A Bug's Life

| A Bug's Life | |

|---|---|

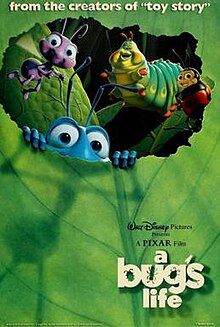

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | John Lasseter |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Sharon Calahan |

| Edited by | Lee Unkrich |

| Music by | Randy Newman |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Buena Vista Pictures Distribution |

Release date |

|

Running time | 95 minutes[2] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $120 million[1] |

| Box office | $363.3 million[1] |

A Bug's Life is a 1998 American computer-animated comedy film produced by Pixar Animation Studios for Walt Disney Pictures. It was the second film produced by Pixar. Directed by John Lasseter and co-directed and written by Andrew Stanton, the film involves a misfit ant, Flik, who is looking for "tough warriors" to save his colony from a protection racket run by Hopper's gang of grasshoppers. Unfortunately, the "warriors" he brings back turn out to be an inept troupe of Circus Bugs.

The film was initially inspired by Aesop's fable The Ant and the Grasshopper.[3][4] Production began shortly after the release of Toy Story in 1995. The screenplay was penned by Stanton and comedy writers Donald McEnery and Bob Shaw from a story by Lasseter, Stanton, and Ranft. The ants in the film were redesigned to be more appealing, and Pixar's animation unit employed technical innovations in computer animation. Randy Newman composed the music for the film. During production, a controversial public feud erupted between Steve Jobs and Lasseter of Pixar and DreamWorks co-founder Jeffrey Katzenberg due to the parallel production of his similar film Antz, which was released the same year.

The film was released on November 20, 1998, received positive reviews and grossed $363 million at the box office. It was the first film to be digitally transferred frame-by-frame and released on DVD, and has been released multiple times on home video.

Plot[]

A colony of ants, led by the elderly Queen and her daughter Princess Atta, lives in the middle of a seasonally dry creekbed on a small hill known as "Ant Island". Every summer, they are forced to give food to a gang of domineering grasshoppers, led by Hopper. One day, individualist and inventor Flik accidentally knocks the offering into the water with his latest invention, a grain harvester. Hopper demands twice as much food as compensation. When Flik earnestly suggests the ants enlist the help of bigger bugs to fight the grasshoppers, Atta sees it as a way to get rid of Flik and sends him off.

At the "bug city", which is a heap of trash under a trailer, Flik mistakes a troupe of Circus Bugs (who were recently dismissed by their greedy ringmaster, P.T. Flea) for the warrior bugs he seeks. The bugs, in turn, mistake Flik for a talent agent, and accept his offer to travel with him back to Ant Island. During a welcome ceremony upon their arrival, the Circus Bugs and Flik both discover their mutual misunderstandings. The Circus Bugs attempt to leave, but are pursued by a nearby bird; while fleeing, they rescue Dot, Atta's younger sister, from the bird, gaining the ants' respect. At Flik's request, they continue the ruse of being "warriors", so the troupe can continue to enjoy the hospitality of the ants. Hearing that Hopper fears birds inspires Flik to create a false bird to scare away the grasshoppers. Meanwhile, Hopper reminds his gang the ants outnumber them 100 to 1, and suspects that the ants will eventually rebel against him.

The ants finish constructing the fake bird. During the subsequent celebration, P.T. Flea arrives searching for his troupe to rehire them, revealing their secret. Outraged by Flik's deception, the ants exile him, and desperately attempt to gather food for a new offering to the grasshoppers. However, when Hopper returns to discover the mediocre offering, he takes over the island, and demands the ants' winter food supply, planning to execute the Queen afterwards. Overhearing the plan, Dot persuades Flik and the Circus Bugs to return to Ant Island.

After the Circus Bugs distract the grasshoppers long enough to rescue the Queen, Flik deploys the bird. It initially fools the grasshoppers, but P.T. Flea, who also mistakes it for a real bird, burns it, exposing it as a decoy. Hopper has Flik beaten in retaliation, saying that the ants are humble and lowly life forms who live to serve the grasshoppers. Flik asserts that Hopper actually fears the colony, because he has always known what they are capable of. This inspires the ants and the Circus Bugs to fight back against the grasshoppers, driving all but Hopper away.

The ants shove Hopper into P.T. Flea's circus cannon to shoot him off of the island, but rain suddenly begins to fall. In the ensuing chaos, Hopper frees himself from the cannon and abducts Flik. The Circus Bugs and Atta pursue, with the latter catching up to Hopper and rescuing Flik. Flik lures Hopper to the nest of the mother bird who attacked Dot earlier; thinking the bird is another fake, Hopper taunts her, until she grabs him and feeds him to her chicks.

