Acharei Mot

Acharei Mot (also Aharei Mot, Aharei Moth, or Acharei Mos) (אַחֲרֵי מוֹת, Hebrew for "after the death") is the 29th weekly Torah portion in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading. It is the sixth weekly portion (פָּרָשָׁה, parashah) in the Book of Leviticus, containing Leviticus 16:1–18:30. It is named after the fifth and sixth Hebrew words of the parashah, its first distinctive words.

The parashah sets forth the law of the Yom Kippur ritual, centralized offerings, blood, and sexual practices. The parashah is made up of 4,294 Hebrew letters, 1,170 Hebrew words, 80 verses, and 154 lines in a Torah Scroll (סֵפֶר תּוֹרָה, Sefer Torah).[1]

Jews generally read it in April or early May. The lunisolar Hebrew calendar contains up to 55 weeks, the exact number varying between 50 in common years and 54 or 55 in leap years. In leap years (for example, 2022, 2024, and 2027), parashah Acharei Mot is read separately on the 29th Sabbath after Simchat Torah. In common years (for example, 2021, 2023, 2025, 2026, and 2028), parashah Acharei Mot is combined with the next parashah, Kedoshim, to help achieve the needed number of weekly readings.[2]

Traditional Jews also read parts of the parashah as Torah readings for Yom Kippur. Leviticus 16, which addresses the Yom Kippur ritual, is the traditional Torah reading for the Yom Kippur morning (Shacharit) service, and Leviticus 18 is the traditional Torah reading for the Yom Kippur afternoon (Minchah) service. Some Conservative congregations substitute readings from Leviticus 19 for the traditional Leviticus 18 in the Yom Kippur afternoon Minchah service.[3] And in the standard Reform High Holidays prayerbook (machzor), Deuteronomy 29:9–14 and 30:11–20 are the Torah readings for the morning Yom Kippur service, in lieu of the traditional Leviticus 16.[4]

Readings[]

In traditional Sabbath Torah reading, the parashah is divided into seven readings, or עליות, aliyot.[5]

First reading — Leviticus 16:1–17[]

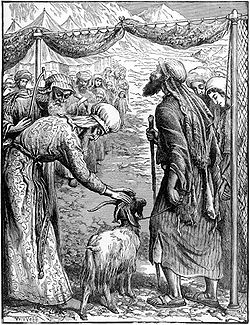

The first reading begins the ritual of Yom Kippur. After the death of Aaron's sons, God told Moses to tell Aaron not to come at will into the Most Holy Place (קֹדֶשׁ הַקֳּדָשִׁים, Kodesh Ha-Kodashim), lest he die, for God appeared in the cloud there.[6] Aaron was to enter only after bathing in water, dressing in his sacral linen tunic, breeches, sash, and turban, and bringing a bull for a sin offering, two rams for burnt offerings, and two he-goats for sin offerings.[7] Aaron was to take the two goats to the entrance of the Tabernacle and place lots upon them, one marked for the Lord and the other for Azazel.[8] Aaron was to offer the goat designated for the Lord as a sin offering, and to send off to the wilderness the goat designated for Azazel.[9] Aaron was then to offer the bull of sin offering.[10] Aaron was then to take a pan of glowing coals from the altar and two handfuls of incense and put the incense on the fire before the Most Holy Place, so that the cloud from the incense would screen the Ark of the Covenant.[11] He was to sprinkle some of the bull's blood and then some of the goat's blood over and in front of the Ark, to purge the Shrine of the uncleanness and transgression of the Israelites.[12]

Second reading — Leviticus 16:18–24[]

In the second reading (עליה, aliyah), Aaron was then to apply some of the bull's blood and goat's blood to the altar, to cleanse and consecrate it.[13] Aaron was then to lay his hands on the head of the live goat, confess over it the Israelites' sins, putting them on the head of the goat, and then through a designated man send it off to the wilderness to carry their sins to an inaccessible region.[14] Then Aaron was to go into the Tabernacle, take off his linen vestments, bathe in water, put on his vestments, and then offer the burnt offerings.[15]

Third reading — Leviticus 16:25–34[]

In the third reading (עליה, aliyah), Aaron was to offer the fat of the sin-offering.[16] The person who set the Azazel-goat (sometimes referred to in English as a scapegoat) free was to wash his clothes and bathe in water.[17] The bull and goat of sin offering were to be taken outside the camp and burned, and he who burned them was to wash his clothes and bathe in water.[18] The text then commands this law for all time: On the tenth day of the seventh month, Jews and aliens who reside with them were to practice self-denial and do no work.[19] On that day, the High Priest was to put on the linen vestments, purge the Tabernacle, and make atonement for the Israelites once a year.[20]

Fourth reading — Leviticus 17:1–7[]

The fourth reading (עליה, aliyah) begins what scholars call the Holiness Code. God prohibited Israelites from slaughtering oxen, sheep, or goats meant for sacrifice without bringing them to the Tabernacle as an offering.[21]

Fifth reading — Leviticus 17:8–18:5[]

In the fifth reading (עליה, aliyah), God threatened excision (כרת, karet) for Israelites who slaughtered oxen, sheep, or goats meant for sacrifice without bringing them to the Tabernacle as an offering.[22] God prohibited consuming blood.[23] One who hunted an animal for food was to pour out its blood and cover it with earth.[24] Anyone who ate what had died or had been torn by beasts was to wash his clothes, bathe in water, and remain unclean until evening.[25] God told the Israelites not to follow the practices of the Egyptians or the Canaanites, but to follow God's laws.[26]

Sixth reading — Leviticus 18:6–21[]

In the sixth reading (עליה, aliyah), God prohibited any Israelite from uncovering the nakedness of his father, mother, father's wife, sister, grandchild, half-sister, aunt, daughter-in-law, or sister-in-law.[27] A man could not marry a woman and her daughter, a woman and her granddaughter, or a woman and her sister during the other's lifetime.[28] A man could not cohabit with a woman during her period or with his neighbor's wife.[29] Israelites were not to allow their children to be offered up to Molech.[30]

Seventh reading — Leviticus 18:22–30[]

In the seventh reading (עליה, aliyah), God prohibited a man from lying with a young boy as with a woman.[31] God prohibited bestiality.[32] God explained that the Canaanites defiled themselves by adopting these practices, and any who did any of these things would be cut off from their people.[33]

In ancient parallels[]

The parashah has parallels in these ancient sources:

Leviticus chapter 16[]

Two of the Ebla tablets written between about 2500 and 2250 BCE in what is now Syria describe rituals to prepare a woman to marry the king of Ebla, one of which parallels those of the scapegoat in Leviticus 16:7–22. The tablets describe that to prepare for her wedding to the king, the woman hung the necklace of her old life around the neck of a goat and drove it into the hills of Alini, "Where it may stay forever."[34]

In inner-biblical interpretation[]

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these Biblical sources:[35]

Leviticus chapter 16[]

Yom Kippur[]

Leviticus 16:1–34 refers to the Festival of Yom Kippur. In the Hebrew Bible, Yom Kippur is called:

- the Day of Atonement (יוֹם הַכִּפֻּרִים, Yom HaKippurim)[36] or a Day of Atonement (יוֹם כִּפֻּרִים, Yom Kippurim);[37]

- a Sabbath of solemn rest (שַׁבַּת שַׁבָּתוֹן, Shabbat Shabbaton);[38] and

- a holy convocation (מִקְרָא-קֹדֶשׁ, mikrah kodesh).[39]

Much as Yom Kippur, on the 10th of the month of Tishrei, precedes the Festival of Sukkot, on the 15th of the month of Tishrei, Exodus 12:3–6 speaks of a period starting on the 10th of the month of Nisan preparatory to the Festival of Passover, on the 15th of the month of Nisan.

Leviticus 16:29–34 and 23:26–32 and Numbers 29:7–11 present similar injunctions to observe Yom Kippur. Leviticus 16:29 and 23:27 and Numbers 29:7 set the Holy Day on the tenth day of the seventh month (Tishrei). Leviticus 16:29 and 23:27 and Numbers 29:7 instruct that "you shall afflict your souls." Leviticus 23:32 makes clear that a full day is intended: "you shall afflict your souls; in the ninth day of the month at evening, from evening to evening." And Leviticus 23:29 threatens that whoever "shall not be afflicted in that same day, he shall be cut off from his people." Leviticus 16:29 and Leviticus 23:28 and Numbers 29:7 command that you "shall do no manner of work." Similarly, Leviticus 16:31 and 23:32 call it a "Sabbath of solemn rest." And in 23:30, God threatens that whoever "does any manner of work in that same day, that soul will I destroy from among his people." Leviticus 16:30, 16:32–34, and 23:27–28, and Numbers 29:11 describe the purpose of the day to make atonement for the people. Similarly, Leviticus 16:30 speaks of the purpose "to cleanse you from all your sins," and Leviticus 16:33 speaks of making atonement for the most holy place, the tent of meeting, the altar; and the priests. Leviticus 16:29 instructs that the commandment applies both to "the home-born" and to "the stranger who sojourns among you." Leviticus 16:3–25 and 23:27 and Numbers 29:8–11 command offerings to God. And Leviticus 16:31 and 23:31 institute the observance as "a statute forever."

