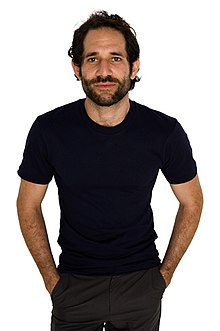

Dov Charney

Dov Charney | |

|---|---|

Dov Charney in 2008 | |

| Born | 31 January 1969 |

Dov Charney (born 31 January 1969) is a Canadian entrepreneur, clothing manufacturer and advocate for immigration reform in the United States. He is the founder of American Apparel, which until its bankruptcy in 2015, was one of the largest and most influential garment manufacturers in the United States.[1] Following his departure from American Apparel, Charney subsequently founded Los Angeles Apparel.[2]

Widely considered a pioneer in the manufacturing industry,[3] Charney has been recognized as an unconventional leader, attributed in large part to his early adoption of socially progressive company policies and American Apparel's provocative, unretouched ad campaigns.[4]

Early life[]

Charney was born in Montreal, Quebec. His father is an architect, and his mother an artist.[5] Charney is a nephew of architect Moshe Safdie.[6] He attended Choate Rosemary Hall, a private boarding school in Connecticut[7] and St. George's School of Montreal.[8] According to Charney, he was heavily influenced by both Montreal culture and his own Jewish heritage.[6][9]

While attending high school in the United States, Charney began importing Hanes and Fruit of the Loom t-shirts from the U.S. to his friends in Canada. In an interview with Vice, he described smuggling the shirts on Amtrak trains from New York to Montreal.[10]

American Apparel[]

Charney began selling t-shirts under the American Apparel name as early as 1989.[11] In 1990, he dropped out of Tufts University, borrowed $10,000 from his parents and established American Apparel in South Carolina.[12] Over the next several years, he spent time learning about manufacturing and wholesale before moving to Los Angeles in the mid-'90s. The company focused on crafting high-quality basics and by 1997, Charney had moved all manufacturing into a factory located in downtown Los Angeles.[13]

American Apparel products were marketed towards "young metropolitan adults."[14] The basic, logo-free branding appealed to younger consumers wary of corporate branding.[15] Rather than compete with mass-market companies like Fruit of the Loom, American Apparel flourished in its "high-end niche by leveraging product quality, hip design, and the appeal of its anti-sweatshop politics."[11]

The company had about $12 million in sales by 2001. In 2003, Charney opened the first store in L.A.'s Echo Park neighborhood, followed by one each in New York and Montreal. Within two years, the company had expanded to Europe and opened 65 new stores. By 2006, there were 140 total stores and in the following year, American Apparel had become the largest T-shirt manufacturer in America. One of only a few clothing companies exporting "Made in the USA" products, it sold about $125 million of domestically manufactured clothing outside of the US.[16]

In 2009, it expanded to 281 total retail locations, making it "the fastest retail roll-out in American history."[17] In 2014, the company reported record sales of $634 million dollars.

Ad campaigns[]

American Apparel under Charney's leadership was known for its simple and provocative ads, which rarely used professional models and whom were often chosen personally by Charney from local hangouts and stores.[18] He shot many of the advertisements himself[19] and was criticized for featuring models in sexually provocative poses. However, the campaigns were also lauded for honesty and lack of airbrushing.[20][21]

In 2012, the company made headlines when it debuted an ad campaign featuring mature model Jacky O'Shaughnessy. The photos generated considerable buzz and were generally well-received.[22]

American Apparel again stirred controversy in 2014 when they displayed mannequins with pubic hair in the window of their Lower East Side store.[23] Regarding the use of the mannequins, the company told Elle Magazine:

"American Apparel is a company that celebrates natural beauty, and the Lower East Side Valentine's Day window continues that celebration. We created it to invite passerbys to explore the idea of what is 'sexy' and consider their comfort with the natural female form. This is the same idea behind our advertisements, which avoid many of the photoshopped and airbrushed standards of the fashion industry. So far we have received positive feedback from those that have commented, and we're looking forward to hearing more points of view."[23]

Activism[]

Under Charney's leadership, American Apparel took a leading role in the promotion of a number of prominent social causes.

