Energy subsidy

Energy subsidies are measures that keep prices for customers below market levels, or for suppliers above market levels, or reduce costs for customers and suppliers.[1] Energy subsidies may be direct cash transfers to suppliers, customers, or related bodies, as well as indirect support mechanisms, such as tax exemptions and rebates, price controls, trade restrictions, and limits on market access.

Eliminating fossil fuel subsidies would greatly reduce global carbon emissions[2][3][4] and would reduce the health risks of air pollution.[5] Direct global fossil fuel subsidies reached $319 billion in 2017, and $5.2 trillion when indirect costs such as air pollution are priced in.[6] Ending these can cause a 28% reduction in global carbon emissions and a 46% reduction in air pollution deaths.[7] According to Greenpeace worldwide damages from fossil fuel air pollution amount to $2.9 trillion annually or $8 billion a day.[8]

Overview[]

Main arguments for energy subsidies are:

- Security of supply – subsidies are used to ensure adequate domestic supply by supporting indigenous fuel production in order to reduce import dependency, or supporting overseas activities of national energy companies.[citation needed]

- Environmental improvement – subsidies are used to reduce pollution, including different emissions, and to fulfill international obligations (e.g. Kyoto Protocol).[citation needed]

- Economic benefits – subsidies in the form of reduced prices are used to stimulate particular economic sectors or segments of the population, e.g. alleviating poverty and increasing access to energy in developing countries.[citation needed]

- Employment and social benefits – subsidies are used to maintain employment, especially in periods of economic transition.[9][better source needed]

Main arguments against energy subsidies are:

- Some energy subsidies counter the goal of sustainable development, as they may lead to higher consumption and waste, exacerbating the harmful effects of energy use on the environment, create a heavy burden on government finances and weaken the potential for economies to grow, undermine private and public investment in the energy sector.[10] Also, most benefits from fossil fuel subsidies in developing countries go to the richest 20% of households.[11]

- Impede the expansion of distribution networks and the development of more environmentally benign energy technologies, and do not always help the people that need them most.[10]

- The study conducted by the World Bank finds that subsidies to the large commercial businesses that dominate the energy sector are not justified. However, under some circumstances it is reasonable to use subsidies to promote access to energy for the poorest households in developing countries. Energy subsidies should encourage access to the modern energy sources, not to cover operating costs of companies.[12] The study conducted by the World Resources Institute finds that energy subsidies often go to capital intensive projects at the expense of smaller or distributed alternatives.[13]

Types of energy subsidies are:

- Direct financial transfers – grants to suppliers; grants to customers; low-interest or preferential loans to suppliers.

- Preferential tax treatments – rebates or exemption on royalties, duties, supplier levies and tariffs; tax credit; accelerated depreciation allowances on energy supply equipment.

- Trade restrictions – quota, technical restrictions and trade embargoes.

- Energy-related services provided by government at less than full cost – direct investment in energy infrastructure; public research and development.

- Regulation of the energy sector – demand guarantees and mandated deployment rates; price controls; market-access restrictions; preferential planning consent and controls over access to resources.

- Failure to impose external costs – environmental externality costs; energy security risks and price volatility costs.[10]

- Depletion Allowance – allows a deduction from gross income of up to ~27% for the depletion of exhaustible resources (oil, gas, minerals).

Overall, energy subsidies require coordination and integrated implementation, especially in light of globalization and increased interconnectedness of energy policies, thus their regulation at the World Trade Organization is often seen as necessary.[14][15]

Impact of fossil fuel subsidies[]

The degree and impact of fossil fuel subsidies is extensively studied. Because fossil fuels are a leading contributor to climate change through greenhouse gases, fossil fuel subsidies increase emissions and exacerbate climate change. The OECD created an inventory in 2015 of subsidies for the extraction, refining, or combustion of fossil fuels among the OECD and large emerging economies. This inventory identified an overall value of $160 to $200 billion per year between 2010 and 2014.[16][17] Meanwhile, the International Energy Agency has estimated global fossil fuel subsidies as ranging from $300 to $600 billion per year between 2008 and 2015.[18]

