Edict of Expulsion

| This is a part of the series on |

| History of the Jews in England |

|---|

| Medieval |

| Blood libel in England |

| Modern |

| Related |

The Edict of Expulsion was a royal decree issued by King Edward I of England on 18 July 1290 expelling all Jews from the Kingdom of England. Edward advised the sheriffs of all counties he wanted all Jews expelled by no later than All Saints' Day (1 November) that year. The expulsion edict remained in force for the rest of the Middle Ages. The edict was not an isolated incident, but the culmination of over 200 years of increasing antisemitism. The edict was overturned during the Protectorate more than 350 years later, when Oliver Cromwell permitted Jews to return to England in 1657.[1]

Background[]

The first Jewish communities of significant size came to England with William the Conqueror in 1066, when William issued an invitation to the Jews of Rouen to move to England, likely because he wanted feudal dues to be paid to the royal treasury in coin rather than in kind, and for this purpose it was necessary to have a body of men scattered through the country who would supply quantities of coin.[2][3] After the Norman Conquest, William instituted a feudal system in the country, whereby all estates formally belonged to the Crown; the king then appointed lords over these vast estates, but they were subject to duties and obligations (financial and military) to the king. Under the lords were other subjects such as serfs, who were bound and obliged to their lords, and to their lords' obligations. Merchants had a special status in the system, as did Jews. Jews were declared to be direct subjects of the king,[4] unlike the rest of the population. This was an ambivalent legal position for the Jewish population, in that they were not tied to any particular lord but were subject to the whims of the king, and it could be either advantageous or disadvantageous. Every successive king formally reviewed a royal charter, granting Jews the right to remain in England. Jews did not enjoy any of the guarantees of the Magna Carta[5] of 1215.

Economically, Jews played a key role in the country. The Church then strictly forbade the lending of money for profit, creating a vacuum in the economy of Europe that Jews filled because of extreme discrimination in every other economic area.[6] Canon law was not considered applicable to Jews, and Judaism does not forbid loans with interest between Jews and non-Jews.[7] Taking advantage of their unique status as his direct subjects, the King could appropriate Jewish assets in the form of taxation. He levied heavy taxes on Jews at will, without having to summon Parliament.[8]

The reputation of Jews as extortionate money-lenders arose, which made them extremely unpopular with both the Church and the general public. While an anti-Jewish attitude was widespread in Europe, medieval England was particularly anti-Jewish.[5] An image of the Jew as a diabolical figure who hated Christ started to become widespread, and myths such as the tale of the Wandering Jew and allegations of ritual murders originated and spread throughout England as well as in Scotland and Wales.[9]

In frequent cases of blood libel, Jews were said to hunt for children to murder before Passover so that they could use their blood to make the unleavened matzah.[10] Anti-Jewish attitudes sparked numerous riots in which many Jews were murdered, most notably in 1190, when over 100 Jews were massacred in York.[10]

Expulsion[]

The situation only got worse for Jews as the 13th century progressed. In 1218, Henry III of England proclaimed the Edict of the Badge requiring Jews to wear a marking badge.[11] Taxation grew increasingly intense. Between 1219 and 1272, 49 levies were imposed on Jews for a total of 200,000 marks, a vast sum of money.[8] In 1222, Stephen Langton, Archbishop of Canterbury, convened the Synod of Oxford which passed a set of laws that forbade Jews to build new synagogues, own slaves, or mix with Christians in England.[12] Henry III imposed greater segregation and reinforced the wearing of badges in the 1253 Statute of Jewry. He endorsed the myth of Jewish child murders. Meanwhile, his court and major Barons bought Jewish debts with the intention of securing lands of lesser nobles through defaults. The Second Barons' War in the 1260s brought a series of pogroms aimed at destroying the evidence of these debts and Jewish communities in major towns, including London (where 500 Jews died), Worcester, Canterbury, and many other towns.[3]

The first major step towards expulsion took place in 1275, with the Statute of the Jewry. The statute outlawed all lending at interest and gave Jews fifteen years to readjust.[13] In 1282, John Peckham, the Archbishop of Canterbury, closed all synagogues in his diocese.[3]