With the enemies gone, Flik improves his inventions, along with the quality of life for Ant Island. He and Atta become a couple, and they send a few ants and Hopper's friendly brother Molt to help P.T. and the Circus Bugs on their new tour. Atta and Dot become the new Queen and Princess, respectively. The ants congratulate Flik as a hero, and bid a fond farewell to the circus troupe.

Voice cast[]

- Dave Foley as Flik, a brave, clever, but accident-prone ant

- Kevin Spacey as Hopper, the leader of the grasshoppers

- Julia Louis-Dreyfus as Princess Atta, a nervous queen-in-training of the ant colony

- Hayden Panettiere as Dot, Atta's younger sister

- Denis Leary as Francis, a male ladybug clown constantly mistaken for a female

- Joe Ranft as Heimlich, a large caterpillar clown with a German accent

- David Hyde Pierce as Slim, a walking stick clown who acts as a prop in the circus

- Jonathan Harris as Manny, a praying mantis who is the circus magician

- Madeline Kahn as Gypsy, Manny's gypsy moth wife and lovely assistant

- Bonnie Hunt as Rosie, a black widow spider and Dim's "tamer" in the circus

- Michael McShane as Tuck and Roll, two twin[5] pillbug brothers from Hungary and act as "human" cannonballs

- John Ratzenberger as P.T. Flea, a ringmaster of the circus

- Brad Garrett as Dim, a rhinoceros beetle that plays the "ferocious beast" in the circus

- Richard Kind as Molt, Hopper's dimwitted younger brother

- Phyllis Diller as The Queen, an elderly ant planning to soon retire

- Roddy McDowall as Mr. Soil, the ant colony's resident thespian

- Edie McClurg as Flora, the ant colony's doctor

- Alex Rocco as Thorny, Atta's grouchy assistant

- David Ossman as Cornelius, a very old ant whom the Queen flirts with

- David Lander as Thumper, Hopper's deranged "enforcer"

- Rodger Bumpass as Harry, a mosquito

- Ashley Tisdale as the leader of the Blueberry Scouts, a troop of ant children that Dot belongs to

- Jan Rabson and Carlos Alazraqui as Axel and Loco, a duo of grasshoppers from Hopper's gang

- Bob Bergen as Aphie, the Queen's pet aphid

Production[]

Development[]

During the summer of 1994, Pixar's story department began turning their thoughts to their next film.[6] The storyline for A Bug's Life originated from a lunchtime conversation between John Lasseter, Andrew Stanton, Pete Docter, and Joe Ranft, the studio's head story team; other films such as Monsters, Inc., Finding Nemo and WALL-E were also conceived at this lunch.[7] Lasseter and his story team had already been drawn to the idea of insects serving as characters. Like toys, insects were within the reach of computer animation back then, due to their relatively simple surfaces. Stanton and Ranft wondered whether they could find a starting point in Aesop's fable The Ant and the Grasshopper.[7] Walt Disney had produced his own version with a cheerier ending decades earlier in the 1934 short film The Grasshopper and the Ants. In addition, Walt Disney Feature Animation had considered producing a film in the late-1980s entitled Army Ants, that centered around a pacifist ant living in a militaristic colony, but this never fully materialized.[8]

As Stanton and Ranft discussed the adaptation, they rattled off scenarios and storylines springing from their premise.[7] Lasseter liked the idea and offered some suggestions. The concept simmered until early 1995, when the story team began work on the second film in earnest.[7] During an early test screening for Toy Story in San Rafael in June 1995, they pitched the film to Disney CEO Michael Eisner. Eisner thought the idea was fine and they submitted a treatment to Disney in early-July under the title Bugs.[7] Disney approved the treatment and gave notice on July 7 that it was exercising the option of a second film under the original 1991 agreement between Disney and Pixar.[9] Lasseter assigned the co-director job to Stanton; both worked well together and had similar sensibilities. Lasseter had realized that working on a computer-animated feature as a sole director was dangerous while the production of Toy Story was in process.[9] In addition, Lasseter believed that it would relieve stress and that the role would groom Stanton for having his own position as a lead director.[10]

Writing[]

In The Ant and the Grasshopper, a grasshopper squanders the spring and summer months on singing while the ants put food away for the winter; when winter comes, the hungry grasshopper begs the ants for food, but the ants turn him away.[7] Andrew Stanton and Joe Ranft hit on the notion that the grasshopper could just take the food.[7][11] After Stanton had completed a draft of the script, he came to doubt one of the story's main pillars – that the Circus Bugs that had come to the colony to cheat the ants would instead stay and fight.[10] He thought the Circus Bugs were unlikable characters as liars and that it was unrealistic for them to undergo a complete personality change. Also, no particularly good reason existed for Circus Bugs to stay with the ant colony during the second act.[12] Although the film was already far along, Stanton concluded that the story needed a different approach.[10]