According to the International Energy Agency, the elimination of fossil fuel subsidies worldwide would be one of the most effective ways of reducing greenhouse gases and battling global warming.[3] Along with this, elimination of these subsidies was welcomed by the G20 nations as a way reduce expenditures during the recession during the 2009 Pittsburgh Summit.[19] In May 2016, the G7 nations set for the first time a deadline for ending most fossil fuel subsidies; saying government support for coal, oil and gas should end by 2025.[20] According to a 2019 report by the Overseas Development Institute, the G20 governments still provide billions of dollars of support for the production and consumption of fossil fuels, spending at least $63.9 billion per year on coal alone.[21] At the time of the 2020 G20 Summit, a policy brief found, that in general, governments have not enacted policies that sufficiently drew down fossil fuel subsidies since the 2009 Pittsburgh Summit.[22]

According to the OECD, subsidies to nuclear power contribute to unique environmental and safety issues, related mostly to the risk of high-level environmental damage, although nuclear power contributes positively to the environment in the areas of air pollution and climate change.[23][better source needed] According to Fatih Birol, Chief Economist at the International Energy Agency, without a phasing out of fossil fuel subsidies, countries will not reach their climate targets.[24]

In 2011, IEA chief economist Fatih Birol said the current $409 billion equivalent of fossil fuel subsidies (in non-OECD countries) are encouraging a wasteful use of energy, and that the cuts in subsidies is the biggest policy item that would help renewable energies get more market share and reduce CO2 emissions.[25]

Environmental cost[]

Global fossil fuel subsidies reached $319 billion in 2017, although this number rises to $5.2 trillion (equivalent to 6.3% of world economy), when the economic value of environmental externalities such as air pollution are priced in.[6] When measured this way, ending these subsidies can cause a 28% reduction in global carbon emissions and a 46% reduction in deaths due to fossil fuel air pollution.[7] Total global air pollution deaths reach 7 million annually.[6] Using this definition, "China was the biggest subsidizer in 2013 ($1.8 trillion), followed by the United States ($0.6 trillion), and Russia, the European Union, and India (each with about $0.3 trillion)."[2][clarification needed]

IEA position on subsidies[]

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA) phasing out fossil fuel subsidies would benefit energy markets, climate change mitigation and government budgets.[26]

Subsidies by country[]

This article's factual accuracy may be compromised due to out-of-date information. (September 2018) |

The International Energy Agency estimates that governments subsidised fossil fuels by US $548 billion in 2013.[27] Ten countries accounted for almost three-quarters of this figure.[28] At their meeting in September 2009 the G-20 countries committed to "rationalize and phase out over the medium term inefficient fossil fuel subsidies that encourage wasteful consumption".[29] The 2010s have seen many countries reducing energy subsidies, for instance in July 2014 Ghana abolished all diesel and gasoline subsidies, whilst in the same month Egypt raised diesel prices 63% as part of a raft of reforms intended to remove subsidies within 5 years.[30]

Canada[]

Fossil fuel subsidies[]

The Canadian federal government offers subsidies for fossil fuel exploration and production and Export Development Canada regularly provides financing to oil and gas companies. A 2018 report from the Overseas Development Institute, a UK-based think tank, found that Canada spent a greater proportion of its GDP on fiscal support to oil and gas production in 2015 and 2016 than any other G7 country.[31]

In 2015 and 2016, the largest federal subsidies for fossil fuel exploration and production were the Canadian Exploration Expense (CEE), the Canadian Development Expense (CDE), and the Atlantic Investment Tax Credit (AITC).[32] In these years Canada paid a yearly average of $1.018 billion CAD to oil and gas companies through the CDE, $148 million CAD through the CEE, and $127 million through the AITC. In 2017, subsidies to oil and gas through the AITC were phased out.[32] Also in 2017, the federal government reformed the CEE so that exploration expenses may only be deducted through it if the exploration is unsuccessful. Otherwise, these expenses must be deducted through the CDE, which is deductible at 30% rather than 100%.[33]

In December 2018, in response to low Canadian oil prices, the federal government announced $1.6 billion in financial support for the oil and gas sector: $1 billion in loans to oil and gas exporters from Export Development Canada, $500 million in financing for “higher risk” oil and gas companies from the Business Development Bank of Canada, $50 million through Natural Resources Canada’s Clean Growth Program, and $100 million through Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada’s Strategic Innovation Fund. Minister of Natural Resources Amarjeet Sohi said that this financing is “not a subsidy for fossil fuels”, adding that “These are commercial loans, made available on commercial terms. We have committed to phasing out inefficient fossil fuel subsidies by 2025, and we stand by that commitment".[34] In 2016, Canada committed to “phase out inefficient fossil fuel subsidies by 2025” in line with commitments made with G20 and G7 countries,[35] although a 2017 report from the Office of the Auditor-General found that little work had been done to define this goal and establish a timeline for achieving it.[36] Reducing subsidies to fossil fuels was an explicit part of the Liberal Party's platform in the 2015 federal election.[37]

