Emor

Emor (Hebrew: אֱמֹר — Hebrew for "speak," the fifth word, and the first distinctive word, in the parashah) is the 31st weekly Torah portion (Hebrew: פָּרָשָׁה, parashah) in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the eighth in the Book of Leviticus. The parashah describes purity rules for priests (Hebrew: כֹּהֲנִים, Kohanim), recounts the holy days, describes the preparations for the lights and bread in the sanctuary, and tells the story of a blasphemer and his punishment. The parashah constitutes Leviticus 21:1–24:23. It has the most verses (but not the most letters or words) of any of the weekly Torah portions in the Book of Leviticus, and is made up of 6,106 Hebrew letters, 1,614 Hebrew words, 124 verses and 215 lines in a Torah Scroll (Hebrew: סֵפֶר תּוֹרָה, Sefer Torah). (Parashah Vayikra has the most letters and words of any weekly Torah portion in Leviticus.)[1]

Jews generally read it in early May, or rarely in late April.[2] Jews also read parts of the parashah, Leviticus 22:26–23:44, as the initial Torah readings for the second day of Passover and the first and second days of Sukkot.

Readings[]

In traditional Sabbath Torah reading, the parashah is divided into seven readings, or Hebrew: עליות, aliyot.[3]

First reading — Leviticus 21:1–15[]

In the first reading (Hebrew: עליה, aliyah), God told Moses to tell the priests the priestly laws.[4] None were to come in contact with a dead body except for that of his closest relatives: his parent, child, brother, or virgin sister.[5] They were not to shave any part of their heads or the side-growth of their beards or gash their flesh.[6] They were not to marry a harlot or divorcee.[7] The daughter of a priest who became a harlot was to be executed.[8] The High Priest was not to bare his head or rend his vestments.[9] He was not to come near any dead body, even that of his father or mother.[10] He was to marry only a virgin of his own kin.[11]

Second reading — Leviticus 21:16–22:16[]

In the second reading (Hebrew: עליה, aliyah), no disabled priest could offer sacrifices.[12] He could eat the meat of sacrifices, but could not come near the altar.[13] No priest who had become unclean could eat the meat of sacrifices.[14] A priest could not share his sacrificial meat with lay persons, persons whom the priest had hired, or the priest's married daughters. However, the priest could share that meat with his slaves and widowed or divorced daughters, if those daughters had no children.[15]

Third reading — Leviticus 22:17–33[]

In the third reading (Hebrew: עליה, aliyah), only animals without defect qualified for sacrifice.[16]

Fourth reading — Leviticus 23:1–22[]

In the fourth reading (Hebrew: עליה, aliyah), God told Moses to instruct the Israelites to proclaim the following sacred occasions:

- Shabbat (Sabbath) on the seventh day[17]

- Pesach (Passover) for 7 days beginning at twilight of the 14th day of the first month[18]

- Shavuot (Feast of Weeks) 50 days later[19]

Fifth reading — Leviticus 23:23–32[]

The fifth reading (Hebrew: עליה, aliyah) continues the sacred occasions:

- Rosh Hashanah (New Year) on the first day of the seventh month[20]

- Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement) on the 10th day of the seventh month[21]

Sixth reading — Leviticus 23:33–44[]

The sixth reading (Hebrew: עליה, aliyah), concludes the sacred occasions:

- Sukkot (Tabernacles) for 8 days beginning on the 15th day of the seventh month[22]

Seventh reading — Leviticus 24:1–23[]

In the seventh reading (Hebrew: עליה, aliyah), God told Moses to command the Israelites to bring clear olive oil for lighting the lamps of the Tabernacle regularly, from evening to morning.[23] And God called for baking twelve loaves to be placed in the Tabernacle every Sabbath, and thereafter given to the priests, who were to eat them in the sacred precinct.[24]

A man with an Israelite mother (from the tribe of Dan) and an Egyptian father got in a fight, and pronounced God's Name in blasphemy.[25] The people brought him to Moses and placed him in custody until God's decision should be made clear.[26] God told Moses to take the blasphemer outside the camp where all who heard him were to lay their hands upon his head, and the whole community was to stone him, and they did so.[27] God instructed that anyone who blasphemed God was to be put to death.[28] Anyone who murdered any human being was to be put to death.[29] One who killed a beast was to make restitution.[30] And anyone who maimed another person was to pay proportionately (in what has been called lex talionis).[31]

Readings according to the triennial cycle[]

Jews who read the Torah according to the triennial cycle of Torah reading read the parashah according to the following schedule:[32]

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020, 2023 . . . | 2021, 2024 . . . | 2022, 2025 . . . | |

| Reading | 21:1–22:16 | 22:17–23:22 | 23:23–24:23 |

| 1 | 21:1–6 | 22:17–20 | 23:23–25 |

| 2 | 21:7–12 | 22:21–25 | 23:26–32 |

| 3 | 21:13–15 | 22:26–33 | 23:33–44 |

| 4 | 21:16–24 | 23:1–3 | 24:1–4 |

| 5 | 22:1–9 | 23:4–8 | 24:5–9 |

| 6 | 22:10–12 | 23:9–14 | 24:10–12 |

| 7 | 22:13–16 | 23:15–22 | 24:13–23 |

| Maftir | 22:13–16 | 23:19–22 | 24:21–23 |

In ancient parallels[]

The parashah has parallels in these ancient sources:

Leviticus chapter 24[]

The Code of Hammurabi contained precursors of the law of "an eye for an eye" in Leviticus 24:19–21. The Code of Hammurabi provided that if a man destroyed the eye of another man, they were to destroy his eye. If one broke a man's bone, they were to break his bone. If one destroyed the eye of a commoner or broke the bone of a commoner, he was to pay one mina of silver. If one destroyed the eye of a slave or broke a bone of a slave, he was to pay one-half the slave's price. If a man knocked out a tooth of a man of his own rank, they were to knock out his tooth. If one knocked out a tooth of a commoner, he was to pay one-third of a mina of silver. If a man struck a man's daughter and brought about a miscarriage, he was to pay 10 shekels of silver for her miscarriage. If the woman died, they were to put the man's daughter to death. If a man struck the daughter of a commoner and brought about a miscarriage, he was to pay five shekels of silver. If the woman died, he was to pay one-half of a mina of silver. If he struck a man's female slave and brought about a miscarriage, he was to pay two shekels of silver. If the female slave died, he was to pay one-third of a mina of silver.[33]

In inner-Biblical interpretation[]

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these Biblical sources:[34]

Leviticus chapter 21[]

Corpse contamination[]

In Leviticus 21:1–5, God instructed Moses to direct the priests not to allow themselves to become defiled by contact with the dead, except for a mother, father, son, daughter, brother, or unmarried sister. And the priests were not to engage in mourning rituals of making baldness upon their heads, shaving off the corners of their beards, or cutting their flesh. This prohibition of corpse contamination is one of a series of passages in the Hebrew Bible setting out the teaching that contact with the dead is antithetical to purity.

In Numbers 5:1–4, God instructed Moses to command the Israelites to put out of the camp every person defiled by contact with the dead, so that they would not defile their camps, in the midst of which God dwelt.

Numbers 19 sets out a procedure for a red cow mixture for decontamination from corpse contamination.

Deuteronomy 26:13–14 instructed Israelites to announce before God that they had not eaten from the tithe in mourning, nor put away any of it while unclean, nor given any of it to the dead.

In Ezekiel 43:6–9, the prophet Ezekiel cites the burial of kings within the Temple as one of the practices that defiled the Temple and cause God to abandon it.

In the Hebrew Bible, uncleanness has a variety of associations. Leviticus 11:8, 11; 21:1–4, 11; and Numbers 6:6–7; and 19:11–16; associate it with death. And perhaps similarly, Leviticus 13–14 associates it with skin disease. Leviticus 12 associates it with childbirth. Leviticus 15 associates it with various sexuality-related events. And Jeremiah 2:7, 23; 3:2; and 7:30; and Hosea 6:10 associate it with contact with the worship of alien gods.

Leviticus chapter 22[]

In Malachi 1:6–10, the prophet berated priests who despised God's name by offering blind, lame, and sick animals for sacrifice in violation of Leviticus 22:22. The prophet asked whether such presents would please an earthly governor.

Leviticus chapter 23[]

The Sabbath[]

Leviticus 23:1–3 refers to the Sabbath. Commentators note that the Hebrew Bible repeats the commandment to observe the Sabbath 12 times.[35]

Genesis 2:1–3 reports that on the seventh day of Creation, God finished God's work, rested, and blessed and hallowed the seventh day.

The Sabbath is one of the Ten Commandments. Exodus 20:7–10[36] commands that one remember the Sabbath day, keep it holy, and not do any manner of work or cause anyone under one's control to work, for in six days God made heaven and earth and rested on the seventh day, blessed the Sabbath, and hallowed it. Deuteronomy 5:11–14[37] commands that one observe the Sabbath day, keep it holy, and not do any manner of work or cause anyone under one's control to work — so that one's subordinates might also rest — and remember that the Israelites were servants in the land of Egypt, and God brought them out with a mighty hand and by an outstretched arm.