Stanton took one of the early circus bug characters, Red the red ant, and changed him into the character Flik.[12] The Circus Bugs, no longer out to cheat the colony, would be embroiled in a comic misunderstanding as to why Flik was recruiting them. Lasseter agreed with this new approach, and comedy writers Donald McEnery and Bob Shaw spent a few months working on further polishing with Stanton.[13] The characters "Tuck and Roll" were inspired by a drawing that Stanton did of two bugs fighting when he was in the second grade.[11] Lasseter had come to envision the film as an epic in the tradition of David Lean's 1962 film Lawrence of Arabia.[12][14]

Casting[]

The voice cast was heavy with television sitcom stars of the time: Flik was voiced by Dave Foley (from NewsRadio), Princess Atta was voiced by Julia Louis-Dreyfus (from Seinfeld), Molt was voiced by Richard Kind (from Spin City), Slim was voiced by David Hyde Pierce (from Frasier) and Dim was voiced by Brad Garrett (from Everybody Loves Raymond). Joe Ranft, member of Pixar's story team, played Heimlich the caterpillar at the suggestion of Lasseter's wife, Nancy, who had heard him playing the character on a scratch vocal track.[15]

Jim Carrey was originally considered for the role of Flik before the role was later given to Dave Foley.

The casting of Hopper, the film's villain, proved problematic. Lasseter's top choice was Robert De Niro, who repeatedly turned the part down, as did a succession of other actors.[15] Kevin Spacey met John Lasseter at the 1995 Academy Awards and Lasseter asked Spacey if he would be interested in doing the voice of Hopper. Spacey was delighted and signed on immediately.[12]

A Bug's Life was the final film appearance of actor Roddy McDowall, who played Mr. Soil, before dying shortly before the film's theatrical release.[16]

Art design and animation[]

It was more difficult for animators during the production of A Bug's Life than that of Toy Story, as computers ran sluggishly due to the complexity of the character models. Lasseter and Stanton had two supervising animators to assist with directing and reviewing the animation: Rich Quade and Glenn McQueen.[3]The first sequence to be animated and rendered was the circus sequence that culminated with P.T. Flea's "Flaming Wall of Death". Lasseter placed this scene first in the pipeline because he believed it was "less likely to change".[17] Lasseter thought it would be useful to look at a view of the world from an insect's perspective. Two technicians obliged by creating a miniature video camera on Lego wheels, which they dubbed as the "Bugcam".[10][18] Fastened to the end of a stick, the Bugcam could roll through grass and other terrain and send back an insect's-eye outlook. Lasseter was intrigued by the way grass, leaves, and flower petals formed a translucent canopy, as if the insects were living under a stained-glass ceiling. The team also later sought inspiration from Microcosmos (1996), a French documentary on love and violence in the insect world.[10]

The transition from treatment to storyboards took on an extra layer of complexity due to the profusion of storylines. Where Toy Story focused heavily on Woody and Buzz, with the other toys serving mostly as sidekicks, A Bug's Life required in-depth storytelling for several major groups of characters.[13] Character design also presented a new challenge, in that the designers had to make ants appear likable. Although the animators and the art department studied insects more closely, natural realism would give way to the film's larger needs.[14] The team took out mandibles and designed the ants to stand upright, replacing their normal six legs with two arms and two legs. The grasshoppers, in contrast, received a pair of extra appendages to appear less attractive.[14] The story's scale also required software engineers to accommodate new demands. Among these was the need to handle shots with crowds of ants.[14] The film would include more than 400 such shots in the ant colony, some with as many as 800. It was impractical for animators to control them individually, but neither could the ants remain static for even a moment without appearing lifeless, or move identically. Bill Reeves, one of the film's two supervising technical directors, dealt with the quandary by leading the development of software for autonomous ants.[14] The animators would only animate four or five groups of about eight individual "universal ants". Each one of these "universal ants" would later be randomly distributed throughout the digital set. The program also allowed each ant to be automatically modified in subtle ways (e.g. different color of eye or skin, different heights, different weights, etc.). This ensured that no two ants were the same.[18] It was partly based on Reeves's invention of particle systems a decade and a half earlier, which had let animators use masses of self-guided particles to create effects like swirling dust and snow.[15]

The animators also employed subsurface scattering—developed by Pixar co-founder Edwin Catmull during his graduate student days at the University of Utah in the 1970s—to render surfaces in a more lifelike way. This would be the first time that subsurface scattering would be used in a Pixar film, and a small team at Pixar worked out the practical problems that kept it from working in animation. Catmull asked for a short film to test and showcase subsurface scattering and the result, Geri's Game (1997), was attached alongside A Bug's Life in its theatrical release.[19]