Leviticus 16:3–28 sets out detailed procedures for the priest's atonement ritual during the time of the Temple.

To make atonement (כָּפַר, kapar) is a major theme of Leviticus 16, appearing 15 times in the chapter.[40] Leviticus 16:6, 16, and 30–34 each summarize this purpose of Yom Kippur. Similarly, Exodus 30:10 foreshadows this purpose in the description of the altar, and Leviticus 23:27–28 echoes that purpose in its listing of the Festivals.

In Leviticus 16:8–10, chance determined which goat was to be offered and which goat was to be sent into the wilderness. Proverbs 16:33 teaches that when lots are cast, God determines the result.

Leviticus 25:8–10 instructs that after seven Sabbatical years, on the Jubilee year, on the day of atonement, the Israelites were to proclaim liberty throughout the land with the blast of the horn and return every man to his possession and to his family.

In Isaiah 57:14–58:14, the Haftarah for Yom Kippur morning, God describes "the fast that I have chosen [on] the day for a man to afflict his soul." Isaiah 58:3–5 make clear that "to afflict the soul" was understood as fasting. But Isaiah 58:6–10 goes on to impress that "to afflict the soul," God also seeks acts of social justice: "to loose the fetters of wickedness, to undo the bands of the yoke," "to let the oppressed go free," "to give your bread to the hungry, and . . . bring the poor that are cast out to your house," and "when you see the naked, that you cover him."

Leviticus chapter 17[]

Deuteronomy 12:1–28, like Leviticus 17:1–10, addresses the centralization of sacrifices and the permissibility of eating meat. While Leviticus 17:3–4 prohibited killing an ox, lamb, or goat (each a sacrificial animal) without bringing it to the door of the Tabernacle as an offering to God, Deuteronomy 12:15 allows killing and eating meat in any place.

While Leviticus 17:10 announced that God would set God’s Face against those who consume blood, in Amos 9:4, the 8th century BCE prophet Amos announced a similar judgment that God would set God’s Eyes for evil upon those who take advantage of the poor.

In early nonrabbinic interpretation[]

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these early nonrabbinic sources:[41]

Leviticus chapter 16[]

The book of Jubilees taught that it was ordained that the children of Israel should afflict themselves on the tenth day of the seventh month because that was the day that the news came to Jacob that made him weep for the loss of his son Joseph. His descendants thus made atonement for themselves with a young goat, for Joseph's brothers had slaughtered a kid and dipped the coat of Joseph in the blood, and sent it to Jacob on that day.[42]

Philo taught that Moses proclaimed the fast of Yom Kippur a feast and named it the greatest of feasts, "a Sabbath of Sabbaths," for many reasons. First is temperance, for when people have learned how to be indifferent to food and drink, they can easily disregard superfluous things. Second is that everyone thereby devotes their entire time to nothing else but prayers and supplications. And third is that the fast occurs at the conclusion of harvest time, to teach people not to rely solely on the food that they have accumulated as the cause of health or life, but on God, Who rules in the world and Who nourished our ancestors in the desert for 40 years.[43]

Leviticus chapter 17[]

Professor Isaiah Gafni of Hebrew University of Jerusalem noted that in the Book of Tobit, the protagonist Tobit observed the dietary laws.[44]

Leviticus chapter 18[]

The Damascus Document of the Qumran sectarians prohited a man’s marrying his niece, deducing this from the prohibition in Leviticus 18:13 of a woman’s marrying her nephew. Professor Lawrence Schiffman of New York University noted that this was a point of contention between the Pharisees and other Jewish groups in Second Temple times.[45]

In classical rabbinic interpretation[]

The parashah is discussed in these rabbinic sources from the era of the Mishnah and the Talmud:[46]

Leviticus chapter 16[]

Rabbi Levi taught that God gave Leviticus 16:1–34 on the day that the Israelites set up the Tabernacle. Rabbi Johanan said in the name of Rabbi Bana'ah that the Torah was transmitted in separate scrolls, as Psalm 40:8 says, "Then said I, 'Lo I am come, in the roll of the book it is written of me.'" Rabbi Simeon ben Lakish (Resh Lakish), however, said that the Torah was transmitted in its entirety, as Deuteronomy 31:26, "Take this book of the law." The Gemara reported that Rabbi Johanan interpreted Deuteronomy 31:26, "Take this book of the law," to refer to the time after the Torah had been joined together from its several parts. And the Gemara suggested that Resh Lakish interpreted Psalm 40:8, "in a roll of the book written of me," to indicate that the whole Torah is called a "roll," as Zechariah 5:2 says, "And he said to me, 'What do you see?' And I answered, 'I see a flying roll.'" Or perhaps, the Gemara suggested, it is called "roll" for the reason given by Rabbi Levi, who said that God gave eight sections of the Torah, which Moses then wrote on separate rolls, on the day on which the Tabernacle was set up. They were: the section of the priests in Leviticus 21, the section of the Levites in Numbers 8:5–26 (as the Levites were required for the service of song on that day), the section of the unclean (who would be required to keep the Passover in the second month) in Numbers 9:1–14, the section of the sending of the unclean out of the camp (which also had to take place before the Tabernacle was set up) in Numbers 5:1–4, the section of Leviticus 16:1–34 (dealing with Yom Kippur, which Leviticus 16:1 states was transmitted immediately after the death of Aaron's two sons), the section dealing with the drinking of wine by priests in Leviticus 10:8–11, the section of the lights of the menorah in Numbers 8:1–4, and the section of the red heifer in Numbers 19 (which came into force as soon as the Tabernacle was set up).[47]

Rabbi Yannai taught that from the very beginning of the world’s creation, God foresaw the deeds of the righteous and the wicked, and provided Yom Kippur in response. Rabbi Yannai taught that Genesis 1:2, “And the earth was desolate,” alludes to the deeds of the wicked; Genesis 1:3, “And God said: ‘Let there be light,’” to those of the righteous; Genesis 1:4, “And God saw the light, that it was good,” to the deeds of the righteous; Genesis 1:4, “And God made a division between the light and the darkness”: between the deeds of the righteous and those of the wicked; Genesis 1:5, “And God called the light day,” alludes to the deeds of the righteous; Genesis 1:5, “And the darkness called He night,” to those of the wicked; Genesis 1:5, “and there was evening,” to the deeds of the wicked; Genesis 1:5, “and there was morning,” to those of the righteous. And Genesis 1:5, “one day,” teaches that God gave the righteous one day — Yom Kippur.[48]

Similarly, Rabbi Judah bar Simon interpreted Genesis 1:5, “And God called the light day,” to symbolize Jacob/Israel; “and the darkness he called night,” to symbolize Esau; “and there was evening,” to symbolize Esau; “and there was morning,” to symbolize Jacob. And “one day” teaches that God gave Israel one unique day over which darkness has no influence — the Day of Atonement.[49]

Rabbi Hiyya bar Abba taught that Aaron's sons died on the first of Nisan, but Leviticus 16:1 mentions their death in connection with the Day of Atonement. Rabbi Hiyya explained that this teaches that as the Day of Atonement effects atonement, so the death of the righteous effects atonement. We know that the Day of Atonement effects atonement from Leviticus 16:30, which says, "For on this day shall atonement be made for you, to cleanse you." And we learn that the death of the righteous effects atonement from 2 Samuel 21:14, which says, "And they buried the bones of Saul and Jonathan his son," and then says, "After that God was entreated for the land."[50]

A Midrash noted that Scripture records the death of Nadab and Abihu in numerous places (Leviticus 10:2 and 16:1; Numbers 3:4 and 26:61; and 1 Chronicles 24:2). This teaches that God grieved for Nadab and Abihu, for they were dear to God. And thus Leviticus 10:3 quotes God to say: "Through them who are near to Me I will be sanctified."[51]

Reading the words of Leviticus 16:1, "the death of the two sons of Aaron, when they drew near before the Lord, and died," Rabbi Jose deduced that Aaron's sons died because they drew near to enter the Holy of Holies.[52]

