Finding Nemo

| Finding Nemo | |

|---|---|

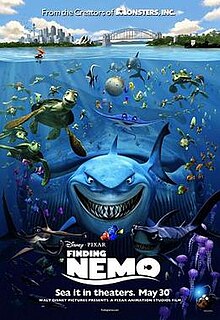

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Andrew Stanton |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by | Andrew Stanton |

| Produced by | Graham Walters |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography |

|

| Edited by | David Ian Salter |

| Music by | Thomas Newman |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Buena Vista Pictures Distribution |

Release date |

|

Running time | 100 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $94 million[1] |

| Box office | $940.3 million[1] |

Finding Nemo is a 2003 American computer-animated adventure film produced by Pixar Animation Studios and released by Walt Disney Pictures. Directed and co-written by Andrew Stanton with co-direction by Lee Unkrich, the screenplay was written by Bob Peterson, David Reynolds, and Stanton from a story by Stanton. The film stars the voices of Albert Brooks, Ellen DeGeneres, Alexander Gould, and Willem Dafoe. It tells the story of an overprotective clownfish named Marlin who, along with a regal blue tang named Dory, searches for his missing son Nemo. Along the way, Marlin learns to take risks and comes to terms with Nemo taking care of himself.

Released on May 30, 2003, Finding Nemo won the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature, the first Pixar film to do so. It was also nominated in three more categories, including Best Original Screenplay. Additionally, it became the highest-grossing animated film at the time of its release, and was the second-highest-grossing film of 2003, earning a total of $871 million worldwide by the end of its initial theatrical run.[2]

Finding Nemo is the best-selling DVD title of all time, with over 40 million copies sold as of 2006,[3] and was the highest-grossing G-rated film of all time before Pixar's own Toy Story 3 overtook it. The film was re-released in 3D in 2012. In 2008, the American Film Institute named it as the 10th greatest animated film ever made as part of their 10 Top 10 lists.[4] In a 2016 poll of international critics conducted by BBC, Finding Nemo was voted one of the 100 greatest motion pictures since 2000.[5] A spin-off sequel, Finding Dory, was released in June 2016.

Plot

Marlin is a clownfish who lives in an anemone in the Great Barrier Reef. His wife, Coral, and most of their eggs are killed in a barracuda attack. Only one damaged egg remains, which Marlin names Nemo.

Years later, Marlin is overprotective of Nemo. On Nemo's first day of school, Marlin embarrasses Nemo, and the two fight. While Marlin is talking to Nemo's teacher, Nemo defiantly approaches a nearby speedboat, where he is captured by a pair of scuba divers. Marlin pursues the boat in vain and meets Dory, a blue tang who suffers from acute short-term memory loss, who offers her help. The two encounter three sharks who've sworn to abstain from eating fish. Marlin discovers a diver's mask that fell from the boat; he accidentally hits Dory with it, giving her a nosebleed. The scent sends one of the sharks into a feeding frenzy, but they flee after accidentally setting off a ring of old naval mines, which knock Marlin and Dory unconscious.

Nemo is placed in an aquarium in a dentist's office in Sydney, Australia. He meets the "Tank Gang", including yellow tang Bubbles, starfish Peach, cleaner shrimp Jacques, blowfish Bloat, royal gramma Gurgle, and damselfish Deb, led by Gill, a Moorish idol. Nemo learns he is to be given to the dentist's niece, Darla, who has killed her previous fish. Gill devises a risky escape plan: Nemo, who can fit inside the aquarium's filter tube, will jam the filter with a pebble, forcing the dentist to put the fish into plastic bags while he cleans the tank, giving them the opportunity to roll out the window and into the harbor. Nemo attempts the maneuver, but fails and is almost killed.

Marlin and Dory wake up unharmed, but the mask falls into a deep trench. They descend after it and encounter an anglerfish which chases them. Dory memorizes the address written on the goggles, and they escape. Dory and Marlin receive directions from a school of moonfish, but Marlin disregards them to take what he believes is a safer route. They stumble into a forest of jellyfish, the stings of which knock them unconscious. They awaken in the East Australian Current with a group of sea turtles including Crush and his son, Squirt. Marlin tells them about his quest, and the story is relayed across the ocean to Sydney where a pelican, Nigel, tells the Tank Gang. Inspired by his father's bravery, Nemo makes another attempt to jam the filter and succeeds, and soon the aquarium is covered in green algae.

Marlin and Dory exit the East Australian Current and are consumed by a blue whale. Dory tries communicating with the whale, which expels them through its blowhole at Sydney Harbour. They meet Nigel, who helps the pair escape from a group of seagulls and takes them to the dentist's office. The dentist has installed a new high-tech filter, foiling the Tank Gang's escape. Darla arrives, but Nemo plays dead to save himself. Nigel causes a disturbance, terrifying Darla and throwing the office into chaos. Marlin, seeing Nemo's act, believes Nemo is dead. After the dentist throws Nigel out (along with Marlin and Dory), Gill helps Nemo escape through a drain that leads to the ocean.