Feud between Pixar and DreamWorks[]

During the production of A Bug's Life, a public feud erupted between DreamWorks' Jeffrey Katzenberg, and Pixar's Steve Jobs and John Lasseter. Katzenberg, former chairman of Disney's film division, had left the company in a bitter feud with CEO Michael Eisner. In response, he formed DreamWorks SKG with Steven Spielberg and David Geffen and planned to rival Disney in animation.[20] After DreamWorks' acquisition of Pacific Data Images (PDI)—long Pixar's contemporary in computer animation—Lasseter and others at Pixar were dismayed to learn from the trade papers that PDI's first project at DreamWorks would be another ant film, to be called Antz.[21] By this time, Pixar's project was well known within the animation community.[22] Both Antz and A Bug's Life center on a young male ant, a drone with oddball tendencies that struggles to win a princess's hand by saving their society. Whereas A Bug's Life relied chiefly on visual gags, Antz was more verbal and revolved more around satire. The script of Antz was also heavy with adult references, whereas Pixar's film was more accessible to children.[23]

It was clear that Lasseter and Jobs believed that the idea was stolen by Katzenberg.[8][20] Katzenberg had stayed in touch with Lasseter after the acrimonious Disney split, often calling to check up. In October 1995, when Lasseter was overseeing postproduction work on Toy Story at the Universal lot's Technicolor facility in Universal City, where DreamWorks was also located, he called Katzenberg and dropped by with Stanton.[20][24] When Katzenberg asked what they were doing next, Lasseter described what would become A Bug's Life in detail. Lasseter respected Katzenberg's judgment and felt comfortable using him as a sounding board for creative ideas.[24] Lasseter had high hopes for Toy Story, and he was telling friends throughout the tight-knit computer-animation business to get cracking on their own films. "If this hits, it's going to be like space movies after Star Wars" for computer animation companies, he told various friends.[8] "I should have been wary," Lasseter later recalled. "Jeffrey kept asking questions about when it would be released."[20]

When the trades indicated production on Antz, Lasseter, feeling betrayed, called Katzenberg and asked him bluntly if it were true, who in turn asked him where he had heard the rumor. Lasseter asked again, and Katzenberg admitted it was true. Lasseter raised his voice and would not believe Katzenberg's story that a development director had pitched him the idea long ago. Katzenberg claimed Antz came from a 1991 story pitch by Tim Johnson that was related to Katzenberg in October 1994.[8] Another source gives Nina Jacobson, one of Katzenberg's executives, as the person responsible for the Antz pitch.[22] Lasseter, who normally did not use profane language, cursed at Katzenberg and hung up the phone.[25] Lasseter recalled that Katzenberg began explaining that Disney was "out to get him" and that he realized that he was just cannon fodder in Katzenberg's fight with Disney.[8][22] For his part, Katzenberg believed he was the victim of a conspiracy: Eisner had decided not to pay him his contract-required bonus, convincing Disney's board not to give him anything.[22] Katzenberg was further angered by the fact that Eisner scheduled Bugs to open the same week as The Prince of Egypt, which was then intended to be DreamWorks' first animated release.[22][25] Lasseter grimly relayed the news to Pixar employees but kept morale high. Privately, Lasseter told other Pixar executives that he and Stanton felt terribly let down by Katzenberg.[22]

Katzenberg moved the opening of Antz from spring 1999 to October 1998 to compete with Pixar's release.[22][26] David Price writes in his 2008 book The Pixar Touch that a rumor, "never confirmed", was that Katzenberg had given PDI "rich financial incentives to induce them to whatever it would take to have Antz ready first, despite Pixar's head start".[22][25] Jobs was furious and called Katzenberg and began yelling. Katzenberg made an offer: He would delay production of Antz if Jobs and Disney would move A Bug's Life so that it did not compete with The Prince of Egypt. Jobs believed it "a blatant extortion attempt" and would not go for it, explaining that there was nothing he could do to convince Disney to change the date.[8][25] Katzenberg casually responded that Jobs himself had taught him how to conduct similar business long ago, explaining that Jobs had come to Pixar's rescue by making the deal for Toy Story, as Pixar was near bankruptcy at that time.[15] "I was the one guy there for you back then, and now you're allowing them to use you to screw me," Katzenberg said.[25] He suggested that if Jobs wanted to, he could simply slow down production on A Bug's Life without telling Disney. If he did, Katzenberg said, he would put Antz on hold.[8] Lasseter also claimed Katzenberg had phoned him with the proposition, but Katzenberg denied these charges later.[17]

