Environmental enteropathy

| Environmental enteropathy | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Tropical enteropathy or Environmental enteric dysfunction |

| |

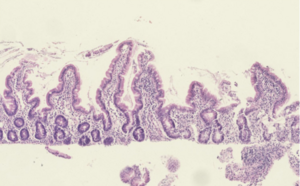

| Histological evidence of enteropathy (inflammatory infiltrate, villus blunting) seen in this intestinal biopsy from a child with malnutrition.[1] | |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology |

| Symptoms | Asymptomatic (most common), altered stool consistency, increased stool frequency, weight loss |

| Complications | Malnutrition, malabsorption, growth stunting, developmental delay, impaired response to oral vaccines |

| Duration | Chronic |

| Causes | Unsanitary food and water sources, fecal-oral contamination, chronic enteric infections, mucosal inflammation |

| Diagnostic method | Intestinal biopsy (gold standard), abnormal sugar absorption test, clinical (significantly more common) |

| Differential diagnosis | Tropical sprue |

| Prevention | Sanitation |

Environmental enteropathy (EE or tropical enteropathy or environmental enteric dysfunction) is a disorder of chronic intestinal inflammation.[2][3][1] EE is most common amongst children living in low-resource settings.[2][3][1] Acute symptoms are typically minimal or absent.[3] EE can lead to malnutrition, anemia (iron-deficiency anemia and anemia of chronic inflammation),[2] growth stunting, impaired brain development,[4][5][6] and impaired response to oral vaccinations.[7][8]

The cause of EE is multifactorial. Overall, exposure to contaminated food and water leads to a generalized state of intestinal inflammation.[2][3][1] The inflammatory response results in multiple pathological changes to the gastrointestinal tract: Smaller villi, larger crypts (called crypt hyperplasia), increased permeability, and inflammatory cell build-up within the intestines.[3][1][9] These changes result in poor absorption of food, vitamins and minerals.

Standardized, clinically practical diagnostic criteria do not exist. The most accurate diagnostic test is intestinal biopsy. However, this test is invasive and unnecessary for most patients.[2]

Prevention is the strongest and most reliable option for preventing EE and its effects. Therefore, prevention and treatment of EE are often discussed together.[9][10][11]

Signs and symptoms[]

Environmental enteropathy is believed to result in chronic malnutrition and subsequent growth stunting (low height-for-age measurement) as well as other child development deficits.[citation needed]

Short-term[]

EE is rarely symptomatic and is considered a subclinical condition.[2][1][3] However, adults may have mild symptoms or malabsorption such as altered stool consistency, increased stool frequency and weight loss.[citation needed]

Long-term[]

- Malnutrition [2][3]

- EE causes malnutrition by way of both malabsorption and nutritional deficiencies.

- Growth and physical development [9]

- The first two years (and the prior 9 months of fetal life) are critical for linear growth. Stunting is an easy to measure symptom of these child development deficits.

- Neurocognitive (brain development) [5][6]

- Effect on oral vaccination [8][12]

- Many oral vaccines, both live and non-living, have proven to be less immunogenic or less protective when administered to infants, children or adults living in low socioeconomic conditions in developing countries than they are when used in industrialized countries. Widespread EE is hypothesized to be a contributing cause for this observation.

Causes[]

The development of EE is multifactorial, but predominantly associated with chronic exposure to contaminated food and water. This is especially true in environments where widespread open defecation and lack of sanitation are common.[2][3][1]

Mechanism[]

Long-term exposure to environmental pathogens leads to a generalized state of intestinal inflammation. Chronic inflammation leads to both functional and structural changes which alter gut permeability and ability of the intestine to absorb nutrients.[2][3][1]

Specifically, structural changes within the intestine include smaller villi, larger crypts (called crypt hyperplasia), increased permeability, and inflammatory cell build-up within the intestines. These changes result in poor absorption of food, vitamins and minerals – or "modest malabsorption".[2][3][1]

Diagnosis[]

The current gold standard diagnostic test for EE is intestinal biopsy and histological analysis. Histological changes observed include:[1]

- Villous blunting

- Crypt hypertrophy

- Villous fusion

- Mucosal inflammation

However, this procedure is considered too invasive, complex and expensive to be implemented as standard of care.[2] As a result, there are various research efforts underway to identify biomarkers associated with EE, which could serve as less invasive, yet representative, tools to screen for and identify EE from stool samples.[2]

In an effort to identify simple, accurate diagnostic tests for EE, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF) has established an EE biomarkers consortium as part of their Global Grand Challenges initiative (specifically, the Discover Biomarkers of Gut Function challenge).[2]

So far, various biomarkers have been selected and studied based on the current understanding of EE pathophysiology:[2]

