COVID-19 pandemic in the United States

| COVID-19 pandemic in the United States | |

|---|---|

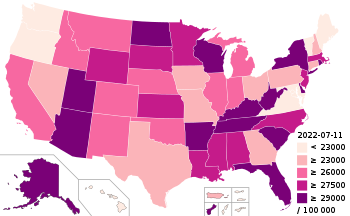

COVID-19 cases per 100,000 people by state, as of August 16 | |

| Disease | COVID-19 |

| Virus strain | SARS-CoV-2 |

| Location | United States |

| First outbreak | Wuhan, Hubei province, China[1] |

| Index case | Chicago, Illinois (earliest known arrival)[2] Everett, Washington (first case report)[3] |

| Arrival date | January 13, 2020[4] (1 year, 7 months, 1 week and 4 days ago) |

| Confirmed cases | |

| Suspected cases‡ | 120,259,370 (CDC estimate in May 2021)[7] |

| Recovered |

|

Deaths | 618,591 (CDC)[5] |

| Fatality rate |

|

| Vaccinations |

|

| Government website | |

| coronavirus | |

| ‡Suspected cases have not been confirmed by laboratory tests as being due to this strain, although some other strains may have been ruled out. | |

The COVID-19 pandemic in the United States is part of the worldwide pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). More than 37.9 million confirmed cases have been reported since January 2020, with more than 629,000 deaths, the most of any country, and the twenty-third-highest per capita worldwide.[6][9] As many infections have gone undetected, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated that, as of May 2021, there could be a total 120.2 million infections in the United States, or more than a third of the total population.[10][7] The U.S. has about one-fifth of the world's confirmed cases and deaths. COVID-19 was the third-leading cause of death in the U.S. in 2020, behind heart disease and cancer.[11] U.S. life expectancy dropped by 3 years for Hispanic Americans, 2.9 years for African Americans, and 1.2 years for white Americans from 2019 to 2020.[12]

On December 31, 2019, China announced the discovery of a cluster of pneumonia cases in Wuhan. The first American case was reported on January 20, and President Donald Trump declared the U.S. outbreak a public health emergency on January 31. Restrictions were placed on flights arriving from China,[13][14] but the initial U.S. response to the pandemic was otherwise slow, in terms of preparing the healthcare system, stopping other travel, and testing.[15][16][17][a] Meanwhile, Trump remained optimistic and was accused by his critics of underestimating the severity of the virus.

The first known American deaths occurred in February. On March 6, 2020, Trump allocated $8.3 billion to fight the outbreak and declared a national emergency on March 13. The government also purchased large quantities of medical equipment, invoking the Defense Production Act of 1950 to assist.[19] By mid-April, disaster declarations were made by all states and territories as they all had increasing cases. A second wave of infections began in June 2020, following relaxed restrictions in several states, leading to daily cases surpassing 60,000. By mid-October, another surge of cases led to over 200,000 infections daily by January 2021.[20][21]

Vaccines became available in December 2020 under emergency use, and one was officially approved by the FDA on August 23, 2021.[22] Vaccine hesitancy in parts of the country, however, has hampered vaccination efforts since they became available.[23] Dr. Anthony Fauci, President Biden's chief medical adviser, blamed misinformation for most of the hesitancy, suggesting that previous pandemics, such as Polio, would still be spreading today without vaccines.[24] A number of celebrities thoughout 2021 have advocated receiving a vaccine, publishing their own vaccinations as an example.

A fourth rise in infections began in late March amidst the rise of the Alpha variant, a more easily transmissible variant from the United Kingdom. That was followed by a rise of the Delta variant, an even more infectious mutation, leading to encreased efforts to ensure safety. State and local responses to the pandemic have included mask mandates, prohibition and cancellation of large-scale gatherings (including festivals and sporting events), stay-at-home orders, and school closures.[25] Disproportionate numbers of cases have been observed among Black and Latino populations,[26][27][28] as well as elevated levels of vaccine hesitancy,[29][30] and there were reported incidents of xenophobia and racism against Asian Americans.[31] Clusters of infections and deaths have occurred in many areas.[b]

Timeline

December 2019 to April 2020

In late November 2019, coronavirus infections had first broken out in Wuhan, China.[34][35] China publicly reported the cluster on December 31, 2019.[3] After China confirmed that the cluster of infections was caused by a novel infectious coronavirus[3] on January 7, 2020, the CDC issued an official health advisory the following day.[36] On January 20, the World Health Organization (WHO) and China both confirmed that human-to-human transmission had occurred.[37] The CDC immediately activated its Emergency Operations Center (EOC) to respond to the outbreak in China.[38] Also, the first report of a COVID-19 case in the U.S. was publicly reported,[3] though the All of Us study (released in 2021) showed five states already had cases weeks earlier.[39] After other cases were reported, on January 30, the WHO declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) – its highest level of alarm[40] – warning that "all countries should be prepared for containment."[41][42][d] The same day, the CDC confirmed the first person-to-person case in the U.S.[44] The next day, the country declared a public health emergency.[45] Although by that date there were only seven known cases in the U.S., the HHS and CDC reported that there was a likelihood of further cases appearing in the country.[45]

The Trump administration evacuated American nationals from Wuhan in late January.[46] On February 2, the U.S. enacted travel restrictions to and from China.[14] On February 6, the earliest confirmed American death with COVID-19 (that of a 57-year-old woman) occurred in Santa Clara County, California. The CDC did not report its confirmation until April 21,[47] by which point nine other COVID-19 deaths had occurred in Santa Clara County.[48] The virus had been circulating undetected at least since early January and possibly as early as November.[49] On February 25, the CDC warned the American public for the first time to prepare for a local outbreak.[50][51] The next day, New York City saw the sickening of its "patient zero", Manhattan attorney Lawrence Garbuz, then thought to be the first community-acquired case.[52][53][54] In February, Vice President Mike Pence took over for Secretary Alex Azar as chair of the White House Coronavirus Task Force.[55]

By March 11, the virus had spread to 110 countries, and the WHO officially declared a pandemic.[25] The CDC had already warned that large numbers of people needing hospital care could overload the healthcare system, which would lead to otherwise preventable deaths.[56][57] Dr. Anthony Fauci said the mortality from the coronavirus was ten times higher than the common flu.[58] By March 12, diagnosed cases of COVID-19 in the U.S. exceeded a thousand.[59] On March 16, the White House advised against any gatherings of more than ten people.[60] Three days later, the United States Department of State advised U.S. citizens to avoid all international travel.[61]

By the middle of March, all fifty states were able to perform tests with a doctor's approval, either from the CDC or from commercial labs. However, the number of available test kits remained limited, which meant the true number of people infected had to be estimated.[62] As cases began spreading throughout the nation, federal and state agencies began taking urgent steps to prepare for a surge of hospital patients. Among the actions was establishing additional places for patients in case hospitals became overwhelmed.[63]

Throughout March and early April, several state, city, and county governments imposed "stay at home" quarantines on their populations to stem the spread of the virus.[64] By March 27, the country had reported over 100,000 cases.[65] On April 2, at President Trump's direction, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and CDC ordered additional preventive guidelines to the long-term care facility industry.[66] On April 11, the U.S. death toll became the highest in the world when the number of deaths reached 20,000, surpassing that of Italy.[67] On April 19, the CMS added new regulations requiring nursing homes to inform residents, their families and representatives, of COVID-19 cases in their facilities.[68] On April 28, the total number of confirmed cases across the country surpassed 1 million.[69]

May to August 2020

By May 27, less than four months after the pandemic reached the U.S., 100,000 Americans had died with COVID-19.[70] State economic reopenings and lack of widespread mask orders resulted in a sharp rise in cases across most of the continental U.S. outside of the Northeast.[71] A study conducted in May 2020 indicated that the true number of COVID-19 cases in the United States was much higher than the number of confirmed cases with some locations having 6–24 times higher infections, which was further confirmed by a later population-wide serosurvey.[72][73][74]

On July 6, the United States Department of State announced the country's withdrawal from WHO effective July 6, 2021.[75] On July 10, the CDC adopted the Infection Fatality Ratio (IFR), "the number of individuals who die of the disease among all infected individuals (symptomatic and asymptomatic)", as a new metric for disease severity.[76] In July, U.S. PIRG and 150 health professionals sent a letter asking the federal government to "shut it down now, and start over".[77] In July and early August, requests multiplied, with a number of experts asking for lockdowns of "six to eight weeks"[78] that they believed would restore the country by October 1, in time to reopen schools and have an in-person election.[79]

In August, over 400,000 people attended the 80th Sturgis Motorcycle Rally in Sturgis, South Dakota, and from there, at least 300 people in more than 20 states were infected.[80] The CDC followed up with a report on the associated 51 confirmed primary event-associated cases, 21 secondary cases, and five tertiary cases in the neighboring state of Minnesota, where one attendee died of COVID-19.[81] The U.S. passed 5 million COVID-19 cases by August 8.[82]