As the release dates for both films approached, Disney executives concluded that Pixar should keep silent on the DreamWorks battle. Regardless, Lasseter publicly dismissed Antz as a "schlock version" of A Bug's Life.[19] Lasseter, who claimed to have never seen Antz, told others that if DreamWorks and PDI had made the film about anything other than insects, he would have closed Pixar for the day so the entire company could go see it.[8][23] Jobs and Katzenberg would not back down and the rivaling ant films provoked a press frenzy. "The bad guys rarely win," Jobs told the Los Angeles Times. In response, DreamWorks' head of marketing Terry Press suggested, "Steve Jobs should take a pill."[25] Despite the successful box office performance of both Antz and A Bug's Life, tensions would remain high between Jobs and Katzenberg for many years. According to Jobs, Katzenberg came to Jobs after the success of Shrek (2001) and insisted he had never heard the pitch for A Bug's Life, reasoning that his settlement with Disney would have given him a share of the profits if that were so.[27] Although the contention left all parties estranged, Pixar and PDI employees kept up the old friendships that had arisen from spending a long time together in computer animation.[17]

Music[]

| A Bug's Life: An Original Walt Disney Records Soundtrack | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by Randy Newman | ||||

| Released | October 27, 1998 | |||

| Recorded | 1998 | |||

| Genre | Score | |||

| Length | 47:32 | |||

| Label | Walt Disney | |||

| Randy Newman chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Pixar soundtrack chronology | ||||

| ||||

The film's score was composed and conducted by Randy Newman. Walt Disney Records released the soundtrack on October 27, 1998.[28] The album's first track is a song called "The Time of Your Life" written and performed by Newman, while all the other 19 tracks are orchestral cues. Although the album was out of print physically in the United States during the 2000s, in June 2018 Universal Music Japan announced that a re-mastered edition would be released on October 3, 2018, along with other soundtrack albums from the Walt Disney Records pre-2018 catalogue. The album is also available for purchase on iTunes. The time duration is 47 minutes and 32 seconds.[29] Out of five stars, AllMusic,[28] Empire Online,[30] and Film Tracks rated the album three stars.[31] Movie Wave rated it four and a half.[32] The score won the Grammy Award for Best Instrumental Composition.[29]

Reception[]

Box office[]

A Bug's Life grossed approximately $33,258,052 on its opening weekend, ranking number 1 for that weekend.[33] It managed to retain its number 1 spot for two weeks.[34][35] The film grossed $162.8 million in its United States theatrical run, covering its estimated production costs of $120 million. The film made $200,460,294 in foreign countries, pushing its worldwide gross to $363.3 million, surpassing the competition from DreamWorks Animation's Antz.[1]

Critical response[]

On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the film has a rating of 92% based on 88 reviews and an average rating of 7.87/10. The site's critical consensus reads, "A Bug's Life is a rousing adventure that blends animated thrills with witty dialogue and memorable characters – and another smashing early success for Pixar."[36] Another review aggregator, Metacritic, gave the film a score of 77 out of 100 based on 23 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[37]

Todd McCarthy of Variety wrote, "Lasseter and Pixar broke new technical and aesthetic ground in the animation field with Toy Story, and here they surpass it in both scope and complexity of movement while telling a story that overlaps Antz in numerous ways."[38] James Berardinelli of ReelViews gave the film three and a half stars out of four, saying "A Bug's Life, like Toy Story, develops protagonists we can root for, and places them in the midst of a fast-moving, energetic adventure."[39] Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film three and a half stars out of four, saying "Will A Bug's Life suffer by coming out so soon after Antz? Not any more than one thriller hurts the chances for the next one. Antz may even help business for A Bug's Life by demonstrating how many dramatic and comedic possibilities can be found in an anthill."[40] Kenneth Turan of the Los Angeles Times gave the film four out of five stars, saying "What A Bug's Life demonstrates is that when it comes to bugs, the most fun ones to hang out with hang exclusively with the gang at Pixar."[41] Peter Stack of the San Francisco Chronicle gave the film four out of four stars, saying "A Bug's Life is one of the great movies – a triumph of storytelling and character development, and a whole new ballgame for computer animation. Pixar Animation Studios has raised the genre to an astonishing new level".[42]

Richard Corliss of Time wrote, "The plot matures handsomely; the characters neatly converge and combust; the gags pay off with emotional resonance."[43] Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly gave the film a B, saying "A Bug's Life may be the single most amazing film I've ever seen that I couldn't fall in love with."[44] Paul Clinton of CNN wrote, "A Bug's Life is a perfect movie for the holidays. It contains a great upbeat message ... it's wonderful to look at ... it's wildly inventive ... and it's entertaining for both adults and kids."[45] Michael Wilmington of the Chicago Tribune gave the film three and a half stars out of four, and compared the movie to "Akira Kurosawa's Seven Samurai (with a little of another art-film legend, Federico Fellini, tossed in)." where "As in Samurai, the colony here is plagued every year by the arrival of bandits."[46] On the contrary, Stephen Hunter of The Washington Post wrote, "Clever as it is, the film lacks charm. One problem: too many bugs. Second, bigger world for two purposes: to feed birds and to irk humans."[47]