The largest provincial fossil fuel subsidies are paid by Alberta and British Columbia. Alberta spent a yearly average of $1.161 billion CAD on Crown Royalty Reductions for oil and gas from 2013 to 2015.[32] And British Columbia paid a yearly average of $271 million CAD to gas companies through the Deep Drilling Credit.[32]

Canadian provincial governments also offer subsidies for the consumption of fossil fuels. For example, Saskatchewan offers a fuel tax exemption for farmers and a sales tax exemption for natural gas used for heating.[38]

A 2018 report from the Overseas Development Institute was critical of Canada's reporting and transparency practices around its fossil fuel subsidies. Canada does not publish specific reports on its fiscal support for fossil fuels, and when Canada’s Office of the Auditor-General attempted an audit of Canadian fossil fuel subsidies in 2017, they found much of the data they needed was not provided by Finance Canada. Export Development Canada reports on their transactions related to fossil fuel projects, but do not provide data on exact amounts or the stage of project development.[11]

Iran[]

Contrary to the subsidy reform plan's objectives, under president Rouhani the volume of Iranian subsidies given to its citizens on fossil fuel increased 42.2% in 2019 and equals 15.3% of Iran’s GDP and 16% of total global energy subsidies. This has made Iran the world's largest subsidizer of energy prices.[39] This situation is leading to highly wasteful consumption patterns, large budget deficits, price distortions in its entire economy, pollution and very lucrative (multi-billion dollars) contraband (because of price differentials) with neighbouring countries each year by rogue elements within the Iranian government supporting the status-quo.[40][41]

Russia[]

Russia is one of the world’s energy powerhouses. It holds the world’s largest natural gas reserves (27% of total), the second-largest coal reserves, and the eighth-largest oil reserves.[42] Russia is the world's third-largest energy subsidizer as of 2015.[43] The country subsidizes electricity and natural gas as well as oil extraction. Approximately 60% of the subsidies go to natural gas, with the remainder spent on electricity (including under-pricing of gas delivered to power stations).[42] For oil extraction the government gives tax exemptions and duty reductions amounting to about 22 billion dollars a year. Some of the tax exemptions and duty reductions also apply to natural gas extraction, though the majority is allocated for oil.[44] The large subsidies of Russia are costly and it is recommended in order to help the economy that Russia lowers its domestic subsidies.[45] However, the potential elimination of energy subsidies in Russia carries the risk of social unrest that makes Russian authorities reluctant to remove them.[46]

Turkey[]

United Kingdom[]

The government says that the 5% value added tax (VAT) rate on natural gas for home heating is not a subsidy, but some environmental groups disagree[58] and say that it should be increased to the standard 20% with the extra revenue ringfenced for poor people.[59]

United States[]

This article needs to be updated. (April 2021) |

Energy subsidies are government payments that keep the price of energy lower than market rate for consumers or higher than market rate for producers. These subsidies are part of the energy policy of the United States.

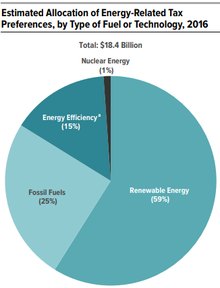

According to Congressional Budget Office testimony in 2016, an estimated $10.9 billion in tax preferences was directed toward renewable energy, $4.6 billion went to fossil fuels, and $2.7 billion went to energy efficiency or electricity transmission.[60]

According to a 2015 estimate by the Obama administration, the US oil industry benefited from subsidies of about $4.6 billion per year.[61] A 2017 study by researchers at Stockholm Environment Institute published in the journal Nature Energy estimated that "tax preferences and other subsidies push nearly half of new, yet-to-be-developed oil investments into profitability, potentially increasing US oil production by 17 billion barrels over the next few decades."[62]Venezuela[]