The Rabbis told in a Baraita an account in relation to Leviticus 16:2. Once a Sadducee High Priest arranged the incense outside and then brought it inside the Holy of Holies. As he left the Holy, he was very glad. His father met him and told him that although they were Sadducees, they were afraid of the Pharisees. He replied that all his life he was aggrieved because of the words of Leviticus 16:2, "For I appear in the cloud upon the Ark-cover." (The Sadducees interpreted Leviticus 16:2 as if it said: "Let him not come into the holy place except with the cloud of incense, for only thus, with the cloud, am I to be seen on the Ark-cover.") The Sadducee wondered when the opportunity would come for him to fulfill the verse. He asked how, when such an opportunity came to his hand, he could not have fulfilled it. The Baraita reported that only a few days later he died and was thrown on the dung heap and worms came forth from his nose. Some say he was smitten as he came out of the Holy of Holies. For Rabbi Hiyya taught that a noise was heard in the Temple Court, for an angel struck him down on his face. The priests found a mark like a calf's hoof on his shoulder, evincing, as Ezekiel 1:7 reports of angels, "And their feet were straight feet, and the sole of their feet was like the sole of a calf's foot."[53]

Tractate Yoma in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of Yom Kippur in Leviticus 16 and 23:26–32 and Numbers 29:7–11.[54]

Tractate Beitzah in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws common to all of the Festivals in Exodus 12:3–27, 43–49; 13:6–10; 23:16; 34:18–23; Leviticus 16; 23:4–43; Numbers 9:1–14; 28:16–30:1; and Deuteronomy 16:1–17; 31:10–13.[55]

The Mishnah taught that during the days of the Temple, seven days before Yom Kippur, they would move the High Priest from his house to the cell of the counselors and prepare another priest to take his place in case anything impure happened to him to make him unfit to perform the service. Rabbi Judah said that they prepared another wife for him, in case his wife should die, as Leviticus 16:6 says that "he shall make atonement for himself and for his house" and "his house" means "his wife." But they told Rabbi Judah that if they would do so, then there would be no end to the matter, as they would have to prepare a third wife in case the second died, and so on.[56] The rest of the year, the High Priest would offer sacrifices only if he wanted to, but during the seven days before Yom Kippur, he would sprinkle the blood of the sacrifices, burn the incense, trim the lamps, and offer the head and the hind leg of the sacrifices.[57] They brought sages from the court to the High Priest, and throughout the seven days they read to him about the order of the service. They asked the High Priest to read it aloud, in case he had forgotten or never learned.[58]

The Mishnah taught that on the morning of the day before Yom Kippur, they placed the High Priest at the Eastern Gate and brought before him oxen, rams, and sheep, so that he could become familiar with the service.[58] The rest of the seven days, they did not withhold food or drink from him, but near nightfall on the eve of Yom Kippur, they would not let him eat much, as food might make him sleep.[59] The sages of the court took him up to the house of Avtinas and handed him over to the elders of the priesthood. As the sages of the court took their leave, they cautioned him that he was the messenger of the court, and adjured him in God's Name that he not change anything in the service from what they had told him. He and they turned aside and wept that they should have to suspect him of doing so.[60]

The Mishnah taught that on the night before Yom Kippur, if the High Priest was a sage, he would expound the relevant Scriptures, and if he was not a sage, the disciples of the sages would expound before him. If he was used to reading the Scriptures, he would read, and if he was not, they would read before him. They would read from Job, Ezra, and Chronicles, and Zechariah ben Kubetal said from Daniel.[61] If he tried to sleep, young priests would snap their middle finger before him and say, "Mr. High Priest, arise and drive the sleep away!" They would keep him busy until near the time for the morning offering.[62]

On any other day, a priest would remove the ashes from the altar at about the time of the cock's crow (in accordance with Leviticus 6:3). But for Yom Kippur, the ashes were removed beginning at midnight of the night before. Before the cock's crow approached, Israelites filled the Temple Court.[63] The officer told the priests to see whether the time for the morning sacrifice had arrived. If it had, then the priest who saw it would call out, "It's daylight!"[64]

They led the High Priest down to the place of immersion (the mikveh).[65] During the day of Yom Kippur, the High Priest would immerse himself five times and wash his hands and feet ten times. Except for this first immersion, he would do each on holy ground in the Parwah cell.[66] They spread a linen sheet between him and the people.[67] If the High Priest was either old or delicate, they warmed the water for him.[68] He undressed, immersed himself, came up, and dried off. They brought him the golden garments; he put them on and washed his hands and feet.[69]

They brought him the continual offering; he cut its throat, and another priest finished slaughtering it. The High Priest received the blood and sprinkled it on the altar. He entered the Sanctuary, burned the morning incense, and trimmed the lamps. Then he offered up the head, limbs, cakes, and wine-offering.[69]

They brought him to the Parwah cell, spread a sheet of linen between him and the people, he washed his hands and feet, and undressed. (Rabbi Meir said that he undressed first and then washed his hands and feet.) Then he went down and immersed himself for the second time, came up and dried himself. They brought him white garments (as required by Leviticus 16:4). He put them on and washed his hands and feet.[70] Rabbi Meir taught that in the morning, he wore Pelusium linen worth 12 minas, and in the afternoon he wore Indian linen worth 800 zuz. But the sages said that in the morning, he wore garments worth 18 minas, and in the afternoon he wore garments worth 12 minas. The community paid for these sums, and the High Priest could spend more from his own funds if he wanted to.[71]

Rav Ḥisda asked why Leviticus 16:4 instructed the High Priest to enter the inner precincts (the Kodesh Hakodashim) to perform the Yom Kippur service in linen vestments instead of gold. Rav Ḥisda taught that it was because the accuser may not act as defender. Gold played the accuser because it was used in the Golden Calf, and thus gold was inappropriate for the High Priest when he sought atonement and thus played the defender.[72]

A Midrash taught that everything God created in heaven has a replica on earth. (And thus, since all that is above is also below, God dwells on earth just as God dwells in heaven.) Referring to a heavenly man, Ezekiel 9:11 says, "And, behold, the man clothed in linen." And of the High Priest on earth, Leviticus 16:4 says, "He shall put on the holy linen tunic." And the Midrash taught that God holds the things below dearer than those above, for God left the things in heaven to descend to dwell among those below, as Exodus 25:8 reports, "And let them make Me a sanctuary, that I may dwell among them."[73]

A Midrash taught that Leviticus 16:4 alludes to the merit of the Matriarchs by mentioning linen four times.[74]

The Mishnah taught that the High Priest came to his bull (as required in Leviticus 16:3 and 6), which was standing between the hall and the altar with its head to the south and its face to the west. The High Priest stood on the east with his face to the west. And he pressed both his hands on the bull and made confession, saying: "O Lord! I have done wrong, I have transgressed, I have sinned before You, I and my house. O Lord! Forgive the wrongdoings, the transgressions, and the sins that I have committed, transgressed, and sinned before You, I and my house, as it is written in the Torah of Moses Your servant (in Leviticus 16:30): "For on this day shall atonement be made for you to cleanse you; from all your sins shall you be clean before the Lord." And the people answered: "Blessed is the Name of God's glorious Kingdom, forever and ever!"[75]

Rabbi Isaac contrasted the red cow in Numbers 19:3–4 and the bull that the High Priest brought for himself on Yom Kippur in Leviticus 16:3–6. Rabbi Isaac taught that a lay Israelite could slaughter one of the two, but not the other, but Rabbi Isaac did not know which was which. The Gemara reported that Rav and Samuel disagreed about the answer. Rav held it invalid for a lay Israelite to slaughter the red cow and valid for a lay Israelite to slaughter the High Priest's bull, while Samuel held it invalid for a lay Israelite to slaughter the High Priest's bull and valid for a lay Israelite to slaughter the red cow. The Gemara reported that Rav Zeira (or some say Rav Zeira in the name of Rav) said that the slaughtering of the red cow by a lay Israelite was invalid, and Rav deduced from this statement the importance that Numbers 19:3 specifies "Eleazar" and Numbers 19:2 specifies that the law of the red cow is a "statute" (and thus required precise execution). But the Gemara challenged Rav's conclusion that the use of the terms "Eleazar" and "statute" in Numbers 19:2–3 in connection with the red cow decided the matter, for in connection with the High Priest's bull, Leviticus 16:3 specifies "Aaron," and Leviticus 16:34 calls the law of Leviticus 16 a "statute," as well. The Gemara supposed that the characterization of Leviticus 16:34 of the law as a "statute" might apply to only the Temple services described in Leviticus 16, and the slaughtering of the High Priest's bull might be regarded as not a Temple service. But the Gemara asked whether the same logic might apply to the red cow, as well, as it was not a Temple service, either. The Gemara posited that one might consider the red cow to have been in the nature of an offering for Temple upkeep. Rav Shisha son of Rav Idi taught that the red cow was like the inspection of skin diseases in Leviticus 13–14, which was not a Temple service, yet required a priest's participation. The Gemara then turned to Samuel's position, that a lay Israelite could kill the red cow. Samuel interpreted the words "and he shall slay it before him" in Numbers 19:3 to mean that a lay Israelite could slaughter the cow as Eleazar watched. The Gemara taught that Rav, on the other hand, explained the words "and he shall slay it before him" in Numbers 19:3 to enjoin Eleazar not to divert his attention from the slaughter of the red cow. The Gemara reasoned that Samuel deduced that Eleazer must not divert his attention from the words "and the heifer shall be burnt in his sight" in Numbers 19:5 (which one could similarly read to imply an injunction for Eleazar to pay close attention). And Rav explained the words "in his sight" in one place to refer to the slaughtering, and in the other to the burning, and the law enjoined his attention to both. In contrast, the Gemara posited that Eleazar might not have needed to pay close attention to the casting in of cedarwood, hyssop, and scarlet, because they were not part of the red cow itself.[76]