Accolades[]

A Bug's Life won a number of awards and numerous nominations. The film won the Broadcast Film Critics Association Awards for Best Animated Film (tied with The Prince of Egypt) and Best Family Film, the Satellite Award for Best Animated Film and the Grammy Award for Best Instrumental Composition by Randy Newman. It was also nominated for the Academy Award for Best Original Musical or Comedy Score, the Golden Globe Award for Best Original Score and the BAFTA Award for Best Achievement in Special Visual Effects.[48] In 2008, the American Film Institute nominated this film for its Top 10 Animation Films list.[49]

Legacy[]

In the years since its release, A Bug's Life has been regarded by critics and fans to be a Pixar film that, in contrast to its successors, has become largely forgotten by audiences.[50][51][52] While recognised as solidifying Pixar's success, the film has been seen as the studio's sophomore slump in the wake of the critically-successful Toy Story,[50][51][53][54][55] and inhibited by being released directly before the equally-revered Toy Story 2.[50] Pixar's feud with Dreamworks as a result of Antz has also been regarded as a factor in A Bug's Life's legacy.[55][56]

Critics have generally ranked A Bug's Life to be one of Pixar's weaker releases;[51][54][55][57][58] while it has been seen as a "charming"[52][58] and "ambitious"[59] film with pioneering animation for its time,[50][51][59] others have described it as "adequate"[57] and appealing more to a younger demographic.[58] However, the film's characters, voice acting, and humor have received lasting praise.[51][52][53][54][59]

Home media[]

A Bug's Life was the first home video release to be entirely created using a digital transfer. Every frame of animation was converted from the film's computer data, as opposed to the standard analog film-to-videotape transfer process. This allowed for the film's DVD release to retain its original 2.35:1 widescreen format.[60] The DVD was released on April 20, 1999, alongside a VHS release which was presented in a standard 1.33:1 "fullscreen" format. The film's fullscreen transfer was performed by entirely "reframing" the film shot by shot; more than half of the film's footage was modified by Pixar animators to fit within the film's aspect ratio. Several characters and objects were moved closer together to avoid being cut out of frame.[60] The film's VHS release was the best-selling VHS in the United Kingdom, with 1.76 million units sold by the end of the year.[61] On August 1, 2000, these editions were rereleased on VHS and DVD under the Walt Disney Gold Classic Collection banner.[62]

On November 23, 1999, a 2-disc Collector's Edition DVD was released. This DVD was fully remastered in anamorphic widescreen and has substantial bonus features.[citation needed] This edition was re-released on May 27, 2003 to coincide with the release of Finding Nemo. This THX certified DVD release once again gives the option of viewing the film in widescreen or fullscreen.[63] The second disc features numerous bonus features, such as a set-top game and a Finding Nemo featurette.[64]

On May 19, 2009, the film was released on Blu-ray.[65] The film was released on 4K Blu-ray on March 3, 2020.[66]

Media and merchandise[]

Attached short film[]

The film's theatrical and video releases include Geri's Game, an Academy Award winning Pixar short made in 1997, a year before this film was released.[67]

Video game[]

A game, based on the film, was developed by Traveller's Tales and Tiertex Design Studios and released by Sony Computer Entertainment, Disney Interactive, THQ and Activision for various systems. The game's storyline was similar to the film's, with a few changes. However, unlike the film, the game received mixed reviews.[68] Aggregating review website GameRankings gave the Nintendo 64 version 54.40%,[69] the PlayStation version 51.90%[70] and the Game Boy Color version 36.63%.[71] GameSpot gave the PlayStation version a 2.7/10, concluding that it was "obvious that Disney was more interested in producing a $40 advertisement for its movie than in developing a playable game."[72] IGN gave the Nintendo 64 version a 6.8/10, praising the presentation and sound by stating "It was upbeat, cheery look and feel very much like the movie of the same name with cheery, happy tunes and strong sound effects but again criticised the gameplay by saying the controls were sluggish with stuttering framerate and tired gameplay mechanics".[73] while they gave the PlayStation version a 4/10, criticizing the gameplay as slow and awkward but praising the presentation as cinematic.[74]

Theme park attractions[]

Disney's Animal Kingdom includes the 3D show It's Tough to Be a Bug!, which also existed at Disney California Adventure from 2001 to 2018. The Disney California Adventure nighttime show World of Color features a segment that includes Heimlich, the caterpillar from the film.[75]

Former theme park attractions[]

From 2002 to 2018, A Bug's Land was a section of Disney California Adventure that was inspired by the film.