Despondent, Marlin bids farewell to Dory and begins his journey home. Marlin's departure causes Dory to lose her memory. Nemo reaches the ocean and meets Dory, but she does not remember him. However, her memory returns when she reads the word "Sydney" on a drainpipe. Dory reunites Nemo with Marlin, but a fishing trawler captures her in a net along with a school of grouper. With his father's blessing, Nemo enters the net and he and Marlin instruct all of the fish to swim down. Their combined force breaks the boat's net, allowing them to escape. Marlin and Nemo reconcile.

After returning home to the reef, Marlin is more confident while Dory has remained friends with the sharks. Marlin and Dory see Nemo off as he goes to school.

At the dentist's, the filter has broken, and the gang, having been put in bags, have escaped into the harbor. Still stuck in the bags, they ponder what to do next.

Voice cast

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2016) |

- Albert Brooks as Marlin, a clownfish and Nemo's father.

- Ellen DeGeneres as Dory, a regal blue tang with short-term memory loss.

- Alexander Gould as Nemo, Marlin's only surviving son, who is excited about life and exploring the ocean, but gets captured and domesticated as a pet.

- Willem Dafoe as Gill, a disfigured moorish idol fish living in an aquarium in a dentist clinic, and the leader of the Tank Gang.

- Brad Garrett as Bloat, the aquarium's porcupinefish.

- Allison Janney as Peach, the aquarium's sea star.

- Stephen Root as Bubbles, the aquarium's yellow tang fish.

- Austin Pendleton as Gurgle, the aquarium's obsessive-compulsive royal gramma fish.

- Vicki Lewis as Deb/Flo, the aquarium's striped damselfish.

- Joe Ranft as Jacques, the aquarium's cleaner shrimp.

- Geoffrey Rush as Nigel, an Australian pelican, who often visits the dentist clinic and is friends with the aquarium fish.

- Andrew Stanton as Crush, a green sea turtle.

- Elizabeth Perkins as Coral, Marlin's wife and Nemo's mother.

- Nicholas Bird as Squirt, Crush's son.

- Bob Peterson as Mr. Ray, a spotted eagle ray and Nemo's schoolteacher.

- Barry Humphries as Bruce, a vegetarian great white shark, who fights his instinctive wills to eat innocent fish and is friends with Anchor and Chum.

- Eric Bana as Anchor, a hammerhead shark who is friends with Bruce and Chum.

- Bruce Spence as Chum, a mako shark who is friends with Bruce and Anchor.

- Bill Hunter as Dentist.

- LuLu Ebeling as Darla, the dentist's rambunctious young niece.

- Jordy Ranft as Tad, a butterfly fish fingerling and Nemo's school friend.

- Erica Beck as Pearl, a young flapjack octopus and Nemo's school friend.

- Erik Per Sullivan as Sheldon, a young seahorse, and Nemo's school friend.

- John Ratzenberger as the school of moonfish.

Production

The inspiration for Nemo sprang from multiple experiences, going back to director Andrew Stanton's childhood, when he loved going to the dentist to see the fish tank, assuming that the fish were from the ocean and wanted to go home.[7] In 1992, shortly after his son was born, he and his family took a trip to Six Flags Discovery Kingdom (which was called Marine World at the time). There, after seeing the shark tube and various exhibits, he felt that the underwater world could be done beautifully in computer animation.[8] Later, in 1997, he took his son for a walk in the park but realized that he was overprotecting him and lost an opportunity to have a father-son experience that day.[7]

In an interview with National Geographic magazine, Stanton said that the idea for the characters of Marlin and Nemo came from a photograph of two clownfish peeking out of an anemone:

It was so arresting. I had no idea what kind of fish they were, but I couldn't take my eyes off them. And as an entertainer, the fact that they were called clownfish—it was perfect. There's almost nothing more appealing than these little fish that want to play peekaboo with you.[9]

In addition, clownfish are colourful, but do not tend to come out of an anemone often. For a character who has to go on a dangerous journey, Stanton felt a clownfish was the perfect type of fish for the character.[7] Pre-production of the film began in early 1997. Stanton began writing the screenplay during the post-production of A Bug's Life. As a result, Finding Nemo began production with a complete screenplay, something that co-director Lee Unkrich called "very unusual for an animated film".[7] The artists took scuba diving lessons to study the coral reef.[7]

Stanton originally planned to use flashbacks to reveal how Coral died but realized that by the end of the film there would be nothing to reveal, deciding to show how she died at the beginning of the movie.[7] The character of Gill also was different from the character seen in the final film. In a scene that was eventually deleted, Gill tells Nemo that he's from a place called Bad Luck Bay and that he has brothers and sisters in order to impress the young clownfish, only for the latter to find out that he was lying by listening to a patient reading a children's storybook that shares exactly the same details.[7]

The casting of Albert Brooks, in Stanton's opinion, "saved" the film.[7] Brooks liked the idea of Marlin being this clownfish who isn't funny and recorded outtakes of telling very bad jokes.