This section needs to be updated. (July 2021) |

In Venezuela, energy subsidies were equivalent to about 8.9 percent of the country's GDP in 2012. Fuel subsidies were 7.1 percent while electricity subsidies were 1.8 percent. In order to fund this the government used about 85 percent of its tax revenue on these subsidies. It is estimated the subsidies have caused Venezuela to consume 20 percent more energy than without them.[63] The fuel subsidies are given more heavily to the richest part of the population who are consuming the most energy.[64] The fuel subsidies maintained a cost of about $0.01 US for a liter of gasoline at the pump since 1996 until president Nicolas Maduro reduced the national subsidy in 2016 to make it roughly $0.60 US per liter (The local currency is Bolivar and the price per liter of gas is 6 Bolivars).[65] Fuel consumption has increased overall since the 1996 policy began even though the production of oil has fallen more than 350,000 barrels a day since 2008 under that policy.[66] PDVSA, the Venezuelan state oil company, has been losing money on these domestic transactions since the enactment of these policies.[67] These losses can also be attributed to the 2005 Petrocaribe agreement, under which Venezuela sells many surrounding countries petroleum at a reduced or preferable price; essentially a subsidy by Venezuela for countries that are a part of the agreement.[68] The subsidizing of fossil fuels and consequent low cost of fuel at the pump has caused the creation of a large black market. Criminal groups smuggle fuel out of Venezuela to adjacent nations (mainly Colombia). This is due to the large profits that can be gained by this act, as fuel is much more expensive in Colombia than in Venezuela. Despite the fact that this issue is already well known in Venezuela, and insecurity in the region continues to rise, the state has not yet lowered or eliminated these fossil fuel subsidies.[69][70][71]

European Union[]

This section needs to be updated. (November 2019) |

In February 2011 and January 2012 the UK Energy Fair group, supported by other organisations and environmentalists, lodged formal complaints with the European Union's Directorate General for Competition, alleging that the Government was providing unlawful state aid in the form of subsidies for nuclear power industry, in breach of European Union competition law.[72][73]

One of the largest subsidies is the cap on liabilities for nuclear accidents which the nuclear power industry has negotiated with governments. “Like car drivers, the operators of nuclear plants should be properly insured,” said Gerry Wolff, coordinator of the Energy Fair group. The group calculates that, "if nuclear operators were fully insured against the cost of nuclear disasters like those at Chernobyl and Fukushima, the price of nuclear electricity would rise by at least €0.14 per kWh and perhaps as much as €2.36, depending on assumptions made".[74] According to the most recent statistics, subsidies for fossil fuels in Europe are exclusively allocated to coal (€10 billion) and natural gas (€6 billion). Oil products do not receive any subsidies.[75]

See also[]

- Corporate welfare

- Building-integrated photovoltaics

- Government subsidies

- Feed-in tariff

- Gasoline subsidies

- Renewable Energy Certificates

- Renewable energy commercialization

- Renewable energy payments

- Stranded assets

- Financial incentives for photovoltaics

References[]

- ^ OECD, 1998

- ^ Jump up to: a b Coady, David; Parry, Ian; Sears, Louis; Shang, Baoping (March 2017). "How Large Are Global Fossil Fuel Subsidies?". World Development. 91: 11–27. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.10.004.

- ^ Jump up to: a b John Schwartz (December 5, 2015). "On Tether to Fossil Fuels, Nations Speak With Money". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 6, 2015. Retrieved December 5, 2015.

...the elimination of subsidies as one of the most effective strategies for reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

- ^ Ross, Michael L.; Hazlett, Chad; Mahdavi, Paasha (January 2017). "Global progress and backsliding on gasoline taxes and subsidies". Nature Energy. 2 (1): 16201. Bibcode:2017NatEn...216201R. doi:10.1038/nenergy.2016.201.

