Eugenio Espejo

Eugenio Espejo | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | February 21, 1747 Quito, Spanish Empire |

| Died | December 28, 1795 (aged 48) Quito, Spanish Empire |

| Occupation | Writer, lawyer, physician |

Francisco Javier Eugenio de Santa Cruz y Espejo[a] (Royal Audiencia of Quito, February 21, 1747 – December 28, 1795) was a medical pioneer, writer and lawyer of mestizo origin in colonial Ecuador. Although he was a notable scientist and writer, he stands out as a polemicist who inspired the separatist movement in Quito. He is regarded as one of the most important figures in colonial Ecuador. He was Quito's first journalist and hygienist.

As a journalist he spread enlightened ideas in the Royal Audiencia, and as a hygienist he composed an important treatise about sanitary conditions in colonial Ecuador that included interesting remarks about microorganisms and the spreading of disease.

Espejo was noted in his time for being a satirist. His satirical works, inspired by the philosophy of the Age of Enlightenment, were critical of the lack of education of the Audiencia of Quito, the way the economy was being handled in the Audiencia, the corruption of its authorities, and aspects of its culture in general. Because of these works he was persecuted and finally imprisoned shortly before his death.

Historical background[]

The Royal Audiencia of Quito (or Presidency of Quito) was established as part of the Spanish State by Philip II of Spain on August 29, 1563. It was a court of the Spanish Crown with jurisdiction over certain territories of the Viceroyalty of Peru (and later the Viceroyalty of New Granada) that now constitute Ecuador and parts of Peru, Colombia and Brazil. The Royal Audiencia was created to strengthen administrative control over those territories and to rule the relations between whites and the natives. Its capital was the city of Quito.[1]

By the 18th century, the Royal Audiencia of Quito began to have economic problems; a lack of roads led to limited communications. Obrajes—a type of textile factory—had provided jobs, but now found themselves in decline, mainly due to a crackdown on smuggled European cloths and a series of natural disasters.[2] Obrajes were replaced by haciendas, and the dominant groups continued to exploit the indigenous population.[3]

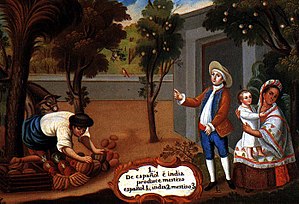

In the Royal Audiencia, the education situation worsened after of the expulsion of the Jesuit priests; too few learned people lived in Quito to be able to fill the void. The majority of the population neither read nor wrote well. On the other hand, the few who could enter the university were given an education which was heavily theoretical and used memorization as the primary learning technique.[4] Scholasticism, which was in decline in these times, was still taught; and the students spent their time in metaphysical discussions. As a result, the intellectual people in Quito—most of whom were clerical—had affected manners when expressing themselves, while having no new ideas. Furthermore, in 1793 only two medical doctors were available in Quito, of which one was Espejo; the majority of people who fell ill were helped by curanderos.[5] In Quito at the time, ethnic prejudice was common, and therefore most people considered society to be divided into estates of the realm, which differed by racial origin. Because of this, a person's dignity and honor could be damaged by racial prejudices.[6]

A slackening of social customs occurred on all social levels; extramarital relationships and illegitimate children were common.[7] Because poverty was on the rise—especially in the lower classes—many women were forced to find lodgings quickly, for example in convents, o. This explained the abundance of the clergy in a small city like Quito; often men were ordained not because of a vocation but because it solved their economic problems and improved their community standing.[8]

Biography[]

Early life[]

He was baptized Francisco Javier Eugenio de Santa Cruz y Espejo in the El Sagrario parish on February 21, 1747. According to most historians, his father was Luis de la Cruz Chuzhig, a Quichua Indian from Cajamarca, who arrived in Quito as an assistant to the priest and physician José del Rosario, and his mother was Maria Catalina Aldás, a mulatta native to Quito. However, some historians, especially , argue that contemporary documents imply that Espejo's mother was white; for instance, his parents' marriage was recorded in the book for white marriages (as they were deemed as criollos), and the birth certificates of Espejo and his siblings were entered in the same book.[9][10][b]