The idea for the initiation sequence came from a story conference between Andrew Stanton and Bob Peterson while they were driving to record the actors. Although he originally envisioned the character of Dory as male, Stanton was inspired to cast Ellen DeGeneres when he watched an episode of Ellen in which he saw her "change the subject five times before finishing one sentence".[7] The pelican character named Gerald (who in the final film ends up swallowing and choking on Marlin and Dory) was originally a friend of Nigel. They were going to play against each other with Nigel being neat and fastidious and Gerald being scruffy and sloppy. The filmmakers could not find an appropriate scene for them that did not slow the pace of the picture, so Gerald's character was minimized.[7]

Stanton himself provided the voice of Crush the sea turtle. He originally did the voice for the film's story reel and assumed they would find an actor later. When Stanton's performance became popular in test screenings, he decided to keep his performance in the film. He recorded all his dialogue while lying on a sofa in Unkrich's office.[7] Crush's son Squirt was voiced by Nicholas Bird, the young son of fellow Pixar director Brad Bird. According to Stanton, the elder Bird was playing a tape recording of his young son around the Pixar studios one day. Stanton felt the voice was "this generation's Thumper" and immediately cast Nicholas.[7]

Megan Mullally was originally going to provide a voice in the film. According to Mullally, the producers were dissatisfied to learn that the voice of her character Karen Walker on the television show Will & Grace was not her natural speaking voice. The producers hired her anyway, and then strongly encouraged her to use her Karen Walker voice for the role. When Mullally refused, she was dismissed.[10]

To ensure that the movements of the fish in the film were believable, the animators took a crash course in fish biology and oceanography. They visited aquariums, went diving in Hawaii, and received in-house lectures from an ichthyologist.[11] As a result, Pixar's animator for Dory, Gini Cruz Santos, integrated "the fish movement, human movement, and facial expressions to make them look and feel like real characters."[12][13] Production designer Ralph Eggleston created pastel drawings to give the lighting crew led by Sharon Calahan ideas of how every scene in the film should be lit.[14]

The film was dedicated to Glenn McQueen, a Pixar animator who died of melanoma in October 2002.[15] Finding Nemo shares many plot elements with Pierrot the Clownfish,[16] a children's book published in 2002, but allegedly conceived in 1995. The author, Franck Le Calvez, sued Disney for infringement of his intellectual rights and to bar Finding Nemo merchandise in France. The judge ruled against him, citing the color differences between Pierrot and Nemo.[17]

Localization

In 2016, Disney Character Voices International's senior vice president Rick Dempsey, in collaboration with the Navajo Nation Museum, created a Navajo dubbing of the movie titled Nemo Há’déést’íí which was released in theaters March 18–24 of the same year.[18][19] The project was thought as a means to preserve Navajo language, teaching the language to kids through a Disney movie.[20] The studio held auditions on the reservation, but finding an age-appropriate native speaker to voice Nemo was hard, Dempsey said, as the majority of native Navajo speakers are over 40 years old.[19] The end credits version of the song Beyond the Sea, covered in the English version by Robbie Williams, was also adapted into Navajo, with Fall Out Boy's lead singer Patrick Stump performing it.[21] Finding Nemo was the second movie to receive a Navajo dubbing: in 2013, a Navajo version of Star Wars was created.[22]

Video game

A video game based on the film was released in 2003, for PC, Xbox, PlayStation 2, Nintendo GameCube, and Game Boy Advance. The goal of the game is to complete different levels under the roles of Nemo, Marlin or Dory. It includes cut scenes from the movie, and each clip is based on a level. It was also the last Pixar game developed by Traveller's Tales. Upon release, the game received mixed reviews.[23][24][25][26][27][28] A Game Boy Advance sequel, titled Finding Nemo: The Continuing Adventures, was released in 2004.[29]

Reception

Box office

During its original theatrical run, Finding Nemo grossed $339.7 million in North America, and $531.3 million in other countries, for a worldwide total of $871.0 million.[2] It is the 12th highest-grossing animated film, and the second-highest-grossing film of 2003, behind The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King.[30] Worldwide, it was the highest-grossing Pixar film, up until 2010, when Toy Story 3 surpassed it.[31] The film sold an estimated 56.4 million tickets in the US in its initial theatrical run.[32]

In North America, Finding Nemo set an opening weekend record for an animated feature, making $70.3 million (first surpassed by Shrek 2) and ended up spending 11 weeks in the top 10 domestically (including 7 weeks in the top 5), remaining there until August 14.[33] It became the highest-grossing animated film in North America ($339.7 million), outside North America ($531.3 million), and worldwide ($871.0 million), in all three occasions out-grossing The Lion King.[34] In North America, it was surpassed by both Shrek 2 in 2004 and Toy Story 3 in 2010.[35] Outside North America, it stands as the fifth-highest-grossing animated film. Worldwide, it now ranks fourth among animated films.[36]