In the incident of the manna (Hebrew: מָן, man) in Exodus 16:22–30, Moses told the Israelites that the Sabbath is a solemn rest day; prior to the Sabbath one should cook what one would cook, and lay up food for the Sabbath. And God told Moses to let no one go out of one's place on the seventh day.

In Exodus 31:12–17, just before giving Moses the second Tablets of Stone, God commanded that the Israelites keep and observe the Sabbath throughout their generations, as a sign between God and the children of Israel forever, for in six days God made heaven and earth, and on the seventh day God rested.

In Exodus 35:1–3, just before issuing the instructions for the Tabernacle, Moses again told the Israelites that no one should work on the Sabbath, specifying that one must not kindle fire on the Sabbath.

In Leviticus 23:1–3, God told Moses to repeat the Sabbath commandment to the people, calling the Sabbath a holy convocation.

The prophet Isaiah taught in Isaiah 1:12–13 that iniquity is inconsistent with the Sabbath. In Isaiah 58:13–14, the prophet taught that if people turn away from pursuing or speaking of business on the Sabbath and call the Sabbath a delight, then God will make themride upon the high places of the earth and will feed them with the heritage of Jacob. And in Isaiah 66:23, the prophet taught that in times to come, from one Sabbath to another, all people will come to worship God.

The prophet Jeremiah taught in Jeremiah 17:19–27 that the fate of Jerusalem depended on whether the people obstained from work on the Sabbath, refraining from carrying burdens outside their houses and through the city gates.

The prophet Ezekiel told in Ezekiel 20:10–22 how God gave the Israelites God's Sabbaths, to be a sign between God and them, but the Israelites rebelled against God by profaning the Sabbaths, provoking God to pour out God's fury upon them, but God stayed God's hand.

In Nehemiah 13:15–22, Nehemiah told how he saw some treading winepresses on the Sabbath, and others bringing all manner of burdens into Jerusalem on the Sabbath day, so when it began to be dark before the Sabbath, he commanded that the city gates be shut and not opened till after the Sabbath and directed the Levites to keep the gates to sanctify the Sabbath.

Passover[]

Leviticus 23:4–8 refers to the Festival of Passover. In the Hebrew Bible, Passover is called:

- Passover (Hebrew: פֶּסַח, Pesach);[38]

- The Feast of Unleavened Bread (Hebrew: חַג הַמַּצּוֹת, Chag haMatzot);[39] and

- A holy convocation or a solemn assembly. (Hebrew: מִקְרָא-קֹדֶשׁ, mikrah kodesh)[40]

Some explain the double nomenclature of "Passover" and "Feast of Unleavened Bread" as referring to two separate feasts that the Israelites combined sometime between the Exodus and when the Biblical text became settled.[41] Exodus 34:18–20 and Deuteronomy 15:19–16:8 indicate that the dedication of the firstborn also became associated with the festival.

Some believe that the Feast of Unleavened Bread was an agricultural festival at which the Israelites celebrated the beginning of the grain harvest. Moses may have had this festival in mind when in Exodus 5:1 and 10:9 he petitioned Pharaoh to let the Israelites go to celebrate a feast in the wilderness.[42]

"Passover," on the other hand, was associated with a thanksgiving sacrifice of a lamb, also called "the Passover," "the Passover lamb," or "the Passover offering."[43]

Exodus 12:5–6, Leviticus 23:5, and Numbers 9:3 and 5, and 28:16 direct Passover to take place on the evening of the fourteenth of Aviv (Nisan in the Hebrew calendar after the Babylonian captivity). Joshua 5:10, Ezekiel 45:21, Ezra 6:19, and 2 Chronicles 35:1 confirm that practice. Exodus 12:18–19, 23:15, and 34:18, Leviticus 23:6, and Ezekiel 45:21 direct the Feast of Unleavened Bread to take place over seven days and Leviticus 23:6 and Ezekiel 45:21 direct that it begin on the fifteenth of the month. Some believe that the propinquity of the dates of the two festivals led to their confusion and merger.[42]

Exodus 12:23 and 27 link the word "Passover" (Hebrew: פֶּסַח, Pesach) to God's act to "pass over" (Hebrew: פָסַח, pasach) the Israelites' houses in the plague of the firstborn. In the Torah, the consolidated Passover and Feast of Unleavened Bread thus commemorate the Israelites' liberation from Egypt.[44]

The Hebrew Bible frequently notes the Israelites' observance of Passover at turning points in their history. Numbers 9:1–5 reports God's direction to the Israelites to observe Passover in the wilderness of Sinai on the anniversary of their liberation from Egypt. Joshua 5:10–11 reports that upon entering the Promised Land, the Israelites kept the Passover on the plains of Jericho and ate unleavened cakes and parched corn, produce of the land, the next day. 2 Kings 23:21–23 reports that King Josiah commanded the Israelites to keep the Passover in Jerusalem as part of Josiah's reforms, but also notes that the Israelites had not kept such a Passover from the days of the Biblical judges nor in all the days of the kings of Israel or the kings of Judah, calling into question the observance of even Kings David and Solomon. The more reverent 2 Chronicles 8:12–13, however, reports that Solomon offered sacrifices on the festivals, including the Feast of Unleavened Bread. And 2 Chronicles 30:1–27 reports King Hezekiah's observance of a second Passover anew, as sufficient numbers of neither the priests nor the people were prepared to do so before then. And Ezra 6:19–22 reports that the Israelites returned from the Babylonian captivity observed Passover, ate the Passover lamb, and kept the Feast of Unleavened Bread seven days with joy.

Shavuot[]

Leviticus 23:15–21 refers to the Festival of Shavuot. In the Hebrew Bible, Shavuot is called:

- The Feast of Weeks (Hebrew: חַג שָׁבֻעֹת, Chag Shavuot);[45]

- The Day of the First-fruits (Hebrew: יוֹם הַבִּכּוּרִים, Yom haBikurim);[46]

- The Feast of Harvest (Hebrew: חַג הַקָּצִיר, Chag haKatzir);[47] and

- A holy convocation (Hebrew: מִקְרָא-קֹדֶשׁ, mikrah kodesh).[48]

Exodus 34:22 associates Shavuot with the first-fruits (Hebrew: בִּכּוּרֵי, bikurei) of the wheat harvest.[49] In turn, Deuteronomy 26:1–11 set out the ceremony for the bringing of the first fruits.

To arrive at the correct date, Leviticus 23:15 instructs counting seven weeks from the day after the day of rest of Passover, the day that they brought the sheaf of barley for waving. Similarly, Deuteronomy 16:9 directs counting seven weeks from when they first put the sickle to the standing barley.

Leviticus 23:16–19 sets out a course of offerings for the fiftieth day, including a meal-offering of two loaves made from fine flour from the first-fruits of the harvest; burnt-offerings of seven lambs, one bullock, and two rams; a sin-offering of a goat; and a peace-offering of two lambs. Similarly, Numbers 28:26–30 sets out a course of offerings including a meal-offering; burnt-offerings of two bullocks, one ram, and seven lambs; and one goat to make atonement. Deuteronomy 16:10 directs a freewill-offering in relation to God's blessing.

Leviticus 23:21 and Numbers 28:26 ordain a holy convocation in which the Israelites were not to work.

2 Chronicles 8:13 reports that Solomon offered burnt-offerings on the Feast of Weeks.

Rosh Hashanah[]

Leviticus 23:23–25 refers to the Festival of Rosh Hashanah. In the Hebrew Bible, Rosh Hashanah is called:

- a memorial proclaimed with the blast of horns (Hebrew: זִכְרוֹן תְּרוּעָה, Zichron Teruah);[50]

- a day of blowing the horn (Hebrew: יוֹם תְּרוּעָה, Yom Teruah);[51] and

- a holy convocation (Hebrew: מִקְרָא-קֹדֶשׁ, mikrah kodesh)[52]

Although Exodus 12:2 instructs that the spring month of Aviv (since the Babylonian captivity called Nisan) "shall be the first month of the year," Exodus 23:16 and 34:22 also reflect an "end of the year" or a "turn of the year" in the autumn harvest month of Tishrei.

Leviticus 23:23–25 and Numbers 29:1–6 both describe Rosh Hashanah as an holy convocation, a day of solemn rest in which no servile work is to be done, involving the blowing of horns and an offering to God.

Ezekiel 40:1 speaks of "in the beginning of the year" (Hebrew: בְּרֹאשׁ הַשָּׁנָה, b'Rosh HaShanah) in Tishrei, although the Rabbis traditionally interpreted Ezekiel to refer to Yom Kippur.

Ezra 3:1–3 reports that in the Persian era, when the seventh month came, the Israelites gathered together in Jerusalem, and the priests offered burnt-offerings to God, morning and evening, as written in the Law of Moses.

