Fallingwater

| Fallingwater | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Mill Run, Pennsylvania |

| Nearest city | Uniontown |

| Coordinates | 39°54′22″N 79°28′5″W / 39.90611°N 79.46806°WCoordinates: 39°54′22″N 79°28′5″W / 39.90611°N 79.46806°W |

| Built | 1936–1939 |

| Architect | Frank Lloyd Wright |

| Architectural style(s) | Modern architecture |

| Visitors | about 135,000 |

| Governing body | Western Pennsylvania Conservancy |

UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| Criteria | Cultural: (ii) |

| Designated | 2019 (43rd session) |

| Part of | The 20th-Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright |

| Reference no. | 1496-005 |

| State Party | United States |

| Region | Europe and North America |

U.S. National Register of Historic Places | |

| Designated | July 23, 1974[1] |

| Reference no. | 74001781[1] |

| Designated | May 23, 1966[2] |

Pennsylvania Historical Marker | |

| Designated | May 15, 1994[3] |

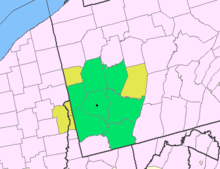

Location of Fallingwater in Pennsylvania | |

Fallingwater is a house designed by the architect Frank Lloyd Wright in 1939 in the Laurel Highlands of southwest Pennsylvania, about 70 miles (110 km) southeast of Pittsburgh.[4] The house was built partly over a waterfall on Bear Run in the Mill Run section of Stewart Township, Fayette County, Pennsylvania, located in the Laurel Highlands of the Allegheny Mountains. The house was designed as a weekend home for Liliane and Edgar J. Kaufmann, the owner of Kaufmann's Department Store.

After its completion, Time called Fallingwater Wright's "most beautiful job"[5] and it is listed among Smithsonian's "Life List of 28 Places to See Before You Die."[6] The house was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1966.[2] In 1991, members of the American Institute of Architects named Fallingwater the "best all-time work of American architecture" and in 2007, it was ranked 29th on the list of America's Favorite Architecture according to the AIA.[7]

The house and seven other Wright constructions were inscribed as a World Heritage Site under the title "The 20th-Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright" in July 2019.[8]

History[]

At age 67, Frank Lloyd Wright was given the opportunity to design and construct three buildings. With his three works of the late 1930s—Fallingwater; the Johnson Wax Building in Racine, Wisconsin; and the Herbert Jacobs house in Madison, Wisconsin—Wright regained his prominence in the architectural community.[9]

The Kaufmanns[]

Edgar J. Kaufmann was a Pittsburgh businessman and president of Kaufmann's Department Store. Liliane Kaufmann, like her husband, was a keen outdoors person; she enjoyed both hiking and horseback riding. She had a strong aesthetic sensibility which is reflected in the house's design.[10]

Edgar and Liliane's only child, Edgar Kaufmann Jr., became the catalyst for his father’s relationship with Frank Lloyd Wright.[10] In the summer of 1934, Kaufmann read Frank Lloyd Wright’s An Autobiography (1932) and traveled to meet him at his home in Wisconsin in late September. Within three weeks, he began an apprenticeship at the Taliesin Fellowship, a communal architecture program established in 1932 by Wright and his wife, Olgivanna. It was during a visit with their son at Taliesin in November 1934 that Edgar and Liliane Kaufmann first met Wright.[10]

The Kaufmanns lived in "La Tourelle," a French Norman estate in Fox Chapel designed in 1923 by Pittsburgh architect Benno Janssen. However, the family also owned a remote property outside Pittsburgh—a small cabin near a waterfall—which was used as a summer retreat. When these cabins deteriorated, Kaufmann contacted Wright.

On December 18, 1934, Wright visited Bear Run and asked for a survey of the area around the waterfall.[11] One was prepared by Fayette Engineering Company of Uniontown, Pennsylvania, including all the site's boulders, trees, and topography, and forwarded to Wright in March 1935.[12]

Construction[]

As reported by Frank Lloyd Wright's apprentices at Taliesin, Kaufmann was in Milwaukee on September 22, nine months after their initial meeting, and called Wright at home early Sunday morning to surprise him with the news that he would be visiting him that day. Wright had told Kaufmann in earlier communications that he had been working on the plans but had not actually drawn anything. After breakfast, amid a group of very nervous apprentices, Wright calmly drew the plans in the two hours in which it took Kaufmann to drive to Taliesin.[13] Witness Edgar Tafel, an apprentice at the time, stated later that when Wright was designing the plans he spoke of how the spaces would be used, directly linking form to function.[14]