Legalize LA[]

Legalize LA was an immigration reform campaign conceived by Charney and promoted by American Apparel beginning in 2004. The campaign featured billboards and full-page ads in national publications as well as t-shirts sold in retail locations emblazoned with the words "Legalize LA." Proceeds from the sale of the shirts were donated to immigration reform advocacy groups. The campaign called for the overhaul of immigration laws so as to create a legal path for undocumented workers to gain citizenship in the United States.[24][25]

Legalize Gay[]

In November 2008, after the passing of Proposition 8, which banned same-sex marriages in California, Dov Charney and American Apparel created "Legalize Gay" T-shirts to hand out to protesters at rallies. The positive reaction led American Apparel to sell the same shirts in stores and online.[26]

Factory conditions[]

In an interview with Vice.tv, Charney spoke out against the poor treatment of fashion workers in developing countries and refers to the practices as "slave labor" and "death trap manufacturing." Charney proposed a "Global Garment Workers Minimum Wage" and discussed in detail many of the inner workings of the modern fast fashion industry practices that creates dangerous factory conditions and disasters like the 2013 Savar building collapse on May 13, which had the death toll of 1,127 and 2,500 injured people who were rescued from the building alive.[27]

Dismissal[]

American Apparel publicly suspended Charney on 18 June 2014, stating that they would terminate him for cause in 30 days. The termination letter given to Charney alleged that he had engaged in conduct that "repeatedly put himself in a position to be sued by numerous former employees for claims that include harassment, discrimination and assault."[2]

Paula Schneider, who took over as company CEO, claimed Charney was fired "for violating our sexual harassment and our anti-discrimination policy" and "for misuse of corporate assets."[28]

According to reports, Charney was blindsided by news of his termination, calling it a "coup." In court filings by his attorneys, it was alleged that the American Apparel CFO had sketched out a plan to oust Charney, and that he was persuaded to sign a disastrous settlement that left him with no job and no control of the company, despite being the largest shareholder. Charney also argued that the investigation was biased because it was conducted by people who wanted him out, and that he has never been charged with any crime or found guilty or liable for any of the accusations against him.[2]

In December 2014, Charney was terminated as a Chief Executive Officer after months of suspension. In December 2014, Charney told Bloomberg Businessweek he was down to his last $100,000 and that he was sleeping on a friend's couch in Manhattan.[29] Following his suspension as CEO in the summer of 2014, Charney teamed up with the Standard General hedge fund to buy stocks of the company to attempt a takeover.[30] In 2016, American Apparel board dismissed a $300 million offer from Hagan Group that pushed for Charney's comeback.[31]

Los Angeles Apparel[]

In 2016, Charney founded Los Angeles Apparel. He opened Los Angeles Apparel's first factory in South Central Los Angeles, with aims of replicating the successes he experienced in the 1990s with supplying wholesale clothing. The origins are similar to those he deployed while expanding American Apparel. Especially with the manufacturing of all garments in the United States, to offer better completion times than competitors.[32] When interviewed by Vice News regarding his new venture, Charney said, "my previous company had an effect on the culture of young adults...I want to reconnect and do that again before I die."[33]

The company grew to over 350 staff during the second year of operation. During an interview with Bloomberg, Charney drew comparisons to the growth he experienced with American Apparel calling it the equivalent of "year eight." Charney expected the fashion line to grow to $20 million in revenue by 2018.[32]

Similar to American Apparel, the manufacturing of all Los Angeles Apparel garments are kept in the US to maintain low lead times and offer better completion times than overseas competitors. Los Angeles Apparel also provides livable wages to factory workers.[34]

Following the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, Charney repurposed his business operations to help increased demand for PPE (Personal Protective Equipment).[35] According to the Los Angeles Times, Charney spotted shortages as early as February and this is when his apparel company began to consider manufacturing face masks.[36]

Charney was interviewed in March 2020 by a number of media outlets, speaking about his desire to turn Los Angeles Apparel into a medical equipment manufacturer during the pandemic. Los Angeles Apparel then began manufacturing face masks and medical gowns at the facility in South Central. Charney told The New York Times that he aimed to create 300,000 masks and 50,000 gowns each week.[37] Los Angeles Apparel launched the new face mask in over a dozen different colors. In an interview, Charney said he was "losing money on the venture," as he was giving many of them away.[38] This included donating large numbers to key workers in healthcare and law enforcement in LA, Seattle, New York City and Las Vegas.[36]