Nehemiah 8:1–4 reports that it was on Rosh Hashanah (the first day of the seventh month) that all the Israelites gathered together before the water gate and Ezra the scribe read the Law from early morning until midday. And Nehemiah, Ezra, and the Levites told the people that the day was holy to the Lord their God; they should neither mourn nor weep; but they should go their way, eat the fat, drink the sweet, and send portions to those who had nothing.[53]

Psalm 81:4–5 likely refers to Rosh Hashanah when it enjoins, "Blow the horn at the new moon, at the full moon of our feast day. For it is a statute for Israel, an ordinance of the God of Jacob."

Yom Kippur[]

Leviticus 23:26–32 refers to the Festival of Yom Kippur. In the Hebrew Bible, Yom Kippur is called:

- the Day of Atonement (Hebrew: יוֹם הַכִּפֻּרִים, Yom HaKippurim)[54] or a Day of Atonement (Hebrew: יוֹם כִּפֻּרִים, Yom Kippurim);[55]

- a Sabbath of solemn rest (Hebrew: שַׁבַּת שַׁבָּתוֹן, Shabbat Shabbaton);[56] and

- a holy convocation (Hebrew: מִקְרָא-קֹדֶשׁ, mikrah kodesh).[57]

Much as Yom Kippur, on the 10th of the month of Tishrei, precedes the Festival of Sukkot, on the 15th of the month of Tishrei, Exodus 12:3–6 speaks of a period starting on the 10th of the month of Nisan preparatory to the Festival of Passover, on the 15th of the month of Nisan.

Leviticus 16:29–34 and 23:26–32 and Numbers 29:7–11 present similar injunctions to observe Yom Kippur. Leviticus 16:29 and 23:27 and Numbers 29:7 set the Holy Day on the tenth day of the seventh month (Tishrei). Leviticus 16:29 and 23:27 and Numbers 29:7 instruct that "you shall afflict your souls." Leviticus 23:32 makes clear that a full day is intended: "you shall afflict your souls; in the ninth day of the month at evening, from evening to evening." And Leviticus 23:29 threatens that whoever "shall not be afflicted in that same day, he shall be cut off from his people." Leviticus 16:29 and Leviticus 23:28 and Numbers 29:7 command that you "shall do no manner of work." Similarly, Leviticus 16:31 and 23:32 call it a "Sabbath of solemn rest." And in 23:30, God threatens that whoever "does any manner of work in that same day, that soul will I destroy from among his people." Leviticus 16:30, 16:32–34, and 23:27–28, and Numbers 29:11 describe the purpose of the day to make atonement for the people. Similarly, Leviticus 16:30 speaks of the purpose "to cleanse you from all your sins," and Leviticus 16:33 speaks of making atonement for the most holy place, the tent of meeting, the altar; and the priests. Leviticus 16:29 instructs that the commandment applies both to "the home-born" and to "the stranger who sojourns among you." Leviticus 16:3–25 and 23:27 and Numbers 29:8–11 command offerings to God. And Leviticus 16:31 and 23:31 institute the observance as "a statute forever."

Leviticus 16:3–28 sets out detailed procedures for the priest's atonement ritual.

Leviticus 25:8–10 instructs that after seven Sabbatical years, on the Jubilee year, on the day of atonement, the Israelites were to proclaim liberty throughout the land with the blast of the horn and return every man to his possession and to his family.

In Isaiah 57:14–58:14, the Haftarah for Yom Kippur morning, God describes "the fast that I have chosen [on] the day for a man to afflict his soul." Isaiah 58:3–5 make clear that "to afflict the soul" was understood as fasting. But Isaiah 58:6–10 goes on to impress that "to afflict the soul," God also seeks acts of social justice: "to loose the fetters of wickedness, to undo the bands of the yoke," "to let the oppressed go free," "to give your bread to the hungry, and . . . bring the poor that are cast out to your house," and "when you see the naked, that you cover him."

Sukkot[]

And Leviticus 23:33–42 refers to the Festival of Sukkot. In the Hebrew Bible, Sukkot is called:

- The Feast of Tabernacles (or Booths);[58]

- The Feast of Ingathering;[59]

- The Feast or the festival;[60]

- The Feast of the Lord;[61]

- The festival of the seventh month;[62] and

- A holy convocation or a sacred occasion. (Hebrew: מִקְרָא-קֹדֶשׁ, mikrah kodesh).[63]

Sukkot's agricultural origin is evident from the name The Feast of Ingathering, from the ceremonies accompanying it, and from the season and occasion of its celebration: "At the end of the year when you gather in your labors out of the field";[64] "after you have gathered in from your threshing-floor and from your winepress."[65] It was a thanksgiving for the fruit harvest.[66] And in what may explain the festival's name, Isaiah reports that grape harvesters kept booths in their vineyards.[67] Coming as it did at the completion of the harvest, Sukkot was regarded as a general thanksgiving for the bounty of nature in the year that had passed.

Sukkot became one of the most important feasts in Judaism, as indicated by its designation as the Feast of the Lord[68] or simply "the Feast."[60] Perhaps because of its wide attendance, Sukkot became the appropriate time for important state ceremonies. Moses instructed the children of Israel to gather for a reading of the Law during Sukkot every seventh year.[69] King Solomon dedicated the Temple in Jerusalem on Sukkot.[70] And Sukkot was the first sacred occasion observed after the resumption of sacrifices in Jerusalem after the Babylonian captivity.[71]

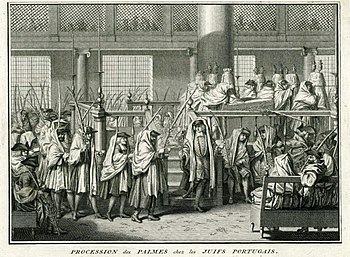

In the time of Nehemiah, after the Babylonian captivity, the Israelites celebrated Sukkot by making and dwelling in booths, a practice of which Nehemiah reports: "the Israelites had not done so from the days of Joshua."[72] In a practice related to that of the Four Species, Nehemiah also reports that the Israelites found in the Law the commandment that they "go out to the mountains and bring leafy branches of olive trees, pine trees, myrtles, palms and [other] leafy trees to make booths."[73] In Leviticus 23:40, God told Moses to command the people: "On the first day you shall take the product of hadar trees, branches of palm trees, boughs of leafy trees, and willows of the brook," and "You shall live in booths seven days; all citizens in Israel shall live in booths, in order that future generations may know that I made the Israelite people live in booths when I brought them out of the land of Egypt."[74] The book of Numbers, however, indicates that while in the wilderness, the Israelites dwelt in tents.[75] Some secular scholars consider Leviticus 23:39–43 (the commandments regarding booths and the four species) to be an insertion by a late redactor.[76]

Jeroboam son of Nebat, King of the northern Kingdom of Israel, whom 1 Kings 13:33 describes as practicing "his evil way," celebrated a festival on the fifteenth day of the eighth month, one month after Sukkot, "in imitation of the festival in Judah."[77] "While Jeroboam was standing on the altar to present the offering, the man of God, at the command of the Lord, cried out against the altar" in disapproval.[78]

According to the prophet Zechariah, in the messianic era, Sukkot will become a universal festival, and all nations will make pilgrimages annually to Jerusalem to celebrate the feast there.[79]

Leviticus chapter 24[]

In three separate places — Exodus 21:22–25; Leviticus 24:19–21; and Deuteronomy 19:16–21 — the Torah sets forth the law of "an eye for an eye."

In early nonrabbinic interpretation[]

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these early nonrabbinic sources:[80]

Leviticus chapter 23[]

1 Maccabees 2:27–38 told how in the 2nd century BCE, many followers of the pious Jewish priest Mattathias rebelled against the Seleucid king Antiochus IV Epiphanes. Antiochus's soldiers attacked a group of them on the Sabbath, and when the Pietists failed to defend themselves so as to honor the Sabbath (commanded in, among other places, Leviticus 23:1–3), a thousand died. 1 Maccabees 2:39–41 reported that when Mattathias and his friends heard, they reasoned that if they did not fight on the Sabbath, they would soon be destroyed. So they decided that they would fight against anyone who attacked them on the Sabbath.[81]

A letter from Simon bar Kokhba written during the Bar Kokhba revolt found in the Cave of Letters includes commands to a subordinate to assemble components of the lulav and etrog, apparently so as to celebrate Sukkot.[82]

In classical rabbinic interpretation[]

The parashah is discussed in these rabbinic sources from the era of the Mishnah and the Talmud:[83]

Leviticus chapter 21[]

Rabbi Tanhum son of Rabbi Hannilai taught that Leviticus 21 was one of two sections in the Torah (along with Numbers 19, on the Red Cow) that Moses gave us in writing that are both pure, dealing with the law of purity. Rabbi Tanhum taught that they were given on account of the tribe of Levi, of whom it is written (in Malachi 3:3), "he [God's messenger] shall purify the sons of Levi and purge them."[84]