Wright designed the home above the waterfall: Kaufmann had expected it to be below the falls to afford a view of the cascades.[15][16] It has been said that he was initially very upset with this change.[11]

The Kaufmanns planned to entertain large groups so the house needed to be larger than the original plot allowed. They also requested separate bedrooms as well as a bedroom for their adult son and an additional guest room.[11] A cantilevered structure was used to address these requests.[11] The structural design for Fallingwater was undertaken by Wright in association with staff engineers Mendel Glickman and William Wesley Peters, who had been responsible for the columns in Wright’s revolutionary design for the Johnson Wax Headquarters.

Preliminary plans were issued to Kaufmann for approval on October 15, 1935,[17] after which Wright made an additional visit to the site to generate a cost estimate for the job. In December 1935, an old rock quarry was reopened to the west of the site to provide the stones needed for the house’s walls. Wright visited only periodically during construction, assigning his apprentice Robert Mosher as his permanent on-site representative.[17] The final drawings were issued by Wright in March 1936 with work beginning on the bridge and main house in April.

The construction was plagued by conflicts between Wright, Kaufmann, and the contractor. Uncomfortable with what he saw as Wright's insufficient experience using reinforced concrete, Kaufmann had the architect's daring cantilever design reviewed by a firm of consulting engineers. Upon receiving their report, Wright took offense, immediately requesting that Kaufmann return his drawings and indicating that he was withdrawing from the project. Kaufmann relented to Wright's gambit and the engineer’s report was subsequently buried within a stone wall of the house.[17]

For the cantilevered floors, Wright and his team used upside-down T-shaped beams integrated into a monolithic concrete slab which formed both the ceiling of the space below and provided resistance against compression. The contractor, Walter Hall, also an engineer, produced independent computations and argued for increasing the reinforcing steel in the first floor’s slab---Wright refused the suggestion. There was speculation over the years that the contractor quietly doubled the amount of reinforcement[18] versus Kaufmann's consulting engineers doubling the amount of steel specified by Wright.[17] During the process of restoration begun in 1995, it was confirmed that additional concrete reinforcement had been added.

In addition, the contractor did not build in a slight upward incline in the formwork for the cantilever to compensate for its settling and deflection. Once the formwork was removed, the cantilever developed a noticeable sag. Upon learning of the unapproved steel addition, Wright recalled Mosher.[19] With Kaufmann’s approval, the consulting engineers had a supporting wall installed under the main supporting beam for the west terrace. When Wright discovered it on a site visit, he had Mosher discreetly remove the top course of stones. When Kaufmann later confessed to what had been done, Wright showed him what Mosher had done and pointed out that the cantilever had held up for the past month under test loads without the wall’s support.[20]

The main house was completed in 1938 and the guest house was completed the following year.[21]

Cost[]

The original estimated cost for building Fallingwater was $35,000. The final cost for the home and guest house was $155,000,[22][23][24] which included $75,000 for the house; $22,000 for finishings and furnishings; $50,000 for the guest house, garage and servants' quarters; and an $8,000 architect's fee. From 1938 through 1941, more than $22,000 was spent on additional details and for changes in the hardware and lighting.[25]

The total cost of $155,000, adjusted for inflation, is equivalent to about $2.9 million in 2020. The cost of the house's restoration in 2001 was estimated to be $11.5 million (approximately $16.8 million in 2020).[26]

Usage[]

Fallingwater was the family's weekend home from 1937 until 1963, when Edgar Kaufmann Jr. donated the property to the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.[23] The family retreated to Fallingwater on weekends to escape the heat and smoke of industrial Pittsburgh. Liliane enjoyed swimming in the nude and collecting modern art, especially the works of Diego Rivera, who was a guest at the country house.[27]

Kaufmann Jr. said, "[Wright] understood that people were creatures of nature, hence an architecture which conformed to nature would conform to what was basic in people. For example, although all of Falling Water [sic] is opened by broad bands of windows, people inside are sheltered as in a deep cave, secure in the sense of the hill behind them."[28]

Design[]

Fallingwater stands as one of Wright's greatest masterpieces both for its dynamism and for its integration with its striking natural surroundings. Fallingwater has been described as an architectural tour de force of Wright's organic architecture.[29] Wright's passion for Japanese architecture was strongly reflected in the design of Fallingwater, particularly in the importance of interpenetrating exterior and interior spaces and the strong emphasis placed on harmony between man and nature. Contemporary Japanese architect Tadao Ando has said of the house:

I think Wright learned the most important aspect of architecture, the treatment of space, from Japanese architecture. When I visited Fallingwater in Pennsylvania, I found that same sensibility of space. But there was the additional sounds of nature that appealed to me.[30]

The organically designed private residence was intended to be a nature retreat for its owners. The house is well-known for its connection to the site. It is built on top of an active waterfall that flows beneath the house.