Controversy[]

Charney has been the subject of several sexual harassment lawsuits, at least five since the mid-2000s, all of which were settled, dismissed, or remanded to private arbitration.[39][40][41][42][43] He has never been found to have committed sexual harassment.[44] Charney's lawyer, Keith Fink, told Business Insider that, "In many instances, cases were defeated or dismissed. In other instances, cases were settled because the insurance company whose only goal is to save total dollars wanted to stop the legal bleeding on these cases."[44]

Charney maintained his innocence, telling CNBC that "allegations that I acted improperly at any time are completely a fiction."[45] The company and independent media outlets publicly accused lawyers in the lawsuits against American Apparel of extortion and of "shaking the company down."[46][47][48][49][50][51]

In 2004, Claudine Ko of Jane magazine[52] published an essay narrating that Charney began masturbating in front of her while she was interviewing him.[20][53][54][55] The article's publication brought extensive press to Charney. In a follow-up to her first article, Ko wrote that her article had been misconstrued, stating that her encounter with Charney "was being used to feed a flawed cliche where men are evil and omnipotent while women are mute victims lacking free will." She further questioned the notion that she had been taken advantage of: "Who was really exploited? We both were—American Apparel got press, I got one hell of a story. And that's it."[56] The article's publication brought extensive press to the company and Charney, who later responded that he believed that the acts had been done consensually, in private and outside the article's bounds.[57][58][59][60]

Personal life[]

Charney lives in Garbutt House, a historic mansion atop a hill in Silver Lake designed by Frank Garbutt, an early movie pioneer and industrialist.[46] The house is made entirely out of concrete due to Garbutt's fear of fire. The house often functions as a dormitory for out-of-town workers doing business at company headquarters.[46] During his time at American Apparel Charney was consumed with work, often sleeping in his office at the company's factory, leaving little separation between his personal and work life.[46]

Awards[]

- 2005, "Marketing Excellence Award" at the LA Fashion Awards.

- 2008, "Retailer of the Year" at the Michael Awards for the Fashion Industry.

- 2009, Charney was a finalist for TIME Magazine's annual list of the '100 most influential people in the world.'[61]

References[]

- ^ "The rise and fall of American Apparel". the Guardian. 25 August 2010. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Edwards, Jim. "Inside the 'conspiracy' that forced Dov Charney out of American Apparel". Business Insider. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ "Los Angeles Entrepreneurs Named Ernst & Young Entrepreneur Of The Year 2004 Award Recipients". www.businesswire.com. 30 June 2004. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ "Sexy Sweats Without the Sweatshop". ABC News. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ Jewish Journal, Unfashionable Crisis, 29 July 2005.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Silcoff, Mireille. "A real shirt-disturber: Dov Charney conquered America with his fitted t-shirts and posse of strippers". Saturday Post. Archived from the original on 6 May 2008. Retrieved 6 April 2008.

- ^ Haskell, Kari (18 September 2006). "An Interview With American Apparel Founder Dov Charney". Debonair Magazine. Archived from the original on 6 April 2008. Retrieved 24 December 2016.

- ^ St. George Alumni Archived 22 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Morissette, Caroline (1 April 2005). "Dov Charney at McGill". Bull and Bear. Archived from the original on 4 February 2014. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ^ Friedersdorf, Conor (5 June 2013). "How the Head of American Apparel Got His Start: Smuggling Tees into Canada on Amtrak". The Atlantic.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lewis, Tanya. "CORPORATE CASE STUDY: Big-mouthed, big-hearted leader brings apparel outfit notoriety". www.prweek.com. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ^ "Dov Charney's American Dream: The rise, fall and comeback of an apparel empire". Retail Dive. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ^ "Segment of Modern Marvels: Cotton". The History Channel via AmericanApparel.net. Archived from the original on 21 December 2007. Retrieved 25 November 2007.