Rabbi Levi taught that God gave the section of the priests in Leviticus 21 on the day that the Israelites set up the Tabernacle. Rabbi Johanan said in the name of Rabbi Bana'ah that the Torah was transmitted in separate scrolls, as Psalm 40:8 says, "Then said I, 'Lo I am come, in the roll of the book it is written of me.'" Rabbi Simeon ben Lakish (Resh Lakish), however, said that the Torah was transmitted in its entirety, as Deuteronomy 31:26, "Take this book of the law." The Gemara reported that Rabbi Johanan interpreted Deuteronomy 31:26, "Take this book of the law," to refer to the time after the Torah had been joined together from its several parts. And the Gemara suggested that Resh Lakish interpreted Psalm 40:8, "in a roll of the book written of me," to indicate that the whole Torah is called a "roll," as Zechariah 5:2 says, "And he said to me, 'What do you see?' And I answered, 'I see a flying roll.'" Or perhaps, the Gemara suggested, it is called "roll" for the reason given by Rabbi Levi, who said that God gave eight sections of the Torah, which Moses then wrote on separate rolls, on the day on which the Tabernacle was set up. They were: the section of the priests in Leviticus 21, the section of the Levites in Numbers 8:5–26 (as the Levites were required for the service of song on that day), the section of the unclean (who would be required to keep the Passover in the second month) in Numbers 9:1–14, the section of the sending of the unclean out of the camp (which also had to take place before the Tabernacle was set up) in Numbers 5:1–4, the section of Leviticus 16:1–34 (dealing with Yom Kippur, which Leviticus 16:1 states was transmitted immediately after the death of Aaron's two sons), the section dealing with the drinking of wine by priests in Leviticus 10:8–11, the section of the lights of the menorah in Numbers 8:1–4, and the section of the red heifer in Numbers 19 (which came into force as soon as the Tabernacle was set up).[85]

The Gemara noted the apparently superfluous "say to them" in Leviticus 21:1 and reported an interpretation that the language meant that adult Kohanim must warn their children away from becoming contaminated by contact with a corpse. But then the Gemara stated that the correct interpretation was that the language meant to warn adults to avoid contaminating the children through their own contact.[86] Elsewhere, the Gemara used the redundancy to teach that a priest could also defile himself by contact with the greater part of the bodily frame of his sister's corpse or the majority of its bones.[87] A Midrash explained the redundancy by teaching that the first expression of "speak" indicated that a priest may defile himself on account of an unattended corpse (meit mitzvah), while the second expression "say" indicated that he may not defile himself on account of any other corpse.[88] Another Midrash explained the redundancy to teach that for the celestial beings, where the Evil Inclination (Hebrew: יֵצֶר הַרַע, yeitzer hara) is non-existent, one utterance is sufficient, but with terrestrial beings, in whom the Evil Inclination exists, at least two utterances are required.[89]

The Mishnah taught that the commandment of Leviticus 21:1 for Kohanim not to become ritually impure for the dead is one of only three exceptions to the general rule that every commandment that is a prohibition (whether time-dependent or not) governs both men and women (as the prohibition of Leviticus 21:1 on Kohanim applies only to men). The other exceptions are the commandments of Leviticus 19:27 not to round off the side-growth of one's head and not to destroy the corners of one's beard (which likewise apply only to men).[90]

The Mishnah employed the prohibitions of Leviticus 21:1 and 23:7 to imagine how one could with one action violate up to nine separate commandments. One could (1) plow with an ox and a donkey yoked together (in violation of Deuteronomy 22:10) (2 and 3) that are two animals dedicated to the sanctuary, (4) plowing mixed seeds sown in a vineyard (in violation of Deuteronomy 22:9), (5) during a Sabbatical year (in violation of Leviticus 25:4), (6) on a Festival-day (in violation of, for example, Leviticus 23:7), (7) when the plower is a priest (in violation of Leviticus 21:1) and (8) a Nazirite (in violation of Numbers 6:6) plowing in a contaminated place. Chananya ben Chachinai said that the plower also may have been wearing a garment of wool and linen (in violation of Leviticus 19:19 and Deuteronomy 22:11). They said to him that this would not be in the same category as the other violations. He replied that neither is the Nazirite in the same category as the other violations.[91]

The Gemara taught that where Leviticus 21:1–2 prohibited the priest from defiling himself by contact with the dead "except for his flesh, that is near to him" the words "his flesh" meant to include his wife in the exception.[92]

Reading Leviticus 21:3, "And for his sister a virgin, that is near to him, who has had no husband, for her may he become impure," Rabbi Ishmael taught that it was optional for a priest to participate in his sister's burial. But Rabbi Akiva said that it was mandatory for him to do so.[93]

The Babylonian Talmud reported that the Sages taught that a mourner must mourn for all the relatives for whom Leviticus 21:1–3 teaches that a priest became impure — his wife, father, mother, son, daughter, and brother and unmarried sister from the same father. The Sages added to this list his brother and unmarried sister from the same mother, and his married sister, whether from the same father or from the same mother.[94]

The Mishnah interpreted Leviticus 21:7 to teach that both acting and retired High Priests had to marry a virgin and were forbidden to marry a widow. And the Mishnah interpreted Leviticus 21:1–6 to teach that both could not defile themselves for the dead bodies of their relatives, could not let their hair grow wild in mourning, and could not rend their clothes as other Jews did in mourning.[95] The Mishnah taught that while an ordinary priest in mourning rent his garments from above, a High Priest rent his garments from below. And the Mishnah taught that on the day of a close relative's death, the High Priest could still offer sacrifices but could not eat of the sacrificial meat, while under those circumstances an ordinary priest could neither offer sacrifices nor eat sacrificial meat.[96]

Rabbi Hiyya bar Abba cited Leviticus 21:8 to support the proposition that a Kohen should be called up first to read the law, for the verse taught to give Kohanim precedence in every matter of sanctity. And a Baraita was taught in the school of Rabbi Ishmael that Leviticus 21:8 meant that Jews should give Kohanim precedence in every matter of sanctity, including speaking first at every assembly, saying grace first, and choosing his portion first when an item was to be divided.[97] The Mishnah recognized the status of the Kohanim over Levites, Levites over Israelites, and Israelites over those born from forbidden relationships, but only when they were equal in all other respects. The Mishnah taught that a learned child of forbidden parents took precedence over an ignorant High Priest.[98]

The Gemara interpreted the law of the Kohen's adulterous daughter in Leviticus 21:9 in Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 49b–52a.[99]

Interpreting the words "the priest that is highest among his brethren" in Leviticus 21:10, a Midrash taught that the High Priest was superior in five things: wisdom, strength, beauty, wealth, and age.[100]

The Sifre compared the prohibition of a nazirite having contact with dead bodies in Numbers 6:6–7 with the similar prohibition of a High Priest having contact with dead bodies in Leviticus 21:11. And the Sifre reasoned that just as the High Priest was required nonetheless to become unclean to see to the burial of a neglected corpse (met mitzvah), so too was the nazirite required to become unclean to see to the burial of a neglected corpse.[101]

Chapter 7 of Tractate Bekhorot in the Mishnah and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of blemishes that prohibited a priest from performing sacrifices in Leviticus 21:16–23.[102]

The Mishnah taught that a disability that did not disqualify priests disqualified Levites, and a disability that did not disqualify Levites disqualified priests.[103] The Gemara explained that our Rabbis taught that Leviticus 21:17 disqualified priests by reason of a bodily blemish, and not by reason of age; and Levites were disqualified by age, for they were qualified for service only from the age of 30 to 50, and not by bodily blemish. It follows, therefore, that the disability that does not disqualify priests disqualifies Levites, and the disability that does not disqualify Levites disqualifies priests. The Gemara taught that we know this from a Baraita in which our Rabbis noted that Numbers 8:24 says: "This is that which pertains to the Levites." From Numbers 8:25, "And from the age of 50 years they shall return from the service of the work," we know that Levites were disqualified by age. One might have argued that they were disqualified by bodily blemish too; thus, if priests who were not disqualified by age were nevertheless disqualified by bodily blemish, Levites who were disqualified by age should surely have been disqualified by bodily blemish. Numbers 8:24 therefore says: "This is that which pertains to the Levites," to instruct that "this", that is, age, only disqualifies Levites, but nothing else disqualifies them. One might also have argued that priests were disqualified by age too; thus, if Levites who were not disqualified by bodily blemish were nevertheless disqualified by age, priests who were disqualified by bodily blemish should surely have been disqualified by age. Numbers 8:24 therefore says: "Which pertains to the Levites", and not "to the priests". One might further have supposed that the rule that Levites were disqualified by age obtained even at Shiloh and at the Temple at Jerusalem, where the Levites sang in the choir and guarded the doors of the Temple. Numbers 4:47 therefore says: "To do the work of service and the work of bearing burdens," to instruct that God ordained this rule disqualifying Levites by age only when the work was that of bearing burdens upon the shoulder, the service of the Tabernacle in the wilderness, and not at the Temple at Jerusalem.[104] Similarly, the Sifre taught that years invalidated in the case of Levites but not in the case of the priesthood. For prior to the entry into the Land of Israel, the Levites were valid from the age of 30 to the age of 50, while the priests were valid from puberty until the end of their lives. But once they came into the Land, the Levites were invalidated only by losing their voice.[105] Elsewhere, the Sifre read Numbers 8:25–26, "and shall serve no more; but shall minister with their brethren in the tent of meeting, to keep the charge, but they shall do no manner of service," to teach that the Levite went back to the work of locking the doors and carrying out the tasks assigned to the sons of Gershom.[106]