A Midrash taught that God showed Abraham the bullock that Leviticus 16:3–19 would require the Israelites to sacrifice on the Yom Kippur. Reading Genesis 15:9, “And He said to him: ‘Take me a heifer of three years old (מְשֻׁלֶּשֶׁת, meshuleshet), a she-goat of three years old (מְשֻׁלֶּשֶׁת, meshuleshet), and a ram of three years old (מְשֻׁלָּשׁ, meshulash),’” the Midrash read מְשֻׁלֶּשֶׁת, meshuleshet, to mean “three-fold” or “three kinds,” indicating sacrifices for three different purposes. The Midrash deduced that God thus showed Abraham three kinds of bullocks, three kinds of goats, and three kinds of rams that Abraham’s descendants would need to sacrifice. The three kinds of bullocks were: (1) the bullock that Leviticus 16:3–19 would require the Israelites to sacrifice on Yom Kippur, (2) the bullock that Leviticus 4:13–21 would require the Israelites to bring on account of unwitting transgression of the law, and (3) the heifer whose neck Deuteronomy 21:1–9 would require the Israelites to break. The three kinds of goats were: (1) the goats that Numbers 28:16–29:39 would require the Israelites to sacrifice on festivals, (2) the goats that Numbers 28:11–15 would require the Israelites to sacrifice on the New Moon (ראש חודש, Rosh Chodesh), and (3) the goat that Leviticus 4:27–31 would require an individual to bring. The three kinds of rams were: (1) the guilt-offering of certain obligation that Leviticus 5:25, for example, would require one who committed a trespass to bring, (2) the guilt-offering of doubt to which one would be liable when in doubt whether one had committed a transgression, and (3) the lamb to be brought by an individual. Rabbi Simeon bar Yohai said that God showed Abraham all the atoning sacrifices except for the tenth of an ephah of fine meal in Leviticus 5:11. The Rabbis said that God showed Abraham the tenth of an ephah as well, for Genesis 15:10 says “all these (אֵלֶּה, eleh),” just as Leviticus 2:8 says, “And you shall bring the meal-offering that is made of these things (מֵאֵלֶּה, me-eleh),” and the use of “these” in both verses hints that both verses refer to the same thing. And reading Genesis 15:10, “But the bird divided he not,” the Midrash deduced that God intimated to Abraham that the bird burnt-offering would be divided, but the bird sin-offering (which the dove and young pigeon symbolized) would not be divided.[77]

The Mishnah taught that High Priest then went back to the east of the Temple Court, north of the altar. The two goats required by Leviticus 16:7 were there, as was an urn containing two lots. The urn was originally made of boxwood, but Ben Gamala remade them in gold, earning him praise.[78] Rabbi Judah explained that Leviticus 16:7 mentioned the two goats equally because they should be alike in color, height, and value.[79] The Mishnah taught that the High Priest shook the urn and brought up the two lots. On one lot was inscribed "for the Lord," and on the other "for Azazel." The Deputy High Priest stood at the High Priest's right hand and the head of the ministering family at his left. If the lot inscribed "for the Lord" came up in his right hand, the Deputy High Priest would say "Mr. High Priest, raise your right hand!" And if the lot inscribed "for the Lord" came up in his left hand, the head of the family would say "Mr. High Priest, raise your left hand!" Then he placed them on the goats and said: "A sin-offering ‘to the Lord!'" (Rabbi Ishmael taught that he did not need to say "a sin-offering" but just "to the Lord.") And then the people answered "Blessed is the Name of God's glorious Kingdom, forever and ever!"[80]

Then the High Priest bound a thread of crimson wool on the head of the Azazel goat, and placed it at the gate from which it was to be sent away. And he placed the goat that was to be slaughtered at the slaughtering place. He came to his bull a second time, pressed his two hands on it and made confession, saying: "O Lord, I have dealt wrongfully, I have transgressed, I have sinned before You, I and my house, and the children of Aaron, Your holy people, o Lord, pray forgive the wrongdoings, the transgression, and the sins that I have committed, transgressed, and sinned before You, I and my house, and the children of Aaron, Your holy people. As it is written in the Torah of Moses, Your servant (in Leviticus 16:30): ‘For on this day atonement be made for you, to cleanse you; from all the sins shall you be clean before the Lord.'" And then the people answered: "Blessed is the Name of God's glorious Kingdom, forever and ever!"[81] Then he killed the bull.[82]

Rabbi Isaac noted two red threads, one in connection with the red cow in Numbers 19:6, and the other in connection with the scapegoat in the Yom Kippur service of Leviticus 16:7–10 (which Mishnah Yoma 4:2 indicates was marked with a red thread[81]). Rabbi Isaac had heard that one required a definite size, while the other did not, but he did not know which was which. Rav Joseph reasoned that because (as Mishnah Yoma 6:6 explains[83]) the red thread of the scapegoat was divided, that thread required a definite size, whereas that of the red cow, which did not need to be divided, did not require a definite size. Rami bar Hama objected that the thread of the red cow required a certain weight (to be cast into the flames, as described in Numbers 19:6). Raba said that the matter of this weight is disputed by Tannaim.[84]

When Rav Dimi came from the Land of Israel, he said in the name of Rabbi Johanan that there were three red threads: one in connection with the red cow, the second in connection with the scapegoat, and the third in connection with the person with skin disease (the m'tzora) in Leviticus 14:4. Rav Dimi reported that one weighed ten zuz, another weighed two selas, and the third weighed a shekel, but he could not say which was which. When Rabin came, he said in the name of Rabbi Jonathan that the thread in connection with the red cow weighed ten zuz, that of the scapegoat weighed two selas, and that of the person with skin disease weighed a shekel. Rabbi Johanan said that Rabbi Simeon ben Halafta and the Sages disagreed about the thread of the red cow, one saying that it weighed ten shekels, the other that it weighed one shekel. Rabbi Jeremiah of Difti said to Ravina that they disagreed not about the thread of the red cow, but about that of the scapegoat.[85]

Reading Leviticus 18:4, "My ordinances (מִשְׁפָּטַי, mishpatai) shall you do, and My statutes (חֻקֹּתַי, chukotai) shall you keep," the Sifra distinguished "ordinances" (מִשְׁפָּטִים, mishpatim) from "statutes" (חֻקִּים, chukim). The term "ordinances" (מִשְׁפָּטִים, mishpatim), taught the Sifra, refers to rules that even had they not been written in the Torah, it would have been entirely logical to write them, like laws pertaining to theft, sexual immorality, idolatry, blasphemy and murder. The term "statutes" (חֻקִּים, chukim), taught the Sifra, refers to those rules that the impulse to do evil (יצר הרע, yetzer hara) and the nations of the world try to undermine, like eating pork (prohibited by Leviticus 11:7 and Deuteronomy 14:7–8), wearing wool-linen mixtures (שַׁעַטְנֵז, shatnez, prohibited by Leviticus 19:19 and Deuteronomy 22:11), release from levirate marriage (חליצה, chalitzah, mandated by Deuteronomy 25:5–10), purification of a person affected by skin disease (מְּצֹרָע, metzora, regulated in Leviticus 13–14), and the goat sent off into the wilderness (the scapegoat regulated in Leviticus 16:7–22). In regard to these, taught the Sifra, the Torah says simply that God legislated them and we have no right to raise doubts about them.[86]

Similarly, Rabbi Joshua of Siknin taught in the name of Rabbi Levi that the Evil Inclination (יצר הרע, yetzer hara) criticizes four laws as without logical basis, and Scripture uses the expression "statute" (chuk) in connection with each: the laws of (1) a brother's wife (in Deuteronomy 25:5–10), (2) mingled kinds (in Leviticus 19:19 and Deuteronomy 22:11), (3) the scapegoat (in Leviticus 16:7–22), and (4) the red cow (in Numbers 19).[87]