- ^ "Local Environmental Externalities due to Energy Price Subsidies: A Focus on Air Pollution and Health" (PDF). World Bank.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Watts N, Amann M, Arnell N, Ayeb-Karlsson S, Belesova K, Boykoff M; et al. (2019). "The 2019 report of The Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: ensuring that the health of a child born today is not defined by a changing climate". Lancet. 394 (10211): 1836–1878. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32596-6. PMID 31733928.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Conceição et al. (2020). Human Development Report 2020 The Next Frontier: Human Development and the Anthropocene (PDF) (Report). United Nations Development Programme. p. 10. Retrieved January 9, 2021.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- ^ "Fossil Fuel Air Pollution Costs The World US$8 Billion Every Day". Green Queen. February 12, 2020. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- ^ "Energy subsidies in the European Union: A brief overview. Technical report No 1/2004" (PDF). European Environmental Agency. 2004. Archived from the original on March 14, 2012. Retrieved April 11, 2012. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Jump up to: a b c United Nations Environment Programme, Division of Technology, Industry and Economics. (2002). Reforming energy subsidies (PDF). IEA/UNEP. ISBN 978-92-807-2208-6. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 21, 2007. Retrieved March 9, 2008.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Whitley, Shelagh. "Time to change the game: Fossil fuel subsidies and climate". Overseas Development Institute. Archived from the original on January 3, 2014. Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- ^ Douglas F. Barnes; Jonathan Halpern (2000). "The role of energy subsidies" (PDF). Energy and Development Report: 60–66. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 16, 2008. Retrieved March 9, 2008.

- ^ Jonathan Pershing; Jim Mackenzie (March 2004). "Removing Subsidies. Leveling the Playing Field for Renewable Energy Technologies. Thematic Background Paper" (PDF). Secretariat of the International Conference for Renewable Energies. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 6, 2004. Retrieved March 9, 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Farah, Paolo Davide; Cima, Elena (2015). "World Trade Organization, Renewable Energy Subsidies and the Case of Feed-In Tariffs: Time for Reform Toward Sustainable Development?". Georgetown International Environmental Law Review (GIELR). 27 (1). SSRN 2704398. and Farah, Paolo Davide; Cima, Elena (December 15, 2015). "WTO and Renewable Energy: Lessons from the Case Law". 49 JOURNAL OF WORLD TRADE 6, Kluwer Law International. SSRN 2704453.

- ^ Farah, Paolo Davide and Cima, Elena, WTO and Renewable Energy: Lessons from the Case Law (December 15, 2015). 49 JOURNAL OF WORLD TRADE 6, Kluwer Law International, ISSN 1011-6702, December 2015, pp. 1103 – 1116. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2704453

- ^ "OECD Companion to the Inventory of Support Measures for Fossil Fuels 2015 | READ online". OECD iLibrary. Retrieved November 23, 2018.

- ^ "Explainer: The challenge of defining fossil fuel subsidies | Carbon Brief". Carbon Brief. June 12, 2017. Retrieved November 23, 2018.

- ^ "Estimates for global fossil-fuel consumption subsidies". IEA. Retrieved June 5, 2019.

- ^ Blondeel, Mathieu; Colgan, Jeff; Van de Graaf, Thijs (October 9, 2019). "What Drives Norm Success? Evidence from Anti–Fossil Fuel Campaigns". Global Environmental Politics. 19 (4): 63–84. doi:10.1162/glep_a_00528. S2CID 203912396. Retrieved December 6, 2020.

- ^ Mathiesen, Karl (May 27, 2016). "G7 nations pledge to end fossil fuel subsidies by 2025". The Guardian. Archived from the original on June 6, 2016. Retrieved June 7, 2016.

- ^ "G20 coal subsidies: tracking government support to a fading industry". ODI. June 2019. Retrieved November 22, 2019.

- ^ {{Cite web|url=https://www.bakerinstitute.org/research/fossil-fuel-subsidy-reform-pittsburgh-g20-lost-decade |title=Fuel Subsidy Reform Since Pittsburgh G20: A Lost Decade? |date=October 2020 |website=Baker Institute's Center for Energy Studies |language=en |access-date=2021-07-02}

- ^ "Forthcoming, Draft synthesis report on environmentally harmful subsidies, SG/SD(2004)3". OECD. March 16, 2004. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Fossil fuel subsidies are “public enemy number one” – IEA Chief Archived 2013-02-11 at the Wayback Machine EWEA 04 Feb 2013

- ^ "Renewable Energy Being Held Back by Fossil Fuel Subsidies – IEA". Oilprice.com. November 1, 2011. Archived from the original on November 3, 2011.