- ^ Jamie Wolf (23 April 2006). "And You Thought Abercrombie & Fitch Was Pushing It?". The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved 25 November 2007.

- ^ La Ferla, Ruth (3 November 2004). "Building a Brand By Not Being a Brand". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 March 2008.

- ^ "American Apparel: The Rise, Fall and Rebirth of an All-American Business". The Fashion Law. 20 August 2017. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- ^ "Dov Charney's American Dream: The rise, fall and comeback of an apparel empire". Retail Dive. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- ^ Rapoport, Adam (June 2004). "T (Shirts) and A". GQ. "What makes American Apparel's female models so appealing is that most of them are not models. They are girls whom Charney meets at bars, restaurants, trade shows—pretty much anywhere."

- ^ Palmeri, Christopher (27 June 2005). "Living on the Edge at American Apparel". Businessweek. Archived from the original on 24 March 2008. Retrieved 22 March 2008. "Charney takes many of the photos himself, often using company employees as models as well as people he finds on the street."

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stossel, John (2 December 2005). "Sexy Sweats Without the Sweatshop". ABC News. Retrieved 21 March 2008.

- ^ Morford, Mark (24 June 2005). "Porn Stars in My Underwear". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on 10 March 2008. Retrieved 21 March 2008.

- ^ Chernikoff, Leah Rose (19 February 2014). ""Legs in the Air? Great, Let's Go": Jacky O'Shaughnessy on Modeling for American Apparel at 62". ELLE. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Matthews, Natalie (16 January 2014). "American Apparel Tells Us Why They're Using Mannequins With Pubic Hair". ELLE. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- ^ Story, Louise (18 January 2008). "Politics Wrapped in a Clothing Ad". The New York Times.

- ^ "American Apparel takes stand on immigration". Reuters. 28 October 2008.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 21 February 2009. Retrieved 23 June 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ VICE (29 May 2013). "Dov Charney on Modern Day Sweat Shops: VICE Podcast 006". YouTube. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ "Former American Apparel CEO Dov Charney Speaks Out for First Time Since Ouster". ABC News. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ "American Apparel Founder Says He's Down to Last $100,000". Bloomberg.com. 22 December 2014. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ Peterson, Hayley. "Ousted American Apparel CEO Dov Charney Claims He Was Robbed By A Hedge Fund". Business Insider. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ "What happened when Dov Charney tried to get American Apparel back". The Independent. 15 January 2016. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Townsend, Matthew (12 July 2017). "Dov Charney Couldn't Keep American Apparel, So He Restarted It". Bloomberg.

- ^ Derrick, Jayson (14 September 2017). "Remember American Apparel's Dov Charney? He's Back With A New Business Idea". Benzinga. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ Abarbanel, Aliza. "Dov Charney Is Back Making Sexualized Basics". www.refinery29.com. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ "How your business can help fight coronavirus: One brand's pivot to making masks". FastCompany. 23 March 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Schmidt, Ingrid (24 March 2020). "Fashion brands are making face masks, medical gowns for the coronavirus crisis". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Testa, Jessica (21 March 2020). "Christian Siriano and Dov Charney Are Making Masks and Medical Supplies Now". The New York Times.

- ^ Pierce, Tony (2 April 2020). "Dov Charney's New Passion: Face Masks". Los Angeleno.

- ^ Holson, Laura M. (23 March 2011). "Dov Charney of American Apparel Named in Harassment Suit". The New York Times.

- ^ Covert, James (28 March 2010). "American Apparel Struggles to Stay Afloat". New York Post. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- ^ Brennan, Ed (18 May 2009). "Woody Allen reaches $5m settlement with head of American Apparel". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 22 May 2009. Quote: "Charney has been involved in several highly-publicised sexual harassment suits brought by former employees, none of which were proven."

- ^ Sefton, Eliot (3 September 2009). "Dov Charney's LA-based clothing company loses 1,600 staff and sees yet another advert banned". The First Post. Archived from the original on 8 September 2009. Retrieved 11 September 2009.

Charney has been the subject of several, unproven, sexual harassment suits and claims to have been victimised by the media in the past. He said that he used Woody Allen in his company's ads because he wanted to draw attention to the way he and Allen—both high-profile Jews—had been treated.