The Mishnah taught that the High Priest said a short prayer in the outer area.[88] The Jerusalem Talmud taught that this was the prayer of the High Priest on the Day of Atonement, when he left the Holy Place whole and in one piece: “May it be pleasing before you, Lord, our God of our fathers, that a decree of exile not be issued against us, not this day or this year, but if a decree of exile should be issued against us, then let it be exile to a place of Torah. May it be pleasing before you, Lord, our God and God of our fathers, that a decree of want not be issued against us, not this day or this year, but if a decree of want should be issued against us, then let it be a want because of the performance of religious duties. May it be pleasing before you, Lord, our God and God of our fathers, that this year be a year of cheap food, full bellies, good business; a year in which the earth forms clods, then is parched so as to form scabs, and then moistened with dew, so that your people, Israel, will not be in need of the help of one another. And do not heed the prayer of travelers that it not rain.” The Rabbis of Caesarea added, “And concerning your people, Israel, that they not exercise dominion over one another.” And for the people who live in the Sharon plain he would say this prayer, “May it be pleasing before you, Lord, our God and God of our fathers, that our houses not turn into our graves.”[89]

The Mishnah taught that one would bring the High Priest the goat to be slaughtered, he would kill it, receive its blood in a basin, enter again the Sanctuary, and would sprinkle once upwards and seven times downwards. He would count: "one," "one and one," "one and two," and so on. Then he would go out and place the vessel on the second golden stand in the sanctuary.[90]

Then the High Priest came to the scapegoat and laid his two hands on it, and he made confession, saying: "I beseech You, o Lord, Your people the house of Israel have failed, committed iniquity and transgressed before you. I beseech you, o Lord, atone the failures, the iniquities and the transgressions that Your people, the house of Israel, have failed, committed, and transgressed before you, as it is written in the Torah of Moses, Your servant (in Leviticus 16:30): ‘For on this day shall atonement be made for you, to cleanse you; from all your sins shall you be clean before the Lord.'" And when the Priests and the people standing in the Temple Court heard the fully pronounced Name of God come from the mouth of the High Priest, they bent their knees, bowed down, fell on their faces, and called out: "Blessed is the Name of God's glorious Kingdom, forever and ever!"[91]

The Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer taught that Sammael (identified with Satan) complained to God that God had given him power over all the nations of the world except for Israel. God told Sammael that he had power over Israel on the Day of Atonement if and only if they had any sin. Therefore, Israel gave Sammael a present on the Day of Atonement, as Leviticus 16:8 says, "One lot for the Lord, and the other lot for Azazel" (identified with Satan or Sammael). The lot for God was the offering of a burnt offering, and the lot for Azazel was the goat as a sin offering, for all the iniquities of Israel were upon it, as Leviticus 16:22 says, "And the goat shall bear upon him all their iniquities." Sammael found no sin among them on the Day of Atonement and complained to God that they were like the ministering angels in heaven. Just as the ministering angels have bare feet, so have the Israelites bare feet on the Day of Atonement. Just as the ministering angels have neither food nor drink, so the Israelites have neither food nor drink on the Day of Atonement. Just as the ministering angels have no joints, likewise the Israelites stand on their feet. Just as the ministering angels are at peace with each other, so the Israelites are at peace with each other on the Day of Atonement. Just as the ministering angels are innocent of all sin on the Day of Atonement, so are the Israelites innocent of all sin on the Day of Atonement. On that day, God hears their prayers rather than the charges of their accuser, and God makes atonement for all the people, as Leviticus 16:16 says, "And he shall make atonement for the holy place."[92]

Reading the injunction of Leviticus 16:11, "And he shall make atonement for himself, and for his house," a Midrash taught that a man without a wife dwells without good, without help, without joy, without blessing, and without atonement. Without good, as Genesis 2:18 says that "it is not good that the man should be alone." Without help, as in Genesis 2:18, God says, "I will make him a help meet for him." Without joy, as Deuteronomy 14:26 says, "And you shall rejoice, you and your household" (implying that one can rejoice only when there is a "household" with whom to rejoice). Without a blessing, as Ezekiel 44:30 can be read, "To cause a blessing to rest on you for the sake of your house" (that is, for the sake of your wife). Without atonement, as Leviticus 16:11 says, "And he shall make atonement for himself, and for his house" (implying that one can make complete atonement only with a household). Rabbi Simeon said in the name of Rabbi Joshua ben Levi, without peace too, as 1 Samuel 25:6 says, "And peace be to your house." Rabbi Joshua of Siknin said in the name of Rabbi Levi, without life too, as Ecclesiastes 9:9 says, "Enjoy life with the wife whom you love." Rabbi Hiyya ben Gomdi said, also incomplete, as Genesis 5:2 says, "male and female created He them, and blessed them, and called their name Adam," that is, "man" (and thus only together are they "man"). Some say a man without a wife even impairs the Divine likeness, as Genesis 9:6 says, "For in the image of God made He man," and immediately thereafter Genesis 9:7 says, "And you, be fruitful, and multiply (implying that the former is impaired if one does not fulfill the latter).[93]

The Mishnah taught that they handed the scapegoat over to him who was to lead it away. All were permitted to lead it away, but the Priests made it a rule not to permit an ordinary Israelite to lead it away. Rabbi Jose said that Arsela of Sepphoris once led it away, although he was not a priest.[94] The people went with him from booth to booth, except the last one. The escorts would not go with him up to the precipice, but watched from a distance.[95] The one leading the scapegoat divided the thread of crimson wool, and tied one half to the rock, the other half between the scapegoat horns, and pushed the scapegoat from behind. And it went rolling down and before it had reached half its way down the hill, it was dashed to pieces. He came back and sat down under the last booth until it grew dark. His garments unclean become unclean from the moment that he has gone outside the wall of Jerusalem, although Rabbi Simeon taught that they became unclean from the moment that he pushed it over the precipice.[83]

The Sages taught that if one pushed the goat down the precipice and it did not die, then one had to go down after the goat and kill it.[96]

The Mishnah interpreted Leviticus 16:21 to teach that the goat sent to Azazel could atone for all sins, even sins punishable by death.[97]

They would set up guards at stations, and from these would waive towels to signal that the goat had reached the wilderness. When the signal was relayed to Jerusalem, they told the High Priest: "The goat has reached the wilderness." Rabbi Ishmael taught that they had another sign too: They tied a thread of crimson to the door of the Temple, and when the goat reached the wilderness, the thread would turn white, as it is written in Isaiah 1:18: "Though your sins be as scarlet, they shall be as white as snow."[98]

The Mishnah compared the person who burned the red cow in Numbers 19:8, the person who burned the bulls burned pursuant to Leviticus 4:3–21 or 16:27, and the person who led away the scapegoat pursuant to Leviticus 16:7–10 and 26. These persons rendered unclean the clothes worn while doing these acts. But the red cow, the bull, and the scapegoat did not themselves render unclean clothes with which they came in contact. The Mishnah imagined the clothing saying to the person: "Those that render you unclean do not render me unclean, but you render me unclean."[99]

Rabbi Hanina noted that for all the vessels that Moses made, the Torah gave the measurements of their length, breadth, and height (in Exodus 25:23 for the altar, Exodus 27:1 for the table, and Exodus 30:2 for the incense altar). But for the Ark-cover, Exodus 25:17 gave its length and breadth, but not its height. Rabbi Hanina taught that one can deduce the Ark-cover's height from the smallest of the vessel features, the border of the table, concerning which Exodus 25:25 says, "And you shall make for it a border of a handbreadth round about." Just as the height of the table's border was a handbreadth, so was it also for the Ark-cover. Rav Huna taught that the height of the Ark-cover may be deduced from Leviticus 16:14, which refers to "the face of the Ark-cover," and a "face" cannot be smaller than a handbreadth. Rav Aha bar Jacob taught a tradition that the face of the cherubim was not less than a handbreadth, and Rav Huna also made his deduction about the Ark-cover's height from the parallel.[100]

Rabbi Eliezer noted that both Leviticus 16:27 (with regard to burning the Yom Kippur sin offerings) and Numbers 19:3 (with regard to slaughtering the red cow) say "outside the camp." Rabbi Eliezer concluded that both actions had to be conducted outside the three camps of the Israelites, and in the time of the Temple in Jerusalem, both actions had to be conducted to the east of Jerusalem.[101]

