Dovecote

A dovecote or dovecot /ˈdʌvkɒt/, doocot (Scots) or columbarium is a structure intended to house pigeons or doves.[1] Dovecotes may be free-standing structures in a variety of shapes, or built into the end of a house or barn. They generally contain pigeonholes for the birds to nest.[2] Pigeons and doves were an important food source historically in the Middle East and Europe and were kept for their eggs and dung.[3]

History and geography[]

The oldest dovecotes are thought to have been the fortress-like dovecotes of Upper Egypt, and the domed dovecotes of Iran. In these regions, the droppings were used by farmers for fertilizing. Pigeon droppings were also used for leather tanning and making gunpowder.[4]

In some cultures, particularly Medieval Europe, the possession of a dovecote was a symbol of status and power and was consequently regulated by law. Only nobles had this special privilege, known as droit de colombier.

Many ancient manors in France and the United Kingdom have a dovecote still standing (or in ruins) in a section of the manorial enclosure, or in nearby fields. Examples include Château de Kerjean in Brittany, France, Houchin, France, Bodysgallen Hall in Wales, and Muchalls Castle and Newark Castle in Scotland.

Columbaria in ancient Rome[]

The presence of dovecotes is not documented in France before the Roman invasion of Gaul by Caesar. The pigeon farm was then a passion in Rome: The Roman-style, generally round, columbarium had its interior covered with a white coating of marble powder. Varro, Columella, and Pliny, all wrote about pigeon farming and dovecote construction.

In the city of Rome in the time of the Republic and the Empire the internal design of the banks of pigeonholes was adapted for the purpose of disposing of cremated ashes after death: These columbaria were generally constructed underground.

France[]

The French word for dovecote is pigeonnier or colombier. In some French provinces, especially Normandy, the dovecotes were built of wood in a very stylized way. Stone was the other popular building material for these old dovecotes. These stone structures were usually built in circular, square and occasionally octagonal form. Some of the medieval French abbeys had very large stone dovecotes on their grounds.

In Brittany, the dovecote was sometimes built directly into the upper walls of the farmhouse or manor-house.[5] In rare cases, it was built into the upper gallery of the lookout tower (for example at the Toul-an-Gollet manor in Plesidy, Brittany).[6] Dovecotes of this type are called tour-fuie in French.

Even some of the larger château-forts, such as the Château de Suscinio in Morbihan, still have a complete dovecote standing on the grounds, outside the moat and walls of the castle.

Colombiers and pigeonniers in medieval France[]

In France, it was called a colombier, fuie or pigeonnier.[7]

The dovecote interior, the space granted to the pigeons, is divided into a number of boulins (pigeon holes). Each boulin is the lodging of a pair of pigeons. These boulins can be in rock, brick or cob (adobe) and installed at the time of the construction of the dovecote or be in pottery (jars lying sideways, flat tiles, etc.), in braided wicker in the form of a basket or of a nest. It is the number of boulins that indicates the capacity of the dovecote. The ones at the chateau d'Aulnay in Aulnay-sous-Bois[8] and the one at Château de Panloy in Port-d'Envaux[9] are among the largest in France.

In the Middle Ages, particularly in France, the possession of a colombier à pied (dovecote on the ground accessible by foot), constructed separately from the corps de logis of the manor-house (having boulins from the top down), was a privilege of the seigneurial lord. He was granted permission by his overlord to build a dovecote or two on his estate lands. For the other constructions, the dovecote rights (droit de colombier) varied according to the provinces.[10] They had to be in proportion to the importance of the property, placed in a floor above a henhouse, a kennel, a bread oven, even a wine cellar. Generally, the aviaries were integrated into a stable, a barn or a shed, and were permitted to use no more than 1 hectare (2+1⁄2 acres) of arable land.[citation needed]

Middle East[]

Dotted with wooden pegs and hundreds of holes, the towers provided shelter and breeding areas for the birds to nest and raise their young in a mostly harsh desert environment. In Saudi Arabia, fourteen towers were spotted in 2020 and were the oldest seen in the Middle Eastern country. They have often been spotted in Iran, Egypt, and Qatar, where they have a lengthy history dating back to the 13th century. Dovecotes are also prevalent in ancient Iran and Anatolia. Pigeons were found in human settlements in Egypt and the Middle East since the dawn of agriculture, probably attracted to seeds people planted for their crops.[11]