The film had impressive box office runs in many international markets. In Japan, its highest-grossing market after North America, it grossed ¥11.2 billion ($102.4 million), becoming the highest-grossing foreign animated film in local currency (yen).[37] It has only been surpassed by Frozen (¥25.5 billion).[38] Following in biggest grosses are the U.K., Ireland and Malta, where it grossed £37.2 million ($67.1 million), France and the Maghreb region ($64.8 million), Germany ($53.9 million), and Spain ($29.5 million).[39]

3D re-release

After the success of the 3D re-release of The Lion King, Disney re-released Finding Nemo in 3D on September 14, 2012,[40] with a conversion cost estimated to be below $5 million.[41] For the opening weekend of its 3D re-release in North America, Finding Nemo grossed $16.7 million, debuting at the No. 2 spot behind Resident Evil: Retribution.[42] The film earned $41.1 million in North America and $28.2 million internationally, for a combined total of $69.3 million, and a cumulative worldwide total of $940.3 million.[1]

Critical response

The review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes reported a 99% approval rating, with a rating average of 8.70/10, based on 268 reviews. The site's consensus reads: "Breathtakingly lovely and grounded by the stellar efforts of a well-chosen cast, Finding Nemo adds another beautifully crafted gem to Pixar's crown."[43] Another review aggregation website, Metacritic, which assigns a normalized rating out of 100 top reviews from mainstream critics, calculated a score of 90 out of 100, based on 38 reviews, indicating "universal acclaim."[44] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film a rare average grade of "A+" on an A+ to F scale.[45]

Roger Ebert gave the film four out of four stars, calling it "one of those rare movies where I wanted to sit in the front row and let the images wash out to the edges of my field of vision".[46] Ed Park of The Village Voice gave the film a positive review, saying "It's an ocean of eye candy that tastes fresh even in this ADD-addled era of SpongeBob SquarePants."[47] Mark Caro of the Chicago Tribune gave the film four out of four stars, saying "You connect to these sea creatures as you rarely do with humans in big-screen adventures. The result: a true sunken treasure."[48] Hazel-Dawn Dumpert of LA Weekly gave the film a positive review, saying "As gorgeous a film as Disney's ever put out, with astonishing qualities of light, movement, surface and color at the service of the best professional imaginations money can buy."[49] Jeff Strickler of the Star Tribune gave the film a positive review, saying it "proves that even when Pixar is not at the top of its game, it still produces better animation than some of its competitors on their best days."[49] Gene Seymour of Newsday gave the film three-and-a-half stars out of four, saying "The underwater backdrops take your breath away. No, really. They're so lifelike, you almost feel like holding your breath while watching."[49] Rene Rodriguez of the Miami Herald gave the film four out of four stars, saying "Parental anxiety may not be the kind of stuff children's films are usually made of, but this perfectly enchanting movie knows how to cater to its kiddie audience without condescending to them."[50]

Kenneth Turan of the Los Angeles Times gave the film three-and-a-half out of five, saying "The best break of all is that Pixar's traditionally untethered imagination can't be kept under wraps forever, and "Nemo" erupts with sea creatures that showcase Stanton and company's gift for character and peerless eye for skewering contemporary culture."[51] Stephen Holden of The New York Times gave the film four out of five stars, saying "Visual imagination and sophisticated wit raise Finding Nemo to a level just below the peaks of Pixar's Toy Story movies and Monsters, Inc.."[52] Terry Lawson of the Detroit Free Press gave the film three out of four, saying "As we now expect from Pixar, even the supporting fish in "Finding Nemo" are more developed as characters than any human in the Mission: Impossible movies."[53] Claudia Puig of USA Today gave the film three and half out of four, saying "Finding Nemo is an undersea treasure. The most gorgeous of all the Pixar films—which include Toy Story 1 and 2, A Bug's Life and Monsters, Inc.—Nemo treats family audiences to a sweet, resonant story and breathtaking visuals. It may lack Monsters, Inc.'s clever humor, but kids will identify with the spunky sea fish Nemo, and adults will relate to Marlin, Nemo's devoted dad."[54] Bruce Westbrook of the Houston Chronicle gave the film an A-, saying "Finding Nemo lives up to Pixar's high standards for wildly creative visuals, clever comedy, solid characters and an involving story."[55] Tom Long of The Detroit News gave the film an A-, saying "A simple test of humanity: If you don't laugh aloud while watching it, you've got a battery not a heart."[49]