Chapter 8 of tractate Yoma in the Mishnah and Babylonian Talmud and chapter 4 of tractate Kippurim (Yoma) in the Tosefta interpreted the laws of self-denial in Leviticus 16:29–34 and 23:26–32.[102] The Mishnah taught that on Yom Kippur, one must not eat, drink, wash, anoint oneself, put on sandals, or have sexual intercourse. Rabbi Eliezer (whom the halachah follows) taught that a king or bride may wash the face, and a woman after childbirth may put on sandals. But the sages forbad doing so.[103] The Tosefta taught that one must not put on even felt shoes. But the Tosefta taught that minors can do all these things except put on sandals, for appearance's sake.[104] The Mishnah held a person culpable to punishment for eating an amount of food equal to a large date (with its pit included), or for drinking a mouthful of liquid. For the purpose of calculating the amount consumed, one combines all amounts of food together, and all amounts liquids together, but not amounts of foods together with amounts of liquids.[105] The Mishnah obliged one who unknowingly or forgetfully ate and drank to bring only one sin-offering. But one who unknowingly or forgetfully ate and performed labor had to bring two sin-offerings. The Mishnah did not hold one culpable who ate foods unfit to eat, or drank liquids unfit to drink (like fish-brine).[106] The Mishnah taught that one should not afflict children at all on Yom Kippur. In the two years before they become Bar or Bat Mitzvah, one should train children to become used to religious observances (for example by fasting for several hours).[107] The Mishnah taught that one should give food to a pregnant woman who smelled food and requested it. One should feed to a sick person at the direction of experts, and if no experts are present, one feeds a sick person who requests food.[108] The Mishnah taught that one may even give unclean food to one seized by a ravenous hunger, until the person's eyes are opened. Rabbi Matthia ben Heresh said that one who has a sore throat may drink medicine even on the Sabbath, because it presented the possibility of danger to human life, and every danger to human life suspends the laws of the Sabbath.[109]

Rav Ḥisda taught that the five afflictions of Yom Kippur that the Mishnah taught (eating and in drinking, bathing, smearing the body with oil, wearing shoes, and conjugal relations) are based on the five times that the Torah mentions the afflictions of Yom Kippur: (1) “And on the tenth of this seventh month you shall have a holy convocation, and you shall afflict your souls” (Numbers 29:7); (2) “But on the tenth of this seventh month is the day of atonement, it shall be a holy convocation for you and you shall afflict your souls” (Leviticus 23:27); (3) “It shall be for you a Shabbat of solemn rest, and you shall afflict your souls (Leviticus 23:32); (4) “It is a Shabbat of solemn rest for you, and you shall afflict your souls” (Leviticus 16:31); (5) “And it shall be a statute for you forever, in the seventh month on the tenth of the month, you shall afflict your souls” (Leviticus 16:29).[110]

Rabbi Akiva (or some say Rabban Johanan ben Zakai) never said in the house of study that it was time to stop studying, except on the eve of Passover and the eve of the Yom Kippur. On the eve of Passover, it was because of the children, so that they might not fall asleep, and on the eve of the Day of Atonement, it was so that they should feed their children before the fast.[111]

The Gemara taught that in conducting the self-denial required in Leviticus 16:29–34 and 23:26–32, one adds a little time from the surrounding ordinary weekdays to the holy day. Rabbi Ishmael derived this rule from what had been taught in a Baraita: One might read Leviticus 23:32, "And you shall afflict your souls on the ninth day," literally to mean that one begins fasting the entire day on the ninth day of the month; Leviticus 23:32 therefore says, "in the evening." One might read "in the evening" to mean "after dark" (which the Hebrew calendar would reckon as part of the tenth day); Leviticus 23:32 therefore says, "in the ninth day." The Gemara thus concluded that one begins fasting while it is still day on the ninth day, adding some time from the profane day (the ninth) to the holy day (the tenth). The Gemara read the words, "from evening to evening," in Leviticus 23:32 to teach that one adds some time to Yom Kippur from both the evening before and the evening after. Because Leviticus 23:32 says, "You shall rest," the Gemara applied the rule to Sabbaths as well. Because Leviticus 23:32 says "your Sabbath" (your day of rest), the Gemara applied the rule to other Festivals (in addition to Yom Kippur); wherever the law creates an obligation to rest, we add time to that obligation from the surrounding profane days to the holy day. Rabbi Akiva, however, read Leviticus 23:32, "And you shall afflict your souls on the ninth day," to teach the lesson learned by Rav Hiyya bar Rav from Difti (that is, Dibtha, below the Tigris, southeast of Babylon). Rav Hiyya bar Rav from Difti taught in a Baraita that Leviticus 23:32 says "the ninth day" to indicate that if people eat and drink on the ninth day, then Scripture credits it to them as if they fasted on both the ninth and the tenth days (because Leviticus 23:32 calls the eating and drinking on the ninth day "fasting").[112]

The Gemara read the definite article in the term "the homeborn" in Leviticus 16:29 to include women in the extension of the period of affliction to Yom Kippur eve.[113]

The Jerusalem Talmud taught that the evil impulse (יצר הרע, yetzer hara) craves only what is forbidden. The Jerusalem Talmud illustrated this by relating that on the Day of Atonement, Rabbi Mana went to visit Rabbi Haggai, who was feeling weak. Rabbi Haggai told Rabbi Mana that he was thirsty. Rabbi Mana told Rabbi Haggai to go drink something. Rabbi Mana left and after a while came back. Rabbi Mana asked Rabbi Haggai what happened to his thirst. Rabbi Haggai replied that when Rabbi Mana told him that he could drink, his thirst went away.[114]

The Mishnah taught that death and observance of Yom Kippur with penitence atone for sin. Penitence atones for lighter sins, while for severer sins, penitence suspends God's punishment, until Yom Kippur comes to atone.[115] The Mishnah taught that no opportunity for penance will be given to one who says: "I shall sin and repent, sin and repent." And Yom Kippur does not atone for one who says: "I shall sin and Yom Kippur will atone for me." Rabbi Eleazar ben Azariah derived from the words "From all your sins before the Lord shall you be clean" in Leviticus 16:30 that Yom Kippur atones for sins against God, but Yom Kippur does not atone for transgressions between one person and another, until the one person has pacified the other. Rabbi Akiva said that Israel is fortunate, for just as waters cleanse the unclean, so does God cleanse Israel.[116]

Rabbi Eleazar interpreted the words of Leviticus 16:30, "from all your sins shall you be clean before the Lord," to teach that the Day of Atonement expiates sins that are known only to God.[117]

Rabbi Eleazer son of Rabbi Simeon taught that the Day of Atonement effects atonement even if no goat is offered. But the goat effected atonement only with the Day of Atonement.[118]

Mar Zutra taught that the merit of a fast day lies in the charity dispensed.[119]

The Gemara told that a poor man lived in Mar Ukba's neighborhood to whom he regularly sent 400 zuz on the eve of every Yom Kippur. Once Mar Ukba sent his son to deliver the 400 zuz. His son came back and reported that the poor man did not need Mar Ukba's help. When Mar Ukba asked his son what he had seen, his son replied that they were sprinkling aged wine before the poor man to improve the aroma in the room. Mar Ukba said that if the poor man was that delicate, then Mar Ukba would double the amount of his gift and send it back to the poor man.[120]

Rabbi Eleazar taught that when the Temple stood, a person used to bring a shekel and so make atonement. Now that the Temple no longer stands, if people give to charity, all will be well, and if they do not, heathens will come and take from them forcibly (what they should have given away). And even so, God will reckon to them as if they had given charity, as Isaiah 60:17 says, "I will make your exactors righteousness [צְדָקָה, tzedakah]."[121]

Rav Bibi bar Abaye taught that on the eve of the Day of Atonement, a person should confess saying: "I confess all the evil I have done before You; I stood in the way of evil; and as for all the evil I have done, I shall no more do the like; may it be Your will, O Lord my God, that You should pardon me for all my iniquities, and forgive me for all my transgressions, and grant me atonement for all my sins." This is indicated by Isaiah 55:7, which says, "Let the wicked forsake his way, and the man of iniquity his thoughts." Rabbi Isaac compared it to a person fitting together two boards, joining them one to another. And Rabbi Jose ben Hanina compared it to a person fitting together two bed-legs, joining them one to another. (This harmoniously does a person become joined to God when the person genuinely repents.)[122]

The Rabbis taught that the obligation to confess sins comes on the eve of the Day of Atonement, as it grows dark. But the Sages said that one should confess before one has eaten and drunk, lest one become inebriated in the course of the meal. And even if one has confessed before eating and drinking, one should confess again after having eaten and drunk, because perhaps some wrong happened during the meal. And even if one has confessed during the evening prayer, one should confess again during the morning prayer. And even if one has confessed during the morning prayer, one should do so again during the Musaf additional prayer. And even if one has confessed during the Musaf, one should do so again during the afternoon prayer. And even if one has done so in the afternoon prayer, one should confess again in the Ne'ilah concluding prayer. The Gemara taught that the individual should say the confession after the (silent recitation of the) Amidah prayer, and the public reader says it in the middle of the Amidah. Rav taught that the confession begins: "You know the secrets of eternity . . . ." Samuel, however, taught that the confession begins: "From the depths of the heart . . . ." Levi said: "And in Your Torah it is said, [‘For on this day He shall make atonement for you.']" (Leviticus 16:30.) Rabbi Johanan taught that the confession begins: "Lord of the Universe, . . . ." Rav Judah said: "Our iniquities are too many to count, and our sins too numerous to be counted." Rav Hamnuna said: "My God, before I was formed, I was of no worth, and now that I have been formed, it is as if I had not been formed. I am dust in my life, how much more in my death. Behold, I am before You like a vessel full of shame and reproach. May it be Your will that I sin no more, and what I have sinned wipe away in Your mercy, but not through suffering." That was the confession of sins used by Rav all the year round, and by Rav Hamnuna the younger, on the Day of Atonement. Mar Zutra taught that one should say such prayers only if one has not already said, "Truly, we have sinned," but if one has said, "Truly, we have sinned," no more is necessary. For Bar Hamdudi taught that once he stood before Samuel, who was sitting, and when the public reader said, "Truly, we have sinned," Samuel rose, and so Bar Hamdudi inferred that this was the main confession.[123]