- ^ "Energy subsidies – Topics". IEA. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- ^ "Energy Subsidies". International Energy Agency. 2015. Archived from the original on April 26, 2015. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ^ van der Hoeven, Maria (January 27, 2015). "Opportunity to act: making smart decisions in a time of low oil prices" (PDF). p. 8. Archived from the original (pdf) on April 3, 2015. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ^ "Joint report by IEA, OPEC, OECD and World Bank on fossil-fuel and other energy subsidies: An update of the G20 Pittsburgh and Toronto Commitments" (PDF). International Energy Agency. 2011. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 10, 2014. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ^ "Recent Developments in Energy Subsidies" (PDF). International Energy Agency. 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 26, 2015. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ^ "G7 fossil fuel subsidy scorecard" (PDF). June 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Unpacking Canada's Fossil Fuel Subsidies – Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ's)". Retrieved May 19, 2019.

- ^ "New rules affecting treatment of oil and gas resource expenses". nortonrosefulbright.com. Retrieved May 19, 2019.

- ^ News, Carl Meyer in; Energy; December 18th 2018, Politics | (December 18, 2018). "Sohi announces $1.6 billion to help Alberta oilpatch". National Observer. Retrieved May 19, 2019.

- ^ Government of Canada, Department of Finance (June 14, 2018). "Canada and Argentina to Undergo Peer Reviews of Inefficient Fossil Fuel Subsidies". fin.gc.ca. Retrieved May 19, 2019.

- ^ Government of Canada, Office of the Auditor General of Canada (May 16, 2017). "Report 7—Fossil Fuel Subsidies". oag-bvg.gc.ca. Retrieved May 19, 2019.

- ^ "Real Change: A New Plan for Canada's Environment and Economy" (PDF).

- ^ "Meeting Canada's Subsidy Phase-Out Goal: What it means in Saskatchewan". IISD. August 29, 2016. Retrieved May 19, 2019.

- ^ "Iran: Largest Fuel Subsidizer in 2018". Financial Tribune. July 16, 2019.

- ^ "Blind subsidy system costing economy greatly". March 5, 2019.

- ^ "Why Fuel is Smuggled Out of Iran and Why No One Stops It".

- ^ Jump up to: a b Grant, Dansie; Marc, Lanteigne; Overland, Indra (February 1, 2010). "Reducing Energy Subsidies in China, India and Russia: Dilemmas for Decision Makers". Sustainability. 2 (2): 475–493. doi:10.3390/su2020475. Archived from the original on April 11, 2018.

- ^ "WEO - Energy Subsidies". worldenergyoutlook.org. Archived from the original on August 15, 2017. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- ^ Ogarenko, Luliia (November 2015). "G20 subsidies to oil, gas and coal production: Russia" (PDF). IISD. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 11, 2017.

- ^ "June: IEA releases review of Russian energy policies". iea.org. Archived from the original on March 21, 2017. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- ^ Indra Overland (2010) ‘Subsidies for Fossil Fuels and Climate Change: A Comparative Perspective’, International Journal of Environmental Studies, Vol. 67, No. 3, pp. 203-217. "Subsidies for fossil fuels and climate change: A comparative perspective". Archived from the original on February 12, 2018. Retrieved February 11, 2018.

- ^ Acar, Sevil; Challe, Sarah; Christopoulos, Stamatios; Christo, Giovanna (2018). "Fossil fuel subsidies as a lose-lose: Fiscal and environmental burdens in Turkey" (PDF). New Perspectives on Turkey. 58: 93–124. doi:10.1017/npt.2018.7. S2CID 149594404. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 27, 2020.

- ^ Climate Policy Factbook (Report). BloombergNEF. July 20, 2021. p. 29.

- ^ Climate Policy Factbook (Report). BloombergNEF. July 20, 2021. p. 32.

- ^ "Analysis: New Turkish energy minister bullish for coal – but lira weakness limits market". S & P Global. July 12, 2018. Archived from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- ^ "Court says 'environment report necessary' for planned coal mine in western Turkey". Demirören News Agency. August 10, 2018. Archived from the original on October 16, 2018. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- ^ "Fossil Fuel Support – TUR" Archived 31 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine, OECD, accessed August 2018.

- ^ "Taxing Energy Use 2019 : Using Taxes for Climate Action". OECD. Archived from the original on January 12, 2021. Retrieved April 13, 2020.