Espejo had two younger siblings, Juan Pablo and María Manuela. Juan Pablo was born in 1752; he studied with the Dominicans and served as a priest in various parts of the Audiencia of Quito. María Manuela was born in 1753, and after the death of her parents she came to be cared for by her brother Eugenio.[11] Despite his family's somewhat unstable economic situation, Espejo had a good education. He instructed himself in medicine by working alongside his father at the Hospital de la Misericordia. According to Espejo, he learned "by experience, which cannot be known without studying with pen in hand."[12]

Overcoming racial discrimination, he graduated from medical school on July 10, 1767, and shortly afterwards graduated in jurisprudence and canon law (having studied law under Dr. Ramón Yépez from 1780 to 1793). On August 14, 1772, he asked for permission to practice medicine in Quito, and it was granted on November 28, 1772.[13] After that, no information exists about Espejo's whereabouts until 1778, when he wrote a somewhat polemical sermon.[14]

Activities in the Royal Audiencia[]

Work as a polemicist[]

Between 1772 and 1779, Espejo provoked the colonial authorities, who regarded him as responsible for several satirical and mocking posters. These posters were attached to the doors of churches and other buildings, and their anonymous author tended to attack the colonial authorities, the clergy or any other subject he deemed convenient. Although no surviving posters have been found, evidence from comments Espejo made in his writings suggests that he wrote them.[15]

In 1779, a reproachful and satirical manuscript was circulated, the El nuevo Luciano de Quito (The New Lucian of Quito),[c] signed by "don Javier de Cía, Apéstegui y Perochena," a pseudonym for Espejo. This work imitated the satire of Lucian, and was especially unsympathetic to the Jesuits. It showed the culture of its author, who lived in the isolated and intellectually backward city of Quito. El Nuevo Luciano de Quito was written in dialogues, in order to present his ideas to the common people in an easy way, instead of using tedious explanations meant for scholars.[16] It satirized the many defects of the society of Quito, especially the corruption of the colonial authorities and the people's lack of education. The use of a pseudonym, a common practice in Europe and the Americas during the Age of Enlightenment, was important to Espejo. Not only did it provide anonymity, it attempted to remove any hint of his crossbreeding in a culture which granted any white person importance and prestige. His pseudonym implied that he had white or European relatives in his mother's lineage.[d]

Beginning in 1779, Espejo continued writing satires against the government of the Audiencia, stirred by the condition of society. In June 1780, Espejo wrote Marco Porcio Catón (Marcus Porcius Cato),[e] Once again, Espejo used a pseudonym, "Moisés Blancardo." In this work, a parodied censor's response to the Nuevo Luciano, he scorned the notions and ideas of its critics. In 1781 he wrote La ciencia blancardina, which he referred to as the second part of Nuevo Luciano, as an answer to the criticism of a Mercedarian priest from Quito.[17] Because of his works, by 1783 he was labeled as "restive and subversive."[18] To get rid of him, the authorities named him head physician for the scientific expedition of Francisco de Requena to the Pará and Marañon rivers to set the limits of the Audiencia. Espejo tried to decline the appointment, and after that failed, he tried unsuccessfully to flee. His arrest order details one of the few remaining physical descriptions of him.[f] Captured, he was sent back as a "criminal of serious offense,"[19] but he was not prosecuted and suffered no significant consequences.

Short exile[]

In 1785, he was asked by the cabildo (town council) to write about smallpox, the worst medical problem the Audiencia faced. Espejo used the opportunity to write his most complete and best-written work,[20][21] Reflexiones acerca de un método para preservar a los pueblos de las viruelas (Reflections about a method to preserve the people from smallpox), denouncing the way the Audiencia handled sanitation. This work is a valuable historical source as a description of the hygienic and sanitary conditions of colonial America.

Reflexiones was sent to Madrid, where it was added as an appendix to the second edition of the medical treatise Disertación médica (1786) by Francisco Gil, a member of the Real Academia Médica de España.[22] Instead of recognition, Espejo acquired enemies because his work criticized the physicians and priests in charge of public health in the Royal Audiencia for their negligence, and he was forced to leave Quito.

