, 1995" (PDF). Music & Media. Vol. 12 no. 38. September 23, 1995. p. 17. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ "Green Day: Dookie" (in Finnish). Musiikkituottajat – IFPI Finland. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de – Green Day – Dookie" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "Top 50 Ξένων Άλμπουμ: Eβδομάδα 11-17/6/2006" (in Greek). IFPI Greece. Archived from the original on June 17, 2006. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- ^ "Album Top 40 slágerlista – 1995. 25. hét" (in Hungarian). MAHASZ. Retrieved November 25, 2021.

- ^ "Irish-charts.com – Discography Green Day". Hung Medien. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "Classifica settimanale WK 12 (dal 17.03.1995 al 23.03.1995)" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana.

- ^ "Charts.nz – Green Day – Dookie". Hung Medien. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "Norwegiancharts.com – Green Day – Dookie". Hung Medien. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "Official Scottish Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "Swedishcharts.com – Green Day – Dookie". Hung Medien. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "Swisscharts.com – Green Day – Dookie". Hung Medien. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "Official Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "Green Day Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "Green Day Chart History (Heatseekers Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved June 1, 2021.

- ^ "Green Day Chart History (Top Catalog Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved June 1, 2021.

- ^ "Green Day Chart History (Vinyl Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved June 1, 2021.

- ^ "RPM Top 100 Albums of 1994". RPM. December 12, 1994. Archived from the original on June 21, 2013. Retrieved June 6, 2021.

- ^ "Top Billboard 200 Albums – Year-End 1994". Billboard. p. 20. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "ARIA Top 100 Albums for 1995". Australian Recording Industry Association. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "Jahreshitparade Alben 1995". austriancharts.at (in German). Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "Jaaroverzichten 1995 - Albums" (in Dutch). Ultratop. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "Rapports Annuels 1995 - Albums" (in French). Ultratop. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "Top Albums/CDs – Volume 62, No. 20, December 18 1995". RPM. December 18, 1995. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- ^ "Jaaroverzichten – Album 1995" (in Dutch). dutchcharts.nl. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "Year End Sales Charts – European Top 100 Albums 1995" (PDF). Music & Media. December 23, 1995. p. 14. Retrieved July 29, 2018.

- ^ "Top 100 Album-Jahrescharts" (in German). GfK Entertainment. Retrieved August 13, 2018.

- ^ "Top Selling Albums of 1995". Recorded Music NZ. Retrieved May 23, 2021.

- ^ "Årslista Album (inkl samlingar), 1995" (in Swedish). Sverigetopplistan. Retrieved May 23, 2021.

- ^ "Schweizer Jahreshitparade 2020" (in German). hitparade.ch. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "End of Year Album Chart Top 100 – 1995". Official Charts Company. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "Top Billboard 200 Albums – Year-End 1995". Billboard. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "The Official UK Albums Chart - Year-End 2001" (PDF). UKchartsplus.co.uk. Official Charts Company. p. 6. Retrieved May 31, 2021.

- ^ "The Top 200 Artist Albums of 2005" (PDF). Chartwatch: 2005 Chart Booklet. Zobbel.de. pp. 40–41. Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- ^ Geoff Mayfield (December 25, 1999). 1999 The Year in Music Totally '90s: Diary of a Decade – The listing of Top Pop Albums of the '90s & Hot 100 Singles of the '90s. Billboard. p. 20. Retrieved October 15, 2010.

- ^ "Discos de oro y platino" (in Spanish). Cámara Argentina de Productores de Fonogramas y Videogramas. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- ^ "ARIA Charts – Accreditations – 2011 Albums" (PDF). Australian Recording Industry Association. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- ^ "Austrian album certifications – Green Day – Dookie" (in German). IFPI Austria. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- ^ "Ultratop − Goud en Platina – albums 1995". Ultratop. Hung Medien. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- ^ "Brazilian album certifications – Green Day – Dookie" (in Portuguese). Pro-Música Brasil. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- ^ "Canadian album certifications – Green Day – Dookie". Music Canada. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- ^ "Danish album certifications – Green Day – Dookie". IFPI Danmark. Retrieved November 18, 2020.

- ^ a b "Green Day" (in Finnish). Musiikkituottajat – IFPI Finland. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- ^ "French album certifications – Green Day – Dookie" (in French). Syndicat National de l'Édition Phonographique. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- ^ "Gold-/Platin-Datenbank (Green Day; 'Dookie')" (in German). Bundesverband Musikindustrie. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- ^ "The Irish Charts - 2005 Certification Awards - Multi Platinum". Irish Recorded Music Association. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- ^ "Italian album certifications – Green Day – Dookie" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. Retrieved August 2, 2021.

- ^ "Japanese album certifications – Green Day – Dookie" (in Japanese). Recording Industry Association of Japan. Retrieved September 6, 2019. Select 1997年5月 on the drop-down menu

- ^ "Dutch album certifications – Greenday – Dookie" (in Dutch). Nederlandse Vereniging van Producenten en Importeurs van beeld- en geluidsdragers. Retrieved September 6, 2019. Enter Dookie in the "Artiest of titel" box.

- ^ "New Zealand album certifications – Green Day – Dookie". Recorded Music NZ. Retrieved June 2, 2021.

- ^ "Wyróżnienia – Złote płyty CD - Archiwum - Przyznane w 1996 roku" (in Polish). Polish Society of the Phonographic Industry. December 30, 1996. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- ^ Solo Exitos 1959–2002 Ano A Ano: Certificados 1991–1995. Solo Exitos 1959–2002 Ano A Ano. 2005. ISBN 84-8048-639-2.

- ^ "Guld- och Platinacertifikat − År 1987−1998" (PDF) (in Swedish). IFPI Sweden. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 17, 2011. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- ^ "The Official Swiss Charts and Music Community: Awards (Green Day; 'Dookie')". IFPI Switzerland. Hung Medien. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- ^ "British album certifications – Green Day – Dookie". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- ^ "American album certifications – Green Day – Dookie". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- ^ "IFPI Platinum Europe Awards – 1996". International Federation of the Phonographic Industry. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

External links[]

- Dookie at YouTube (streamed copy where licensed)

- Dookie at Discogs

- Dookie on Rate Your Music site

- 1994 albums

- Albums produced by Rob Cavallo

- Grammy Award for Best Alternative Music Album

- Green Day albums

- Reprise Records albums