Encephalartos woodii

| Wood's cycad | |

|---|---|

| |

| A large stem of Encephalartos woodii at the Durban Botanic Gardens | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Division: | Cycadophyta |

| Class: | Cycadopsida |

| Order: | Cycadales |

| Family: | Zamiaceae |

| Genus: | Encephalartos |

| Species: | E. woodii

|

| Binomial name | |

| Encephalartos woodii | |

Encephalartos woodii, Wood's cycad, is a rare cycad in the genus Encephalartos, and is endemic to the oNgoye Forest of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. It is one of the rarest plants in the world, being extinct in the wild with all specimens being clones of the type.[2] The specific and common name both honour John Medley Wood, curator of the Durban Botanic Garden and director of the of South Africa, who discovered the plant in 1895.[3]

Description[]

It is palm tree like, and can reach a height of 6 metres (20 ft). The trunk is about 30–50 centimetres (12–20 in) in diameter, thickest at the bottom, and topped by a crown of 50–150 leaves. The leaves are glossy and dark green, 150–250 centimetres (59–98 in) in length, and keeled with 70–150 leaflets, the leaflets falcate (sickle-shaped), 13–15 centimetres (5–6 in) long and 20–30 millimetres (0.8–1 in) broad.[4][5]

E. woodii is dioecious, meaning it has separate male and female plants, however no female plant has ever been discovered. The male strobili are cylindrical, 20–40 centimetres (7.9–16 in) long, exceptionally up to 120 centimetres (47 in), and 15–25 centimetres (6–10 in) in diameter; they are a vivid yellow-orange colour. A single plant may bear from around six to eight simultaneously.[4][5]

Taxonomy[]

Encephalartos woodii was first described by Wood as a variety of E. altensteinii (as E. altensteinii var. bispinna), and raised to the rank of species in 1908 by the English horticulturalist Henry Sander[5] from studying a specimen in his collection, which was apparently one of the basal offsets taken from the original clump.[2] It has been considered that Encephalartos woodii is most closely related to E. natalensis. Some authorities consider E. woodii to not be a true species but rather a mutant E. natalensis or a relic of some other species. Yet others consider this plant to be a natural hybrid between E. natalensis and E. ferox.[4] To determine the relationship between E. natalensis and E. woodii, the RAPD technique was used to generate genetic fingerprints and data analysed using distance methods. Based on RAPD fingerprints, the intraspecific genetic variation among different E. natalensis plants is similar to the interspecific variation between E. natalensis and E. woodii, which confirms the close relationship between E. natalensis and E. woodii.[6]

Distribution and habitat[]

Original distribution[]

The only known wild plants of E. woodii were a cluster of four stems of one plant discovered by Wood in 1895 in a small area of Ngoya Forest,[7] now known by its proper Zulu name of oNgoye, which is in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa.[8] The site where this plant was found was on a steep south-facing slope[2][9] on the fringes of the forest.[9] The annual rainfall at the site ranges between 750–1,000 millimetres (30–39 in), and the climate has hot summers and mild winters.[2]

Removal from natural habitat[]

A basal offset of the main stems was removed and sent to Kew Gardens in 1899.[2] Three basal offsets were collected by Wood's deputy, , in 1903 and planted in the Durban Botanic Gardens.[9] One specimen was received at the National Botanic Gardens of Ireland in Glasnevin in 1905[10] where the register records it as "Encephalartos way of E. Alten[steinii]" costing 1 guinea from Sander & Sons.[11] In a 1907 expedition, Wylie collected two of the larger stems and noted that of the remaining two, one of them (the largest of the four original stems) was badly mutilated and he did not expect it to survive.[9] By 1912 there was only one 3 metres (9.8 ft) tall trunk left in the wild, and in 1916, the Forestry Department arranged to have it removed and sent to the Government Botanist in Pretoria.[9] It is thought that this trunk subsequently died in 1964.[9]

Current distribution[]

These plants are currently distributed in various botanical institutions around the world.[2] Two of the larger trunks that Wylie collected in the 1907 expedition are still to be seen in the Durban Botanic Gardens.[9] A sucker from one of the Durban Botanic Gardens plants was sent to Kirstenbosch near Cape Town, South Africa in 1916 by James Wylie.[9] The plant that was sent to Kew Gardens in 1899 was grown in the Palm House until April 1997 and then moved to the Temperate House where it produced, for the first time, a male cone in September 2004.[12] In the United States; a specimen is housed in the conservatory at Longwood Gardens near Philadelphia, Pennsylvania[13] and three specimens are to be seen at Lotusland in Santa Barbara, California[14] where they were planted in 1979.[15] The specimen at Longwood Gardens was received in 1969 after a request was made to the Durban Botanic Gardens by one of Longwood's former directors, , when he went on a plant exploration voyage to South Africa in the 1960s.[16] The rooted plant was first taken to the Research Department at Longwood where the gardeners nurtured the plant until it was ready to be displayed in the Conservatory.[16] The Longwood specimen produces cones in early winter.[16] In Europe; a specimen is housed in the Netherlands at Hortus Botanicus in Amsterdam[17] and in Orto Botanico di Napoli in Italy,[18] although this specimen may have died. The specimen in Ireland at Glasnevin is said to be "probably the tallest" specimen of E. woodii in Europe.[10]

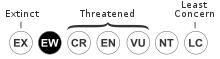

Conservation status[]

Despite numerous excursions in the oNgoye-Mtunzini area, no other specimens of Encephalartos woodii have ever been found. All known specimens of Encephalartos woodii are clones of the only known male plant which was completely removed from the wild. For these reasons, the plant is considered extinct in the wild.[1]