On his way to Lima, he stopped in Riobamba, where a group of priests asked him to write a reply to a report written by Ignacio Barreto, chief tax collector. The report accused the priests of Riobamba of various abuses against the Indians in order to take their money. Espejo gladly accepted the task because he wanted to settle accounts with Barreto and other citizens of Riobamba, among them José Miguel Vallejo, who had turned him in to the authorities when he tried to flee Requena's expedition to the Marañón river.[23] He wrote Defensa de los curas de Riobamba (Defense of the clergy of Riobamba), a detailed study of the way of life of the Indians from Riobamba and a powerful attack on Barreto's report.

In March 1787, he continued his attack against his enemies from Riobamba with a series of eight satirical letters which he called Cartas riobambenses. In response, his enemies denounced Espejo before the President of the Royal Audiencia, Juan José De Villalengua. On August 24, 1787, Villalengua requested that Espejo either to go to Lima or return to Quito to occupy a post in the government,[24] and subsequently arrested him. Espejo was accused of writing El Retrato de Golilla, a satire against King Charles III and the Marquis de la Sonora, colonial minister of the Indies. He was taken to Quito, and from prison he sent three petitions to the Court in Madrid, which decreed, on Charles III's behalf, that the case was to be taken to the Viceroy of Bogotá. President Villalengua feigned ignorance of the matter and sent Espejo to Bogotá to defend his own cause.[25]

There he met Antonio Nariño and Francisco Antonio Zea and began to develop his ideas on liberty. In 1789, one of his followers, Juan Pio Montufar, arrived in Bogotá, and both men got the approval of important members of the government for the creation of the Escuela de la Concordia, called later the Sociedad Patriótica de Amigos del País de Quito (Patriotic Society of Friends of the Country of Quito).[26] The Sociedad Económica de los Amigos del País (Economic Society of Friends of the Country) was a private association established in various cities throughout Enlightenment Spain and, to a lesser degree, in some of her colonies. Espejo successfully defended himself on the charges against him, and on October 2, 1789, he was set free. On December 2 he was notified he could return to Quito.[26]

Final years[]

In 1790, Espejo returned to Quito to promote the "Sociedad Patriótica" (Patriotic Society), and on November 30, 1791, a branch was established in the Colegio de los Jesuitas; he was elected director and formed four commissions. In the same year, he became director of the first public library, the National Library, originally established with the forty thousand volumes left by the Jesuits after their expulsion from Ecuador.[27]

The main duty of the Society was improving the city of Quito. Its 24 members came together weekly to discuss agricultural, educational, political and social problems and to promote the physical and natural sciences. The Society founded Quito's first newspaper, Primicias de la Cultura de Quito, published by Espejo starting on January 5, 1792. Through this newspaper liberal ideas, already somewhat known in other parts of Hispanic America, were spread among the people of Quito.[28]

On November 11, 1793, Charles IV dissolved the society.[29] Soon the newspaper disappeared as well. Espejo had no choice but to work as a librarian in the National Library. Because of his liberal ideas, he was imprisoned[g] on January 30, 1795, being allowed to leave his cell only to treat his patients as a doctor and, on December 23, to die at his home from the dysentery he acquired during his imprisonment.[30] Eugenio Espejo died on December 28. His death certificate was registered in the book for Indians, mestizos, blacks and mulattoes.

Character[]

Eugenio Espejo was an autodidact, and he claimed with pride that he never left any book in his hands unread, and if he did, he would make up for it by observing nature. However, his desire to read everything indiscriminately sometimes led him to hasty judgments, which appear in his manuscripts.[31][h] Through his own written work, it can be inferred that Espejo considered education as the main means for popular development. He understood that reading was basic in the formation of the self, and his conscience drove him to critiques of the establishment, based on observation and in the application of the law of his time.[27]

By his writing, Espejo wanted to educate the people and to awaken a rebellious spirit in them. He embraced equality between Indians and criollos, an ideal that was ignored during the future processes of autonomy.[i] He also favored women's rights but did not really develop these ideas.[j] He had an advanced understanding of science, considering the circumstances in which he lived. He never traveled abroad but nonetheless understood the relation between microorganisms and the spreading of disease.[32][k]