Resh Lakish taught that great is repentance, for because of it, Heaven accounts premeditated sins as errors, as Hosea 14:2 says, "Return, O Israel, to the Lord, your God, for you have stumbled in your iniquity." "Iniquity" refers to premeditated sins, and yet Hosea calls them "stumbling," implying that Heaven considers those who repent of intentional sins as if they acted accidentally. But the Gemara said that that is not all, for Resh Lakish also said that repentance is so great that with it, Heaven accounts premeditated sins as though they were merits, as Ezekiel 33:19 says, "And when the wicked turns from his wickedness, and does that which is lawful and right, he shall live thereby." The Gemara reconciled the two positions, clarifying that in the sight of Heaven, repentance derived from love transforms intentional sins to merits, while repentance out of fear transforms intentional sins to unwitting transgressions.[124]

Reading Song of Songs 6:11, Rabbi Joshua ben Levi compared Israel to a nut-tree. Rabbi Azariah taught that just as when a nut falls into the dirt, you can wash it, restore it to its former condition, and make it fit for eating, so however much Israel may be defiled with iniquities all the rest of the year, when the Day of Atonement comes, it makes atonement for them, as Leviticus 16:30 says, "For on this day shall atonement be made for you, to cleanse you."[125]

The Mishnah taught that Divine judgment is passed on the world at four seasons (based on the world's actions in the preceding year) — at Passover for produce; at Shavuot for fruit; at Rosh Hashanah all creatures pass before God like children of maron (one by one), as Psalm 33:15 says, "He Who fashions the heart of them all, Who considers all their doings." And on Sukkot, judgment is passed in regard to rain.[126] Rabbi Meir taught that all are judged on Rosh Hashanah and the decree is sealed on Yom Kippur. Rabbi Judah, however, taught that all are judged on Rosh Hashanah and the decree of each and every one of them is sealed in its own time — at Passover for grain, at Shavuot for fruits of the orchard, at Sukkot for water. And the decree of humankind is sealed on Yom Kippur. Rabbi Jose taught that humankind is judged every single day, as Job 7:17–18 says, "What is man, that You should magnify him, and that You should set Your heart upon him, and that You should remember him every morning, and try him every moment?"[127]

Rav Kruspedai said in the name of Rabbi Johanan that on Rosh Hashanah, three books are opened in Heaven — one for the thoroughly wicked, one for the thoroughly righteous, and one for those in between. The thoroughly righteous are immediately inscribed definitively in the book of life. The thoroughly wicked are immediately inscribed definitively in the book of death. And the fate of those in between is suspended from Rosh Hashanah to Yom Kippur. If they deserve well, then they are inscribed in the book of life; if they do not deserve well, then they are inscribed in the book of death. Rabbi Abin said that Psalm 69:29 tells us this when it says, "Let them be blotted out of the book of the living, and not be written with the righteous." "Let them be blotted out from the book" refers to the book of the wicked. "Of the living" refers to the book of the righteous. "And not be written with the righteous" refers to the book of those in between. Rav Nahman bar Isaac derived this from Exodus 32:32, where Moses told God, "if not, blot me, I pray, out of Your book that You have written." "Blot me, I pray" refers to the book of the wicked. "Out of Your book" refers to the book of the righteous. "That you have written" refers to the book of those in between. It was taught in a Baraita that the House of Shammai said that there will be three groups at the Day of Judgment — one of thoroughly righteous, one of thoroughly wicked, and one of those in between. The thoroughly righteous will immediately be inscribed definitively as entitled to everlasting life; the thoroughly wicked will immediately be inscribed definitively as doomed to Gehinnom, as Daniel 12:2 says, "And many of them who sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life and some to reproaches and everlasting abhorrence." Those in between will go down to Gehinnom and scream and rise again, as Zechariah 13:9 says, "And I will bring the third part through the fire, and will refine them as silver is refined, and will try them as gold is tried. They shall call on My name and I will answer them." Of them, Hannah said in 1 Samuel 2:6, "The Lord kills and makes alive, He brings down to the grave and brings up." The House of Hillel, however, taught that God inclines the scales towards grace (so that those in between do not have to descend to Gehinnom), and of them David said in Psalm 116:1–3, "I love that the Lord should hear my voice and my supplication . . . The cords of death compassed me, and the straits of the netherworld got hold upon me," and on their behalf David composed the conclusion of Psalm 116:6, "I was brought low and He saved me."[128]

Rav Mana of Sha'ab (in Galilee) and Rav Joshua of Siknin in the name of Rav Levi compared repentance at the High Holidays to the case of a province that owed arrears on its taxes to the king, and the king came to collect the debt. When the king was within ten miles, the nobility of the province came out and praised him, so he freed the province of a third of its debt. When he was within five miles, the middle-class people of the province came out and praised him, so he freed the province of another third of its debt. When he entered the province, all the people of the province — men, women, and children — came out and praised him, so he freed them of all of their debt. The king told them to let bygones be bygones; from then on they would start a new account. In a similar manner, on the eve of Rosh Hashanah, the leaders of the generation fast, and God absolves them of a third of their iniquities. From Rosh Hashanah to Yom Kippur, private individuals fast, and God absolves them of a third of their iniquities. On Yom Kippur, everyone fasts — men, women and children — and God tells Israel to let bygones be bygones; from then onwards we begin a new account. From Yom Kippur to Sukkot, all Israel are busy with the performance of religious duties. One is busy with a sukkah, one with a lulav. On the first day of Sukkot, all Israel stand in the presence of God with their palm-branches and etrogs in honor of God's name, and God tells them to let bygones be bygones; from now we begin a new account. Thus in Leviticus 23:40, Moses exhorts Israel: "You shall take on the first day [of Sukkot] the fruit of goodly trees, branches of palm trees and the boughs of thick trees, and willows of the brook; and you shall rejoice before the Lord your God." Rabbi Aha explained that the words, "For with You there is forgiveness," in Psalm 130:4signify that forgiveness waits with God from Rosh Hashanah onward. And forgiveness waits that long so (in the words of Psalm 130:4) "that You may be feared" and God may impose God's awe upon God's creatures (through the suspense and uncertainty).[129]

Rabban Simeon ben Gamaliel said that there never were greater days of joy in Israel than the 15th of Av and Yom Kippur. On those days, the daughters of Jerusalem would come out in borrowed white garments, dance in the vineyards, and exclaim to the young men to lift up their eyes and choose for themselves.[130]

A Baraita noted a difference in wording between Exodus 29:30, regarding the investiture of the High Priest, and Leviticus 16:32, regarding the qualifications for performing the Yom Kippur service. Exodus 29:29–30 says, "The holy garments of Aaron shall be for his sons after him, to be anointed in them, and to be consecrated in them. Seven days shall the son that is priest in his stead put them on." This text demonstrated that a priest who had put on the required larger number of garments and who had been anointed on each of the seven days was permitted to serve as High Priest. Leviticus 16:32, however, says, "And the priest who shall be anointed and who shall be consecrated to be priest in his father's stead shall make the atonement." The Baraita interpreted the words, "Who shall be anointed and who shall be consecrated," to mean one who had been anointed and consecrated in whatever way (as long as he had been consecrated, even if some detail of the ceremony had been omitted). The Baraita thus concluded that if the priest had put on the larger number of garments for only one day and had been anointed on each of the seven days, or if he had been anointed for only one day and had put on the larger number of garments for seven days, he would also be permitted to perform the Yom Kippur service.[131]

Reading the words, “He shall make atonement,” in Leviticus 16:33, a Baraita taught that this extended atonement to Canaanite slaves who worked for Jews (as these slaves were obligated in certain commandments and are therefore also warranted atonement).[132]

The Jerusalem Talmud reported that Rav Idi in the name of Rabbi Isaac taught that Leviticus 16:34 includes the words, “As the Lord commanded him,” to teach that the High Priest was required to read Leviticus 16 as part of the Yom Kippur service.[133]

The Jerusalem Talmud reported that Jews wear white on the High Holy Days. Rabbi Hama the son of Rabbi Hanina and Rabbi Hoshaiah disagreed about how to interpret Deuteronomy 4:8, “And what great nation is there, that has statutes and ordinances so righteous as all this law.” One said: “And what great nation is there?” Ordinarily those who know they are on trial wear black, wrap themselves in black, and let their beards grow, since they do not know how their trial will turn out. But that is not how it is with Israel. Rather, on the day of their trial, they wear white, wrap themselves in white, and shave their beards and eat, drink, and rejoice, for they know that God does miracles for them.[134]