Lou Lumenick of the New York Post gave the film four out of four, saying "A dazzling, computer-animated fish tale with a funny, touching script and wonderful voice performances that make it an unqualified treat for all ages."[49] Moira MacDonald of The Seattle Times gave the film four out of four, saying "Enchanting; written with an effortless blend of sweetness and silliness, and animated with such rainbow-hued beauty, you may find yourself wanting to freeze-frame it."[49] Daphne Gordon of the Toronto Star gave the film four out of five, saying "One of the strongest releases from Disney in years, thanks to the work of Andrew Stanton, possibly one of the most successful directors you've never heard of."[49] Ty Burr of The Boston Globe gave the film three and a half out of four, saying "Finding Nemo isn't quite up there with the company's finest work—there's finally a sense of formula setting in—but it's hands down the best family film since Monsters, Inc."[49] C.W. Nevius of The San Francisco Chronicle gave the film four out of four, saying "The visuals pop, the fish emote and the ocean comes alive. That's in the first two minutes. After that, they do some really cool stuff."[56] Ann Hornaday of The Washington Post gave the film a positive review, saying "Finding Nemo will engross kids with its absorbing story, brightly drawn characters and lively action, and grown-ups will be equally entertained by the film's subtle humor and the sophistication of its visuals."[49] David Ansen of Newsweek gave the film a positive review, saying "A visual marvel, every frame packed to the gills with clever details, Finding Nemo is the best big-studio release so far this year."[57]

Richard Corliss of Time gave the film a positive review, saying "Nemo, with its ravishing underwater fantasia, manages to trump the design glamour of earlier Pixar films."[58] Lisa Schwarzbaum of Entertainment Weekly gave the film an A, saying "In this seamless blending of technical brilliance and storytelling verve, the Pixar team has made something as marvelously soulful and innately, fluidly American as jazz."[59] Carrie Rickey of The Philadelphia Inquirer gave the film three out of four, saying "As eye-popping as Nemo's peepers and as eccentric as this little fish with asymmetrical fins."[49] David Germain of the Associated Press gave the film a positive review, saying "Finding Nemo is laced with smart humor and clever gags, and buoyed by another cheery story of mismatched buddies: a pair of fish voiced by Albert Brooks and Ellen DeGeneres."[60] Anthony Lane of The New Yorker gave the film a positive review, saying "The latest flood of wizardry from Pixar, whose productions, from Toy Story onward, have lent an indispensable vigor and wit to the sagging art of mainstream animation."[61] The 3D re-release prompted a retrospective on the film nine years after its initial release. Stephen Whitty of The Star-Ledger described it as "a genuinely funny and touching film that, in less than a decade, has established itself as a timeless classic."[62] On the 3D re-release, Lisa Schwarzbaum of Entertainment Weekly wrote that its emotional power was deepened by "the dimensionality of the oceanic deep" where "the spatial mysteries of watery currents and floating worlds are exactly where 3D explorers were born to boldly go".[63]

Accolades

Finding Nemo won the Academy Award and Saturn Award for Best Animated Film.[64] It also won the award for Best Animated Film at the Kansas City Film Critics Circle Awards, the Las Vegas Film Critics Society Awards, the National Board of Review Awards, the Online Film Critics Society Awards, and the Toronto Film Critics Association Awards.[65] The film received many other awards, including: Kids Choice Awards for Favorite Movie and Favorite Voice from an Animated Movie (Ellen DeGeneres), and the Saturn Award for Best Supporting Actress (Ellen DeGeneres).[65]

The film was also nominated for two Chicago Film Critics Association Awards, for Best Picture and Best Supporting Actress (Ellen DeGeneres), a Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy, and two MTV Movie Awards, for Best Movie and Best Comedic Performance (Ellen DeGeneres).[65]

In June 2008, the American Film Institute revealed its "Ten Top Ten", the best 10 films in 10 "classic" American film genres, after polling over 1,500 people from the creative community. Finding Nemo was acknowledged as the 10th best film in the animation genre.[4] It was the most recently released film among all 10 lists, and one of only three movies made after the year 2000 (the others being The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring and Shrek).[66]

American Film Institute recognition:

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies – Nominated[66]

- AFI's 10 Top 10 – No. 10 Animated film[4]

Environmental concerns and consequences

The film's use of clownfish prompted mass purchase of the fish breed as pets in the United States, even though the story portrayed the use of fish as pets negatively and suggested that saltwater aquariums are notably tricky and expensive to maintain.[67] The demand for clownfish was supplied by large-scale harvesting of tropical fish in regions like Vanuatu.[68] The Australian Tourism Commission (ATC) launched several marketing campaigns in China and the United States to improve tourism in Australia, many of them utilizing Finding Nemo clips.[69][70] Queensland used Finding Nemo to draw tourists to promote itself to vacationers.[71] According to National Geographic, "Ironically, Finding Nemo, a movie about the anguish of a captured clownfish, caused home-aquarium demand for them to triple."[72]

The reaction to the film by the general public has led to environmental devastation for the clownfish, and has provoked an outcry from several environmental protection agencies, including the Marine Aquarium Council, Australia. The demand for tropical fish skyrocketed after the film's release, causing reef species decimation in Vanuatu and several other reef areas.[73] After seeing the film, some aquarium owners released their pet fish into the ocean, but failed to release them into the correct oceanic habitat, which introduced species that are harmful to the indigenous environment, a practice that is harming reefs worldwide.[74][75]