September to December 2020

On September 22, the U.S. passed 200,000 deaths, according to data from Johns Hopkins University.[83] In early October, an unprecedented series of high-profile U.S. political figures and staffers announced they had tested positive for COVID-19.[84][85] On October 2, Trump announced on Twitter that both he and the First Lady had tested positive for the coronavirus and would immediately quarantine.[86][85] Trump was given an experimental Regeneron product with two monoclonal antibodies[87][e] and taken to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center,[89] where he was given remdesivir and dexamethasone.[90]

USA Today studied the aftermath of presidential election campaigning, recognizing that causation was impossible to determine. Among their findings, cases increased 35 percent compared to 14 percent for the state after a Trump rally in Beltrami County, Minnesota. One case was traced to a Joe Biden rally in Duluth, Minnesota.[91]

On November 9, President-elect Biden's transition team announced his COVID-19 Advisory Board.[92] On the same day, the total number of cases had surpassed ten million[93] while the total had risen by over a million in the ten days prior, averaging 102,300 new cases per day.[94] Pfizer also announced that its COVID-19 vaccine may be up to ninety percent effective.[95][96] In November, the Trump administration reached an agreement with a number of retail outlets, including pharmacies and supermarkets, to make the COVID-19 vaccine free once available.[97]

In spite of recommendations by the government not to travel, more than 2 million people flew on airlines during the Thanksgiving period.[98] On December 8, the U.S. passed 15 million cases, with about one out of every 22 Americans having tested positive since the pandemic began.[99] On December 14, the U.S. passed 300,000 deaths, representing an average of more than 961 deaths per day since the first known death on February 6. More than 50,000 deaths were reported in the past month, with an average of 2,403 daily deaths occurring in the past week.[100]

On December 24, following concerns over a probably more easily transmissible new SARS-CoV-2 variant from the United Kingdom, later called Alpha, the CDC announced testing requirements for American passengers traveling from the UK, to be administered within 72 hours, starting on December 28.[101][102] On December 29, the U.S. reported the first case of this variant in Colorado. The patient had no travel history, leading the CDC to state, "Given the small fraction of US infections that have been sequenced, the variant could already be in the United States without having been detected."[103]

January to April 2021

On January 1, 2021, the U.S. passed 20 million cases, representing an increase of more than a million over the past week and 10 million in less than two months.[104][105] On January 6, the CDC announced that it had found at least 52 confirmed cases of the Alpha variant, and it also stressed that there could already be more cases in the country.[106] In the following days, more cases of the variant were reported in other states, leading former CDC director Tom Frieden to express his concerns that the U.S. will soon face "close to a worst-case scenario".[107] It was believed the variant had been present in the U.S. since October.[108]

On January 19, the U.S. passed 400,000 deaths, just five weeks after the country passed 300,000 deaths.[109] On January 22, the U.S. passed 25 million cases, with one of every 13 Americans testing positive for COVID-19.[110] By March 5, more than 2,750 cases of COVID-19 variants were detected in 47 states; Washington, D.C.; and Puerto Rico.[111] In the first prime time address of his presidency on March 11, Biden announced his plan to push states to make vaccines available to all adults by May 1, with the aim of making small gatherings possible by July 4.[112] On March 24, the U.S. passed 30 million cases, just as a number of states began to expand the eligibility age for COVID-19 vaccines.[113] Experts began warning against public relaxation of COVID-19 mitigation measures as vaccines continue to be administered, with one, CDC director Rochelle Walensky, warning of a new rise in cases.[114]

By April 7, the Alpha variant had become the dominant COVID-19 strain in the U.S.[115] On April 12, the U.S. reported its first cases of a new "double mutant" SARS-CoV-2 variant from India, later called Delta, in California.[116] By April 25, the country's seven-day average of new infections was reported to be decreasing, but concerns were raised about drops in vaccine demand in certain parts of the U.S., which were attributed to vaccine hesitancy.[117][118][119] On April 29, the CDC estimated that roughly 35% of the U.S. population had been infected with the virus as of March 2021, about four times higher than the official reported numbers.[10]

May to August 2021

On May 4, Biden announced a new goal of having 70 percent of all adults in the U.S. receive at least one COVID-19 vaccine shot by July 4, along with steps to vaccinate teenagers and more inaccessible populations.[120] The country ultimately did not reach that goal, with only 67 percent of the overall adult population having done so by July 4.[121] On May 6, a study by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation estimated that the true COVID-19 death toll in the U.S. was more than 900,000 people.[122] On May 9, Dr. Fauci confirmed that the U.S. death toll was likely undercounted.[123]

On May 13, the CDC changed its guidance and said that fully vaccinated individuals do not need to wear masks in most situations.[124] Some states ended their mask mandates shortly after, while others maintained the mandate. The CDC was criticized for the confusion resulting from the announcement, as it did not remove existing state and local mandates. The guidance also did not remove the federal mask mandate on public transportation.[125] On June 15, the U.S. passed 600,000 deaths, though the number of daily deaths had decreased due to vaccination efforts.[126]

By late June, COVID-19 cases rose again, especially in Arkansas, Nevada, Missouri, and Wyoming. The rising numbers were believed to be attributable to the Delta variant.[127] By July 7, the Delta variant had surpassed the Alpha variant to become the dominant COVID-19 strain in the U.S., according to CDC data.[128] By July 20, the Delta variant accounted for 83 percent of all sequenced cases, according to the CDC.[129] On August 1, the U.S. passed 35 million cases.[130]

By early and mid-August, hospitals in some states with low vaccination rates began to exceed capacity. On August 9, Arkansas reported only 8 open ICU beds in the entire state.[131] Southwestern Louisiana, with the lowest vaccination rate in the state, began sending patients to Texas,[132] but in that state at least 50 hospitals had already reached or exceeded 100% of ICU capacity.[133] One New Orleans patient suffering a heart attack was bounced from six hospitals before being allowed into an emergency room.[134] The surge of preventable illnesses among the unvaccinated created a shortage of nurses in hotspots and a request to postpone all elective medical procedures in Texas.[134] Shortages of beds forced patients to wait in emergency rooms, in one case in Hawaii for up to 30 hours. ER backlogs caused patients in some locations to wait for hours in ambulances, causing delays answering 911 medical calls.[134] The entire state of Mississippi, with the second-lowest state vaccination rate in the country, ran out of ICU beds. The only Level 1 Trauma Center began building a field hospital in its parking garage, staffed with medical personnel from states with higher vaccination rates.[135]

One-quarter of the U.S. population resides in eight states—Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, Nevada and Texas—but, by mid-August, these states together had one-half of U.S. COVID-19 hospitalizations.[136]

Responses

On January 28, the CDC updated its China travel recommendations to level 3, its highest alert.[137] On February 8, the WHO's director-general announced that a team of international experts had been assembled to travel to China and he hoped officials from the CDC would also be part of that mission.[138][139] In late January, Boeing announced a donation of 250,000 medical masks to help address China's supply shortages.[140] On February 7, the State Department said it had facilitated the transportation of nearly eighteen tons of medical supplies to China, including masks, gowns, gauze, respirators, and other vital materials.[141] On the same day, U.S. Secretary of State Pompeo announced a $100 million pledge to China and other countries to assist with their fights against the virus.[142]

Contact tracing is a tool to control transmission rates during the reopening process. Some states like Texas and Arizona opted to proceed with reopening without adequate contact tracing programs in place. Health experts have expressed concerns about training and hiring enough personnel to reduce transmission. Privacy concerns have prevented measures such as those imposed in South Korea where authorities used cellphone tracking and credit card details to locate and test thousands of nightclub patrons when new cases began emerging.[143] Funding for contact tracing is thought to be insufficient, and even better-funded states have faced challenges getting in touch with contacts. Congress has allocated $631 million for state and local health surveillance programs, but the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security estimates that $3.6 billion will be needed. The cost rises with the number of infections, and contact tracing is easier to implement when the infection count is lower. Health officials are also worried that low-income communities will fall further behind in contact tracing efforts which "may also be hobbled by long-standing distrust among minorities of public health officials".[144] As of July 1, only four states are using contact tracing apps as part of their state-level strategies to control transmission. The apps document digital encounters between smartphones, so the users will automatically be notified if someone they had contact with has tested positive. Public health officials in California claim that most of the functionality could be duplicated by using text, chat, email, and phone communications.[145]