When he was arrested, it was rumored that his detention resulted from his support of the "impieties" of the French Revolution.[30] However, Espejo was one of the few people at the time who distinguished between the actual deeds of the French Revolution and the irreligious spirit connected to it, while his contemporaries in Spain and the colonies erroneously identified the emancipation of the Americas with loss of the Catholic faith. The accusation of impiety was calculated to incite popular hatred against him. Espejo never lost his faith in Catholicism throughout his lifetime. He condemned the decadence of the clergy, but he never criticized the Church itself.[33] Eugenio Espejo had a restless desire for knowledge and was anxious to reform by his works a state that seemed to him, influenced as he was by the Enlightenment, to be barbarian in every way.[34]

Thought[]

Views on education[]

The goal of Espejo's first three works was the intellectual improvement of Quito. El Nuevo Luciano de Quito ridiculed the outdated educational system maintained by the clergy. Espejo argued that the people of Quito were accustomed to adulation and that they admired any preacher who could quote the Bible in a pompous and insubstantial way. Marco Porcio Catón exposed the ignorance of the pseudointellectuals of Quito. La ciencia blancardina, in which Espejo claimed to be the author of the previous two works, condemned the results of the clergy's educational system: ignorance and affectation.[35] All three works caused polemic.

Through these three books, Espejo advanced the ideas of European and American scholars such as Feijoo and the Jesuits Verney and Guevara, among others. As a result, many religious orders modified their educational programs. Espejo resented the pseudointellectuals who misled the thought of the city of Quito, disregarding people who were actually knowledgeable.[36]

Espejo particularly criticized the Jesuits for, among other things, teaching ethics not as a science but as a guide to good manners and for their adoption of Probabilism as a moral guide.[37] He complained about the lax system for educating priests in Quito and said it instilled slothful habits in students. As a result, the priests had no real idea of their duties towards society and God and had little inclination to study. In El Nuevo Luciano de Quito, he lamented the large number of quacks who pretended to be doctors. In La ciencia blancardina he continued his attack on these quacks while attacking clerics who worked as physicians without adequate medical education.[38]

Views on theology[]

In 1780, in his first discussion of purely religious matters, Espejo wrote a theological letter, Carta al Padre la Graña sobre indulgencias (Letter to Father la Graña about indulgences).[l] In this work, he looked at indulgences in the Catholic Church. The letter showed a profound knowledge of theology and dogma. It analyzed the historical beginnings of indulgences and their development and cited decrees and bulls written about abuses of indulgences.[39] In this work, Espejo staunchly supported the authority of the Pope.

On July 19, 1792, Espejo wrote another letter, Segunda carta teológica sobre la Inmaculada Concepción de María (Second theological letter about Mary's Immaculate Conception), in response to a request by the inspector of the Holy Office.[m] This letter dealt with the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary. Once more, this work showed its author's deep knowledge of this religious subject and his appreciation of its standing in the 18th century. (The Immaculate Conception was not formally decreed as dogma until 1950.)[40]

Espejo also wrote a series of sermons, which were notable in their simplicity. Ecuadorian historian and cleric Federico González Suárez considered these sermons worthy of study, even though he mentioned that they lacked an "evangelic spirit."[41] Espejo can be considered a deeply religious man.[42]

Views on economics[]

Starting in 1785, Espejo took an interest in the welfare of his community and the prosperity of Quito. His works between that year and 1792 clearly show the influence of Enlightenment philosophers, whose ideas Espejo adapted to local conditions. As many thinkers realized the power of economics as a social force, Espejo, influenced by Feijoo and Adam Smith among others, showed his desire for commercial and agricultural reforms, especially conservation and proper use of land. To advance these ideas, he founded the Escuela de la Concordia (School of Concord).[43]

His Voto de un ministro togado de la Audiencia de Quito and Memorias sobre el corte de quinas rejected a proposed monopoly of quinine production by the Crown intended to prevent the destruction of the cinchona tree and to expand the Royal Treasury's income. Memorias was dedicated to Fernando Cuadrado, who opposed the monopoly.[44]