- ^ "American Apparel CEO Dov Charney's 'Sex Slave' Lawsuit Thrown Out". The Huffington Post. 22 March 2012. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Biron, Bethany (22 August 2019). "15 brands that are surprisingly not American, from Burger King to American Apparel". Business Insider. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ American Apparel CEO: Tattered, but Not Torn Archived 20 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine CNBC.com Jane Wells 4/10/12 "The company is also trying to recover from a litany of lawsuits against Charney, including a sex slave lawsuit that was thrown out last month"

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Holson, Laura (13 April 2011). "He's Only Just Begun to Fight". THe New York Times. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ Heller, Matthew (28 October 2008). "Fashion Mogul 'Fakes' Arbitration in Harassment Case". On Point. Archived from the original on 4 December 2008. Retrieved 21 November 2008.

The 'confidential arbitration' was in fact a charade. One of Nelson's attorneys, the 2nd District said, later described it as 'a 'fake arbitration' designed to produce a press release calculated to blunt negative media attention.'

- ^ Slater, Dan (4 November 2008). "The Story Behind American Apparel's Sham Arbitration". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 5 November 2008.

The court went on to say that 'the proposed press release is materially misleading — among other things, no real arbitration of a dispute occurred and [the] plaintiff received $1.3 million in compensation.'

- ^ Stein, Sadie (31 October 2008). "Tangled Webs: Dov Charney's Court Case is Totally Complicated". Jezebel. Retrieved 4 November 2008.

In response, Ms. Nelson's lawyer, Mr. Fink, devised a settlement agreement whereby his client would agree to certain stipulations amounting to a confession that her charges of sexual harassment were bogus, and that she had never been subject to any harassment or a hostile work environment.

- ^ Nolan, Hamilton (April 2011). "American Shakedown? Sex, Lies and the Dov Charney Lawsuit". Gawker. Archived from the original on 2 May 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ "Ex-workers say American Apparel posted nude pix online". Reuters. April 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ Nesvig, Kara (4 October 2007). "Unkempt, Urban, Ubiquitous". Minnesota Daily. Archived from the original on 20 April 2008. Retrieved 28 April 2008. Archived at americanapparel.net Archived 18 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Sexy marketing or sexual harassment? - Dateline NBC | NBC News". NBC News. 28 July 2006. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ^ "'Jewish hustler'—potty mouth and pervert—means no offense | The God Blog". Jewish Journal. 3 June 2008. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ^ "american apparel". Claudinenko.com. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ^ "claudine ko - american apparel 2". www.claudineko.com. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ "The company calls it "a social situation which...unfortunately was exploited in order to sell magazines." American Apparel CEO Trial Starts Today Archived 15 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine CNBC. Margaret Brennan. 28 February 2008.

- ^ "I've never done anything sexual that wasn't consensual," Charney says. The reporter, Claudine Ko, confirmed his take on events to BusinessWeek." Living on the Edge at American Apparel

- ^ "Within the context of a flirtatious conversation about sexuality and the pleasure Charney derives from masturbation with a willing partner, he decided to demonstrate for Ko, and it became a repeated motif in their later encounters. The article left a lasting impression of him as a boss who can't keep it in his pants," The New York Times "And You Thought Abercrombie and Fitch Was Pushing It"

- ^ "I was a younger man" he says, wearily. "The lines were blurred between paramour and reporter." The reporter has said that her tape recorder or notebook was in full view at all times and that the relationship was professional." Portfolio profile of Charney Archived 20 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The rise and fall of American Apparel". the Guardian. 25 August 2010. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Dov Charney |

- Canadian fashion designers

- Canadian retail chief executives

- California people in fashion

- 1969 births

- Living people

- Canadian expatriates in the United States

- Businesspeople from Los Angeles

- Businesspeople from Montreal

- Canadian Jews

- Canadian people of Lebanese-Jewish descent

- Jewish fashion designers

- Anglophone Quebec people

- Choate Rosemary Hall alumni

- Sexual misconduct allegations

- Tufts University alumni

- Canadian company founders

- Canadian people of Israeli descent

- 21st-century Canadian businesspeople