In the United States, remdesivir is indicated for use in adults and adolescents (aged twelve years and older with body weight at least 40 kilograms (88 lb)) for the treatment of COVID‑19 requiring hospitalization.[146] The FDA issued an emergency use authorization (EUA) for the combination of baricitinib with remdesivir, for the treatment of suspected or laboratory confirmed COVID-19 in hospitalized people two years of age or older requiring supplemental oxygen, invasive mechanical ventilation, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO).[147] In early March, President Trump directed the FDA to test certain medications to discover if they had the potential to treat COVID-19 patients.[148] Among those were chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, which have been successfully used to treat malaria for over fifty years. A small test in France by researcher Didier Raoult had given positive results, although the study was criticized for design flaws, small sample size, and the fact that it was published before peer review.[149] On March 28, the FDA issued an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) which allowed certain hospitalized COVID-19 patients to be treated with hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine.[150][148][151][152] On June 15, the FDA revoked the EUA for hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine as potential treatments for COVID-19, saying the available evidence showed "no benefit for decreasing the likelihood of death or speeding recovery".[153] However, Trump continued to promote the use of hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19 by late July.[154]

From early 2020, more than 70 companies worldwide (with five or six operating primarily in the U.S.) began vaccine research.[155][156] In preparation for large-scale production, Congress set aside more than $3.5 billion for this purpose as part of the CARES Act.[157][156] On November 20, 2020, the Pfizer–BioNTech partnership submitted a request for emergency use authorization for its vaccine to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA),[158][159] which was granted on December 11.[160][161] On December 18, 2020, the FDA granted the Moderna vaccine emergency use authorization,[162][163] which Moderna had requested on November 30, 2020.[164][165] Starting on December 14, 2020, the first doses of COVID-19 vaccine were administered.[166]

Polling showed a significant partisan divide regarding the outbreak.[167] In February, similar numbers of Democrats and Republicans believed COVID-19 was "a real threat": 70% and 72%, respectively. By mid-March, 76% of Democrats viewed COVID-19 as "a real threat", while only 40% of Republicans agreed.[168] In mid-March, various polls found Democrats were more likely than Republicans to believe "the worst was yet to come" (79–40%), to believe their lives would change in a major way due to the outbreak (56–26%),[169] and to take certain precautions against the virus (83–53%).[170] The CDC was the most trusted source of information about the outbreak (85%), followed by the WHO (77%), state and local government officials (70–71%), the news media (47%), and Trump (46%).[170] A May 2020 poll concluded that 54% of people in the U.S. felt the federal government was doing a poor job in stopping the spread of COVID-19 in the country. 57% felt the federal government was not doing enough to address the limited availability of COVID-19 testing. 58% felt the federal government was not doing enough to prevent a second wave of COVID-19 cases later in 2020.[171] In September 2020, Pew Research Center found that the global image of the United States had suffered in many foreign nations. In some nations, the United States' favorability rating had reached a record low since Pew began collecting this data nearly twenty years ago. Across thirteen different nations, a median of fifteen percent of respondents rated the U.S. response to the pandemic positively.[172]

Impacts

Economic

The pandemic, along with the resultant stock market crash and other impacts, led a recession in the United States following the economic cycle peak in February 2020.[173] The economy contracted 4.8 percent from January through March 2020,[174] and the unemployment rate rose to 14.7 percent in April.[175] The total healthcare costs of treating the epidemic could be anywhere from $34 billion to $251 billion according to analysis presented by The New York Times.[176] A study by economists Austan Goolsbee and Chad Syverson indicated that most economic impact due to consumer behavior changes was prior to mandated lockdowns.[177] During the second quarter of 2020, the U.S. economy suffered its largest drop on record, with GDP falling at an annualized rate of 32.9 percent. As of June 2020, the U.S. economy was over ten percent smaller than it was in December 2019.[178]

In September, Bain & Company reported on the tumultuous changes in consumer behavior before and during the pandemic. Potentially permanently, they found acceleration towards e-commerce, online primary healthcare, livestreamed gym workouts, and moviegoing via subscription television. Concurrent searches for both low-cost and premium products, and a shift to safety over sustainability, occurred alongside rescinded bans and taxes on single-use plastics, and losses of three to seven years of gains in out-of-home foodservice.[179] OpenTable estimated in May that 25 percent of American restaurants would close their doors permanently.[180]

The economic impact and mass unemployment caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has raised fears of a mass eviction crisis,[181][182][183][184] with an analysis by the Aspen Institute indicating 30–40 million are at risk for eviction by the end of 2020.[185][186] According to a report by Yelp, about sixty percent of U.S. businesses that have closed since the start of the pandemic will stay shut permanently.[187]

| Variable | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | June | July | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jobs, level (000s)[188] | 152,463 | 151,090 | 130,303 | 133,002 | 137,802 | 139,582 | 140,914 | 141,720 | 142,373 | 142,629 |

| Jobs, monthly change (000s)[188] | 251 | −1,373 | −20,787 | 2,699 | 4,800 | 1,780 | 1,371 | 661 | 653 | 256 |

| Unemployment rate %[189] | 3.5% | 4.4% | 14.7% | 13.3% | 11.1% | 10.2% | 8.4% | 7.9% | 6.9% | 6.7% |

| Number unemployed (millions)[190] | 5.8 | 7.1 | 23.1 | 21.0 | 17.8 | 16.3 | 13.6 | 12.6 | 11.1 | 10.7 |

| Employment to population ratio %, age 25–54[191] | 80.5% | 79.6% | 69.7% | 71.4% | 73.5% | 73.8% | 75.3% | 75.0% | 76.0% | 76.0% |

| Inflation rate % (CPI-All)[192] | 2.3% | 1.5% | 0.4% | 0.2% | 0.7% | 1.0% | TBD | TBD | TBD | TBD |

| Stock market S&P 500 (avg. level)[193] | 3,277 | 2,652 | 2,762 | 2,920 | 3,105 | 3,230 | 3,392 | 3,380 | 3,270 | 3,694 |

| Debt held by public ($ trillion)[194] | 17.4 | 17.7 | 19.1 | 19.9 | 20.5 | 20.6 | 20.8 | 21.0 | 21.2 | 21.3 |

Social

The pandemic has had far-reaching consequences beyond the disease itself and efforts to contain it, including political, cultural, and social implications.

From the earliest days of the pandemic, there were reported incidents of xenophobia and racism against Asian Americans.[31] During the first year, an ad-hoc organization called Stop AAPI Hate received 3,795 reports of racism against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders.[195]

Disproportionate numbers of cases have been observed among Black and Latino populations.[26][27][28] Of four studies published in September 2020, three found clear disparities due to race and the fourth found slightly better survival rates for Hispanics and Blacks.[196] As of September 15, 2020, Blacks had COVID-19 mortality rates more than twice as high as the rate for Whites and Asians, who have the lowest rates.[197] CNN reported in May 2020 that the Navajo Nation had the highest rate of infection in the United States.[198] In June 2021, the CDC confirmed these numbers, reporting that American Indian or Alaska Native, Non-Hispanic persons had the highest rates of both hospitalizations and deaths, while Hispanic and Latino persons suffered the highest rates of COVID compared to White persons. However the CDC noted that only 61% of case reports included race and ethnicity data, which could result in inaccurate estimates of the relative risk among groups. [199] Additionally, a study published by the New England Journal of Medicine in July 2020 revealed that the effect of stress and weathering on minority groups decreases their stamina against COVID.[200]

From 2019 to 2020 in the United States, the life expectancy of a Hispanic American decreased 3 years, for an African American 2.9 years, and for a White American 1.2 years.[12] The COVID Tracking Project[201] published data revealing that people of color were contracting and dying from COVID-19 at higher rates than Whites. An NPR analysis of April–September 2020 data from the COVID Tracking Project found that Black people's share of COVID-19 deaths across the United States was 1.5 times greater (in some states 2.5 times greater) than their share of the U.S. population. Similarly, Hispanics and Latinos were disproportionately infected in 45 states and had a disproportionate share of the deaths in 19 states. Native American and Alaskan Native cases and deaths were disproportionally high in at least 21 states and, in some, as much as five times more than average. White non-Hispanics died at a lower rate than their share of the population in 36 states and D.C.[202]

By April 2020, closed schools affected more than 55 million students.[203]

Elections

The pandemic prompted calls from voting rights groups and some Democratic Party leaders to expand mail-in voting, while Republican leaders generally opposed the change. Some states were unable to agree on changes, resulting in lawsuits. Responding to Democratic proposals for nationwide mail-in voting as part of a coronavirus relief law, President Trump said "you'd never have a Republican elected in this country again" despite evidence the change would not favor any particular group.[204] Trump called mail-in voting "corrupt" and said voters should be required to show up in person, even though, as reporters pointed out, he had himself voted by mail in the last Florida primary.[205] Though mail-in vote fraud is slightly higher than in-person voter fraud, both instances are rare, and mail-in voting can be made more secure by disallowing third parties to collect ballots and providing free drop-off locations or prepaid postage.[206]