Espejo divided his cinchona study into four parts. In the first, he argued that the monopoly would leave workers without jobs and that it would mean the loss of capital invested in cinchona trees. In the second part, he made a number of suggestions, such as developing certain "natural" products of a region with the aim of exporting them. For instance, in Chile the production of wines should be prioritized, in Argentina the production of leather, and so forth. In the third part he showed that many workers benefited from the quinine industry, that without it there would be unemployment and unrest, and that the Crown should designate officials to regulate the proper cultivation of the cinchona tree, including reforestation. In the fourth part he made recommendations, such as the need to repress indigenous hostility in the cinchona tree region.[45]

Work as a lawyer[]

His Defensa de los curas de Riobamba was written in response to a report from Ignacio Barreto that accused the clergy in Riobamba of various unethical practices. Among other things, the report said that the large number of religious celebrations in Riobamba (frequented by Indians) were prejudicial to Catholic faith, agriculture, industry and the interests of the Crown; also, that priests demanded money from the Indians for entrance into churches and for certain ceremonies, that priests in Riobamba were immoral and finally that most sermons were incomprehensible to the Indians.[46]

Espejo attacked Barreto's report in three ways. First, he claimed that Barreto, supposed author of the report, was not capable of writing it. Then he argued that the allegations were exaggerated semi-truths or outright lies. And finally he claimed that the economic problems of Quito could not be solved by exploiting its human resources (the Indians) but by planning and taking advantage of the natural resources of the region.[46]

Espejo realized that the charges against the clergy were so serious that he had to focus on destroying Barreto's credibility. Therefore, he implied that Barreto's own conduct was outrageous because of his excesses in collecting taxes and his habit of paying public funds to licentious women. Additionally, he stated that the real author of the report was José Miguel Vallejo, whom he called an immoral man who despised the clergy. Thus, Espejo claimed the report should not be believed.[47]

It appears that Espejo was motivated more by the opportunity to attack his personal enemies in this work than to analyze the case and defend the clergy of Riobamba. Still, his talent as a lawyer can be seen in his Representaciones (Representations), which caused him to be freed after his arrest in 1787 for his supposed authorship of El Retrato de Golilla.[48] In these documents, he defended his loyalty to the Crown, commented on the unfairness of his captivity by mentioning the indignation that many distinguished men felt about his arrest, and clarified his writing goals. This served him as a prelude to his main subject: denying being the author of El Retrato de Golilla

Scientific work[]

The Spanish Crown was deeply concerned with public health. Diseases had always troubled the colonies, and town councils spent money to bring physicians or sanitary equipment from other parts of the Americas. Reports by doctors about the sanitary and hygienic conditions of various neighborhoods of the cities were frequent.[49] As a man of science, Eugenio Espejo demonstrated his knowledge of the latest scientific advances in Europe and the Americas. Most of the arguments and recommendations he made in his medical works can be found in contemporary sources, such as the Mémoires of the French Academy of Sciences.[50]

The Presidency of Quito was especially concerned with prevention of smallpox. Villalengua, President of the Audiencia, gathered all of Quito's physicians to discuss the application of methods suggested by the Spanish scientist Francisco Gil, and Espejo was asked to write his Reflexiones acerca de un método para preservar a los pueblos de las viruelas."[n] Reflexiones, completed on November 11, 1785, was divided in two parts: the first dealt with prevention of smallpox in Quito, while the second dealt with obstacles on the path to its eradication. Espejo's knowledge of inoculations and the quarantine of smallpox victims was remarkably advanced for his day.[20]

Reflexiones recommended using proven methods supported by Spanish and foreign doctors. It refuted the common belief that the separation and destruction of contaminated clothes was impractical, and it promoted personal hygiene among the people of Quito. Espejo tried to convince people of the dangers of smallpox. He understood the current European medical theories about contagious diseases and warned against the incorrect belief that smallpox was transmitted by polluted air. Citing the English doctor Thomas Sydenham, he suggested the construction of an isolated country house as a hospital.[51]