Leviticus chapter 17[]

Rabbi Berekiah said in the name of Rabbi Isaac that in the Time to Come, God will make a banquet for God's righteous servants, and whoever had not eaten meat from an animal that died other than through ritual slaughtering (נְבֵלָה, neveilah, prohibited by Leviticus 17:1–4) in this world will have the privilege of enjoying it in the World to Come. This is indicated by Leviticus 7:24, which says, "And the fat of that which dies of itself (נְבֵלָה, neveilah) and the fat of that which is torn by beasts (טְרֵפָה, tereifah), may be used for any other service, but you shall not eat it," so that one might eat it in the Time to Come. (By one's present self-restraint one might merit to partake of the banquet in the Hereafter.) For this reason Moses admonished the Israelites in Leviticus 11:2, "This is the animal that you shall eat."[135]

A Midrash interpreted Psalm 146:7, "The Lord lets loose the prisoners," to read, "The Lord permits the forbidden," and thus to teach that what God forbade in one case, God permitted in another. God forbade the abdominal fat of cattle (in Leviticus 3:3), but permitted it in the case of beasts. God forbade consuming the sciatic nerve in animals (in Genesis 32:33) but permitted it in fowl. God forbade eating meat without ritual slaughter (in Leviticus 17:1–4) but permitted it for fish. Similarly, Rabbi Abba and Rabbi Jonathan in the name of Rabbi Levi taught that God permitted more things than God forbade. For example, God counterbalanced the prohibition of pork (in Leviticus 11:7 and Deuteronomy 14:7–8) by permitting mullet (which some say tastes like pork).[136]

A Tanna taught that the prohibition of the high places stated in Leviticus 17:3–4 took place on the first of Nisan. The Tanna taught that the first of Nisan took ten crowns of distinction by virtue of the ten momentous events that occurred on that day. The first of Nisan was: (1) the first day of the Creation (as reported in Genesis 1:1–5), (2) the first day of the princes' offerings (as reported in Numbers 7:10–17), (3) the first day for the priesthood to make the sacrificial offerings (as reported in Leviticus 9:1–21), (4) the first day for public sacrifice, (5) the first day for the descent of fire from Heaven (as reported in Leviticus 9:24), (6) the first for the priests' eating of sacred food in the sacred area, (7) the first for the dwelling of the Shechinah in Israel (as implied by Exodus 25:8), (8) the first for the Priestly Blessing of Israel (as reported in Leviticus 9:22, employing the blessing prescribed by Numbers 6:22–27), (9) the first for the prohibition of the high places (as stated in Leviticus 17:3–4), and (10) the first of the months of the year (as instructed in Exodus 12:2). Rav Assi of Hozna'ah deduced from the words, "And it came to pass in the first month of the second year, on the first day of the month," in Exodus 40:17 that the Tabernacle was erected on the first of Nisan.[137]

The Gemara interpreted the prohibition on consuming blood in Leviticus 17:10 to apply to the blood of any type of animal or fowl, but not to the blood of eggs, grasshoppers, and fish.[138]

Leviticus chapter 18[]

Rabbi Ḥiyya taught that the words “I am the Lord your God” appear twice, in Leviticus 18:2 and 4, to teach that God was the God who inflicted punishment upon the Generation of the Flood, Sodom, and Egypt, and God is the same God who will inflict punishment on anyone who will act as they did.[139]

Applying the prohibition against following the ways of the Canaanites in Leviticus 18:3, the Sages of the Mishnah prohibited going out with talismans like a locust's egg, a fox's tooth, or a nail from a gallows, but Rabbi Meir allowed it, and the Gemara reported that Abaye and Rava agreed, excepting from the prohibition of Leviticus 18:3 any practice of evident therapeutic value.[140]

Leviticus 18:4 calls on the Israelites to obey God's "statutes" (chukim) and "ordinances" (mishpatim). The Rabbis in a Baraita taught that the "ordinances" (mishpatim) were commandments that logic would have dictated that we follow even had Scripture not commanded them, like the laws concerning idolatry, adultery, bloodshed, robbery, and blasphemy. And "statutes" (chukim) were commandments that the Adversary challenges us to violate as beyond reason, like those relating to shaatnez (in Leviticus 19:19 and Deuteronomy 22:11), halizah (in Deuteronomy 25:5–10), purification of the person with tzaraat (in Leviticus 14), and the scapegoat (in Leviticus 16:7–10). So that people do not think these "ordinances" (mishpatim) to be empty acts, in Leviticus 18:4, God says, "I am the Lord," indicating that the Lord made these statutes, and we have no right to question them.[141]

Rabbi Eleazar ben Azariah taught that people should not say that they do not want to wear a wool-linen mixture (שַׁעַטְנֵז, shatnez, prohibited by Leviticus 19:19 and Deuteronomy 22:11), eat pork (prohibited by Leviticus 11:7 and Deuteronomy 14:7–8), or be intimate with forbidden partners (prohibited by Leviticus 18 and 20), but rather should say that they would love to, but God has decreed that they not do so. For in Leviticus 20:26, God says, "I have separated you from the nations to be mine." So one should separate from transgression and accept the rule of Heaven.[142]

The Gemara cited Leviticus 18:5 for the proposition that, except for a very few circumstances, a person need not obey God's commandments if doing so would cause the person to die. Interpreting what constitutes profanation of God's Name within the meaning of Leviticus 22:32, Rabbi Johanan said in the name of Rabbi Simeon ben Jehozadak that by a majority vote, it was resolved in the attic of the house of Nitzah in Lydda that if a person is directed to transgress a commandment in order to avoid being killed, the person may transgress any commandment of the Torah to stay alive except idolatry, prohibited sexual relations, and murder. With regard to idolatry, the Gemara asked whether one could commit it to save one's life, as it was taught in a Baraita that Rabbi Ishmael said that if a person is directed to engage in idolatry in order to avoid being killed, the person should do so, and stay alive. Rabbi Ishmael taught that we learn this from Leviticus 18:5, "You shall therefore keep my statutes and my judgments, which if a man do, he shall live in them," which means that a person should not die by them. From this, one might think that a person could openly engage in idolatry in order to avoid being killed, but this is not so, as Leviticus 22:32 teaches, "Neither shall you profane My holy Name; but I will be hallowed." When Rav Dimi came from the Land of Israel to Babylonia, he taught that the rule that one may violate any commandment except idolatry, prohibited sexual relations, and murder to stay alive applied only when there is no royal decree forbidding the practice of Judaism. But Rav Dimi taught that if there is such a decree, one must incur martyrdom rather than transgress even a minor precept. When Ravin came, he said in Rabbi Johanan's name that even absent such a decree, one was allowed to violate a commandment to stay alive only in private; but in public one needed to be martyred rather than violate even a minor precept. Rava bar Rav Isaac said in Rav's name that in this context one should choose martyrdom rather than violate a commandment even to change a shoe strap. Rabbi Jacob said in Rabbi Johanan's name that the minimum number of people for an act to be considered public is ten. And the Gemara taught that ten Jews are required for the event to be public, for Leviticus 22:32 says, "I will be hallowed among the children of Israel."[143]

Rabbi Levi taught that the punishment for false weights or measures (discussed at Deuteronomy 25:13–16) was more severe than that for having intimate relations with forbidden relatives (discussed at Leviticus 18:6–20). For in discussing the case of forbidden relatives, Leviticus 18:27 uses the Hebrew word אֵל, eil, for the word "these," whereas in the case of false weights or measures, Deuteronomy 25:16 uses the Hebrew word אֵלֶּה, eileh, for the word "these" (and the additional ה, eh at the end of the word implies additional punishment.) The Gemara taught that one can derive that אֵל, eil, implies rigorous punishment from Ezekiel 17:13, which says, "And the mighty (אֵילֵי, eilei) of the land he took away." The Gemara explained that the punishments for giving false measures are greater than those for having relations with forbidden relatives because for forbidden relatives, repentance is possible (as long as there have not been children), but with false measure, repentance is impossible (as one cannot remedy the sin of robbery by mere repentance; the return of the things robbed must precede it, and in the case of false measures, it is practically impossible to find out all the members of the public who have been defrauded).[144]

The Gemara interpreted Leviticus 18:7 to prohibit a man from lying with his father's wife, whether or not she was his mother, and whether or not the father was still alive.[145]

The Mishnah taught that Leviticus 18:17, in prohibiting "a woman and her daughter," prohibited a man’s daughter, his daughter's daughter, his son's daughter, his wife's daughter, her daughter's daughter, his mother-in-law, the mother of his mother-in-law, and the mother of his father-in-law.[146]