High COVID-19 fatalities at the state and county level correlated with a drop in expressed support for the election of Republicans, including the reelection of Trump, according to a study published in Science Advances that compared opinions in January–February 2020 with opinions in June 2020.[207]

Vaccination campaign

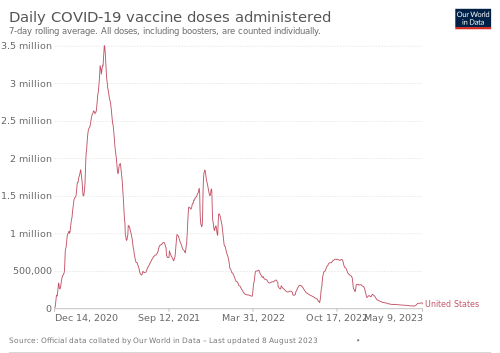

| Timeline of daily COVID-19 vaccine doses administered in the US.[208] |

|

| See the latest date on the timeline at the bottom. |

United States. Percentage with at least one vaccination dose. See Commons source for date of last upload. US territories: GU = Guam. AS = American Samoa. RP = Republic of Palau. FM = Federated States of Micronesia. MP = Northern Mariana Islands. MH = Marshall Islands. VI = Virgin Islands.[209] | |

| Date | December 14, 2020 – present |

|---|---|

| Location | Compact of Free Association:[210][211] |

| Cause | COVID-19 pandemic in the United States |

| Organized by | Center for Disease Control and Prevention |

| Participants | 182,896,080 people have received at least one dose administered of Pfizer–BioNTech, Moderna and Janssen (July 7, 2021) 157,908,171 people have been fully vaccinated (both doses of Pfizer–BioNTech or Moderna, or one dose of Johnson & Johnson)[212] |

| Outcome | 55% of the United States population has received at least one dose of a vaccine

48% of the United States population is fully vaccinated |

| Website | COVID-19 Vaccine: CDC |

The COVID-19 vaccination campaign in the United States is an ongoing mass immunization campaign for the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. The FDA granted emergency use authorization to the Pfizer–BioNTech vaccine on December 10, 2020;[213] mass vaccinations began on December 14, 2020. The Moderna vaccine was granted emergency use authorization on December 17, 2020,[214] and the Janssen (Johnson & Johnson) vaccine was granted emergency use authorization on February 27, 2021.[215] By April 19, 2021, all U.S. states had opened vaccine eligibility to residents aged 16 and over.[216] On May 10, 2021, the FDA approved the Pfizer vaccine for adolescents aged 12 to 15.[217] On August 23, 2021, the FDA granted full approval to the Pfizer–BioNTech vaccine for individuals aged 16 and over.[218]

The U.S. government first initiated the campaign under the presidency of Donald Trump with Operation Warp Speed, a public–private partnership to expedite the development and manufacturing of COVID-19 vaccines. Joe Biden became the new President of the United States on January 20, 2021. Biden began his term with an immediate goal of administering 100 million vaccine doses within his first hundred days in office, signing an executive order which included increasing supplies for vaccination.[219][220][221] This goal was met on March 19, 2021.[222] On March 25, 2021, he announced he would increase the goal to 200 million within his first 100 days in office.[223] This goal was eventually reached on April 21, 2021.[224]

By July 4, 2021, 67% of the United States' adult population had received at least one dose, just short of a goal of 70%. This goal was eventually met on August 2, 2021. While vaccines have helped significantly reduce the number of new COVID-19 infections nationwide, states with below-average vaccination rates began to see increasing numbers of cases credited to the highly infectious Delta variant by July 2021, which led to an increased push by organizations and companies to begin mandating that their employees be vaccinated for COVID-19.Vaccine mandates

With the final approval by the FDA of a vaccine, President Biden has appealed to public organizations and private companies to require employees to be vaccinated, which companies are now legally allowed to do.[225]

Until recently, many companies were giving bonuses for getting vaccinated.[226] Nonetheless, nearly 2,000 private hospitals and health systems had previously issued vaccine mandates. Many companies outside health care did the same, such as United Airlines, Tyson Foods, and Walmart among them. Washington state had already required vaccines for all state employees and contractors.[226] With the new Delta variant spreading infections more quickly due to its higher transmissibility, companies including Facebook, Google, and Salesforce, have already issued employee vaccine mandates.[227]

According to a USA Today poll, 68% supported a business's right to refuse service to unvaccinated customers, and 62% supported employer's right to mandate vaccinations to its employees. In the same poll, 72% also felt that mandating masks was "a matter of health and safety" and should not be considered an infringement on personal liberty.[228]

Preparations made after previous outbreaks

The United States has experienced pandemics and epidemics throughout its history, including the 1918 Spanish flu, the 1957 Asian flu, and the 1968 Hong Kong flu pandemics.[229][230][231] In the most recent pandemic prior to COVID-19, the 2009 swine flu pandemic took the lives of more than 12,000 Americans and hospitalized another 270,000 over the course of approximately a year.[229]

According to the Global Health Security Index, an American-British assessment which ranks the health security capabilities in 195 countries, the U.S. was the "most prepared" nation in 2020.[232][233]

Statistics

The CDC publishes official numbers of COVID-19 cases in the United States.

In February 2020, at the beginning of the pandemic, a shortage of tests made it impossible to confirm all possible COVID-19 cases[234][235] and resulting deaths, so the early numbers were likely undercounts.[236][237][238][239] Another way to estimate COVID-19 deaths that includes unconfirmed cases is to use the excess mortality, which is the overall number of deaths that exceed what would normally be expected.[240] From March 1, 2020 through the end of 2020, there were 522,368 excess deaths in the United States, which is 22.9% more than would have been expected in that time period.[241] The CDC estimates that, between February 2020 and May 2021, only 1 in 1.3 COVID-19 deaths were attributed to COVID-19,[242] and the true COVID-19 death toll was 767,000 as of May 2021.[243]See also

- COVID Tracking Project

- COVID-19 pandemic by country and territory

- COVID-19 pandemic in North America

- Misinformation related to the COVID-19 pandemic

- Statistics of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States

- United States House Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis

- United States influenza statistics by flu season

Notes

- ^ A lack of mass testing obscured the extent of the outbreak.[18]

- ^ Examples of areas in which clusters have occurred include urban areas, nursing homes, long-term care facilities, group homes for the intellectually disabled,[32] detention centers (including prisons), meatpacking plants, churches, and navy ships.[33]

- ^ This chart only includes lab-confirmed cases and deaths. Not all states report recoveries. Data for the current day may be incomplete.

- ^ The editorial board for The Wall Street Journal suggested the world may have been "better prepared" had the PHEIC been declared a week sooner, when the virus had spread to other countries.[43]

- ^ In a news release, Sean Conley, physician to President Trump, incorrectly identified Regeneron's monoclonal antibody product as polyclonal.[88]

References

- ^ Sheikh K, Rabin RC (March 10, 2020). "The Coronavirus: What Scientists Have Learned So Far". The New York Times. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ "Coronavirus: the first three months as it happened". Nature. April 22, 2020. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-00154-w. PMID 32152592. S2CID 212652777.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Holshue ML, DeBolt C, Lindquist S, Lofy KH, Wiesman J, Bruce H, et al. (March 2020). "First Case of 2019 Novel Coronavirus in the United States". New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (10): 929–936. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2001191. PMC 7092802. PMID 32004427.

- ^ "Second Travel-related Case of 2019 Novel Coronavirus Detected in United States". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Second Travel-related Case of 2019 Novel Coronavirus Detected in United States: The patient returned to the U.S. from Wuhan on January 13, 2020

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Cases in U.S." Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). March 28, 2020. Updated, one day after other sources.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Coronavirus COVID-19 (2019-nCoV)" (ArcGIS). Johns Hopkins CSSE. Frequently updated.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Estimated COVID-19 Burden". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). July 27, 2021. Retrieved August 11, 2021.

- ^ "U.S. recovered COVID-19 cases". Worldometer. Frequently updated.

- ^ "Mortality Analyses". Johns Hopkins University. Retrieved December 17, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Nedelman M (April 29, 2021). "More than a third of the US has been infected with Covid-19, CDC estimates". CNN. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ^ Stobbe M (December 21, 2020). "US deaths in 2020 top 3 million, by far most ever counted". Associated Press. Retrieved December 22, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bosman J, Kasakove S, Victor D (July 21, 2021). "U.S. Life Expectancy Plunged in 2020, Especially for Black and Hispanic Americans". The New York Times. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ Aubrey A (January 31, 2020). "Trump Declares Coronavirus A Public Health Emergency And Restricts Travel From China". NPR. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

'Foreign nationals other than immediate family of U.S. citizens and permanent residents who have traveled in China in the last 14 days will be denied entry into United States,' Azar said.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Robertson L (April 15, 2020). "Trump's Snowballing China Travel Claim". FactCheck.org. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

... effective February 2.