Home media

Finding Nemo was released on VHS and DVD on November 4, 2003.[citation needed] The DVD release included an original short film, Exploring the Reef, and the short animated film, Knick Knack (1989).[76] It would go on to become the best-selling DVD of its time, selling over 2 million units in its first two weeks of release.[77]

The film was then released on both Blu-ray 3D and Blu-ray on December 4, 2012, with both a 3-disc and a 5-disc set.[78] In 2019, Finding Nemo was released on 4K Ultra HD Blu-ray.[79][80]

Soundtrack

Finding Nemo was the first Pixar film not to be scored by Randy Newman. The original soundtrack album, Finding Nemo, was scored by Thomas Newman, his cousin, and released on May 20, 2003.[81][82] The score was nominated for the Academy Award for Original Score, losing to The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King.[83]

Theme park attractions

Finding Nemo has inspired numerous attractions and properties at Disney Parks around the world, including: Turtle Talk with Crush, which opened in 2004 at Epcot, 2005 in Disney California Adventure Park, 2008 in Hong Kong Disneyland, and 2009 in Tokyo DisneySea; Finding Nemo Submarine Voyage, which opened in 2007 in Disneyland Park; The Seas with Nemo & Friends, which opened in 2007 at Epcot; Finding Nemo – The Musical, which opened in 2007 in Disney's Animal Kingdom; and Crush's Coaster, which opened in 2007 at Walt Disney Studios Park.[84][85][86]

Sequel

A spin-off sequel[a] to this film was released in June 2016, titled Finding Dory.[93] It focuses on Dory having a journey to reunite with her parents (Diane Keaton and Eugene Levy).[88][94] Like the previous film, Finding Dory was a financial success and fared well with critics.[95][96]

See also

Notes

References

- ^ a b c d "Finding Nemo". Box Office Mojo. IMDb. Archived from the original on August 21, 2020. Retrieved June 18, 2021.

- ^ a b "Finding Nemo (2003)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on August 31, 2012.

- ^ Boone, Louis E.Contemporary Business 2006, Thomson South-Western, page 4 – ISBN 0-324-32089-2

- ^ a b c "Top 10 Animation". American Film Institute. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- ^ "The 21st Century's 100 greatest films". BBC. August 23, 2016. Retrieved December 16, 2016.

- ^ "Pixar Animation Studios". Pixar. Cast. Retrieved July 13, 2021. The Pixar webpage for Finding Nemo displays the full cast list and serves as a reference for the entire section.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Finding Nemo, 2004 DVD, commentary

- ^ The Pixar Story by Leslie Iwerks, 2007 documentary

- ^ Beautiful Friendship National Geographic magazine, January 2010

- ^ "Megan Mullally – Megan Mullally Dropped From Finding Nemo". WENN. Retrieved October 1, 2014.

- ^ Lovgren, Stefan. "For Finding Nemo, Animators Dove into Fish Study". National Geographic News. Retrieved October 30, 2012.

- ^ 31st Annual Annie Awards, 31st Annual Annie Award Nominees and Winners (2003). Retrieved June 12, 2014, "… Character Animation… Gini Santos Finding Nemo…"

- ^ Howell, Sean (October 23, 2009). "Profile of Gini Santos - Pixar Animator Brings Asian Flare and Female Perspective". Yahoo! Voices. Archived from the original on June 13, 2014. Retrieved April 27, 2017.

…Pixar … Finding Nemo, she integrates the fish movement, human movement, and facial expressions to make them look and feel like real characters…

- ^ Finding Nemo, 2004 DVD Disc 2, Making Nemo, documentary

- ^ Rizvi, Samad (December 24, 2010). "Remembering Glenn McQueen, 1960-2002". Pixar Times. Retrieved November 8, 2012.

- ^ Henley, Jon (February 24, 2004). "Nemo finds way to French court" – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ Aude Lagorce (December 3, 2004). "French Court Denies Disney Ban". Forbes. Retrieved September 30, 2012.

- ^ "'Nemo Há'déést'į́į́'". Navajo Times. March 10, 2016. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- ^ a b July 18, Jim Axelrod CBS News; 2015; Pm, 8:53. ""Finding Nemo" aims to help Navajo language stay afloat". www.cbsnews.com. Retrieved June 3, 2020.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- ^ "Navajo Version of 'Finding Nemo' Aims to Promote Language". YouTube.

- ^ "Making Movie Magic in Any Language". D23. December 16, 2016. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- ^ "Navajo the chosen one for new "Star Wars" dub". www.cbsnews.com. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- ^ "Aggregate score for GBA at GameRankings".

- ^ "Aggregate score for PS2 at Metacritic".

- ^ "PS2 review at GameSpot".

- ^ "Game Boy Advance review at GameSpy". Archived from the original on December 31, 2005.