- ^ "Kapasite mekanizmasıyla 2019'da 40 santrale 1.6 milyar lira ödendi" (in Turkish). Enerji Günlüğü. February 6, 2020. Archived from the original on January 12, 2021. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- ^ "Taxing Energy Use 2019: Country Note – Turkey" (PDF). OECD. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 24, 2020. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ^ Leggett, Theo (January 21, 2018). "Reality Check: Are diesel cars always the most harmful?". BBC News. Archived from the original on July 16, 2020. Retrieved April 13, 2020.

- ^ DifiglioGürayMerdan (2020), p. 202.

- ^ editor, Damian Carrington Environment (January 23, 2019). "UK has biggest fossil fuel subsidies in the EU, finds commission". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved January 10, 2021.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- ^ "Green Alliance (Press release) End £2bn VAT subsidy on gas". www.green-alliance.org.uk. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ Dinan, Terry (March 29, 2017). "CBO Testimony, Federal support for developing, producing, and using fuels and energy technologies" (PDF). cbo.gov/. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 16, 2017. Retrieved November 7, 2017.

- ^ McDonnell, Tim (October 2, 2017). "Analysis | Forget the Paris agreement. The real solution to climate change is in the U.S. tax code". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on October 2, 2017. Retrieved October 3, 2017.

- ^ Erickson, Peter; Down, Adrian; Lazarus, Michael; Koplow, Doug (2017). "Effect of subsidies to fossil fuel companies on United States crude oil production". Nature Energy. 2 (11): 891–898. Bibcode:2017NatEn...2..891E. doi:10.1038/s41560-017-0009-8. S2CID 158727175.

- ^ Troncoso, Karin; Soares da Silva, Agnes (August 1, 2017). "LPG fuel subsidies in Latin America and the use of solid fuels to cook". Energy Policy. 107: 188–196. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2017.04.046.

- ^ "The wild frontier". The Economist. August 16, 2014. Archived from the original on March 24, 2018. Retrieved May 3, 2018.

- ^ Brodzinsky, Sibylla (February 17, 2016). "Venezuela president raises fuel price by 6,000% and devalues bolivar to tackle crisis". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on August 6, 2017. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- ^ Monaldi, Francisco (September 2015). "THE IMPACT OF THE DECLINE IN OIL PRICES ON THE ECONOMICS, POLITICS AND OIL INDUSTRY OF VENEZUELA". Columbia SIPA: Center on Global Energy Policy – via Columbia University.

- ^ Di Bella, Gabriella (February 2015). "Energy Subsidies in Latin America and the Caribbean: Stocktaking and Policy Challenges". IMF Working Paper – via IADB.

- ^ Robalino-López, Andrés; Mena-Nieto, Ángel; García-Ramos, José-Enrique; Golpe, Antonio A. (January 1, 2015). "Studying the relationship between economic growth, CO2 emissions, and the environmental Kuznets curve in Venezuela (1980–2025)" (PDF). Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 41: 602–614. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2014.08.081. hdl:10272/9314.

- ^ "Episode 2, Caribbean with Simon Reeve - BBC Two". BBC. Archived from the original on February 27, 2018. Retrieved May 3, 2018.

- ^ González, Ángel (April 12, 2013). "Almost-Free Gas Comes at a High Cost". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on December 7, 2017. Retrieved May 3, 2018 – via wsj.com.

- ^ Vyas, Kejal (June 9, 2014). "Venezuela Pays Price for Smuggling". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on January 17, 2018. Retrieved May 3, 2018 – via wsj.com.

- ^ Legal bid to halt nuclear construction[permanent dead link], Energy Fair, published 2011-11-07, accessed 2012-01-20

- ^ UK 'subsidising nuclear power unlawfully' Archived 2012-01-20 at the Wayback Machine BBC, published 2012-01-20, accessed 2012-01-20

- ^ "Complaint about nuclear subsidies may prevent new reactor builds". Energy and Environmental Management. January 24, 2012. Archived from the original on May 26, 2013. Retrieved January 25, 2012.

- ^ 'Subsidies and costs of EU energy' Archived 2016-03-28 at the Wayback Machine European Commission, published 2014, accessed 2017-06-20

Bibliography[]

- Difiglio, Prof. Carmine; Güray, Bora Şekip; Merdan, Ersin (November 2020). Turkey Energy Outlook. iicec.sabanciuniv.edu (Report). Sabanci University Istanbul International Center for Energy and Climate (IICEC). ISBN 978-605-70031-9-5.

External links[]

- Energy economics

- Renewable energy commercialization

- Subsidies