Dromornis stirtoni

It has been suggested that this article be merged into Dromornis. (Discuss) Proposed since May 2021. |

| Dromornis stirtoni | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | †Gastornithiformes |

| Family: | †Dromornithidae |

| Genus: | †Dromornis |

| Species: | †D. stirtoni

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Dromornis stirtoni | |

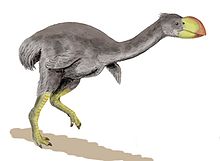

Dromornis stirtoni was a species of the genus Dromornis, a part of the Dromornithidae family, and was colloquially known as Stirton's thunderbird. It was a large feathered bird that grew up to heights of 2.5m and weights in excess of 450 kg and is widely thought to have been the largest avian species to have ever existed. Patricia Vickers-Rich first discovered the remains of the bird in 1979 in the Alcoota Fossil Beds in the Northern Territory of Australia. The bird was characterised by a deep lower jaw and quadrate bone, large, muscular hind legs with hoof-like toes, and small wings that deemed it flightless. The bird is largely thought to have been mostly herbivorous, although they may have occasionally scavenged or eaten small prey. Dromornis stirtoni is thought to have lived in a semi-arid climate, characterised by seasonal rainfall and open woodlands.

Taxonomy[]

The description of this species, along with several other new dromornithids was published in 1979 by Patricia Vickers-Rich. This included a major revision of the family, described a century earlier in Richard Owen's 1874 publication of a new species and genus. Large amounts of fragmentary material is found at the Alcoota fossil site in Central Australia, the type location, is the only certain occurrence of the bird. Rich proposed the specific epithet for fellow palaeontologist Ruben A. Stirton,[2][1] an American who undertook extensive research on Australian taxa.

Informal names for the species include Stirton's thunderbird and Stirton's mihirung.[3][4]

Description[]

Dromornis stirtoni was a large feathered bird which grew up to 2.5m in height.[3] This height is thought to have exceeded the tallest species of the genus Dinornis, which were the giant moas of New Zealand. This species is from the Dromornithidae family, which is a family of large flightless birds endemic to Australia. The weight of the animal is also thought to have been exceedingly large. Peter F. Murray and Patricia Vickers-Rich, in their work ‘Magnificent Mihirungs (2004)’, utilised three varying scientific methods to derive the approximate weight and size of the D. stirtoni.[4] This thorough analysis of the bones of D. stirtoni revealed that there was considerable sexual dimorphism, and that a fully grown male could weigh between 528 and 584 kg (1,164 and 1,287 lb), whilst a female would likely weigh between 441 and 451 kg (972 and 994 lb).[5] The disparity in robustness was interpreted by the researchers as evidence of the biology of the species, behaviours such as incubation by the female, pair bonding, parental care and aggression while nesting, and courtship or display habits exhibited by extant waterfowl, the anseriforms.[6] In comparison to other known ratite elephant birds of the Aepyornithidae family, this made D. stirtoni the heaviest of all known discoveries. D. stirtoni was compared to Aepyornis maximus by the authors, the largest of that family.

D. stirtoni was characterised by a deep lower jaw and a quadrate bone (which connects the upper and lower jaws) that was distinctly shaped. This narrow, deep bill, made up approximately two thirds of the skull. The front of this powerful jaw was used to cut, whilst the back of the jaw was used for crushing.[7] Comparison of two partial crania with the near complete cranium of Dromornis planei (Bullockornis) shows the head of this species to be about 25% larger . Reconstruction of overlapping remains of the rostrum have revealed its form and size, the lower mandible would have been around 0.5 metres. The size and proportions of the head and its bill are comparable to that of mammals such as camels or horses

The large bird had ‘stubby’, reduced wings, which ultimately deemed it flightless. However, whilst the bird was flightless, a strong development between the bony crests and tuberosities, where the wings were attached, allowed them to flap their wings.[3] The bird was also characterised by its large hind legs, which after the completion of biomechanical studies are confirmed to have been muscular, rather than slender, due to the size of the muscle attachments along the leg.[1] Due to the muscularity of these legs, D. stirtoni is thought to have possibly been capable of running at great speeds, whereas birds such as the emu depend on the slenderness of their legs to reach higher speeds.[7] D. stirtoni was also characterised by its large, hoof-like toes, which had convex nails, rather than claws.[3] Further typical of flightless birds, it did not have a breastbone.