Legislation[]

As is the case with all members of the genus Encephalartos, Encephalartos woodii is protected by both national and international legislation:[4]

In South Africa one requires a permit from Nature Conservation to move, sell, buy, donate, receive, cultivate and sell Endangered Flora and to own adult cycads. On an international level all species and hybrids of Encephalartos are on Appendix I of CITES, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. This means that wild collected material may not be traded and for each and every artificially cultivated Encephalartos plant or piece of a plant or a cone or pollen or seed, being carried over an international border requires a CITES Export Permit issued by the authority of the exporting country, and a CITES Import Permit issued by the authority of the importing country.[4]

Reproduction and propagation[]

Vegetative reproduction[]

Encephalartos woodii reproduces with rapidly growing suckers.[4][5]

Sexual reproduction[]

Unless a female plant is found, E. woodii will never reproduce naturally. This species is known to form fertile hybrids with E. natalensis, and a backcrossing technique can be used: if each offspring is subsequently crossed with E. woodii and the process is then repeated, after several generations, female offspring will be closer to what a female Encephalartos woodii would be like.[4] However, genetic analysis of chloroplast DNA of F1 hybrids between E. woodii and E. natalensis showed that all chloroplasts are inherited from the female E. natalensis,[19] indicating that multigenerational hybrid offspring would have E. natalensis chloroplasts and could never be "pure" E. woodii.

Distribution of hybrids[]

Several hybrids between E. woodii and other species of Encephalartos have been produced including:

- Encephalartos gratus x E. woodii at Lotus Land, California.[14]

- Encephalartos natalensis x E. woodii at Orto botanico di Palermo in Italy, and in various collections in South Africa and the United States.

- Encephalartos transvenosus x E. woodii in collections in South Africa and the United States.

Gallery[]

The bark of the specimen planted in Kirstenbosch botanical garden

Male cone of Encephalartos woodii

Portion of a leaf showing leaflets

The last two stems of Encephalartos woodii at oNgoye in the early 1900s

One of the original stems at the Durban Botanic Gardens

Original stem at Durban Botanic Gardens, 2010

Offshoots (suckers) showing roots developing on the largest one

A female E. natalensis x woodii with cones

Encephalartos natalensis x E. woodii hybrid at Orto botanico di Palermo

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Donaldson, J.S. (2003). "'Encephalartos woodii'". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2003. Retrieved 16 November 2006.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Jones, D.L. (1993). Cycads of the World: Ancient Plants in Today's Landscape. ISBN 0-7301-0338-2.

- ^ "Encephalartos woodii". Cycads. Kew Botanical Gardens. Archived from the original on 20 June 2008. Retrieved 16 November 2006.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Notten, A. (May 2002). "Encephalartos woodii Sander". Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden and South African National Biodiversity Institute. Retrieved 16 November 2006.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Hill, K. (2004). "Encephalartos woodii". Royal Botanic Gardens Sydney. Retrieved 1 December 2006.

- ^ Viljoen, C.D. & van Staden, J. The genetic relationship between Encephalartos natalensis and E. woodii determined using RAPD fingerprinting. South African Journal of Botany Volume 72, Issue 4, November 2006, Pages 642-645

- ^ Neels Esterhuyse; Jutta von Breitenbach; Hermien Söhnge (2001). Reneé Ferreira (ed.). Remarkable Trees of South Africa. Briza Publications. p. 51. ISBN 1-875093-28-1.

- ^ Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife/. Retrieved 7 September 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Encephalartos woodii Sander: http://www.plantzafrica.com/plantefg/encephwoodii.htm, retrieved 7 September 2010

- ^ Jump up to: a b Czech Cycads: Cycads in Ireland: http://www.cykasy.cz/English/Cycads_in_Ireland.html, retrieved 20 September 2010.

- ^ National Botanical Gardens, Glasnevin: Conservation News: http://www.botanicgardens.ie/conserve/consnews.htm Archived 9 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 20 September 2010.

- ^ http://www.kew.org/plants/cycads/encephalartos_woodii.html Archived 30 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 7 September 2010.

- ^ Rare Plants in Pennsylvania. Wood's Cycad. Encephalartos woodii: "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 14 August 2010. Retrieved 14 September 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link), retrieved 14 September 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lotusland Plant Collection: http://www.lotusland.org/explore-garden/gardens/cycad-garden/, retrieved 14 September 2010.

- ^ Compiled List of Cycad Gardens: http://www.plantapalm.com/vce/cycadsof/cycadgardens.htm Archived 17 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 14 September 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c The King of Our Conservatory: http://www.facebook.com/note.php?note_id=296456165465, retrieved 14 September 2010.

- ^ Dutch Botanic Gardens Collections Foundation: http://www.nationale-plantencollectie.nl/UK/collectiehouders/Cycads-gen.htm[permanent dead link], retrieved 14 September 2010.

- ^ Los Gatos Plants - UK Cycad Resource: "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 1 July 2012. Retrieved 14 September 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link), retrieved 14 September 2010.

- ^ Cafasso, D. et al. (2001). Maternal inheritance of plastids in Encephalartos Lehm. (Zamiaceae, Cycadales) Genome. 2001 (2):239-41.

External links[]

- IUCN Red List extinct in the wild species

- Encephalartos

- Endemic flora of South Africa

- Trees of South Africa

- Extinct biota of Africa

- Plants extinct in the wild

- KwaZulu-Natal

- Critically endangered flora of Africa