Isfahan's Ancient Dovecotes[]

In the 17th century, a European traveler counted up to 3000 dovecotes in the Isfahan area of Persia (Hadizadeh, 2006, 51–4). Today, over 300 historic dovecotes have been identified in Isfahan Province and a total of 65 have been registered on the National Heritage List (Rafiei, 1974, 118–24). Dovecotes were constructed to produce large quantities of high-quality organic fertilizer for Isfahan's rich market gardens. The largest dovecotes could house 14,000 birds, and were decorated in distinctive red bands so as to be easily recognizable to the pigeons.[12]

Cappadocia's Ancient Dovecotes[]

The dove cotes in Cappadocia are mostly designed like rooms which are set up by carving the rocks. The oldest samples of these cots in the region were built in the 18th Century but they are not many. Most of the cotes in the region were built in the 19th and early 20th century (øúçen, 2008).It is significantly evident that the cotes were constructed near to water sources, on a place, above the valley and their entrance, called as mouth of the cotes were mostly built in the east or south direction of valleys. By this way of construction, it was proposed to protect the cotes from cold and get sun light inside. The cotes were generally constructed by carving the rocks as a room.[12]

Greece[]

Dovecotes in Greece are known as Περιστεριώνες, Peristeriones (plural). Such structures are very popular in the Cycladic islands and in particular Tinos, which has 1300 dovecotes.[13] The systematic breeding of doves and pigeons as sources of meat and fertilizer was introduced by the Venetians[14][15] in the 15th century. Dovecotes are built in slopes protected by the prevailing north wind and oriented so that their facade is towards an open space.

Ireland[]

Stone dovecotes were built in Ireland from the Norman period onward, to supply meat to monastic kitchens and to large country houses.[16] A traditional dovecote was a multistorey building with inner walls lined with alcoves or ledges to mimic a cave.[17] They survive in many parts of Ireland, with notable examples at Ballybeg Priory,[18] Oughterard,[19] Cahir,[20] Woodstock Estate, Mosstown, Adare.[21][22] Three Irish Cistercian houses held dovecotes: St. Mary's Abbey, Glencairn, Mellifont Abbey and Kilcooley Abbey.[23]

Italy[]

Dovecotes were included in several of the villa designs of Andrea Palladio. As an integral part of the World Heritage Site "Vicenza and the Palladian Villas of the Veneto", dovecotes such as those at Villa Barbaro enjoy a high level of protection.

Netherlands and Belgium[]

Dovecotes in Belgium are mostly associated with pigeon racing. They have special features, such as trap doors that allow pigeons to fly in, but not out. The Flemish word for dovecote is "duivenkot". The Dutch word for dovecote is "duiventoren", or "duiventil" for a smaller dovecot.

Spain[]

Dovecotes in Spain are known as a Palomar or Palomares (plural). These structures are very popular in the Tierra de Campos region and also has a scale model of this type of building at a Theme Park located in the Mudéjar de Olmedo. Other good examples are located at Museums located in Castroverde de Campos, (Zamora Province), Villafáfila, (Zamora Province), Santoyo, (Palencia Province) and the famous "Palomar de la Huerta Noble" in the municipality of Isla Cristina (Huelva Province) which was built in the 18th century to house 36,000 pigeons.