- ^ "PS2 review at GameSpy".

- ^ "PS2 review at IGN".

- ^ Adams, David (September 16, 2004). "Shipping Nemo". IGN. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- ^ "Top Grossing Films of 2003". Boxofficemojo.com.

- ^ "Pixar". Boxofficemojo.com. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- ^ "Finding Nemo". Boxofficemojo.com.

- ^ "Weekend Box Office Results for May 30-June 1, 2003". Box Office Mojo. June 1, 2003. Retrieved January 11, 2014.

- ^ "Finding Nemo (2003)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved January 11, 2014.

- ^ "WORLDWIDE GROSSES". Boxofficemojo.com. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- ^ "Animation". Boxofficemojo.com. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- ^ Subers, Ray (August 29, 2010). "'Toy Story 3' Reaches $1 Billion". Box Office Mojo. Amazon.com. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ "歴代興収ベスト100". 歴代ランキング. Retrieved December 12, 2018.

- ^ "Box Office Mojo International". Boxofficemojo.com. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- ^ Smith, Grady (October 4, 2011). "'Beauty and the Beast,' 'The Little Mermaid,' 'Finding Nemo,' 'Monsters, Inc.' get 3-D re-releases". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved October 27, 2011.

- ^ Segers, Frank (September 16, 2012). "Foreign Box Office: 'Resident Evil: Retribution' Rules Overseas, Grossing $50 Million in 65 Markets". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ "Weekend Report: 'Resident Evil 5,' 'Nemo 3D' Lead Another Slow Weekend". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ "Finding Nemo". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- ^ "Finding Nemo". Metacritic. Red Ventures. Retrieved June 18, 2021.

- ^ "53 Movies With A+ CinemaScore Since 2000, From 'Remember the Titans' to 'Just Mercy' (Photos)". TheWrap. January 12, 2020. Retrieved March 2, 2020.

- ^ Roger Ebert (May 30, 2003). "Finding Nemo Review– rogerebert.com". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved October 1, 2014.

- ^ Ed Park (May 27, 2003). "Gods and Sea Monsters – Page 1 - Movies – New York". The Village Voice. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ^ Caro, Mark. "Metromix.com: Movie review: 'Finding Nemo'". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on February 17, 2004. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Finding Nemo – Movie Reviews". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ^ "Movie: Finding Nemo". Archived from the original on June 4, 2003. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ^ Turan, Kenneth (May 30, 2003). "Hook, line and sinker". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ^ Holden, Stephen (May 30, 2003). "Movie Review – Finding Nemo – FILM REVIEW; Vast Sea, Tiny Fish, Big Crisis". The New York Times. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ^ "Movie: Finding Nemo". Archived from the original on August 25, 2003. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ^ Puig, Claudia (May 29, 2003). "USATODAY.com – Sweet and funny 'Nemo' works just swimmingly". USA Today. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ^ "Finding Nemo". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on September 2005. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ^ C.W. Nevius (May 30, 2003). "Pixar splashes 'Finding Nemo' in a sea of colors". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ^ Ansen, David (June 1, 2003). "Freeing Nemo: A Whale Of A Tale". Newsweek. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (May 19, 2003). "Hook, Line and Thinker". TIME. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ^ Lisa Schwarzbaum (June 13, 2003). "FINDING NEMO Review | Movie Reviews and News". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ^ David Germain (May 29, 2003). "Miscellaneous: At the Movies - 'Finding Nemo' (05/29/03)". Southeast Missourian. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ^ Lane, Anthony. "Finding Nemo". The New Yorker. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ^ Whitty, Stephen (September 14, 2012). "Finding Nemo 3D review". The Star-Ledger. Retrieved October 2, 2012.

- ^ Schwarzbaum, Lisa (September 15, 2012). "Finding Nemo 3D". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved September 16, 2012.

- ^ "Finding Nemo - 2003 Academy Awards Profile". Boxofficemojo.com. May 30, 2003. Retrieved January 9, 2014.

- ^ a b c "Finding-Nemo – Cast, Crew, Director and Awards". The New York Times. 2014. Archived from the original on January 23, 2014. Retrieved January 9, 2014.

- ^ a b "AFI Crowns Top 10 Films in 10 Classic Genres". ComingSoon.net. American Film Institute. June 17, 2008. Retrieved August 18, 2008.

- ^ Jackson, Elizabeth (November 29, 2002). "Acquiring Nemo". The Business Report. Archived from the original on December 4, 2003. Retrieved November 10, 2006.

- ^ Corcoran, Mark (November 9, 2002). "Vanuatu – Saving Nemo". ABC Foreign Correspondent. Archived from the original on December 19, 2005. Retrieved October 23, 2006.

- ^ "Tourism authorities hope "Nemo" will lead Chinese tourists to Australia". China Daily. August 18, 2003. Archived from the original on October 7, 2003. Retrieved April 27, 2017.

- ^ Mitchell, Peter (November 3, 2002). "Nemo-led recovery hope". The Age. Melbourne, Australia. Retrieved October 23, 2006.