- ^ Lemire J, Miller Z, Colvin J, Alonso-Zaldivar R (April 12, 2020). "Signs missed and steps slowed in Trump's pandemic response". Associated Press. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- ^ Pilkington E, McCarthy T (March 28, 2020). "The missing six weeks: how Trump failed the biggest test of his life". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved March 28, 2020.

- ^ Ollstein AM (April 14, 2020). "Trump halts funding to World Health Organization". Politico. ISSN 2381-1595. Wikidata Q104180080. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- ^ Whoriskey P, Satija N (March 16, 2020). "How U.S. coronavirus testing stalled: Flawed tests, red tape and resistance to using the millions of tests produced by the WHO". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ^ Watson K (March 27, 2020). "Trump invokes Defense Production Act to require GM to produce ventilators". CBS News. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- ^ "COVID-19 Cases Are Skyrocketing, But Deaths Are Flat – So Far. These 5 Charts Explain Why". Time. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

- ^ Elamroussi A, Gumbrecht J, Levenson E (August 15, 2021). "US could soon hit more than 200,000 new coronavirus cases per day, NIH director warns". CNN. Retrieved August 15, 2021.

- ^ "FDA Approves First COVID-19 Vaccine", FDA, August 23, 2021

- ^ Stieg C (July 6, 2021). "Dr. Fauci: Where to expect new Covid surges in the U.S.—and what it means for mask-wearing, other restrictions". CNBC. Retrieved July 11, 2021.

- ^ "Fauci: Polio would still exist in US if 'false information' being spread now existed decades ago", ABC News, July 20, 2021

- ^ Jump up to: a b Deb S, Cacciola S, Stein M (March 11, 2020). "Sports Leagues Bar Fans and Cancel Games Amid Coronavirus Outbreak". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Godoy M (May 30, 2020). "What Do Coronavirus Racial Disparities Look Like State By State?". NPR.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Karson K, Scanlan Q (May 22, 2020). "Black Americans and Latinos nearly 3 times as likely to know someone who died of COVID-19: Poll". ABC News.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "States tracking COVID-19 race and ethnicity data". American Medical Association. July 28, 2020. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- ^ Beleche T, et al. (May 2021). "COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy: Demographic Factors, Geographic Patterns, and Changes Over Time" (PDF). Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, US HHS. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- ^ Livingston C (April 8, 2021). "Black Americans' Vaccine Hesitancy is Grounded in More Than Mistrust". Duke University. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tavernise S, Oppel Jr RA (March 23, 2020). "Spit On, Yelled At, Attacked: Chinese-Americans Fear for Their Safety". The New York Times. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- ^ "COVID-19 Infections And Deaths Are Higher Among Those With Intellectual Disabilities". NPR.

- ^ "U.S. Navy Policies Battling COVID-19 Rely Heavily On Isolation". NPR.

- ^ Margolin J, Meek JG (April 8, 2020). "Intelligence report warned of coronavirus crisis as early as November: Sources". ABC News. Retrieved December 6, 2020.

- ^ Diaz J (December 1, 2020). "Coronavirus Was In U.S. Weeks Earlier Than Previously Known, Study Says". NPR. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ "Outbreak of Pneumonia of Unknown Etiology (PUE) in Wuhan, China". CDC. January 8, 2020.

- ^ Kuo L (January 21, 2020). "China confirms human-to-human transmission of coronavirus". The Guardian. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- ^ "CDC Emergency Operations Center Activations". CDC. January 20, 2020.

- ^ Althoff KN, Schlueter DJ, Anton-Culver H, Cherry J, Denny JC, Thomsen I, et al. (June 2021). "Antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 in All of Us Research Program Participants, January 2-March 18, 2020". Clinical Infectious Diseases. doi:10.1093/cid/ciab519. PMID 34128970.

- ^ "Timeline: WHO's COVID-19 response". World Health Organization. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- ^ Boseley S (January 30, 2020). "WHO declares coronavirus a global health emergency". The Guardian. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- ^ Kennedy M (January 30, 2020). "WHO Declares Coronavirus Outbreak A Global Health Emergency". NPR. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- ^ "World Health Coronavirus Disinformation". The Wall Street Journal. April 5, 2020. Archived from the original on April 9, 2020. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ Wayland M (January 30, 2020). "Trump says coronavirus outbreak is 'all under control' and a 'very small problem' in US". CNBC (NBCUniversal). Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "US declares public health emergency from coronavirus". The Boston Globe. February 1, 2020.

- ^ Diamond D (January 28, 2021). "U.S. handling of American evacuees from Wuhan increased coronavirus risks, watchdog finds". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 7, 2021. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- ^ Moon S (April 24, 2020). "A seemingly healthy woman's sudden death is now the first known US coronavirus-related fatality". CNN. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

- ^ Debolt D (April 25, 2020). "29 people had flu-like symptoms when they died in Santa Clara County. Nine tested positive for coronavirus". The Mercury News. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ Melinek J (May 1, 2020). "When Did COVID-19 Arrive and Could We Have Spotted It Earlier?". MedPage Today. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- ^ Taylor M (March 23, 2020). "Exclusive: U.S. axed CDC expert job in China months before virus outbreak". Reuters. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ Schuchat A (May 2020). "Public Health Response to the Initiation and Spread of Pandemic COVID-19 in the United States, February 24 – April 21, 2020" (PDF). MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 69 (18): 551–556. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6918e2. PMC 7737947. PMID 32379733.

- ^ "Lawrence Garbuz, New York's First Known COVID-19 Case, Reveals What He Learned About Attorney Well-Being From the Virus". New York State Bar Association. August 11, 2020.

- ^ Brody L (March 6, 2021). "Covid-19's 'Patient Zero' in New York: What Life Is Like for the New Rochelle Lawyer". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ "New York area's 'patient zero' says coronavirus 'wasn't on my mind' when he got sick". NBC News.

- ^ Santucci J (February 27, 2020). "What we know about the White House coronavirus task force now that Mike Pence is in charge". USA Today. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- ^ "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Summary". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). March 7, 2020. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- ^ "Coronavirus Has Become a Pandemic, W.H.O. Says". The New York Times. March 11, 2020.

- ^ "Dr. Anthony Fauci addresses COVID-19 mortality rate". C-SPAN. March 11, 2020. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

- ^ Taylor A, Armus T (March 11, 2020). "Live updates: As U.S. coronavirus cases top 1,000, mixed signs of recovery in China, South Korea". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 11, 2020.

- ^ Liptak K (March 16, 2020). "White House advises public to avoid groups of more than 10, asks people to stay away from bars and restaurants". CNN. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ^ "Global Level 4 Health Advisory – Do Not Travel". travel.state.gov.

- ^ "The 4 Key Reasons the U.S. Is So Behind on Coronavirus Testing". The Atlantic. March 15, 2020.

- ^ "They were supposed to build stages for Coachella. Now they're building coronavirus triage tents". Los Angeles Times. March 30, 2020.

- ^ Norwood C (April 3, 2020). "Most states have issued stay-at-home orders, but enforcement varies widely". PBS. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- ^ Chan C, Shumaker L, Maler S (March 28, 2020). "Confirmed coronavirus cases in U.S. reach 100,000: Reuters tally". Reuters. Retrieved March 28, 2020.

- ^ "Trump wants masks on all nursing home workers, temperature checks for all, and separate COVID-19 units". McKnight's Long-term Care News. April 3, 2020.

- ^ "U.S. coronavirus deaths top 20,000, highest in world exceeding Italy: Reuters tally". Reuters. April 11, 2020. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- ^ "Trump Administration Announces New Nursing Homes COVID-19 Transparency Effort". Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. April 19, 2020.

- ^ Steve Almasy; Christina Maxouris; Nicole Chavez. "US coronavirus cases surpass 1 million and the death toll is greater than US losses in Vietnam War". CNN. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ Fisher M (May 27, 2020). "U.S. coronavirus death toll surpasses 100,000, exposing nation's vulnerabilities". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- ^ Noori AF, et al. (June 11, 2020). "U.S. surpasses 2 million coronavirus cases". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- ^ Joseph A (July 21, 2020). "Actual Covid-19 case count could be 6 to 24 times higher than official estimates, CDC study shows". statnews. Stat. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- ^ Havers FP, Reed C, Lim T, Montgomery JM, Klena JD, Hall AJ, et al. (July 2020). "Seroprevalence of Antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 in 10 Sites in the United States, March 23-May 12, 2020". JAMA Internal Medicine. 180 (12): 1576. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.4130. ISSN 2168-6106. PMID 32692365.