Transylvania[]

The Szekely people of Transylvania incorporate a dovecote into the design of their famous gates. These intricately carved wooden structures feature a large arch with a slatted door, which is meant to admit drivers of carriages and wagons (although today the visitors are probably driving cars and trucks), and a smaller arch with a similar door for pedestrians. Across the top of the gate is a dovecote with 6-12 or more pigeonholes and a roof of wooden shingles or tiles.[24]

England and Wales[]

The Romans may have introduced dovecotes or columbaria to Britain since pigeon holes have been found in Roman ruins at Caerwent. However, it is believed that doves were not commonly kept there until after the Norman invasion.[citation needed] The earliest known examples of dove-keeping occur in Norman castles of the 12th century (for example, at Rochester Castle, Kent, where nest-holes can be seen in the keep), and documentary references also begin in the 12th century. The earliest surviving, definitely dated free-standing dovecote in England was built in 1326 at Garway in Herefordshire.[25] The Welsh name colomendy has itself become a place name (similarly in Cornwall:colomen & ty = dove house). One medieval dovecote still remains standing on the site of a hall at Potters Marston in Leicestershire, a hamlet near to the village of Stoney Stanton.

Scotland[]

Early purpose-built doocots in Scotland are often of a "beehive" shape, circular in plan and tapering up to a domed roof with a circular opening at the top. These are also found in the North of England and are sometimes referred to as "tun-bellied".[26] In the late 16th century, they were superseded by the "lectern" type, rectangular with a mono-pitched roof sloping fairly steeply in a suitable direction.[27] Phantassie Doocot is an unusual example of the beehive type topped with a mono-pitched roof, and Finavon Doocot of the lectern type is the largest doocot in Scotland, with 2,400 nesting boxes. Doocots were built well into the 18th century in increasingly decorative forms, then the need for them died out though some continued to be incorporated into farm buildings as ornamental features. However, the 20th century saw a revival of doocot construction by pigeon fanciers, and dramatic towers clad in black or green painted corrugated iron can still be found on wasteland near housing estates in Glasgow and Edinburgh.[28][29]

A castle doocot at Corstorphine, Edinburgh (16thC)

Bee-hive shaped doocot, Linlithgow, Scotland

At Newark Castle, Port Glasgow, a corner tower of the outer defensive wall was converted to a doocot in 1597 when the wall was demolished.

Doocot at Auchmacoy, , Aberdeenshire, built 1638.

Looking up inside the doocot at Newark Castle

Lectern-style doocot at the site of the old Eglinton Mains farm in Ayrshire, Scotland Doocot at the Eglinton castle stables courtyard Nesting boxes in the Eglinton doocot Ruined doocot at Newbigging near Aberdour, Scotland, revealing the nesting boxes

Bogward Doocot, St Andrews, restored by the St Andrews Preservation Trust

Mills at Milton of Campsie with a tall doocot in the background.[30]

16th-century doocot at Phantassie, East Lothian

Lady Kitty's Doocot at Haddington, Scotland, incorporated into a garden wall

Doocot converted from the stair tower of a demolished house at Sheriffhall near Dalkeith, Scotland

Two house doocots in the West Bow, Edinburgh, Scotland

Doocot c. 1730 in the grounds of a private house, Edinburgh, Scotland

Urban doocot in Glasgow, Scotland

Urban doocot in Glasgow, Scotland

North America[]

In the U.S., an alternative English name for dovecotes is pigeonaire (from French). This word is more common than "dovecote" in Louisiana and other areas with a heavy Francophonic heritage.

Québec City, Canada, has a pigeonnier that stands in a square in Old Québec; the Pigeonnier is also the name of the square itself and is where street artists present their shows.

A notable frame dovecote is located at Bowman's Folly, added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1974.[31][32]

Architecture[]

Functional[]

This section does not cite any sources. (September 2016) |

Their location is chosen away from large trees that can house raptors and shielded from prevailing winds and their construction obeys a few safety rules: tight access doors and smooth walls with a protruding band of stones (or other smooth surface) to prohibit the entry of climbing predators (martens, weasels...). The exterior façade was, if necessary, only evenly coated by a horizontal band, in order to prevent their ascent.

The dovecote materials can be very varied and shape and dimension extremely diverse:

- square dovecote with quadruple vaulting

- built before the fifteenth-century (Roquetaillade Castle, Bordeaux) or Saint-Trojan near Cognac

- cylindrical tower

- fourteenth century to the sixteenth century, and common until the present in parts of Spain, it is covered with curved tiles, flat tiles, stone lauzes roofing and occasionally with a dome of bricks. A window or skylight is the only opening.