Dealing with sanitation, Espejo observed that the hospital (Hospital de la Misericordia) of the city, the monasteries and the places of worship were filthy and that this would certainly contribute to future epidemics. He disapproved of the custom of burying the dead inside churches; instead, he suggested burying the dead outside the city limits in a graveyard chosen by the Church and owned by the town council.[52] Finally, he condemned the management of the hospital by the Bethlehemites. He said their methods were outdated and that they provided poor service. The staff of the hospital reacted badly to this, and Espejo lost the friendship of his mentor, José del Rosario.[53]

Legacy[]

Espejo is considered the precursor of the independence movement in Quito. He died in 1795, but his ideas had a powerful influence on three of his close friends: , Juan de Dios Morales and Juan de Salinas. They, along with , founded the revolutionary movement of August 10, 1809, in Quito, when the city declared independence from Spain.[54]

Espejo published Quito's first newspaper, and therefore he is regarded as the founder of Ecuadorian journalism. He is considered Ecuador's first literary critic; according to Spanish scholar Marcelino Menéndez y Pelayo, Espejo's Nuevo Luciano is the oldest critical work written in South America.[55]

His influence can as well be seen in Ecuadorian thought in general, as his work has been one of its principal influences; Ecuadorian education, as he promoted new pedagogical ideas, such as the creation of good citizens instead of merely imparting knowledge,[56] and finally Ecuadorian science, as he was, along with Pedro Vicente Maldonado, one of the two most important scientists of colonial Ecuador.[57] Espejo analyzed the reality of colonial Quito, the poverty of its people and their lack of good education, and he denounced the corruption of the colonial authorities.[58]

Since 2000, Espejo has been depicted on the obverse of Ecuador's 10 centavo coin.

Works[]

Biography portal

Biography portal Ecuador portal

Ecuador portal

- Sermones para la profesión de dos religiosas (1778)

- Sermón sobre los dolores de la Virgen (1779)

- Nuevo Luciano de Quito (1779)

- Marco Porcio Catón o Memorias para la impugnación del nuevo Luciano de Quito (1780)

- Carta al Padre la Graña sobre indulgencias (1780)

- Sermón de San Pedro (1780)

- La Ciencia Blancardina (1781)

- El Retrato de Golilla (Attributed, 1781)

- Reflexiones acerca de un método para preservar a los pueblos de las viruelas (1785) Online version (Spanish)

- Defensa de los curas de Riobamba (1787)

- Cartas riobambenses (1787)

- Representaciones al presidente Villalengua (1787)

- Discurso sobre la necesidad de establecer una sociedad patriótica con el nombre de "Escuela de la Concordia" (1789)

- Segunda carta teológica sobre la Inmaculada Concepción de María (1792)

- Memorias sobre el corte de quinas (1792)

- Voto de un ministro togado de la Audiencia de Quito (1792) Online version (Spanish)

- Sermón de Santa Rosa (1793)

Notes[]

a. ^ There are discrepancies about the origin of the surnames "Santa Cruz y Espejo;" José del Rosario declared that his father, Luis Espejo, was first named Benítez, changed his surname to Chusig and finally to Espejo. Ecuadorian researcher Alberto Muñoz Vernaza claimed that his real surname was Espejo and that the name Chusig (owl) was a nickname Espejo had in Cajamarca. According to José del Rosario, the surname "Santa Cruz" was added "because of devotion" (Astuto, Philip L., Eugenio Espejo (1747–1795). Reformador ecuatoriano de la Ilustración, p. 73).

b. ^ Freile maintains that the notion of Espejo's indigenous origins sustained by most modern historians comes from their interpretation of the claims made against him by his contemporary enemies, who called him "indio" (Indian) in order to slander him in a racist society.

c. ^ Its full name is El nuevo Luciano de Quito o Despertador de los ingenios quiteños en nueve conversaciones eruditas para el estímulo de la literatura.