The fireplace hearth in the living room integrates boulders found on the site and upon which the house was built—a ledge rock which protrudes up to a foot through the living room floor was left in place to link the outside with the inside. Wright had initially intended that the ledge be cut flush with the floor but this had been one of the family's favorite sunning spots, so Kaufmann suggested that it be left as it was.[citation needed] The stone floors are waxed while the hearth is left plain, giving the impression of dry rocks protruding from a stream.

Integration with the setting extends even to small details. For example, where glass meets stone walls no metal frame is used; rather, the glass and its horizontal dividers were run into a caulked recess in the stonework so that the stone walls appear uninterrupted by glazing. From the cantilevered living room, a stairway leads directly down to the stream below, and in a connecting space which connects the main house with the guest and servant level, a natural spring drips water inside, which is then channeled back out. Bedrooms are small, some with low ceilings to encourage people outward toward the open social areas, decks, and outdoors.

Bear Run and the sound of its water permeate the house, especially during the spring when the snow is melting, and locally quarried stone walls and cantilevered terraces resembling the nearby rock formations are meant to be in harmony. The design incorporates broad expanses of windows and balconies which reach out into their surroundings. In conformance with Wright's views, the main entry door is away from the falls.

On the hillside above the main house stands a four-bay carport, servants' quarters, and a guest house. These attached outbuildings were built two years later using the same quality of materials and attention to detail as the main house. The guest quarters feature a spring-fed swimming pool which overflows and drains to the river below.

Wright had initially planned to have the house blend into its natural settings in rural Pennsylvania.[31] In doing so, he limited his palette to two colors, a light ochre for the concrete and his signature Cherokee red for the steel.[32]

After Fallingwater was deeded to the public, three carport bays were enclosed at the direction of Kaufmann Jr. to be used by museum visitors to view a presentation at the end of their guided tours on the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy (to which the home was entrusted). Kaufmann Jr. designed its interior himself to specifications found in other Fallingwater interiors by Wright.

A model of the house was featured at the Museum of Modern Art in 2009.[33]

Western Pennsylvania Conservancy[]

After his father’s death in 1955, Kaufmann Jr. inherited Fallingwater, continuing to use it as a weekend retreat until the early 1960s. Increasingly concerned with ensuring Fallingwater’s preservation and following his father’s wishes, he entrusted the home and approximately 1,500 acres of land to the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy in tribute to his parents.[34] He guided the organization’s thinking about Fallingwater’s administration, care, and educational programming and was a frequent visitor as guided tours began in 1964. Kaufmann’s partner, architect and designer Paul Mayén, also contributed to the legacy of Fallingwater with a design for the visitor center, completed in 1981.[35] The house attracts more than 160,000 visitors from around the world each year.[21][36]

Preservation at Fallingwater[]

Fallingwater had shown signs of deterioration over the past 80 years due in large part to its exposure to humidity and sunlight. The severe freeze-thaw conditions of southwest Pennsylvania and water infiltration also affect the structural materials.[37] Because of these conditions, a thorough cleaning of the exterior stone walls is performed periodically.

Fallingwater’s six bathrooms are lined with cork tiles. When used as a flooring material, the cork tiles were hand-waxed, giving them a shiny finish that supplemented their natural ability to repel water. Over time the cork has begun to show water damage, requiring The Conservancy to make frequent repairs.[38]

In addition, Fallingwater's structural system includes a series of very bold reinforced concrete cantilevered balconies. Pronounced deflection of the concrete cantilevers was noticed as soon as the formwork was removed during construction. This deflection increased over time, eventually reaching 7 inches (180 mm) over a 15 foot (4.6 m) span.