Two forms of unearthed specimens are considered to be due to strong sexual dimorphism, concluded in a 2016 morphometric analysis using landmark based and actual measurements which also supported earlier conclusions regarding the species enormous size.[8] This histological technique has been applied to other large and extinct avian species, including investigation into the paleobiology of the elephant birds Aepyornithidae.[7]

Habitat[]

At present the only recorded fossil discoveries of Dromornis stirtoni have been from the Alcoota Fossil Beds.[3] This region is renowned for the discovery of well-preserved vertebrate fossils from the Miocene epoch (24–5 million years ago). At this location, the fossil deposits are found in the Waite Formation, which consists of sandstones, limestones and siltstones.[7] The various fossils that have been found within this region suggest that they were laid in episodical channels, characterised by a large series of interconnected lakes, within a large basin.[9]

The vegetation type of the region in that period was open woodland favouring its semi-arid climate, within which seasonal rainfall occurs.[3] D. stirtoni is found amongst the depositions of the Alcoota and Ongeva Local Faunas, dated to the Late Miocene and early Pliocene. Fragmentary remains are common at these sites, although little is assignable to an individual of the species. Some depositions contain fragments of around four individuals in disarray over an area of one square metre. Other dromornithid species have been found alongside this species, Ilbandornis woodburnei and the tentatively placed Ilbandornis lawsoni, resembling the large but more gracile modern birds such as ostriches and emus.[4]

The concentration of dromornithid species, and more generally, other fossils within this area is indicative of the phenomenon known as ‘waterhole-tethering’, whereby animals would accumulate within the immediate area of water sources, many of which would then die.[4] Whilst this is the only location that D. stirtoni have been discovered, discovery of other species within the Dromornithidae family suggests that they may have been distributed across Australia.[4] Various Dromornithidae fossils have been found in Riversleigh (Queensland) and Bullocks Creek (Northern Territory), as well as tracks in Pioneer (Tasmania).[10]

D. stirtoni probably existed in an assemblage of fauna that included other dromornithids and browsing marsupials as the apex herbivores. The Alcoota Local Fauna were deposited at the only known upper Miocene fossil beds of Central Australia. The early conceptions of a fearsome bird receives some support from the proposed behaviour of the larger males aggressively defending a preferred range against competitors, other males or herbivores, and predators.[5][6]

Feeding and diet[]

It is widely accepted that Dromornis stirtoni was a herbivorous bird, predominantly eating seed pods and tough-skinned fruits.[3] This has been deduced from various key features of the bird. One of these features is that the end of the bird's bill, does not have a hook, and that the beak is instead wide, narrow and blunt, typical of a herbivore.[7] The bird also had hoof-like feet, rather than 'talons', which are typically associated with carnivores or omnivores. Moreover, placement of the eyes on the side of the birds head prohibits it from seeing directly in front, which would limit its ability to hunt.[6][11] Lastly, analysis of the amino acids within the egg shells of D. stirtoni suggest that the species was herbivorous. Despite this however, there are various indicators that suggest the bird may have been carnivorous or omnivorous (Murray, 2004). The size and muscularity of the birds skull and beak would also suggest that they may not have been herbivores, as no source of vegetable food in their environment would have required such a powerful beak (Vickers-Rich, 1979). In recognition of the varying opinions, it is widely accepted that whilst the large bird may have occasionally scavenged or eaten smaller prey, they were mostly herbivorous. [12]

Extinction[]

It is proposed that various factors may have contributed to the extinction of Dromornis stirtoni. Palaeontologists Murray and Vickers-Rich suggested that the diet may have overlapped considerably with the diets of other large birds and animals, and that the subsequent converging trophic morphology could have contributed to the large birds extinction as it was 'out-competed' of its food source.[4]

Alternate arguments have proposed that the large birds' breeding patterns may have contributed. This suggested that D. stirtoni lived for a relatively long period of time in a group of older birds, however, for the few young that were produced, time to maturity was considerable. Subsequently, breeding adults were replaced slowly, which left the species highly vulnerable if breeding adults were lost.[6]