Rabbi said that a priest with a blemish within the meaning of Leviticus 21:20 who officiated at services in the Sanctuary was liable to death at the hands of Heaven, but the Sages maintained that he was merely prohibited.[107]

The Mishnah taught that a priest whose hands were deformed should not lift up his hands to say the priestly blessing, and Rabbi Judah said that a priest whose hands were discolored should not lift up his hands, because it would cause the congregation to look at him during this blessing when they should not.[108] A Baraita stated that deformities on the face, hands, or feet were disqualifying for saying the priestly blessing. Rabbi Joshua ben Levi said that a Kohen with spotted hands should not say the blessing. A Baraita taught that one whose hands were curved inwards or bent sideways should not say the blessing. And Rav Huna said that a man whose eyes ran should not say the blessing. But the Gemara noted that such a Kohen in Rav Huna's neighborhood used to say the priestly blessing and apparently even Rav Huna did not object, because the townspeople had become accustomed to the Kohen. And the Gemara cited a Baraita that taught that a man whose eyes ran should not lift up his hands, but he was permitted to do so if the townspeople were accustomed to him. Rabbi Johanan said that a man blind in one eye should not lift up his hands. But the Gemara noted that there was one in Rabbi Johanan's neighborhood who used to lift up his hands, as the townspeople were accustomed to him. And the Gemara cited a Baraita that taught that a man blind in one eye should not lift up his hands, but if the townspeople were accustomed to him, he was permitted. Rabbi Judah said that a man whose hands were discolored should not lift up his hands, but the Gemara cited a Baraita that taught that if most of the men of the town follow the same hand-discoloring occupation, it was permitted.[109]

Rav Ashi deduced from Leviticus 21:20 that arrogance constitutes a blemish.[110]

Leviticus chapter 22[]

The Mishnah reported that when a priest performed the service while unclean in violation of Leviticus 22:3, his brother priests did not charge him before the bet din, but the young priests took him out of the Temple court and split his skull with clubs.[111]

Rav Ashi read the repetitive language of Leviticus 22:9, "And they shall have charge of My charge" — which referred especially to priests and Levites, whom Numbers 18:3–5 repeatedly charged with warnings — to require safeguards to God's commandments.[112]

The Mishnah taught that a vow-offering, as in Leviticus 22:18, was when one said, "It is incumbent upon me to bring a burnt-offering" (without specifying a particular animal). And a freewill-offering was when one said, "This animal shall serve as a burnt-offering" (specifying a particular animal). In the case of vow offerings, one was responsible for replacement of the animal if the animal died or was stolen; but in the case of freewill obligations, one was not held responsible for the animal's replacement if the specified animal died or was stolen.[113]

A Baraita interpreted the words "there shall be no blemish therein" in Leviticus 22:21 to forbid causing a blemish in a sacrificial animal even indirectly.[114]

Ben Zoma interpreted the words "neither shall you do this in your land" in Leviticus 22:24 to forbid castrating even a dog (an animal that one could never offer as a sacrifice).[115]

Interpreting what constitutes profanation of God's Name within the meaning of Leviticus 22:32, Rabbi Johanan said in the name of Rabbi Simeon ben Jehozadak that by a majority vote, it was resolved in the attic of the house of Nitzah in Lydda that if a person is directed to transgress a commandment in order to avoid being killed, the person may transgress any commandment of the Torah to stay alive except idolatry, prohibited sexual relations, and murder. With regard to idolatry, the Gemara asked whether one could commit it to save one's life, as it was taught in a Baraita that Rabbi Ishmael said that if a person is directed to engage in idolatry in order to avoid being killed, the person should do so, and stay alive. Rabbi Ishmael taught that we learn this from Leviticus 18:5, "You shall therefore keep my statutes and my judgments, which if a man do, he shall live in them," which means that a person should not die by them. From this, one might think that a person could openly engage in idolatry in order to avoid being killed, but this is not so, as Leviticus 22:32 teaches, "Neither shall you profane My holy Name; but I will be hallowed". When Rav Dimi came from the Land of Israel to Babylonia, he taught that the rule that one may violate any commandment except idolatry, prohibited sexual relations, and murder to stay alive applied only when there is no royal decree forbidding the practice of Judaism. But Rav Dimi taught that if there is such a decree, one must incur martyrdom rather than transgress even a minor precept. When Ravin came, he said in Rabbi Johanan's name that even absent such a decree, one was allowed to violate a commandment to stay alive only in private; but in public one needed to be martyred rather than violate even a minor precept. Rava bar Rav Isaac said in Rav's name that in this context one should choose martyrdom rather than violate a commandment even to change a shoe strap. Rabbi Jacob said in Rabbi Johanan's name that the minimum number of people for an act to be considered public is ten. And the Gemara taught that ten Jews are required for the event to be public, for Leviticus 22:32 says, "I will be hallowed among the children of Israel".[116]

The Gemara further interpreted what constitutes profanation of God's Name within the meaning of Leviticus 22:32. Rav said that it would profane God's Name if a Torah scholar took meat from a butcher without paying promptly. Abaye said that this would profane God's Name only in a place where vendors did not have a custom of going out to collect payment from their customers. Rabbi Johanan said that it would profane God's Name if a Torah scholar walked six feet without either contemplating Torah or wearing tefillin. Isaac of the School of Rabbi Jannai said that it would profane God's Name if one's bad reputation caused colleagues to become ashamed. Rav Nahman bar Isaac said that an example of this would be where people called on God to forgive so-and-so. Abaye interpreted the words "and you shall love the Lord your God" in Deuteronomy 6:5 to teach that one should strive through one's actions to cause others to love the Name of Heaven. So that if people see that those who study Torah and Mishnah are honest in business and speak pleasantly, then they will accord honor to the Name of God. But if people see that those who study Torah and Mishnah are dishonest in business and discourteous, then they will associate their shortcomings with their being Torah scholars.[117]

Rav Adda bar Abahah taught that a person praying alone does not say the Sanctification (Kedushah) prayer (which includes the words from Isaiah 6:3: Hebrew: קָדוֹשׁ קָדוֹשׁ קָדוֹשׁ יְהוָה צְבָאוֹת; מְלֹא כָל-הָאָרֶץ, כְּבוֹדוֹ, Kadosh, Kadosh, Kadosh, Adonai Tz'vaot melo kol haaretz kevodo, "Holy, Holy, Holy, the Lord of Hosts, the entire world is filled with God's Glory"), because Leviticus 22:32 says: "I will be hallowed among the children of Israel", and thus sanctification requires ten people (a minyan). Rabinai the brother of Rabbi Hiyya bar Abba taught that we derive this by drawing an analogy between the two occurrences of the word "among" (Hebrew: תּוֹךְ, toch) in Leviticus 22:32 ("I will be hallowed among the children of Israel") and in Numbers 16:21, in which God tells Moses and Aaron: "Separate yourselves from among this congregation," referring to Korah and his followers. Just as Numbers 16:21, which refers to a congregation, implies a number of at least ten, so Leviticus 22:32 implies at least ten.[118]

The Tosefta taught that one who robs from a non-Jew must restore what one stole, and the rule applies more strictly when robbing a non-Jew than when robbing a Jew because of the profanation of God's Name (in violation of Leviticus 22:32) involved in robbing a non-Jew.[119]

Leviticus chapter 23[]

Tractate Shabbat in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of the Sabbath in Exodus 16:23 and 29; 20:7–10 (20:8–11 in the NJPS); 23:12; 31:13–17; 35:2–3; Leviticus 19:3; 23:3; Numbers 15:32–36; and Deuteronomy 5:11 (5:12 in the NJPS).[120]

The Mishnah taught that every act that violates the law of the Sabbath also violates the law of a festival, except that one may prepare food on a festival but not on the Sabbath.[121] And the Sifra taught that mention of the Sabbath in Leviticus 23:3 immediately precedes mention of the Festivals in Leviticus 23:4–43 to show that whoever profanes the Festivals is regarded as having profaned the Sabbath, and whoever honors the Festivals is regarded as having honored both the Sabbath and the Festivals.[122]

A Midrash asked to which commandment Deuteronomy 11:22 refers when it says, "For if you shall diligently keep all this commandment that I command you, to do it, to love the Lord your God, to walk in all His ways, and to cleave to Him, then will the Lord drive out all these nations from before you, and you shall dispossess nations greater and mightier than yourselves." Rabbi Levi said that "this commandment" refers to the recitation of the Shema (Deuteronomy 6:4–9), but the Rabbis said that it refers to the Sabbath, which is equal to all the precepts of the Torah.[123]