d. ^ Aware of the prejudices of the society of his time, Espejo requested a dossier that proved his Spanish lineage. The dossier mentioned that Espejo's mother was born from a noble Navarran family. When he asked for the post of librarian in 1781, he showed that certificate (Astuto, 78–79).

e. ^ Its full name is Marco Porcio Catón o Memorias para la impugnación del nuevo Luciano de Quito.

f. ^ "He has average height, long face, long nose, tanned skin, and a visible hole on the left side of his face" (Herrera, Pablo, Ensayo sobre la historia de la literatura ecuatoriana, pp. 125, 145).

g. ^ The authorities finally found evidence against Espejo when his brother, Juan Pablo, told his lover, Francisca Navarrete, about the plans of Eugenio. He was charged with treachery to the Crown (Astuto, 94).

h. ^ One of his characters thought it paradoxical to live in what he called "the era of idiocy and . . . the century of ignorance" and yet refer to it as the Age of Enlightenment. (Weber, David J., Spaniards and Their Savages in the Age of Enlightenment, p. 5).

i. ^ "Los miserables indios, en tanto que no tengan, por patrimonio y bienes de fortuna, más que sólo sus brazos, no han de tener nada que perder. Mientras no los traten mejor; no les paguen con más puntualidad, su cortísimo salario; no les aumenten el que deben llevar por su trabajo; no les introduzcan el gusto de vestir, de comer, y de la policía en general; no les hagan sentir que son hermanos, nuestros estimables y nobilísimos siervos, nada han de tener que ganar, y por consiguiente la pérdida ha de ser ninguna" (Biblioteca de Autores Ecuatorianos de Clásicos Ariel, 24).

j. ^ According to Philip Astuto, "He thought that the solution to such plain ignorance was the construction of schools and the education of youth without excluding women" (Astuto, 93).

k. ^ "Si se pudieran apurar más las observaciones microscópicas, aún más allá a lo que las adelantaron Malpigio, Reaumur, Buffon y Needham, quizá encontraríamos en la incubación, desarrollamiento, situación, figura, movimiento y duración de estos corpúsculos móvibles, la regla que podría servir a explicar toda la naturaleza, grados, propiedades y síntomas de todas las fiebres epidémicas, y en particular de la Viruela" (Biblioteca de Autores Ecuatorianos de Clásicos Ariel, 22).

l. ^ Its full name is Carta del padre La Graña del orden de San Francisco, sobre indulgencias escrita por el mismo doctor Espejo, tomando el nombre de este padre que fue sabio y de gran erudición.

m. ^ In 1792, the Dominicans of the Convento Máximo de Quito published a series of theological theses. One of them stated that original sin was transmitted to every single descendant of Adam, without exception. As it never mentioned the subject of the Virgin Mary, it was rumoured that the Dominicans took the view that Mary was born with original sin. The Inspector denounced the thesis, and in face of the protest of the Dominicans, entrusted Espejo with replying to the Dominican thesis and rebutting their ideas (Astuto, 138).

n. ^ Its full name is Reflexiones sobre la virtud, importancia y conveniencias que propone don Francisco Gil, cirujano del Real Monasterio de San Lorenzo y su sitio, e individuo de la Real Academia Médica de Madrid, en su Disertación físico-médica, acerca de un método seguro para preservar a los pueblos de las viruelas.

Citations[]

- ^ Enciclopedia del Ecuador, 425

- ^ Freile, Carlos (1997). Eugenio Espejo y su tiempo, p. 37

- ^ Freile, 38

- ^ Freile, 39–40

- ^ Freile, 40

- ^ Freile, 41–46

- ^ Freile, 45–46

- ^ Freile, 46

- ^ Freile 54

- ^ Freile, Carlos (1997). Eugenio Espejo, Filósofo, p. 50

- ^ Freile, 58

- ^ Biblioteca de Autores Ecuatorianos de Clásicos Ariel, No. 56, Tome I, p.12. (citation from La ciencia blancardina, pp. 333–334)

- ^ Enciclopedia del Ecuador, 746

- ^ Freile, 60

- ^ Astuto, Philip L. (2003). Eugenio Espejo (1747–1795). Reformador ecuatoriano de la Ilustración, p. 76-77