- ^ DeVille T. "Almost 17 million U.S. coronavirus cases were not detected during first half of 2020, study led by UMBC graduate finds". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved March 19, 2021.

- ^ "Briefing on the U.S. Government's Next Steps With Regard to Withdrawal From the World Health Organization". US Department of State. September 2, 2020. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- ^ "COVID-19 Pandemic Planning Scenarios" (PDF). CDC. July 10, 2020. Retrieved September 29, 2020.

- ^ Durkee A (July 24, 2020). "Medical Experts Tell Government: 'Shut It Down Now, And Start Over'". Forbes Media. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ Board E (August 8, 2020). "America Could Control the Pandemic by October. Let's Get to It". The New York Times. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ Rivers C, Martin E, Watson C, Schoch-Spana M, Cicero A, Inglesby T (2020). "Resetting Our Response: Changes Needed in the US Approach to COVID-19". Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security. and Benito M (July 23, 2020). "Back to normal by October? Dr. Hotez sends the White House a national, unified coronavirus plan". KHOU-TV. and Osterholm MT, Kashkari N (August 7, 2020). "Here's How to Crush the Virus Until Vaccines Arrive". The New York Times. and Slavitt A (August 4, 2020). "Joe Biden is the national reset we need on COVID-19, but he's more than 75,000 lives away". USA Today. and Branswell H (August 10, 2020). "Winter is coming: Why America's window of opportunity to beat back Covid-19 is closing". STAT. Retrieved August 11, 2020.

- ^ Walker M, Healy J (November 6, 2020). "A Motorcycle Rally in a Pandemic? 'We Kind of Knew What Was Going to Happen'". The New York Times. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- ^ Firestone MJ, Wienkes H, Garfin J, Wang X, Vilen K, Smith KE, et al. (November 2020). "COVID-19 Outbreak Associated with a 10-Day Motorcycle Rally in a Neighboring State – Minnesota, August–September 2020" (PDF). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 69 (47): 1771–1776. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6947e1. PMC 8022865. PMID 33237891. S2CID 227176504.

- ^ Craft D (August 8, 2020). "U.S. sets record as coronavirus cases top 5 million". Reuters. Retrieved September 25, 2020.

- ^ Chappel B (September 22, 2020). "'Enormous And Tragic': U.S. Has Lost More Than 200,000 People To COVID-19". NPR. Retrieved September 22, 2020.

- ^ Haberman M, Shear MD (October 1, 2020). "Trump Says He'll Begin 'Quarantine Process' After Hope Hicks Tests Positive for Coronavirus". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Moreno JE (October 2, 2020). "White House wanted to keep Hope Hicks's positive COVID-19 test private: report". The Hill. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ Dawsey J, Itkowitz C. "Trump says he and first lady have tested positive for coronavirus". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved October 2, 2020.

- ^ Manke K (October 6, 2020). "Trump's COVID-19 treatments suggest severe illness, UC Berkeley expert says". UC Berkeley News. Retrieved October 7, 2020.

- ^ "Memorandum From Trump's Doctor on COVID-19 Treatment". US News & World Report. Associated Press. October 2, 2020. Retrieved October 8, 2020. and Cohen J (October 5, 2020). "Update: Here's what is known about Trump's COVID-19 treatment". Science. doi:10.1126/science.abf0974.

- ^ Liptak K (October 3, 2020). "Trump taken to Walter Reed medical center and will be hospitalized 'for the next few days'". CNN. Retrieved February 24, 2021.

- ^ Cha AE, Goldstein A (October 4, 2020). "Prospect of Trump's early hospital discharge mystifies doctors". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- ^ Mansfield E, Salman J, Voyles Pulver D (October 22, 2020). "Trump's campaign made stops nationwide. Coronavirus cases surged in his wake in at least five places". USA Today. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ Facher L (November 9, 2020). "Biden transition team unveils members of Covid-19 task force". Stat. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- ^ Wang C (November 9, 2020). "U.S. coronavirus cases cross 10 million as outbreaks spike across the nation". CNBC. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- ^ "10 Million People Have Tested Positive for Coronavirus in the United States". Time. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- ^ "Pfizer says COVID-19 vaccine is looking 90% effective". Associated Press. November 9, 2020. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- ^ Thomas K, Gelles D, Zimmer C (November 9, 2020). "Pfizer's Early Data Shows Vaccine Is More Than 90% Effective". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- ^ Alonso-Zalidivar R (November 12, 2020). "Feds announce COVID-19 vaccine agreement with drug stores". Associated Press. Retrieved November 18, 2020.

- ^ O'Brien M (November 23, 2020). "Many Americans flying for Thanksgiving despite CDC pleas". The Republican. Archived from the original on February 6, 2021. Retrieved November 27, 2020.

- ^ Bacon J, Aspegren E, Hauck G (December 8, 2020). "Coronavirus updates: Joe Biden pledges to deliver 100M doses in 100 days; US reaches 15M infections; Ohio-State Michigan football game off". USA Today. Retrieved December 8, 2020.

- ^ Yan H (December 14, 2020). "Covid-19 now kills more than 1 American every minute. And the rate keeps accelerating as the death toll tops 300,000". CNN. Retrieved December 14, 2020.

- ^ Murphy M (December 24, 2020). "U.S. to require all air passengers arriving from U.K. to test negative for COVID-19". MarketWatch. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- ^ Tufekci Z (December 31, 2020). "The Mutated Virus Is a Ticking Time Bomb". The Atlantic. Retrieved January 5, 2021.

- ^ "US reports its first known case of new UK Covid variant". The Guardian. December 29, 2020. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ Cohen L (January 1, 2021). "U.S. surpasses 20 million cases of coronavirus on first day of 2021". CBS News. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ Lim D (January 1, 2021). "U.S. coronavirus cases eclipse 20 million". Politico. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ Nedelman M (January 6, 2021). "CDC has found more than 50 US cases of coronavirus variant first identified in UK". CNN. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ Reimann N (January 8, 2021). "'Close To A Worst-Case Scenario' – Former CDC Director Issues 'Horrifying' Outlook For New Covid Strain". Forbes. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- ^ Geddes L, Holpuch A (January 1, 2021). "New coronavirus variant may have been in US since October". The Guardian. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ Stone W (January 19, 2021). "As Death Rate Accelerates, U.S. Records 400,000 Lives Lost To The Coronavirus". NPR. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ Tompkins L (January 22, 2021). "U.S. coronavirus cases top 25 million". The New York Times. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ Yeung J, McKeehan B. "More than 2,750 cases of coronavirus variants reported in the US". CNN. Retrieved March 5, 2021.

- ^ Sullivan S. "Biden directs states to make all adults eligible for vaccine by May 1". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved March 12, 2021.

- ^ Maan A (March 24, 2021). "U.S. COVID-19 cases top 30 million as states race to vaccinate". Reuters. Retrieved March 24, 2021.

- ^ Cullinane S (March 27, 2021). "Record Covid-19 vaccinations don't mean it's time to relax, officials say". Cnn.com. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

ABC.UKDominantwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Haseltine WA (April 12, 2021). "An Indian SARS-CoV-2 Variant Lands In California. More Danger Ahead?". Forbes. USA. Retrieved April 20, 2021.

- ^ Maxouris C (April 25, 2021). "Some parts of the US are more vulnerable to another hit by coronavirus. Here's why". CNN. Retrieved April 25, 2021.

- ^ Maxouris C (April 18, 2021). "Covid-19 vaccine demand is slowing in parts of the US. Now an uphill battle starts to get more shots into arms". CNN. Retrieved April 25, 2021.

- ^ Savidge M, Barajas A, Waldrop T (April 23, 2021). "Vaccine hesitancy in Hinds County, Mississippi, is a story shared elsewhere". CNN. Retrieved April 25, 2021.

- ^ Groppe M (May 4, 2021). "Biden's new goal: 70% of adults at least partially vaccinated by July 4". USA Today. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- ^ Bebinger M, Farmer B (July 5, 2021). "As COVID Vaccinations Slow, Parts Of The U.S. Remain Far Behind 70% Goal". NPR. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ Sullivan B (May 6, 2021). "New Study Estimates More Than 900,000 People Have Died Of COVID-19 In U.S." NPR. Retrieved May 11, 2021.

- ^ Bowden J (May 9, 2021). "Fauci: 'No doubt' US has undercounted COVID-19 deaths". The Hill. Retrieved May 11, 2021.

- ^ Lovelace Jr B (May 13, 2021). "CDC says fully vaccinated people don't need to wear face masks indoors or outdoors in most settings". CNBC. Retrieved May 26, 2021.

- ^ Bursztynsky J (May 16, 2021). "CDC director defends telling fully vaccinated they can go without masks amid confusion in states, cities". CNBC. Retrieved May 26, 2021.