The Alphabet of Rabbi Akiva taught that when God was giving Israel the Torah, God told them that if they accepted the Torah and observed God's commandments, then God would give them for eternity a most precious thing that God possessed — the World To Come. When Israel asked to see in this world an example of the World To Come, God replied that the Sabbath is an example of the World To Come.[124]

Tractate Beitzah in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws common to all of the Festivals in Exodus 12:3–27, 43–49; 13:6–10; 23:16; 34:18–23; Leviticus 16; 23:4–43; Numbers 9:1–14; 28:16–30:1; and Deuteronomy 16:1–17; 31:10–13.[125]

Tractate Pesachim in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of the Passover (Hebrew: פֶּסַח, Pesach) in Exodus 12:3–27, 43–49; 13:6–10; 23:15; 34:25; Leviticus 23:4–8; Numbers 9:1–14; 28:16–25; and Deuteronomy 16:1–8.[126]

The Gemara noted that in listing the several festivals in Exodus 23:15, Leviticus 23:5, Numbers 28:16, and Deuteronomy 16:1, the Torah always begins with Passover.[127]

Rabbi Akiva (or some say Rabban Johanan ben Zakai) never said in the house of study that it was time to stop studying, except on the eve of Passover and the eve of the Yom Kippur. On the eve of Passover, it was because of the children, so that they might not fall asleep, and on the eve of the Day of Atonement, it was so that they should feed their children before the fast.[128]

The Mishnah taught that a Passover sacrifice was disqualified if it was slaughtered for people who were not qualified to eat it, such as uncircumcised men or people in a state of impurity. But it was fit if it was slaughtered for people who able to eat it and people who were not able to eat it, or for people who were designated for it and people who were not designated for it, or for men circumcised and men uncircumcised, or for people in a state of impurity and people in a state of purity. It was disqualified if it was slaughtered before noon, as Leviticus 23:5 says, "Between the evenings." It was fit if it was slaughtered before the daily offering of the afternoon, but only if someone had been stirring the blood until the blood of the daily offering had been sprinkled. And if that blood had already been sprinkled, the Passover sacrifice was still fit.[129]

The Mishnah noted differences between the first Passover in Exodus 12:3–27, 43–49; 13:6–10; 23:15; 34:25; Leviticus 23:4–8; Numbers 9:1–14; 28:16–25; and Deuteronomy 16:1–8. and the second Passover in Numbers 9:9–13. The Mishnah taught that the prohibitions of Exodus 12:19 that "seven days shall there be no leaven found in your houses" and of Exodus 13:7 that "no leaven shall be seen in all your territory" applied to the first Passover; while at the second Passover, one could have both leavened and unleavened bread in one's house. And the Mishnah taught that for the first Passover, one was required to recite the Hallel (Psalms 113–118) when the Passover lamb was eaten; while the second Passover did not require the reciting of Hallel when the Passover lamb was eaten. But both the first and second Passovers required the reciting of Hallel when the Passover lambs were offered, and both Passover lambs were eaten roasted with unleavened bread and bitter herbs. And both the first and second Passovers took precedence over the Sabbath.[130]

Rabbi Abba distinguished the bull and single ram that Leviticus 9:2 required Aaron to bring for the Inauguration of the Tabernacle from the bull and two rams that Leviticus 23:18 required the High Priest to bring on Shavuot, and thus the Gemara concluded that one cannot reason by analogy from the requirements for the Inauguration to those of Shavuot.[131]

Noting that the discussion of gifts to the poor in Leviticus 23:22 appears between discussions of the festivals — Passover and Shavuot on one side, and Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur on the other — Rabbi Avardimos ben Rabbi Yossi said that this teaches that people who give immature clusters of grapes (as in Leviticus 19:10 and Deuteronomy 24:21), the forgotten sheaf (as in Deuteronomy 24:19), the corner of the field (as in Leviticus 19:9 and 23:22), and the poor tithe (as in Deuteronomy 14:28 and 26:12) is accounted as if the Temple existed and they offered up their sacrifices in it. And for those who do not give to the poor, it is accounted to them as if the Temple existed and they did not offer up their sacrifices in it.[132]

Tractate Peah in the Mishnah, Tosefta, and Jerusalem Talmud interpreted the laws of the harvest of the corner of the field and gleanings to be given to the poor in Leviticus 19:9–10 and 23:22 and Deuteronomy 24:19–21.[133]

The Mishnah taught that the Torah defines no minimum or maximum for the donation of the corners of one's field to the poor.[134] But the Mishnah also taught that one should not make the amount left to the poor less than one-sixtieth of the entire crop. And even though no definite amount is given, the amount given should accord with the size of the field, the number of poor people, and the extent of the yield.[135]

Rabbi Eliezer taught that one who cultivates land in which one can plant a quarter kav of seed is obligated to give a corner to the poor. Rabbi Joshua said land that yields two seah of grain. Rabbi Tarfon said land of at least six handbreadths by six handbreadths. Rabbi Judah ben Betera said land that requires two strokes of a sickle to harvest, and the law is as he spoke. Rabbi Akiva said that one who cultivates land of any size is obligated to give a corner to the poor and the first fruits.[136]

The Mishnah taught that the poor could enter a field to collect three times a day — in the morning, at midday, and in the afternoon. Rabban Gamliel taught that they said this only so that landowners should not reduce the number of times that the poor could enter. Rabbi Akiva taught that they said this only so that landowners should not increase the number of times that the poor had to enter. The landowners of Beit Namer used to harvest along a rope and allowed the poor to collect a corner from every row.[137]

Reading Leviticus 23:22, the Gemara noted that a Baraita (Tosefta Peah 1:5) taught that the optimal way to fulfill the commandment is for the owner to separate the portion for the poor from grain that has not been harvested. If the owner did not separate it from the standing grain, the owner separates it from the sheaves of grain that have been harvested. If the owner did not separate it from the sheaves, the owner separates it from the pile of grain, as long as the owner has not yet smoothed the pile. Once the owner smooths the pile of grain, it becomes obligated in tithes. Therefore, the owner must first tithe the grain and then give a portion of the produce to the poor, so that the poor need not tithe what they receive. The Sages said in the name of Rabbi Ishmael that if the owner did not separate the portion for the poor during any of these stages, and the owner milled the grain and kneaded it into dough, the owner still needed to separate a portion even from the dough and give it to the poor. Even if the owner has harvested the grain, the portion for the poor is still not considered the owner's possession.[138]

The Gemara noted that Leviticus 19:9 includes a superfluous term "by reaping" and reasoned that this must teach that the obligation to leave for the poor applies to crops that the owner uproots as well as to crops that the owner cuts. And the Gemara reasoned that the superfluous words "When you reap" in Leviticus 23:22 teach that the obligation also extends to one who picks a crop by hand.[139]

The Mishnah taught that if a wife foreswore all benefit from other people, her husband could not annul his wife's vow, but she could still benefit from the gleanings, forgotten sheaves, and the corner of the field that Leviticus 19:9–10 and 23:22, and Deuteronomy 24:19–21 commanded farmers to leave for the poor.[140]

Tractate Rosh Hashanah in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of Rosh Hashanah in Leviticus 23:23–25 and Numbers 29:1–6.[141]

The Mishnah taught that Divine judgment is passed on the world at four seasons (based on the world's actions in the preceding year) — at Passover for produce; at Shavuot for fruit; at Rosh Hashanah all creatures pass before God like children of maron (one by one), as Psalm 33:15 says, "He Who fashions the heart of them all, Who considers all their doings." And on Sukkot, judgment is passed in regard to rain.[142]

Rabbi Meir taught that all are judged on Rosh Hashanah and the decree is sealed on Yom Kippur. Rabbi Judah, however, taught that all are judged on Rosh Hashanah and the decree of each and every one of them is sealed in its own time — at Passover for grain, at Shavuot for fruits of the orchard, at Sukkot for water. And the decree of humankind is sealed on Yom Kippur. Rabbi Jose taught that humankind is judged every single day, as Job 7:17–18 says, "What is man, that You should magnify him, and that You should set Your heart upon him, and that You should remember him every morning, and try him every moment?"[143]