In 1995, the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy commissioned a study of the site's structural integrity. Structural engineers analyzed the movement of the cantilevers over time and conducted radar analysis to locate and quantify the reinforcement. The data proved the contractor had indeed added reinforcement over Wright's plan; nevertheless, the cantilevers were still insufficiently reinforced. Both the concrete and its steel reinforcement were close to their failure limits. An architectural firm was hired to fix the problem[39] beginning with the installation of temporary girders in 1997.[37][40]

In 2002, the structure was repaired permanently using post-tensioning. The living room flagstone floor blocks were individually tagged and removed. Blocks were joined to the concrete cantilever beams and floor joists; high-strength steel cables were fed through the blocks and exterior concrete walls and tightened using jacks. The floors and walls were then restored, leaving Fallingwater’s interior and exterior appearance unchanged. Today, the cantilevers have sufficient support and the deflection has stopped.[41] The Conservancy continues to monitor movement in the cantilevers.

Depictions in popular culture[]

- Fallingwater inspired the fictional Vandamm residence at Mount Rushmore in the 1959 Alfred Hitchcock film North by Northwest.[42]

- Composer Michael Daugherty's 2013 concerto for violin and string orchestra, "Fallingwater", was inspired by the house.[43]

- The cover of Autechre's EP Envane traces and stylizes parts of the building.[44]

- Peter Blume's painting, The Rock, also commissioned by Liliane and Edgar Kaufmann, and now in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago depicts a construction scene reminiscent of the construction of Fallingwater.[45]

- Two characters in Neal Shusterman's Arc of a Scythe book series live at Fallingwater.[46]

- Episode 16 of the anime series Eureka Seven includes a replica of Fallingwater hidden in a cave.

- Fallingwater appears in a cartoon of the story "Amelia e la pietra pantarba" on Topolino #2043, the long-running Italian Disney magazine. The house of the witch is turned into Fallingwater by a spell before turning back to its normal appearance.

- The design is pastiched in the 1979 animated package film The Bugs Bunny/Road Runner Movie.

- The final chapter of science-fiction novel Endymion follows the characters visiting Fallingwater in the 31st century.

- Fallingwater is referenced in the song "Mamah Borthwick (A Sketch)" by singer Conor Oberst on his album "Salutations".

- Lego Architecture released a 811 piece construction model set of the building in 2009.

See also[]

- Kaufmann Desert House, another Kaufmann residence

- Kentuck Knob, another Wright-designed residence in the same area

- List of Frank Lloyd Wright works

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Fallingwater". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2008-06-24. Retrieved 2008-07-02.

- ^ "PHMC Historical Markers". Historical Marker Database. Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission. Archived from the original on December 7, 2013. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- ^ "Fallingwater". Western Pennsylvania Conservancy. Retrieved 2021-09-07.

- ^ "Usonian Architech". TIME magazine Jan. 17, 1938. 1938-01-17. Archived from the original on March 12, 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-27.

- ^ "Smithsonian Magazine — Travel — The Smithsonian Life List". Smithsonian magazine January 2008. Retrieved 2010-08-19.

- ^ "AIA 150" (PDF).

- ^ "The 20th-Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved July 7, 2019.

- ^ McCarter, Robert (2001). "Wright, Frank Lloyd". In Boyer, Paul S. (ed.). The Oxford Companion to United States History. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "The Kaufmann Family – Fallingwater". Fallingwater. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Toker, F. (2003). Fallingwater Rising: Frank Lloyd Wright, E. J. Kaufmann, and America's most extraordinary house. New York: Knopf. ISBN 1400040264.

- ^ Hoffmann, Donald (1993). Frank Lloyd Wright's Fallingwater: The House and Its History (2 ed.). New York: Dover Publications Inc. pp. 11–25.

- ^ Tafel, Edgar (1979). Apprentice to genius: Years with Frank Lloyd Wright. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0070628151.

- ^ "Frank Lloyd Wright, Fallingwater". Khan Academy.

- ^ "[W]hy did the client say that he expected to look from his house toward the waterfall rather than dwell above it?" Edgar Kaufmann Jr., Fallingwater: A Frank Lloyd Wright Country House, New York: Abbeville Press, p. 31. (ISBN 0-89659-662-1)

- ^ McCarter, page 7.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d McCarter, page 12.

- ^ Feldman, Gerard C. (2005). "Fallingwater Is No Longer Falling Archived 2010-02-15 at the Wayback Machine". Structure magazine (September): pp. 46–50.

- ^ McCarter, pages 12 and 13.

- ^ McCarter, pages 13.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Fallingwater Facts - Fallingwater". Fallingwater. Retrieved 2017-12-15.

- ^ McCarter, page 59.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Plushnick-Masti, Ramit (2007-09-27). "New Wright house in western Pa. completes trinity of work". Associated Press. Retrieved 2007-10-09.