- ^ Har J, Kunzelman M (June 15, 2021). "US COVID-19 deaths hit 600,000, equal to yearly cancer toll". Associated Press. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- ^ Soucheray S (June 29, 2021). "US COVID-19 cases rise, likely due to Delta variant". CIDRAP. Retrieved July 11, 2021.

- ^ Lovelace B Jr (July 7, 2021). "CDC data shows highly transmissible delta variant is now the dominant Covid strain in the U.S." CNBC. Retrieved July 11, 2021.

- ^ Holcombe M, Waldrop T (July 20, 2021). "More infectious Delta variant makes up 83% of new US coronavirus cases as vaccine hesitancy persists". CNN. Retrieved July 20, 2021.

- ^ Johnson A (August 1, 2021). "U.S. passes 35 million Covid cases as California tops 4 million". NBC News. Retrieved August 4, 2021.

- ^ There are only 8 ICU beds available in the entire state of Arkansas as COVID-19 spikes

- ^ Louisiana hospitals, overwhelmed with Covid patients, sending ambulances to Texas

- ^ Facing a crush of COVID-19 patients, ICUs are completely full in at least 50 Texas hospitals

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Hospitals Face A Shortage Of Nurses As COVID Cases Soar

- ^ As COVID-19 Surges, Mississippi Hospital 'Days Away' From Turning Away Patients

- ^ Caldwell T (August 13, 2021). "These 8 states make up half of US Covid-19 hospitalizations. And the surge among the unvaccinated is overwhelming health care workers". CNN. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- ^ Farber M (January 28, 2020). "China spurned CDC offer to send a team to help contain coronavirus: US Health Secretary". Fox News.

- ^ Allyn B (February 8, 2020). "China's Coronavirus Death Toll Surpasses SARS Pandemic". NPR. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ "C.D.C. and W.H.O. Offers to Help China Have Been Ignored for Weeks". The New York Times. February 7, 2020.

- ^ "Boeing donating 250,000 medical masks to battle coronavirus in China". KOMO-TV. January 29, 2020.

- ^ "The United States Announces Assistance To Combat the Novel Coronavirus". U.S. Dept. of State. February 7, 2020.

- ^ Guzman J (February 7, 2020). "US pledges $100 million to help fight coronavirus in China". The Hill. Retrieved April 11, 2020.

- ^ "Contact tracing may help avoid another lockdown. Can it work in the U.S.?". May 29, 2020.

- ^ Cunningham PW (June 15, 2020). "Analysis | The Health 202: U.S. isn't ready for the contact tracing it needs to stem the coronavirus". The Washington Post.

- ^ "New Contact Tracing Apps Need Access To Users' Private Data To Control Spread Of COVID-19". KPIX-TV. July 1, 2020. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- ^ Commissioner Oo (October 22, 2020). "FDA Approves First Treatment for COVID-19". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ "Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Authorizes Drug Combination for Treatment of COVID-19". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). November 23, 2020. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "U.S. Moves to Expand Array of Drug Therapies Deployed Against Coronavirus". The Wall Street Journal. March 19, 2020.

- ^ Braun E (March 30, 2020). "In France, controversial doctor stirs coronavirus debate". Politico. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

- ^ "Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: Daily Roundup March 30, 2020". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). March 30, 2020. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

- ^ Koppock K (March 13, 2020). "FDA Announces Two Drugs Given 'Compassionate Use' Status in Treating COVID-19". Pharmacy Times. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- ^ Wise J (March 30, 2020). "FDA issues emergency-use authorization for anti-malaria drugs amid coronavirus outbreak". The Hill. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- ^ Research Cf (June 26, 2020). "FDA cautions against use of hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine for COVID-19 outside of the hospital setting or a clinical trial due to risk of heart rhythm problems". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

- ^ Gittleson B, Phelps J, Cathey L (July 28, 2020). "Trump doubles down on defense of hydroxychloroquine to treat COVID-19 despite efficacy concerns". ABC News. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

- ^ "COVID-19 (coronavirus) vaccine: Get the facts". Mayo Clinic. April 22, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gottlieb S (April 26, 2020). "America Needs to Win the Coronavirus Vaccine Race". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ "Guide to the Cares Act". United States Senate Committee on Small Business and Entrepreneurship. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- ^ "Pfizer and BioNTech to Submit Emergency Use Authorization Request Today to the U.S. FDA for COVID-19 Vaccine". Pfizer (Press release). November 20, 2020. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ Park A (November 20, 2020). "Exclusive: Pfizer CEO Discusses Submitting the First COVID-19 Vaccine Clearance Request to the FDA". Time. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ "FDA Takes Key Action in Fight Against COVID-19 By Issuing Emergency Use Authorization for First COVID-19 Vaccine" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). December 11, 2020. Retrieved December 11, 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Oliver SE, Gargano JW, Marin M, Wallace M, Curran KG, Chamberland M, et al. (December 2020). "The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices' Interim Recommendation for Use of Pfizer–BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine – United States, December 2020" (PDF). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 69 (50): 1922–1924. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6950e2. PMC 7745957. PMID 33332292.

- ^ "FDA Takes Additional Action in Fight Against COVID-19 By Issuing Emergency Use Authorization for Second COVID-19 Vaccine". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). Retrieved December 18, 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Oliver SE, Gargano JW, Marin M, Wallace M, Curran KG, Chamberland M, et al. (December 2020). "The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices' Interim Recommendation for Use of Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine – United States, December 2020" (PDF). MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 69 (5152): 1653–1656. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm695152e1. PMID 33382675. S2CID 229945697.

- ^ "Moderna Applies for Emergency F.D.A. Approval for Its Coronavirus Vaccine". The New York Times. November 30, 2020. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

- ^ "Moderna Announces Primary Efficacy Analysis in Phase 3 COVE Study for Its COVID-19 Vaccine Candidate and Filing Today with U.S. FDA for Emergency Use Authorization". Moderna, Inc. (Press release). November 30, 2020. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

- ^ Pereira I (December 14, 2020). "US administers 1st doses of Pfizer coronavirus vaccine". ABC News. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- ^ Aleem Z (March 15, 2020). "A new poll shows a startling partisan divide on the dangers of the coronavirus". Vox.

- ^ Allyn B, Sprunt B (March 17, 2020). "Poll: As Coronavirus Spreads, Fewer Americans See Pandemic As A Real Threat". NPR. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- ^ Murray M (March 15, 2020). "Sixty percent believe worst is yet to come for the U.S. in coronavirus pandemic; Public attitudes about the coronavirus response are split along partisan lines in a new NBC News/Wall Street Journal poll". NBC News.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Weissmann J (March 17, 2020). "Democrats Are Being Much, Much More Careful About the Coronavirus Than Republicans". Slate.

- ^ Agiesta J (May 12, 2020). "CNN Poll: Negative ratings for government handling of coronavirus persist". CNN. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- ^ Wike R, Fetterolf J, Mordecai M (September 15, 2020). "U.S. Image Plummets Internationally as Most Say Country Has Handled Coronavirus Badly". Pew Research Center. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- ^ "Determination of the February 2020 Peak in US Economic Activity". National Bureau of Economic Research. June 8, 2020.

- ^ Long H (April 29, 2020). "U.S. economy shrank 4.8 percent in first quarter, the biggest decline since the Great Recession". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ Long H (May 8, 2020). "U.S. unemployment rate soars to 14.7 percent, the worst since the Depression era". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- ^ Abelson R (March 28, 2020). "Coronavirus May Add Billions to the Nation's Health Care Bill". The New York Times. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ Goolsbee A (2021). "Fear, Lockdown, and Diversion: Comparing Drivers of Pandemic Economic Decline 2020". Journal of Public Economics. Becker Friedman Institute for Research in Economics. 193: 104311. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104311. PMC 7687454. PMID 33262548. Retrieved June 23, 2020.

- ^ Tapee A (July 31, 2020). "US economy posts its worst drop on record". CNN. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ^ Faelli F, Rovit S, Apps C, Johns L (September 23, 2020). "Shaping the Consumer of the Future". Bain & Company. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ Rummler O (May 14, 2020). "OpenTable forecasts 25% of U.S. restaurants to shutter permanently". Axios Media. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- ^ "43 million Americans at risk of eviction as relief programs and moratorium expire: "It's a nightmare"". CBS News. July 31, 2020.

- ^ "32% of Americans had outstanding housing payments at the beginning of August". CNBC. August 6, 2020.

- ^ "'A Homeless Pandemic' Looms As 30 Million Are At Risk Of Eviction". NPR. August 10, 2020.

- ^ Ivanova I (November 27, 2020). "Nearly 19 million Americans could lose their homes when eviction limits expire Dec. 31". CBS News. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- ^ "As Stimulus Talks Stalemate, New Report Finds 40 Million Americans Could Be At Risk Of Eviction". Forbes. August 7, 2020.