- dovecote on stone or wooden pillars

- cylindrical, hexagonal or square;

- hexagonal dovecote

- like the dovecotes of the Royal Mail at Sauzé-Vaussais;

- square dovecote with flat roof tiles

- seventeenth century and a slate roof in the eighteenth century;

- lean-to structure

- propped against the sides of buildings.

Inside, a dovecote could be virtually empty (boulins being located in the walls from bottom to top), the interior reduced to only housing a rotating ladder, or "potence", that facilitated maintenance and the collection of eggs and squabs.

Decorative[]

Gable and rooftop dovecotes are associated with storybook houses with whimsical design elements.[33]

A dovecote is a small, decorative shelter for pigeons, often built on top of a house. It looks like a receptacle for secret messages from a fairy-tale world, and this whimsy makes up for the fact that no one actually wants pigeons roosting on their house. Dovecotes are especially common in certain parts of the Los Angeles suburbs, on ‘storybook ranch’ homes — houses recast on the exterior to resemble a cottage that one of the Seven Dwarves might live in.[34]

Gallery[]

Peper Harow Dovecote

Manorbier Dovecote

A dovecote in the Tarn-et-Garonne department of France, near Lauzerte

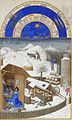

The month of February in the Limburg Brothers' Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, a painting dated 1416, showing a dovecote

The Dovecote, Listed 16th-century dovecote in Long Wittenham.[35]

Dovecote at the Abbaye Saint-Vincent in Le Mans, France

Dovecote at High House Purfleet, Essex

A colombier (dovecote) in Jersey, Channel Islands

The Pigeon Tower at Rivington on the West Pennine Moors, England

Small dovecote at the Lost Gardens of Heligan

Hudson Valley dovecote in Saugerties, New York

Palomar (dovecote) in Tierra de Campos, Spain

Nesting holes on inside walls of an old dovecote, Palazuelo de Vedija (Tierra de Campos), Spain

Hexagonal pigeonnier with a pointed roof at Uncle Sam Plantation near Convent, Louisiana

A (derelict) dovecot in Zemst, Belgium

Modern dovecote designed by Oscar Niemeyer and located on the Praça dos Três Poderes (Three Powers Plaza) in Brasília, Brazil

Pigeon house in Neduntheevu, used by colonial powers (Portuguese, Dutch or British during their rule in Sri Lanka)

Shirley Plantation dovecote interior

See also[]

- Chabutro

- Columbarium – repository of cinerary urns, the word originally denoted a dovecote

- Culverhouse – old English for dovecote

- Cunninghamhead – An example of a small doocot

- Museum of Scottish Country Life – An example of a doocot on a cart shed

- Pigeon keeping

- Pigeon racing – More on the sport

- Squab (food) – The meat from birds kept in a dovecote

References[]

- ^ Fenech, Natalino (22 September 2007). Historic dovecote in danger of collapse. Times of Malta. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ^ "Doocot Interior 1 photo - Duncan Smith photos". Pbase.com. Retrieved 2012-06-04.

- ^ "Pigeoncote.com". Pigeoncote.com. Retrieved 2012-06-04.

- ^ Tepper; Rosen; Haber; Bar-Oz (2017). "Signs of soil fertigation in the desert: A pigeon tower structure near Byzantine Shivta, Israel". Journal of Arid Environments. 145: 81–89. doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2017.05.011.

- ^ "Les façades à boulins". Pharouest.ac-rennes.fr. Archived from the original on 2012-03-04. Retrieved 2012-06-04.

- ^ "Les tours-fuies: manoir de Toul-an-Gollet". Pharouest.ac-rennes.fr. Archived from the original on 2012-03-04. Retrieved 2012-06-04.

- ^ Lolme, J. L. de. French and English dictionary. Cassell & Company.

- ^ "château d'Aulnay - Patrimoine - Atlas de l'architecture et du patrimoine". patrimoine.seinesaintdenis.fr.

- ^ "Château de Panloy (17) : un toit neuf pour le pigeonnier de 400 ans". SudOuest.fr (in French).