In the duchy of Gascony in 1287, King Edward ordered the local Jews expelled.[14] All their property was seized by the crown and all outstanding debts payable to Jews were transferred to the King's name.[15] In late 1286, Pope Honorius IV addressed a special rescript to the Archbishops of York and Canterbury claiming that the Jews had an evil effect on religious life in England through free interaction with Christians and called for action to be taken to prevent it. The Church responded with the Synod of Exeter in 1287, restating the Church laws against commensality between Jews and Christians and prohibiting Jews from holding public office, have Christian servants, or appear in public during Easter. Jewish physicians were also forbidden to practice and the ordinances of the Synod of Oxford of 1222 which prohibited the construction of new synagogues and the entry of Jews into Churches were restated.[3]

By the time he returned to England in 1289, King Edward was deeply in debt.[16] The next summer he summoned his knights to impose a steep tax. To make the tax more palatable, Edward, in exchange, essentially offered to expel all Jews.[17] The heavy tax was passed, and three days later, on 18 July,[18] the Edict of Expulsion was issued.[17]

One official reason for the expulsion was that Jews had declined to follow the Statute of Jewry and continued to practice usury. This is quite likely, as it would have been extremely hard for many Jews to take up the respectable occupations demanded by the Statute. The edict of expulsion was widely popular and met with little resistance, and the expulsion was quickly carried out.[citation needed]

Writs were issued to the sheriffs of every county that all Jews should leave England by All Saint's Day. The Jews were allowed to take their portable possessions with them but the vast majority had their houses forfeited to the king. A few favored persons were allowed to sell their homes before they left.[3]

The Jewish population in England at the time was relatively small, perhaps 2,000 people, although estimates vary.[19] Holinshed's Chronicles recounted an incident of a ship chartered by wealthy Jews toward the mouth of the Thames, near Queenborough, en route to France. While the tide was low, the captain convinced the Jews to walk with him on a sandbank. He then returned to the ship before the tide came back in, leaving the Jews to drown, and he returned to London with their possessions. Though several of the mariners were hanged for their involvement, Holinshed also recounted that the captain was thanked and rewarded by the king.[20][15]

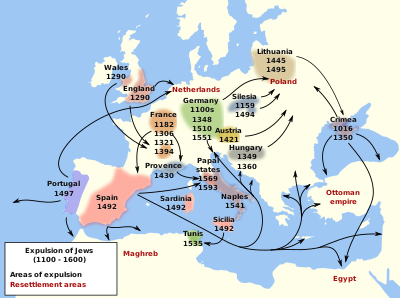

Many Jews emigrated, to Scotland, France and the Netherlands, and as far as Poland, which guaranteed their legal rights (see Statute of Kalisz).

Intermediate period[]

Between the expulsion of Jews in 1290 and their formal return in 1655, there are records of Jews in the Domus Conversorum up to 1551 and even later. An attempt was made to obtain a revocation of the edict of expulsion as early as 1310, but in vain. Notwithstanding, a certain number of Jews appeared to have returned; four complaints were made to the king in 1376 that some of those trading as Lombards were actually Jews.[21]

Occasionally permits were given to individuals to visit England, as in the case of Dr Elias Sabot (an eminent physician from Bologna summoned to attend Henry IV) in 1410, but it was not until the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492 and Portugal in 1497 that any considerable number of Sephardic Jews found refuge in England. In 1542 many were arrested on the suspicion of being Jews, and throughout the sixteenth century a number of persons named Lopez, possibly all of the same family, took refuge in England, the best known of them being Rodrigo López, physician to Queen Elizabeth I, and who is said by some commentators to have been the inspiration for Shylock.[22]

England also saw converts such as Immanuel Tremellius and Philip Ferdinand. Jewish visitors included Joachim Gaunse, who introduced new methods of mining into England and there are records of visits from Jews named Alonzo de Herrera and Simon Palache in 1614. The writings of John Weemes in the 1630s provided a positive view of the resettlement of Jews in England, effected in 1657.[23]