See also[]

- List of animated feature-length films

- List of Pixar films

- List of computer-animated films

- List of Disney animated films based on fairy tales

- List of films featuring insects

References[]

- ^ a b c d "A Bug's Life (1998)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on September 15, 2010. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ "A Bug's Life". bbfc.co.uk. British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on March 2, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ a b Maslin, Janet (2016). "A Bug's Life (1998)". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 2, 2016. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ^ "A Bug's Life – The Tale". pixar.com. Pixar. Archived from the original on December 5, 2010. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- ^ Sterngold, James (December 4, 1998). "At the Movies; Bug's Word: Yaddanyafoo". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 29, 2014. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

Tuck is older by a few milliseconds,...

- ^ Price, p. 157

- ^ a b c d e f g Price, p. 158

- ^ a b c d e f g h Burrows, Peter (November 23, 1998). "Antz vs. Bugs". Business Week. Archived from the original on November 28, 1999. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- ^ a b Price, p. 159

- ^ a b c d e Price, p. 160

- ^ a b Pixar Animation Studios, official website, feature films, A Bugs Life, The inspiration

- ^ a b c d A Bugs Life, DVD Commentary

- ^ a b Price, p. 161

- ^ a b c d e Price, p. 162

- ^ a b c d Price, p. 163

- ^ Wilmington, Michael (November 25, 1998). "'A Bug's Life". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on January 4, 2018. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

The players—whose colorful members include Madeline Kahn as Gypsy the moth, Michael McShane as the Hungarian pill bug brothers Tuck & Roll and, in his farewell appearance, Roddy McDowall as the grandfatherly Mr. Soil—all help make "Bug's Life" special.

- ^ a b c Price, p. 172

- ^ a b A Bugs Life, DVD Behind the Scenes

- ^ a b Price, p. 173

- ^ a b c d Isaacson, Walter (2011). Steve Jobs. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 307. ISBN 978-1-4516-4853-9.

- ^ Price, p. 170

- ^ a b c d e f g h Price, p. 171

- ^ a b Price, p. 174

- ^ a b Price, p. 169

- ^ a b c d e f Isaacson, Walter (2011). Steve Jobs. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 308. ISBN 978-1-4516-4853-9.

- ^ "Of Ants, Bugs, and Rug Rats: The Story of Dueling Bug Movies". Associated Press. October 2, 1998. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved March 4, 2010.

- ^ Isaacson, Walter (2011). Steve Jobs. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 309. ISBN 978-1-4516-4853-9.

- ^ a b "AllMusic". AllMusic. Archived from the original on February 15, 2015. Retrieved October 9, 2014.

- ^ a b "iTunes Music – A Bug's Life (An Original Walt Disney Records Soundtrack) by Randy Newman". iTunes Store. October 23, 2001. Archived from the original on November 6, 2013. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ "Empire's A Bug's Life Soundtrack Review". Empire. Archived from the original on October 15, 2014. Retrieved October 9, 2014.

- ^ "Filmtracks". Archived from the original on October 28, 2014. Retrieved October 9, 2014.

- ^ "Movie Wave". Archived from the original on February 15, 2015. Retrieved October 9, 2014.

- ^ "Weekend Box Office Results for November 27–29, 1998". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on July 12, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ "Weekend Box Office Results for December 4–6, 1998". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on October 21, 2013. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ "Weekend Box Office Results for December 11–13, 1998". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on October 21, 2013. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ "A Bug's Life Movie Reviews, Pictures". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- ^ "A Bug's Life Reviews, Ratings, and more at Metacritic". Metacritic. Archived from the original on July 13, 2018. Retrieved July 22, 2011.

- ^ Todd McCarthy (November 29, 1998). "A Bug's Life". Variety. Archived from the original on March 20, 2018. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ "Reelviews Movie Reviews". Reelviews.net. November 25, 1998. Archived from the original on March 27, 2019. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (November 25, 1998). "A Bug's Life Movie Review & Film Summary (1998)". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on May 7, 2013. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ "A Bug's Life – Movie Reviews". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on October 27, 2013. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ Peter Stack (November 25, 1998). ""Bug's" Has Legs / Cute insect adventure a visual delight". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on October 21, 2013. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (November 30, 1998). "Cinema: Bugs Funny". Time. Archived from the original on July 20, 2014. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ Owen Gleiberman (November 20, 1998). "A Bug's Life Review | Movie Reviews and News". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on October 21, 2013. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ "Review: 'A Bug's Life' hits a bulls-eye – November 20, 1998". CNN. November 20, 1998. Archived from the original on October 22, 2013. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ Wilmington, Michael (November 25, 1998). "Movie Review: 'A Bug's Life Disney's Venture Into The Insect World Squashes 'Antz' – November 25, 1998". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on May 18, 2014. Retrieved November 2, 2013.