It is thought that these factors may have worked in conjunction with the introduction of humans, and the predation and environmental modification that was associated. Modern researchers, think that with the arrival of early Aboriginal Australians (around 70,000~65,000 years ago), hunting and the use of fire to manage their environment may have contributed to the extinction of the megafauna.[13] Increased aridity during peak glaciation (about 18,000 years ago) may have also contributed, but most of the megafauna were already extinct by this time. Steve Wroe made note that there is arguably an insufficient level of data to definitively determine the time of extinction of many of Australia's megafauna, and more specifically D. stirtoni. They suggest that many of the extinctions had been staggered over the course of the late Middle Pleistocene and early Late Pleistocene, prior to human arrival, due to climatic stress.[14] Whilst direct evidence of human predation of D. stirtoni is limited, various experts propose that the large bird may well have been hunted, recognising that more than 85% of Australian mega fauna became extinct during the same period that humans were introduced.[15] The use of 'fire-stick burning' as an ecosystem management technique is thought to have adversely impacted the semi-arid climates within which D. stirtoni lived, as the ecosystem lacked the required resilience, and as such, food supplies were impacted.[15]

New evidence based on accurate optically stimulated luminescence and uranium-thorium dating of megafaunal remains suggests that humans were the ultimate cause of the extinction for some of the megafauna in Australia.[16][17] The dates derived show that all forms of megafauna on the Australian mainland became extinct in the same rapid timeframe—approximately 46,000 years ago — the period when the earliest humans first arrived in Australia (around 70,000~65,000 years ago long chronology and 50,000 years ago short chronology).[13] However, these results were subsequently disputed, with another study showing that 50 of 88 megafaunal species have no dates postdating the penultimate glacial maxiumum around 130,000 years ago, and there was only firm evidence for overlap of 8-14 megafaunal species with people.[14] Analysis of oxygen and carbon isotopes from teeth of megafauna indicate the regional climates at the time of extinction were similar to arid regional climates of today and that the megafauna were well adapted to arid climates.[16] The dates derived have been interpreted as suggesting that the main mechanism for extinction was human burning of a landscape that was then much less fire-adapted; oxygen and carbon isotopes of teeth indicate sudden, drastic, non-climate-related changes in vegetation and in the diet of surviving marsupial species.

Chemical analysis of fragments of eggshells of Genyornis newtoni, a flightless bird similar to D. stirtoni, revealed scorch marks consistent with cooking in human-made fires, presumably the first direct evidence of human contribution to the extinction of a species of the Australian megafauna.[18] This was later contested by another study that noted the too small dimensions (126 x 97 mm, roughly like the emu eggs, while the moa eggs were about 240 mm) for the Genyornis supposed eggs, and rather, attributed them to another extinct, but much smaller bird, the megapode Progura.[19] The real time that saw Genyornis vanish is still an open question, but this was believed as one of the best documented megafauna extinctions in Australia.

References[]

- ^ a b c Rich, P.V. 1979. The Dromornithidae, a family of large,extinct ground birds endemic to Australia: Systematic and phylogenetic considerations. Canberra Bureau of Mineral Resources, Geology and Geophysics Bulletin 184, 1–196.

- ^ " Dromornis Der schwerste Vogel aller Zeiten". GRIN (in German). Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Musser, Anne. "Stirton's Thunder Bird". The Australian Museum. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Murray, Peter; Vickers-Rich, Patricia (2004). Magnificent mihirungs : the colossal flightless birds of the Australian dreamtime. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 50–51. ISBN 978-0-253-34282-9.

- ^ a b Chinsamy, A., Handley, W. D., Yates. A. M., Worthy, T. H. (2016). Sexual dimorphism in the late Miocene mihirung Dromornis stirtoni (Aves: Dromornithidae) from the Alcoota Local Fauna of central Australia. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 36:5, DOI: 10.1080/02724634.2016.1180298

- ^ a b c d Handley, W. D.; A. Chinsamy; A. M. Yates & T. H. Worthy (2016), "Sexual dimorphism in the late Miocene mihirung Dromornis stirtoni (Aves: Dromornithidae) from the Alcoota Local Fauna of central Australia", Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, doi:10.6084/M9.FIGSHARE.3422146.V1

- ^ a b c d e Monroe, M. (2009). Dromornithidae. Retrieved from Australia Through Time:https://austhrutime.com/dromornithidae.htm

- ^ Puiu, T. (2021). Giant Australian flightless bird was ‘extreme evolutionary experiment’. Retrieved from ZME Science: https://www.zmescience.com/ecology/animals-ecology/giant-australian-flightless-bird-24032021/

- ^ Museum, A. (2018). Fossils in Alcoota, NT . Retrieved from Australian Museum: https://australian.museum/learn/australia-over-time/fossils/sites/alcoota/

- ^ Nguyen, J. (2019). Dromornis planei (Bullockornis planei) . Retrieved from Australian Museum: https://australian.museum/learn/australia-over-time/extinct-animals/dromornis-planei-bullockornis-planei/

- ^ Ellis, Richard (2004). No turning back : the life and death of animal species (1st ed.). New York, NY: HarperCollins. p. 102. ISBN 0-06-055803-2.