- ^ Paladines, Carlos. (2007). Juicio a Eugenio Espejo, p. 24

- ^ Astuto, 82

- ^ Biblioteca de Autores Ecuatorianos de Clásicos Ariel, 15

- ^ Paladines, 32

- ^ a b Astuto, 177

- ^ Garcés, Enrique (1996). Eugenio Espejo: Médico y duende, p. 110

- ^ Paladines, 38

- ^ Astuto, 85

- ^ Astuto, 86

- ^ Paladines, 39

- ^ a b Astuto, 88

- ^ a b Enciclopedia del Ecuador, 747

- ^ Astuto, 92–93

- ^ Freile, 64

- ^ a b Astuto, 95

- ^ Astuto, 75

- ^ Eugenio Espejo, Bacteriólogo

- ^ Confront with Astuto, 95

- ^ Confront with Weber, p.5

- ^ Astuto, 99

- ^ Freile, 67

- ^ Astuto, 114–115

- ^ Astuto, 119

- ^ Astuto, 137

- ^ Astuto, 138

- ^ Astuto, 139

- ^ Astuto, 143

- ^ Astuto, 145–146

- ^ Astuto, 150

- ^ Astuto, 151–155

- ^ a b Astuto, 156–157

- ^ Astuto, 157

- ^ Paladines, 40–42

- ^ Astuto, 175–176

- ^ Astuto, 176

- ^ Astuto, 178

- ^ Astuto, 179

- ^ Astuto, 182

- ^ Hurtado, Osvaldo (2003). El Poder Político en el Ecuador, p. 50

- ^ Enciclopedia del Ecuador, 509

- ^ Enciclopedia del Ecuador, 642

- ^ Biblioteca de Autores Ecuatorianos de Clásicos Ariel, 10

- ^ Freile, 82

References[]

Note: There is no available bibliography in English about Eugenio Espejo.

Primary sources[]

- Astuto, Philip L. (2003). Eugenio Espejo (1747–1795). Reformador ecuatoriano de la Ilustración. Casa de la Cultura Ecuatoriana. ISBN 9978-92-241-5.

- Freile, Carlos (1997). Eugenio Espejo y su tiempo. Abya-Yala. ISBN 9978-04-266-0.

Secondary sources[]

- Freile, Carlos (1997). Eugenio Espejo, Filósofo. Abya-Yala.

- Paladines, Carlos (2007). Juicio a Eugenio Espejo. Casa de la Cultura Ecuatoriana. ISBN 978-9978-62-454-8.

- Landázuri, Andrés (2011). Espejo, el ilustrado, Quito, INPC. ISBN 978-9942-07-162-0

- Hurtado, Osvaldo (2003). El Poder Político en el Ecuador (15th ed.). Planeta. ISBN 84-344-4231-0.

- Various (2002). Enciclopedia del Ecuador. Océano. ISBN 84-494-1448-2.

- Herrera, Pablo (1960). Ensayo sobre la historia de la literatura ecuatoriana. Imprenta del Gobierno.

- Biblioteca de Autores Ecuatorianos de Clásicos Ariel, n.d., No. 56, Tome I

- "Eugenio Espejo, Bacteriólogo" (PDF) (in Spanish). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 17, 2006. Retrieved August 11, 2006.

- Weber, David J. "Spaniards and Their Savages in the Age of Enlightenment" (PDF). Yale University Press.

- Roche, Marcel (1976). "Early History of Science in Spanish America" (PDF). Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science. 194 (4267): 806–10. Bibcode:1976Sci...194..806R. doi:10.1126/science.194.4267.806. PMID 17744170. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 6, 2012.

- 1747 births

- 1795 deaths

- Ecuadorian lawyers

- Ecuadorian people of Quechua descent

- Ecuadorian physicians

- Ecuadorian Roman Catholics

- Ecuadorian satirists

- Ecuadorian scientists

- Ecuadorian male writers

- Enlightenment philosophers

- Enlightenment scientists

- Mestizo writers

- People from Quito

- Rhetoricians

- Roman Catholic writers

- Ecuadorian independence activists