Rav Kruspedai said in the name of Rabbi Johanan that on Rosh Hashanah, three books are opened in Heaven — one for the thoroughly wicked, one for the thoroughly righteous, and one for those in between. The thoroughly righteous are immediately inscribed definitively in the book of life. The thoroughly wicked are immediately inscribed definitively in the book of death. And the fate of those in between is suspended from Rosh Hashanah to Yom Kippur. If they deserve well, then they are inscribed in the book of life; if they do not deserve well, then they are inscribed in the book of death. Rabbi Abin said that Psalm 69:29 tells us this when it says, "Let them be blotted out of the book of the living, and not be written with the righteous." "Let them be blotted out from the book" refers to the book of the wicked. "Of the living" refers to the book of the righteous. "And not be written with the righteous" refers to the book of those in between. Rav Nahman bar Isaac derived this from Exodus 32:32, where Moses told God, "if not, blot me, I pray, out of Your book that You have written." "Blot me, I pray" refers to the book of the wicked. "Out of Your book" refers to the book of the righteous. "That you have written" refers to the book of those in between. It was taught in a Baraita that the House of Shammai said that there will be three groups at the Day of Judgment — one of thoroughly righteous, one of thoroughly wicked, and one of those in between. The thoroughly righteous will immediately be inscribed definitively as entitled to everlasting life; the thoroughly wicked will immediately be inscribed definitively as doomed to Gehinnom, as Daniel 12:2 says, "And many of them who sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life and some to reproaches and everlasting abhorrence." Those in between will go down to Gehinnom and scream and rise again, as Zechariah 13:9 says, "And I will bring the third part through the fire, and will refine them as silver is refined, and will try them as gold is tried. They shall call on My name and I will answer them." Of them, Hannah said in 1 Samuel 2:6, "The Lord kills and makes alive, He brings down to the grave and brings up." The House of Hillel, however, taught that God inclines the scales towards grace (so that those in between do not have to descend to Gehinnom), and of them David said in Psalm 116:1–3, "I love that the Lord should hear my voice and my supplication . . . The cords of death compassed me, and the straits of the netherworld got hold upon me," and on their behalf David composed the conclusion of Psalm 116:6, "I was brought low and He saved me."[144]

The Jerusalem Talmud reported that Jews wear white on the High Holy Days. Rabbi Hama the son of Rabbi Hanina and Rabbi Hoshaiah disagreed about how to interpret Deuteronomy 4:8, "And what great nation is there, that has statutes and ordinances so righteous as all this law." One said: "And what great nation is there?" Ordinarily those who know they are on trial wear black, wrap themselves in black, and let their beards grow, since they do not know how their trial will turn out. But that is not how it is with Israel. Rather, on the day of their trial, on Rosh Hashanah, they wear white, wrap themselves in white, and shave their beards and eat, drink, and rejoice, for they know that God does miracles for them. The other said: "And what great nation is there?" Ordinarily, if the ruler directs that the trial is on a certain day, and the robber says that the trial is on the next day, they listen to the ruler. But that is not how it is with God. The earthly court says that Rosh Hashanah falls on a certain day, and God directs the ministering angels to set up the platform, let the defenders rise, and let the prosecutors rise, for God's children have announced, that it is Rosh Hashanah. If the court determined that the month of Elul spanned a full 30 days, so that Rosh Hashanah would fall on the next day, then God would direct the ministering angels to remove the platform, remove the defense attorneys, remove the prosecutors, for God's children had declared Elul a full month. For Psalm 81:5 says of Rosh Hashanah, "For it is a statute for Israel, an ordinance of the God of Jacob," and thus if it is not a statute for Israel, then it also is not an ordinance of God.[145]

A Baraita taught that on Rosh Hashanah, God remembered each of Sarah, Rachel, and Hannah and decreed that they would bear children. Rabbi Eliezer found support for the Baraita from the parallel use of the word "remember" in Genesis 30:22, which says about Rachel, "And God remembered Rachel," and in Leviticus 23:24, which calls Rosh Hashanah "a remembrance of the blast of the trumpet."[146]

Rabbi Abbahu taught that Jews sound a blast with a shofar made from a ram's horn on Rosh Hashanah, because God instructed them to do so to bring before God the memory of the binding of Isaac, in whose stead Abraham sacrificed a ram, and thus God will ascribe it to worshipers as if they had bound themselves before God. Rabbi Isaac asked why one sounds (Hebrew: תוקעין, tokin) a blast on Rosh Hashanah, and the Gemara answered that God states in Psalm 81:4: "Sound (Hebrew: תִּקְעוּ, tiku) a shofar."[147]

Rabbi Joshua son of Korchah taught that Moses stayed on Mount Sinai 40 days and 40 nights, reading the Written Law by day, and studying the Oral Law by night. After those 40 days, on the 17th of Tammuz, Moses took the Tablets of the Law, descended into the camp, broke the Tablets in pieces, and killed the Israelite sinners. Moses then spent 40 days in the camp, until he had burned the Golden Calf, ground it into powder like the dust of the earth, destroyed the idol worship from among the Israelites, and put every tribe in its place. And on the New Moon (Hebrew: ראש חודש, Rosh Chodesh) of Elul (the month before Rosh Hashanah), God told Moses in Exodus 24:12: "Come up to Me on the mount," and let them sound the shofar throughout the camp, for, behold, Moses has ascended the mount, so that they do not go astray again after the worship of idols. God was exalted with that shofar, as Psalm 47:5 says, "God is exalted with a shout, the Lord with the sound of a trumpet." Therefore, the Sages instituted that the shofar should be sounded on the New Moon of Elul every year.[148]

Tractate Yoma in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of Yom Kippur in Leviticus 16 and 23:26–32 and Numbers 29:7–11.[149]

Rabbi Yannai taught that from the very beginning of the world's creation, God foresaw the deeds of the righteous and the wicked, and provided Yom Kippur in response. Rabbi Yannai taught that Genesis 1:2, "And the earth was desolate," alludes to the deeds of the wicked; Genesis 1:3, "And God said: 'Let there be light,'" to those of the righteous; Genesis 1:4, "And God saw the light, that it was good," to the deeds of the righteous; Genesis 1:4, "And God made a division between the light and the darkness": between the deeds of the righteous and those of the wicked; Genesis 1:5, "And God called the light day," alludes to the deeds of the righteous; Genesis 1:5, "And the darkness called He night," to those of the wicked; Genesis 1:5, "and there was evening," to the deeds of the wicked; Genesis 1:5, "and there was morning," to those of the righteous. And Genesis 1:5, "one day," teaches that God gave the righteous one day — Yom Kippur.[150]

Similarly, Rabbi Judah bar Simon interpreted Genesis 1:5, "And God called the light day," to symbolize Jacob/Israel; "and the darkness he called night," to symbolize Esau; "and there was evening," to symbolize Esau; "and there was morning," to symbolize Jacob. And "one day" teaches that God gave Israel one unique day over which darkness has no influence — the Day of Atonement.[151]

Rabbi Akiva taught that because Leviticus 23:27 says, "the tenth day of this seventh month is the Day of Atonement," and Leviticus 23:32 says, "It shall be to you a Sabbath," whenever Yom Kippur coincides with a Sabbath, whoever unwittingly performs work is liable for violating both Yom Kippur and the Sabbath. But Rabbi Ishmael said that such a person is liable on only a single count.[152]

Chapter 8 of tractate Yoma in the Mishnah and Babylonian Talmud and chapter 4 of tractate Kippurim (Yoma) in the Tosefta interpreted the laws of self-denial in Leviticus 16:29–34 and 23:26–32.[153] The Mishnah taught that on Yom Kippur, one must not eat, drink, wash, anoint oneself, put on sandals, or have sexual intercourse. Rabbi Eliezer (whom the halachah follows) taught that a king or bride may wash the face, and a woman after childbirth may put on sandals. But the sages forbad doing so.[154] The Tosefta taught that one must not put on even felt shoes. But the Tosefta taught that minors can do all these things except put on sandals, for appearance's sake.[155] The Mishnah held a person culpable to punishment for eating an amount of food equal to a large date (with its pit included), or for drinking a mouthful of liquid. For the purpose of calculating the amount consumed, one combines all amounts of food together, and all amounts liquids together, but not amounts of foods together with amounts of liquids.[156] The Mishnah obliged one who unknowingly or forgetfully ate and drank to bring only one sin-offering. But one who unknowingly or forgetfully ate and performed labor had to bring two sin-offerings. The Mishnah did not hold one culpable who ate foods unfit to eat, or drank liquids unfit to drink (like fish-brine).[157] The Mishnah taught that one should not afflict children at all on Yom Kippur. In the two years before they become Bar or Bat Mitzvah, one should train children to become used to religious observances (for example by fasting for several hours).[158] The Mishnah taught that one should give food to a pregnant woman who smelled food and requested it. One should feed to a sick person at the direction of experts, and if no experts are present, one feeds a sick person who requests food.[159] The Mishnah taught that one may even give unclean food to one seized by a ravenous hunger, until the person's eyes are opened. Rabbi Matthia ben Heresh said that one who has a sore throat may drink medicine even on the Sabbath, because it presented the possibility of danger to human life, and every danger to human life suspends the laws of the Sabbath.[160]