- Gut permeability/barrier function

- Intestinal inflammation

- Exocrine (hormonal) markers

- Bacterial translocation markers

- Endotoxin core antibody

- Markers of systemic inflammation

It is postulated that the limited of understanding of EE is partially due to the paucity of reliable biomarkers, making it difficult for researchers to track the epidemiology of the condition and assess the efficacy of interventions.[9]

Classification[]

In the 1960s, researchers reported a syndrome of non-specific histopathological and functional changes to the small intestine in individuals living in unsanitary conditions.[3] This syndrome was observed predominantly in tropical regions across Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa and Asia. The geographic distribution of the syndrome lead to the original term of "tropical enteropathy" (sometimes also "tropical jejunopathy").[3]

Following initial reports, further investigation revealed that these symptoms were not specific to tropical climates. For example, individuals in more wealthy tropical countries, such as Qatar and Singapore, did not exhibit these symptoms.[1] Similarly, subsequent studies have shown this condition to be common across the developing world, closely associated with impoverished conditions but independent of climate or geography.[1][9] As a result, the term "environmental enteropathy" was introduced to specify that this condition is not only found in tropical areas and is believed to be caused by environmental factors.[3]

Prevention[]

Prevention focuses on improving access to water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH).[14][15]

Another important factor might be contaminated soil in child play spaces, often caused by the presence of livestock such as chicken in the household. Creating a clean play space might therefore be an effective preventive measure for EE in toddlers.[16]

Treatment[]

Treatment focuses on addressing the central components of intestinal inflammation, bacterial overgrowth and nutritional supplementation.[2]

Epidemiology[]

Environmental enteropathy (EE) primarily affects children living in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).[17] Children living in these countries were found to have enteric pathogens related to EE in their systems throughout much of their early childhoods.[17] Gastrointestinal abnormalities associated with EE are not congenital but are acquired during infancy and persist into adulthood.[18][19] Such abnormalities tend to develop after the first semester of life and are not present in newborns.[18]

Historically, environmental enteropathy has been prevalent in LMICs.[19] The geographic distribution of environmental enteropathy has shown an increase in incidence in such areas of poor sanitation and hygiene.[17] EE was first described in studies from the 1960-70s conducted in Asia, Africa, the Indian subcontinent, and Central America, during which it was discovered that signs of EE were high among otherwise healthy adults and children.[20] A study from 1971 following US Peace Corps volunteers is often cited as being the first study to demonstrate the ability to acquire and recover from EE according to the environment.[19] Participants experienced symptoms of chronic enteric infection during and shortly after returning from their placement in low- and middle-income countries.[17] Symptoms experienced by those abroad were resolved within one to two years after returning home to the US.[19] These results lead to the suggestion of the environment being a cause of EE, and a later study in Zambia was able to draw similar conclusions.[19] By the early 1990s, environmental enteropathy was found to be a widespread problem affecting infants and children.[19] Today, enteric infections and diarrheal diseases like environmental enteropathy account for 760,000 deaths per year worldwide, making EE the second leading cause of death in children under five years old.[20]

The exact causes and consequences of EE have been difficult to establish due, in part, to the lack of a clear disease definition.[17] However, risk factors do exist and they can be both environmental and nutritional.[17] Preexisting conditions such as micronutrient deficiencies, diarrheal diseases, and various chronic infections all serve as risk factors for EE.[17] Environmental conditions such as poor sanitation and unimproved water sources also contribute to the prevalence of EE.[17] Exposure to environmental microbial agents such as these is thought to be the most important factor in the development of EE.[18]

Research initiatives[]

There are multiple large-field, multi-country research initiatives focusing on strategies to prevent and treat EE.[9]

- The MAL-ED project

- The Alive and Thrive nutrition project

- The Sanitation, Hygiene and Infant Nutrition Efficacy (SHINE) Trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01824940)

- The WASH Benefits Study

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l Louis-Auguste J, Kelly P (July 2017). "Tropical Enteropathies". Current Gastroenterology Reports. 19 (7): 29. doi:10.1007/s11894-017-0570-0. PMC 5443857. PMID 28540669.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Ali A, Iqbal NT, Sadiq K (January 2016). "Environmental enteropathy". Current Opinion in Gastroenterology. 32 (1): 12–7. doi:10.1097/MOG.0000000000000226. PMID 26574871. S2CID 40064894.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m Korpe PS, Petri WA (June 2012). "Environmental enteropathy: critical implications of a poorly understood condition". Trends in Molecular Medicine. 18 (6): 328–36. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2012.04.007. PMC 3372657. PMID 22633998.