- ^ Musset, Jacqueline (1984). "Le droit de colombier en Normandie sous l'Ancien Régime". Annales de Normandie. pp. 51–67. doi:10.3406/annor.1984.6380.

- ^ "Historical Adobe Pigeon Towers Located Near Riyadh Captured in Photographs by Rich Hawkins". Colossal. 2020-02-13. Retrieved 2020-09-08.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Download Limit Exceeded". citeseerx.ist.psu.edu. Retrieved 2020-09-08.

- ^ Guides, Fodor's Travel. Fodor's Essential Greek Islands: with Great Cruises & the Best of Athens. Fodor's Travel. ISBN 978-1-64097-007-6.

- ^ Siger, Jeffrey. Target: Tinos. Sourcebooks, Inc. ISBN 978-1-61595-400-1.

- ^ Heikell, Rod. Greek Waters Pilot. Imray Laurie Norie & Wilson. ISBN 978-0-85288-146-0.

- ^ Warner, Dick (January 22, 2007). "Pigeon a feather in cap of world history". Irish Examiner.

- ^ Coitir, Niall Mac (September 28, 2015). Ireland's Birds. Gill & Macmillan Ltd. ISBN 9781848894983 – via Google Books.

- ^ Jackman, Neil. "Heritage Ireland: Discovering the ancient Slí Mhór among the bluebells". TheJournal.ie.

- ^ "Oughterard Dovecote | Dovecote in Oughterard | Connemara Dovecote".

- ^ "What's going on in Cahir? - You'll be pleasantly surprised to see!". www.tipperarylive.ie.

- ^ "Trinitarian Abbey, BLACKABBEY, Adare, County Limerick". Buildings of Ireland.

- ^ "Dovecote". The Irish Aesthete.

- ^ Lynch, Dr Breda (November 5, 2010). A Monastic Landscape: The Cistercians in Medieval Ireland. Xlibris Corporation. ISBN 9781477165966 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Photo". Archived from the original on 2012-02-22.

- ^ Spandl, Klara (1998) British Archaeology, London: Exploring the round houses of doves; Issue no 35, June 1998 ISSN 1357-4442

- ^ Historic England. "Dovecote S of Glebe Farm, Embleton (1006572)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2020-01-20.

- ^ "Doocots in Scotland". Ihbc.org.uk. Retrieved 2012-06-04.

- ^ "Foo's yer doos – aye pickin?". Leopardmag.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2012-09-12. Retrieved 2012-06-04.

- ^ Iain Johnstone & Sharon Halliday, HIDDEN GLASGOW 2001, www.hiddenglasgow.com. "doocots (dookits)". Hiddenglasgow. Retrieved 2012-06-04.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Stoddart, John (1800), Remarks on local Scenery and Manners in Scotland. London: William Miller;facing p. 206

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ "Bowman's Folly" (PDF). Department of Historic Resources / Virginia Historic Landmarks Commission. National Register of Historic Places inventory nomination form. Commonwealth of Virginia. n.d. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-09-26. Retrieved 2013-05-13. and Image accompanying Bowman's Folly nomination (photograph). Archived from the original on 2012-09-26.

- ^ "Revival period" (PDF). LA City Preservation.

- ^ "Letter of Recommendation". NY Times magazine. A Field Guide to American Houses. 2016-01-10.

- ^ Robert Stephenson (1986), Conversion of Listed 16th-century Dovecote.

Further reading[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dovecotes. |

- Cooke, Arthur (1920) A Book of Dovecotes London: T. N. Foulis

- Emery, Gordon Curious Clwyd ISBN 1-872265-99-5 (includes a list of dovecotes in Flintshire, Denbighshire and Wrexham with many photo examples)

- Emery, Gordon (1996) Curious Clwyd; 2 ISBN 1-872265-97-9

- The Pigeon Cote; compiled by John Verburg / Includes an annotated edition of A Book of Dovecotes and much more information on British dovecotes

- Castels of the Fields pigeon towers near Isfahan

- Commentary and video on the Eglinton Dovecote

- Commentary and examples of Scottish Doocots

- Dovecotes

- Domestic pigeons

- Buildings and structures used to confine animals