The Gemara taught that in conducting the self-denial required in Leviticus 16:29–34 and 23:26–32, one adds a little time from the surrounding ordinary weekdays to the holy day. Rabbi Ishmael derived this rule from what had been taught in a Baraita: One might read Leviticus 23:32, "And you shall afflict your souls on the ninth day," literally to mean that one begins fasting the entire day on the ninth day of the month; Leviticus 23:32 therefore says, "in the evening." One might read "in the evening" to mean "after dark" (which the Hebrew calendar would reckon as part of the tenth day); Leviticus 23:32 therefore says, "in the ninth day." The Gemara thus concluded that one begins fasting while it is still day on the ninth day, adding some time from the profane day (the ninth) to the holy day (the tenth). The Gemara read the words, "from evening to evening," in Leviticus 23:32 to teach that one adds some time to Yom Kippur from both the evening before and the evening after. Because Leviticus 23:32 says, "You shall rest," the Gemara applied the rule to Sabbaths as well. Because Leviticus 23:32 says "your Sabbath" (your day of rest), the Gemara applied the rule to other Festivals (in addition to Yom Kippur); wherever the law creates an obligation to rest, we add time to that obligation from the surrounding profane days to the holy day. Rabbi Akiva, however, read Leviticus 23:32, "And you shall afflict your souls on the ninth day," to teach the lesson learned by Rav Hiyya bar Rav from Difti (that is, Dibtha, below the Tigris, southeast of Babylon). Rav Hiyya bar Rav from Difti taught in a Baraita that Leviticus 23:32 says "the ninth day" to indicate that if people eat and drink on the ninth day, then Scripture credits it to them as if they fasted on both the ninth and the tenth days (because Leviticus 23:32 calls the eating and drinking on the ninth day "fasting").[161]

The Mishnah taught that the High Priest said a short prayer in the outer area.[162] The Jerusalem Talmud taught that this was the prayer of the High Priest on the Day of Atonement, when he left the Holy Place whole and in one piece: "May it be pleasing before you, Lord, our God of our fathers, that a decree of exile not be issued against us, not this day or this year, but if a decree of exile should be issued against us, then let it be exile to a place of Torah. May it be pleasing before you, Lord, our God and God of our fathers, that a decree of want not be issued against us, not this day or this year, but if a decree of want should be issued against us, then let it be a want because of the performance of religious duties. May it be pleasing before you, Lord, our God and God of our fathers, that this year be a year of cheap food, full bellies, good business; a year in which the earth forms clods, then is parched so as to form scabs, and then moistened with dew, so that your people, Israel, will not be in need of the help of one another. And do not heed the prayer of travelers that it not rain." The Rabbis of Caesarea added, "And concerning your people, Israel, that they not exercise dominion over one another." And for the people who live in the Sharon plain he would say this prayer, "May it be pleasing before you, Lord, our God and God of our fathers, that our houses not turn into our graves."[163]

Reading Song of Songs 6:11, Rabbi Joshua ben Levi compared Israel to a nut-tree. Rabbi Azariah taught that just as when a nut falls into the dirt, you can wash it, restore it to its former condition, and make it fit for eating, so however much Israel may be defiled with iniquities all the rest of the year, when the Day of Atonement comes, it makes atonement for them, as Leviticus 16:30 says, "For on this day shall atonement be made for you, to cleanse you."[164]

Resh Lakish taught that great is repentance, for because of it, Heaven accounts premeditated sins as errors, as Hosea 14:2 says, "Return, O Israel, to the Lord, your God, for you have stumbled in your iniquity." "Iniquity" refers to premeditated sins, and yet Hosea calls them "stumbling," implying that Heaven considers those who repent of intentional sins as if they acted accidentally. But the Gemara said that that is not all, for Resh Lakish also said that repentance is so great that with it, Heaven accounts premeditated sins as though they were merits, as Ezekiel 33:19 says, "And when the wicked turns from his wickedness, and does that which is lawful and right, he shall live thereby." The Gemara reconciled the two positions, clarifying that in the sight of Heaven, repentance derived from love transforms intentional sins to merits, while repentance out of fear transforms intentional sins to unwitting transgressions.[165]

The Jerusalem Talmud taught that the evil impulse (Hebrew: יצר הרע, yetzer hara) craves only what is forbidden. The Jerusalem Talmud illustrated this by relating that on the Day of Atonement, Rabbi Mana went to visit Rabbi Haggai, who was feeling weak. Rabbi Haggai told Rabbi Mana that he was thirsty. Rabbi Mana told Rabbi Haggai to go drink something. Rabbi Mana left and after a while came back. Rabbi Mana asked Rabbi Haggai what happened to his thirst. Rabbi Haggai replied that when Rabbi Mana told him that he could drink, his thirst went away.[166]

Rav Mana of Sha'ab (in Galilee) and Rav Joshua of Siknin in the name of Rav Levi compared repentance at the High Holidays to the case of a province that owed arrears on its taxes to the king, and the king came to collect the debt. When the king was within ten miles, the nobility of the province came out and praised him, so he freed the province of a third of its debt. When he was within five miles, the middle-class people of the province came out and praised him, so he freed the province of another third of its debt. When he entered the province, all the people of the province — men, women, and children — came out and praised him, so he freed them of all of their debt. The king told them to let bygones be bygones; from then on they would start a new account. In a similar manner, on the eve of Rosh Hashanah, the leaders of the generation fast, and God absolves them of a third of their iniquities. From Rosh Hashanah to Yom Kippur, private individuals fast, and God absolves them of a third of their iniquities. On Yom Kippur, everyone fasts — men, women and children — and God tells Israel to let bygones be bygones; from then onwards we begin a new account. From Yom Kippur to Sukkot, all Israel are busy with the performance of religious duties. One is busy with a sukkah, one with a lulav. On the first day of Sukkot, all Israel stand in the presence of God with their palm-branches and etrogs in honor of God's name, and God tells them to let bygones be bygones; from now we begin a new account. Thus in Leviticus 23:40, Moses exhorts Israel: "You shall take on the first day [of Sukkot] the fruit of goodly trees, branches of palm trees and the boughs of thick trees, and willows of the brook; and you shall rejoice before the Lord your God." Rabbi Aha explained that the words, "For with You there is forgiveness," in Psalm 130:4signify that forgiveness waits with God from Rosh Hashanah onward. And forgiveness waits that long so (in the words of Psalm 130:4) "that You may be feared" and God may impose God's awe upon God's creatures (through the suspense and uncertainty).[167]

Tractate Sukkah in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of Sukkot in Exodus 23:16; 34:22; Leviticus 23:33–43; Numbers 29:12–34; and Deuteronomy 16:13–17; 31:10–13.[168]

The Mishnah taught that a sukkah can be no more than 20 cubits high. Rabbi Judah, however, declared taller sukkot valid. The Mishnah taught that a sukkah must be at least 10 handbreadths high, have three walls, and have more shade than sun.[169] The House of Shammai declared invalid a sukkah made 30 days or more before the festival, but the House of Hillel pronounced it valid. The Mishnah taught that if one made the sukkah for the purpose of the festival, even at the beginning of the year, it is valid.[170]

The Mishnah taught that a sukkah under a tree is as invalid as a sukkah within a house. If one sukkah is erected above another, the upper one is valid, but the lower is invalid. Rabbi Judah said that if there are no occupants in the upper one, then the lower one is valid.[171]

It invalidates a sukkah to spread a sheet over the sukkah because of the sun, or beneath it because of falling leaves, or over the frame of a four-post bed. One may spread a sheet, however, over the frame of a two-post bed.[172]

It is not valid to train a vine, gourd, or ivy to cover a sukkah and then cover it with sukkah covering (s'chach). If, however, the sukkah-covering exceeds the vine, gourd, or ivy in quantity, or if the vine, gourd, or ivy is detached, it is valid. The general rule is that one may not use for sukkah-covering anything that is susceptible to ritual impurity (tumah) or that does not grow from the soil. But one may use for sukkah-covering anything not susceptible to ritual impurity that grows from the soil.[173]

Bundles of straw, wood, or brushwood may not serve as sukkah-covering. But any of them, if they are untied, are valid. All materials are valid for the walls.[174]

Rabbi Judah taught that one may use planks for the sukkah-covering, but Rabbi Meir taught that one may not. The Mishnah taught that it is valid to place a plank four handbreadths wide over the sukkah, provided that one does not sleep under it.[175]

The Mishnah taught that a stolen or a withered palm-branch is invalid to fulfill the commandment of Leviticus 23:40. If its top is broken off or its leaves detached from the stem, it is invalid. If its leaves are merely spread apart but still joined to the stem at their roots, it is valid. Rabbi Judah taught that in that case, one should tie the leaves at the top. A palm-branch that is three handbreadths in length, long enough to wave, is valid.[176] The Gemara explained that a withered palm branch fails to meets the requirement of Leviticus 23:40 because it is not (in the term of Leviticus 23:40) "goodly." Rabbi Johanan taught in the name of Rabbi Simeon ben Yohai that a stolen palm-branch is unfit because use of it would be a precept fulfilled through a transgression, which is forbidden. Rabbi Ammi also stated that a withered palm-branch is invalid because it is not in the word of Leviticus 23:40 "goodly," and a stolen one is invalid because it constitutes a precept fulfilled through a transgression.[177]

Similarly, the Mishnah taught that a stolen or withered myrtle is not valid. If its tip is broken off, or its leaves are severed, or its berries are more numerous than its leaves, it is invalid. But if one picks off berries to diminish their number, it is valid. One may not, however, pick them on the Festival.[178]

Similarly, the Mishnah taught that a stolen or withered willow-branch is invalid. One whose tip is broken off or whose leaves are severed is invalid. One that has shriveled or lost some of its leaves, or one grown in a naturally watered soil, is valid.[179]