- ^ Ngure FM, Reid BM, Humphrey JH, Mbuya MN, Pelto G, Stoltzfus RJ (January 2014). "Water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH), environmental enteropathy, nutrition, and early child development: making the links". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1308 (1): 118–28. Bibcode:2014NYASA1308..118N. doi:10.1111/nyas.12330. PMID 24571214. S2CID 21280033.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bhutta ZA, Guerrant RL, Nelson CA (April 2017). "Neurodevelopment, Nutrition, and Inflammation: The Evolving Global Child Health Landscape". Pediatrics. 139 (Suppl 1): S12–S22. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-2828d. PMID 28562245.

- ^ Jump up to: a b John CC, Black MM, Nelson CA (April 2017). "Neurodevelopment: The Impact of Nutrition and Inflammation During Early to Middle Childhood in Low-Resource Settings". Pediatrics. 139 (Suppl 1): S59–S71. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-2828h. PMC 5694688. PMID 28562249.

- ^ Oriá RB, Murray-Kolb LE, Scharf RJ, Pendergast LL, Lang DR, Kolling GL, Guerrant RL (June 2016). "Early-life enteric infections: relation between chronic systemic inflammation and poor cognition in children". Nutrition Reviews. 74 (6): 374–86. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuw008. PMC 4892302. PMID 27142301.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Czerkinsky C, Holmgren J (June 2015). "Vaccines against enteric infections for the developing world". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 370 (1671): 20150142. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0142. PMC 4527397. PMID 25964464.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Prendergast A, Kelly P (May 2012). "Enteropathies in the developing world: neglected effects on global health". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 86 (5): 756–63. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0743. PMC 3335677. PMID 22556071.

- ^ Humphrey JH (September 2009). "Child undernutrition, tropical enteropathy, toilets, and handwashing". Lancet. 374 (9694): 1032–1035. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(09)60950-8. PMID 19766883. S2CID 13851530.

- ^ Mbuya MN, Humphrey JH (May 2016). "Preventing environmental enteric dysfunction through improved water, sanitation and hygiene: an opportunity for stunting reduction in developing countries". Maternal & Child Nutrition. 12 Suppl 1: 106–20. doi:10.1111/mcn.12220. PMC 5019251. PMID 26542185.

- ^ Gilmartin AA, Petri WA (June 2015). "Exploring the role of environmental enteropathy in malnutrition, infant development and oral vaccine response". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 370 (1671): 20140143. doi:10.1098/rstb.2014.0143. PMC 4527388. PMID 25964455.

- ^ Louis-Auguste J, Kelly P (July 2017). "Tropical Enteropathies". Current Gastroenterology Reports. 19 (7): 29. doi:10.1007/s11894-017-0570-0. PMC 5443857. PMID 28540669.

- ^ Mbuya MN, Humphrey JH (May 2016). "Preventing environmental enteric dysfunction through improved water, sanitation and hygiene: an opportunity for stunting reduction in developing countries". Maternal & Child Nutrition. 12 Suppl 1: 106–20. doi:10.1111/mcn.12220. PMC 5019251. PMID 26542185.

- ^ Ngure FM, Reid BM, Humphrey JH, Mbuya MN, Pelto G, Stoltzfus RJ (January 2014). "Water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH), environmental enteropathy, nutrition, and early child development: making the links". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1308 (1): 118–28. Bibcode:2014NYASA1308..118N. doi:10.1111/nyas.12330. PMID 24571214. S2CID 21280033.

- ^ George CM, Burrowes V, Perin J, Oldja L, Biswas S, Sack D, et al. (January 2018). "Enteric Infections in Young Children are Associated with Environmental Enteropathy and Impaired Growth". Tropical Medicine & International Health. 23 (1): 26–33. doi:10.1111/tmi.13002. PMID 29121442.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Tickell KD, Atlas HE, Walson JL (November 2019). "Environmental enteric dysfunction: a review of potential mechanisms, consequences and management strategies". BMC Medicine. 17 (1): 181. doi:10.1186/s12916-019-1417-3. PMC 6876067. PMID 31760941.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Morais MB, Silva GA (2019-03-01). "Environmental enteric dysfunction and growth". Jornal de Pediatria. 95 Suppl 1: 85–94. doi:10.1016/j.jped.2018.11.004. PMID 30629923.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Crane RJ, Jones KD, Berkley JA (March 2015). "Environmental enteric dysfunction: an overview". Food and Nutrition Bulletin. 36 (1 Suppl): S76-87. doi:10.1177/15648265150361S113. PMC 4472379. PMID 25902619.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Syed S, Ali A, Duggan C (July 2016). "Environmental Enteric Dysfunction in Children". Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 63 (1): 6–14. doi:10.1097/MPG.0000000000001147. PMC 4920693. PMID 26974416.

- Human diseases and disorders

- Tropical diseases

- Neglected tropical diseases

- Intestinal infectious diseases

- Sanitation

- Environmental health