Planned apology[]

In July 2021, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, announced that the Church of England will in 2022 offer a formal “act of repentance”, on the 800th anniversary of the Synod of Oxford, which passed a set of laws that restricted Jews’ rights to engage with Christians in England that led to the expulsion of 1290. Historically, the Synod predated Church of England’s creation in 1534.[24]

See also[]

- Aliens Act 1905

- History of the Jews in England

- History of the Jews in England (1066–1290)

- History of the Marranos in England

- Resettlement of the Jews in England

- Menasseh Ben Israel (1604–1657)

- Jewish Naturalization Act 1753

- Emancipation of the Jews in England

- Early English Jewish literature

- History of the Jews in Scotland

- History of the Jews in Wales

- History of the Jews in Ireland

- Alhambra Decree

- Expulsion of the Moriscos

- Edict of Fontainebleau

- Robert de Reddinge

- 1731 Expulsion of Protestants from Salzburg

Notes[]

- ^ Readmission of Jews to Britain in 1656, BBC

- ^ Paul Johnson, A History of the Jews, p. 208

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Jacobs 1903

- ^ Glassman 1975, p. 14.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rubinstein 1996, p. 36.

- ^ Reuveni, Gideon; Wobick-segev, Sarah (2010). The Economy in Jewish History: New Perspectives on the Interrelationship Between Ethnicity and Economic Life. Berghahn Books. p. 8. ISBN 9781845459864.

- ^ Parkes 1976, p. 303.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rubinstein 1996, p. 37.

- ^ Glassman 1975, p. 17.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rubinstein 1996, p. 39.

- ^ Glassman 1975, p. 16.

- ^ "Jewish History 1220-1229". www.jewishhistory.org.il.

- ^ Prestwich 1997, p. 345

- ^ Prestwich 1997, p. 306.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Prestwich 1997, p. 346

- ^ Prestwich 1997, p. 307

- ^ Jump up to: a b Prestwich 1997, p. 343.

- ^ On the Hebrew calendar, this date was 9 Av (Tisha B'Av) 5050.

- ^ Mundill, Robin R. (2002). England's Jewish Solution: Experiment and Expulsion, 1262–1290. Cambridge University Press. p. 27. ISBN 0-521-52026-6.

- ^ Craik, George Lillie, (1847), "Sketches of Popular Tulmuts", c. Cox, p.21.

- ^ Rotuli Parliamentorum ii. 332a.

- ^ Greenblatt, S. (2004), Will In The World: How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare, New York: W.W. Norton, ISBN 0-393-05057-2

- ^ Bowman, John (1 January 1949). "A Seventeenth Century Bill of "Rights" for Jews". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 39 (4): 379–389. doi:10.2307/1453260. JSTOR 1453260.

- ^ The church apologizes for expulsion 800 years later - repenting for sins

References[]

- Adler, Michael (1939), Jews of Medieval England, Edward Goldston.

- Glassman, Bernard (1975), Anti-Semitic Stereotypes Without Jews: Images of the Jews in England 1290–1700, Wayne State University Press, ISBN 0-8143-1545-3.

- Parkes, James (1976), The Jew in the Medieval Community, Hermon Press, ISBN 0-87203-059-8.

- Powicke, Sir Maurice (1953), The Thirteenth Century, 1216–1307, Clarendon Press.

- Prestwich, Michael (1997), Edward I, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-07157-4

- Rubinstein, W. D. (1996), A History of the Jews in the English-Speaking World: Great Britain, Macmillan Press, ISBN 0-333-55833-2.

Jacobs, Joseph (1903). "England". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. 5. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. pp. 161–174.

Jacobs, Joseph (1903). "England". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. 5. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. pp. 161–174.

External links[]

- 1290 in England

- 13th-century Judaism

- Antisemitism in England

- Edicts

- Edward I of England

- Expulsions of Jews

- Jewish English history

- Medieval Jewish history

- Religious expulsion orders

- Sephardi Jews topics

- Ethnic cleansing in Europe