- ^ Angst, Delphine; Buffetaut, Eric (2017-01-01). "4 Dromornithidae". Paleobiology of Giant Flightless Birds. Elsevier. doi:10.1016/b978-1-78548-136-9.50004-0. ISBN 978-1-78548-136-9.

- ^ a b Miller, G. H. (2005). "Ecosystem Collapse in Pleistocene Australia and a Human Role in Megafaunal Extinction". Science. 309 (#5732): 287–290. Bibcode:2005Sci...309..287M. doi:10.1126/science.1111288. PMID 16002615. S2CID 22761857.

- ^ a b Wroe, S.; Field, J. H.; Archer, M.; Grayson, D. K.; Price, G. J.; Louys, J.; Faith, J. T.; Webb, G. E.; Davidson, I.; Mooney, S. D. (2013-05-28). "Climate change frames debate over the extinction of megafauna in Sahul (Pleistocene Australia-New Guinea)". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (#22): 8777–8781. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.8777W. doi:10.1073/pnas.1302698110. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3670326. PMID 23650401.

- ^ a b Miller, Gifford H.; Magee, John W.; Johnson, Beverly J.; Fogel, Marilyn L.; Spooner, Nigel A.; McCulloch, Malcolm T.; Ayliffe, Linda K. (1999-01-08). "Pleistocene Extinction of Genyornis newtoni: Human Impact on Australian Megafauna". Science. 283 (5399): 205–208. doi:10.1126/science.283.5399.205. PMID 9880249.

- ^ a b Prideaux, G. J.; Long, J. A.; Ayliffe, L. K.; Hellstrom, J. C.; Pillans, B.; Boles, W. E.; Hutchinson, M. N.; Roberts, R. G.; Cupper, M. L.; Arnold, L. J.; Devine, P. D.; Warburton, N. M. (2007-01-25). "An arid-adapted middle Pleistocene vertebrate fauna from south-central Australia". Nature. 445 (#7126): 422–425. Bibcode:2007Natur.445..422P. doi:10.1038/nature05471. PMID 17251978. S2CID 4429899.

- ^ Saltré, Frédérik; Rodríguez-Rey, Marta; Brook, Barry W.; Johnson, Christopher N; Turney, Chris S. M.; Alroy, John; Cooper, Alan; Beeton, Nicholas; Bird, Michael I.; Fordham, Damien A.; Gillespie, Richard; Herrando-Pérez, Salvador; Jacobs, Zenobia; Miller, Gifford H.; Nogués-Bravo, David; Prideaux, Gavin J.; Roberts, Richard G.; Bradshaw, Corey J. A. (2016). "Climate change not to blame for late Quaternary megafauna extinctions in Australia". Nature Communications. 7: 10511. Bibcode:2016NatCo...710511S. doi:10.1038/ncomms10511. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 4740174. PMID 26821754.

- ^ Miller, Gifford; Magee, John; Smith, Mike; Spooner, Nigel; Baynes, Alexander; Lehman, Scott; Fogel, Marilyn; Johnston, Harvey; Williams, Doug; Clark, Peter; Florian, Christopher (2016-01-29). "Human predation contributed to the extinction of the Australian megafaunal bird Genyornis newtoni ∼47 ka". Nature Communications. 7 (1): 10496. doi:10.1038/ncomms10496. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 4740177. PMID 26823193.

- ^ Grellet-Tinner, Gerald; Spooner, Nigel A.; Worthy, Trevor H. (February 2016). "Is the "Genyornis" egg of a mihirung or another extinct bird from the Australian dreamtime?". Quaternary Science Reviews. 133: 147–164. Bibcode:2016QSRv..133..147G. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2015.12.011. hdl:2328/35952.

External links[]

- Dromornis

- Miocene birds

- Prehistoric animals of Australia