- ^ Dennis, Anthony (February 11, 2003). "Sydney ignores Nemo". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved October 23, 2006.

- ^ "Clown Anemonefish". Nat Geo Wild : Animals. National Geographic Society. May 10, 2011. Archived from the original on December 19, 2011. Retrieved December 19, 2011.

- ^ "Nemo: Leave him in the ocean, not in the lounge room". Oceans Enterprises. Archived from the original on September 29, 2009. Retrieved December 4, 2018.

- ^ Arthur, Charles (July 1, 2004). "'Finding Nemo' pets harm ocean ecology". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on June 1, 2008.

- ^ Brylske, Alex. "Revealing Nemo's True Colors". Dive Training Magazine.

- ^ "The No. 1 Film of the Year Becomes The No. 1 DVD on Nov. 4!; Walt Disney Pictures Presentation of a Pixar Animation Studios Film Finding Nemo". Business Wire. July 28, 2003. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- ^ 2003 Annual Report (Report). The Walt Disney Company. 2004.

- ^ "Finding Nemo Hitting 2D and 3D Blu-ray on December 4". ComingSoon.net. June 1, 2012.

- ^ "New Releases: Sept. 10, 2019". Media Play News. Archived from the original on October 25, 2021. Retrieved October 26, 2021.

- ^ Heller, Emily (March 3, 2020). "A bunch of Pixar movies, including Up and A Bug's Life, come to 4K Blu-ray". Polygon. Archived from the original on October 25, 2021. Retrieved October 26, 2021.

- ^ "Finding Nemo (An Original Soundtrack)". AllMusic. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ "iTunes – Music – Finding Nemo (An Original Soundtrack) by Thomas Newman". iTunes Store. May 20, 2003. Retrieved April 17, 2014.

- ^ "2003 Academy Awards Nominations and Winners by Category". Boxofficemojo.com. Retrieved April 17, 2014.

- ^ "The Seas with Nemo & Friends | Walt Disney World Resort". Disney. Retrieved January 11, 2014.

- ^ "Finding Nemo: Submarine Voyage at Disneyland". Themeparkinsider.com. January 6, 2014. Retrieved January 11, 2014.

- ^ "Finding Nemo-The Musical | Walt Disney World Resort". Disney. Retrieved January 11, 2014.

- ^ Shepherd, Jack (March 30, 2016). "Finding Dory: There's a The Wire reunion happening in Pixar's film". The Independent. Archived from the original on October 12, 2021. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ^ a b Tilly, Chris (March 31, 2016). "New Finding Dory Characters Unveiled". IGN. Archived from the original on October 12, 2021. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ^ Pond, Neil (June 17, 2016). "Finding Dory: The forgetful Little Blue Fish from 'Nemo' Makes a Splash of Her Own". Parade. Archived from the original on October 12, 2021. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (July 28, 2016). "Finding Dory review – Pixar sequel treads water". The Guardian. Archived from the original on October 12, 2021. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ^ Adams, Sam (June 17, 2016). "Film review: Is Finding Dory a worthy sequel?". BBC. Archived from the original on October 12, 2021. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ^ Macdonald, Moira (June 16, 2016). "Adorable Pixar sequel 'Finding Dory' swims into our hearts". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on October 12, 2021. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ^ Patten, Dominic (September 18, 2013). "Disney Shifts 'Maleficent', 'Good Dinosaur' & 'Finding Dory' Release Dates". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on October 12, 2021. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ^ Reilly, Nick (May 28, 2016). "Finding Dory could be the first Pixar film to include a lesbian couple". NME. Archived from the original on October 12, 2021. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ^ Doty, Meriah; Pressberg, Mark (September 1, 2016). "Why 'Finding Dory 2' Isn't Already Greenlit and 6 Other Lessons From Summer of Sequels". TheWrap. Archived from the original on October 12, 2021. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ^ "What Critics Are Saying About 'Finding Dory'". The Wall Street Journal. June 17, 2016. Archived from the original on October 12, 2021. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Finding Nemo. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Finding Nemo |

- Official website from Disney

- Official website from Pixar

- Finding Nemo at IMDb

- Finding Nemo at the TCM Movie Database

- Finding Nemo at AllMovie

- Finding Nemo at The Big Cartoon DataBase

- 2003 films

- English-language films

- Finding Nemo

- 2003 computer-animated films

- 2000s American animated films

- 3D animated films

- 3D re-releases

- American 3D films

- American computer-animated films

- American films

- Animated feature films

- Animated films about fish

- Best Animated Feature Academy Award winners

- Best Animated Feature Annie Award winners

- Best Animated Feature Broadcast Film Critics Association Award winners

- 2000s English-language films

- Films scored by Thomas Newman

- Films directed by Andrew Stanton

- Films set in Sydney

- Films with screenplays by Andrew Stanton

- Pixar animated films

- Walt Disney Pictures films

- Father and son films