- ^ FROST, EDWARD (9 March 1986). "Frank Lloyd Wright's Masterpiece in Pennsylvania : Fallingwater--Where Man and Nature Live in Harmony" – via LA Times.

- ^ Hoffman, page 61

- ^ Lowry, Patricia (2001-12-08). "Restoration of drooping Fallingwater uncovers flaws amid genius". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "The Kaufmann Legacy". Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- ^ Curtis, William J. R. (1983). Modern Architecture Since 1900. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice-Hall.

- ^ "Fallingwater". The Columbia Encyclopedia. Columbia University Press.

- ^ "Tadao Ando, 1995 Laureate: Biography" (PDF). The Hyatt Foundation. 1995. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 August 2009. Retrieved 5 November 2009.

- ^ Mims, SK (1993). "Teacher Residency at Fallingwater". Experiencing Architecture. 45–46: 19–24.

- ^ "Fallingwater". Retrieved September 22, 2013.

- ^ "Frank Lloyd Wright. Fallingwater, Edgar J. Kaufmann House, Mill Run, Pennsylvania. 1934-37 | MoMA". www.moma.org. Retrieved 2018-07-29.

- ^ "Edgar J. Kaufmann Charitable Fund | The Pittsburgh Foundation". pittsburghfoundation.org. Retrieved 2017-12-21.

- ^ "Behind Fallingwater: How Pa. became home to one of Frank Lloyd Wright's greatest works". PennLive.com. Retrieved 2017-12-21.

- ^ "The Kaufmann Family - Fallingwater". Fallingwater. Retrieved 2017-12-15.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Preservation History - Fallingwater". Fallingwater. Retrieved 2017-12-15.

- ^ "Preservation History - Fallingwater". Fallingwater. Retrieved 2017-12-21.

- ^ Saffron, Inga, To keep Fallingwater from falling down, Philadelphia Inquirer Magazine, September 8, 2002, pp. 13-15

- ^ Silman, Robert and John Matteo (2001-07-01). "Repair and Retrofit: Is Falling Water Falling Down?" (PDF). Structure Magazine. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-09-20.

- ^ Meek, Tyler. "Fallingwater: Restoration and Structural Reinforcement". Retrieved 18 October 2011. Archived 9 July 2012.

- ^ "The top houses from the movies". Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2012-05-02.

- ^ "From the Stage: Michael Daugherty's Fallingwater – November 2013", Retrieved August 27 2014.

- ^ "Chiastic Slide". The Designers Republic.

- ^ "The Rock". The Art Institute of Chicago. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- ^ Shusterman, Neal (2016-11-22). Scythe. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781442472426.

- Storrer, William Allin. The Frank Lloyd Wright Companion. University Of Chicago Press, 2006, ISBN 0-226-77621-2 (S.230)

Bibliography[]

- Trapp, Frank (1987). Peter Blume. Rizzoli, New York.

- Hoffmann, Donald (1993). Frank Lloyd Wright's Fallingwater: The House and Its History (2nd ed.). Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-27430-6.

- Brand, Stewart (1995). How Buildings Learn: What Happens After They're Built. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-013996-6.

- McCarter, Robert (2002). Fallingwater Aid (Architecture in Detail). Phaidon Press. ISBN 0-7148-4213-3.

Further reading[]

- Donald Hoffman, Fallingwater: The House and Its History (Dover Publications, 1993)

- Edgar Kaufmann Jr., Fallingwater: A Frank Lloyd Wright Country House (Abbeville Press 1986)

- Robert McCarter, Fallingwater Aid (Architecture in Detail) (Phaidon Press 2002)

- Franklin Toker, Fallingwater Rising: Frank Lloyd Wright, E. J. Kaufmann, and America's Most Extraordinary House (Knopf, 2005)

- Lynda S. Waggoner and the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy, Fallingwater: Frank Lloyd Wright's Romance With Nature (Universe Publishing 1996)

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fallingwater. |

- Frank Lloyd Wright buildings

- Houses in Fayette County, Pennsylvania

- Historic house museums in Pennsylvania

- Museums in Fayette County, Pennsylvania

- Houses completed in 1939

- Houses on the National Register of Historic Places in Pennsylvania

- National Historic Landmarks in Pennsylvania

- Pennsylvania state historical marker significations

- Laurel Highlands

- Modernist architecture in Pennsylvania

- National Register of Historic Places in Fayette County, Pennsylvania

- Restored and conserved buildings

- 1939 establishments in Pennsylvania