- ^ "Millions of Americans at risk of eviction after moratorium expired". Fox Business. August 12, 2020.

- ^ "Yelp data shows 60% of business closures due to the coronavirus pandemic are now permanent". CNBC. September 16, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (January 1, 1939). "All Employees: Total Nonfarm Payrolls". FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Retrieved June 4, 2019.

- ^ U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (January 1, 1948). "Civilian Unemployment Rate". FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Retrieved June 4, 2019.

- ^ U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (January 1, 1948). "Unemployment level". FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- ^ U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (January 1, 1948). "Employment-Population Ration 25-54 Yrs". FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- ^ U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (January 1, 1947). "Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: All Items". FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Retrieved June 4, 2019.

- ^ "S&P 500". fred.stlouisfed.org. June 3, 2019. Retrieved June 4, 2019.

- ^ "The Debt to the Penny and Who Holds It". treasury.gov. June 10, 2021. Retrieved June 10, 2021.

- ^ Fang M (March 16, 2021). "There Have Been Nearly 4,000 Incidents Of Anti-Asian Racism In The Last Year". HuffPost. Retrieved March 16, 2021.

- ^ Van Beusekom M (September 25, 2020). "Studies spotlight COVID racial health disparities, similarities". CIDRAP – Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy, University of Minnesota. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- ^ "The color of coronavirus: COVID-19 deaths by race and ethnicity in the U.S." APM Research Lab: American Public Media. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- ^ Hollie Silverman; Konstantin Toropin; Sara Sidner; Leslie Perrot. "Navajo Nation surpasses New York state for the highest Covid-19 infection rate in the US". CNN. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- ^ "Cases, Data, and Surveillance". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). February 11, 2020. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- ^ Chowkwanyun M, Reed AL (July 2020). "Racial Health Disparities and Covid-19 – Caution and Context". New England Journal of Medicine. 383 (3): 201–203. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2012910. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 32374952. S2CID 218534431.

- ^ "The COVID Racial Data Tracker". The COVID Tracking Project (The Atlantic Monthly Group). Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- ^ Wood D (September 23, 2020). "As Pandemic Deaths Add Up, Racial Disparities Persist – And In Some Cases Worsen". NPR. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- ^ "Map: Coronavirus and School Closures". Education Week. Editorial Projects in Education. March 7, 2020. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- ^ Panetta G (March 30, 2020). "Trump baselessly claimed that expanding voting access would lead to a Republican never being elected in America again". Business Insider.

- ^ Samuels B (April 7, 2020). "Trump defends his mail-in ballot after calling vote-by-mail 'corrupt'". The Hill. Archived from the original on February 26, 2021.

- ^ Parks M (April 7, 2020). "Fact Check: Is Mail Ballot Fraud As Rampant As President Trump Says It Is?". NPR.

- ^ Warshaw C, Vavreck L, Baxter-King R (October 2020). "Fatalities from COVID-19 are reducing Americans' support for Republicans at every level of federal office". Science Advances. 6 (44): eabd8564. Bibcode:2020SciA....6.8564W. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abd8564. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 7608793. PMID 33127688.

- ^ Timeline of daily COVID-19 vaccine doses administered in the US. Click on the chart tab. Then click the download tab, and then the SVG link to get the SVG file. The table tab has a table of the data by date. The sources tab says the data is from the COVID-19 Data Repository by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University. The graph on the chart tab at the source is interactive and provides more detail. For example, run your cursor over the graph to see the date and the number vaccinated that day. The actual number may be higher or lower since a rolling 7-day average is used.

- ^ COVID-19 Vaccinations in the United States. By Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Percent of people receiving at least one COVID-19 vaccine dose by state or territory for the total population. Hover or click on the states or territories for more info.

- ^ "Interior Applauds Inclusion of Insular Areas through Operation Warp Speed to Receive COVID-19 Vaccines" (Press release). United States Department of the Interior (DOI). December 12, 2020. Retrieved January 13, 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Dorman B (January 6, 2021). "Asia Minute: Palau Administers Vaccines to Keep Country Free of COVID". Hawaii Public Radio. Retrieved January 13, 2021.

- ^ CDC (March 28, 2020). "COVID Data Tracker". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Retrieved April 23, 2021.

- ^ Thomas, Katie; Weiland, Noah; LaFraniere, Sharon (December 10, 2020). "F.D.A. Advisory Panel Gives Green Light to Pfizer Vaccine" – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ Jr, Berkeley Lovelace (December 19, 2020). "FDA approves second Covid vaccine for emergency use as it clears Moderna's for U.S. distribution". CNBC.

- ^ Machemer, Theresa. "FDA Approves Johnson & Johnson Vaccine, Another Valuable Tool Against Covid-19". Smithsonian Magazine.

- ^ Anthes, Emily; Ngo, Madeleine; Sullivan, Eileen (April 19, 2021). "Adults in all U.S. states are now eligible for vaccination, hitting Biden's target. Half have had at least one dose". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 22, 2021.

- ^ Johnson, Carolyn Y. (May 10, 2021). "FDA authorizes Pfizer coronavirus vaccine for adolescents 12 to 15 years old". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 10, 2021 – via MSN.

- ^ Jr, Berkeley Lovelace (August 23, 2021). "FDA grants full approval to Pfizer-BioNTech's Covid shot, clearing path to more vaccine mandates". CNBC. Retrieved August 23, 2021.

- ^ Betsy Klein, Veronica Stracqualursi and Kate Sullivan. "Biden unveils Covid-19 plan based on 'science not politics' as he signs new initiatives". CNN. Retrieved March 12, 2021.

- ^ "COVID-19: US president Joe Biden signs 10 executive orders to curb spread of coronavirus". Sky News. Retrieved March 12, 2021.

- ^ "100 Million Shots In 100 Days: Is Biden's COVID-19 Vaccination Goal Achievable?". NPR.org. Retrieved March 12, 2021.

- ^ "Biden Eyes New Goal After US Clears 100M Shots Since Jan. 20". HuffPost. March 20, 2021.

- ^ Dan Mangan, Berkeley Lovelace Jr. (March 25, 2021). "Biden sets new Covid vaccine goal of 200 million shots within his first 100 days: 'I believe we can do it'". CNBC. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ Pettypiece, Shannon; Shabad, Rebecca (April 21, 2021). "'We did it': Biden celebrates U.S. hitting milestone of 200 million doses in his first 100 days". NBCNews.com. Retrieved April 22, 2021.

- ^ "Biden calls on private companies to issue vaccine requirements", NBC News, August 23, 2021

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Employers Want You To Get Vaccinated. This One Is Offering A $1,000 Bonus", NPR, August 17, 2021

- ^ "As delta variant spreads, some companies with vaccine mandates deploy tech to verify records", Washington Post, August 19, 2021

- ^ "Most Americans Now Support Mask And Vaccination Mandates. Which Companies Will Follow Their Lead?", Fortune, August 23, 2021

- ^ Jump up to: a b Miguel K (February 28, 2020). "Here's a look at some of history's worst pandemics that have killed millions". KGO-TV. Retrieved March 22, 2020.

- ^ Lileks J (March 18, 2020). "How the news media played down the pandemics of yore, from Spanish flu to Swine flu". Star Tribune. Retrieved March 22, 2020.

- ^ Brown J (March 3, 2020). "The Coronavirus Is No 1918 Pandemic". The Atlantic. Retrieved March 22, 2020.

- ^ "These are the countries best prepared for health emergencies". World Economic Forum. February 12, 2020.

- ^ Maizland L, Nayeem T, Kumar A (March 24, 2020). "What a Global Health Survey Found Months Before the Coronavirus Pandemic". Council on Foreign Relations.

- ^

- Eastwood, Joel; Overberg, Paul; Barry, Rob (April 4, 2020). "Why We Don't Know How Many Americans Are Infected With Coronavirus—and Might Never Know". The Wall Street Journal.

- "Lack of testing clouds virus picture on the North Coast | Coronavirus". dailyastorian.com. April 8, 2020. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- "How Many People in the United States Actually Have COVID-19?". Healthline. March 18, 2020.

- Bosman, Julie (April 11, 2020). "Official Counts Understate the U.S. Coronavirus Death Toll—The New York Times". Nytimes.com. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- "US coronavirus map: Tracking the United States outbreak". Usatoday.com. January 28, 2020. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- Roberts, Jeff J. (April 3, 2020). "Can the private sector provide better coronavirus data? Experts are skeptical". Fortune. Retrieved April 10, 2020.

Confirmed coronavirus cases in the U.S. crossed 200,000 on Thursday, but experts agree the actual number of infected people is much higher. The lack of reliable data—a persistent problem since the pandemic began—has made it impossible to determine the actual size of the outbreak, hampering the U.S. response.