- ^ "'A Bug's Life' (G)". The Washington Post. November 25, 1998. Archived from the original on October 3, 2018. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ "A-Bug-s-Life – Cast, Crew, Director and Awards". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. 2014. Archived from the original on January 24, 2014. Retrieved January 13, 2014.

- ^ "AFI's 10 Top 10 Nominees" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 16, 2011. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Gomez, Patrick (May 26, 2020). "A Bug's Life is the technological marvel Pixar left behind". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Grebey, James (November 24, 2018). "Why A Bug's Life is an underrated Pixar classic". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on April 1, 2019. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ^ a b c Brew, Simon (December 5, 2010). "Celebrating the Pixar end-credits bloopers". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on July 12, 2021. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ^ a b Travis, Ben (February 3, 2021). "Every Pixar Movie Ranked – From Toy Story To Soul". Empire. Archived from the original on March 1, 2020. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ^ a b c Shutt, Mike (June 17, 2015). "Ranking All of Pixar's Films: From 'Toy Story' to 'Inside Out'". Comingsoon.net. Archived from the original on June 17, 2015. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ^ a b c Frank, Allegra; Abad-Santos, Alex; VanDerWerff, Emily; Romano, Aja; Wilkinson, Alissa (December 29, 2020). "All 23 Pixar movies, definitively ranked". Vox. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ^ Guerrasio, Jason (June 18, 2021). "RANKED: Every Pixar movie from worst to best — including 'Luca'". Business Insider. Archived from the original on July 12, 2021. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ^ a b Chitwood, Adam (June 18, 2021). "Every Pixar Movie Ranked from Worst to Best". Collider. Archived from the original on June 17, 2015. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ^ a b c Grierson, Tim; Leitch, Will (June 18, 2021). "All 24 Pixar Movies, Ranked". Vulture. Archived from the original on June 17, 2015. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Every Pixar movie, ranked". Polygon. January 19, 2021. Archived from the original on January 19, 2021. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ^ a b Iverson, Jon (February 14, 1999). "A Bug's Life Becomes First All-Digital DVD Release". Sound And Vision. Archived from the original on January 8, 2018. Retrieved January 6, 2018.

- ^ Andrews, Sam (March 16, 2000). "Sales of DVDs Soaring in the U.K." Billboard. Archived from the original on July 24, 2020. Retrieved January 6, 2018.

- ^ "A Bug's Life (Disney Gold Classic Collection) by Disney/Pixar". Amazon.com. Archived from the original on July 12, 2021. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- ^ "A Bug's Life (1998): 2003 Collector's Edition - DVD Movie Guide".

- ^ "2 'classics' on DVD; 'Bug's Life' is reissued". DeseretNews.com. Archived from the original on January 8, 2018. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ^ McCutcheon, David (March 17, 2009). "A Bug's Blu Life". IGN. Archived from the original on April 22, 2021. Retrieved April 22, 2021.

- ^ Heller, Emily (March 3, 2020). "A bunch of Pixar movies, including Up and A Bug's Life, come to 4K Blu-ray". Polygon. Archived from the original on March 4, 2020. Retrieved April 22, 2021.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (November 25, 1998). "A Bug's Life (1998)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 12, 2021. Retrieved May 6, 2012.

- ^ "A Bug's Life (Nintendo 64) reviews at". GameRankings. Archived from the original on April 11, 2013. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- ^ "A Bug's Life for Nintendo 64". GameRankings. April 30, 1999. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved November 29, 2013.

- ^ "Disney/Pixar A Bug's Life for PlayStation". GameRankings. October 31, 1998. Archived from the original on November 2, 2013. Retrieved November 29, 2013.

- ^ "Disney/Pixar A Bug's Life for Game Boy Color". GameRankings. Archived from the original on November 2, 2013. Retrieved November 29, 2013.

- ^ "Disney/Pixar A Bug's Life Review". GameSpot. Archived from the original on March 10, 2014. Retrieved November 29, 2013.

- ^ "A Bug's Life – IGN". Uk.ign.com. Archived from the original on March 2, 2016. Retrieved November 29, 2013.

- ^ "A Bug's Life – IGN". Uk.ign.com. Archived from the original on March 2, 2016. Retrieved November 29, 2013.

- ^ "It's Tough to be a Bug! | Walt Disney World Resort". Disney. Archived from the original on January 14, 2014. Retrieved January 13, 2014.

Further reading[]

- Price, David (2008). The Pixar Touch. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-307-26575-3.

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: A Bug's Life |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to A Bug's Life. |

- Official website

- Official website at Pixar

- A Bug's Life at IMDb

- A Bug's Life at the TCM Movie Database

- A Bug's Life at The Big Cartoon DataBase

- A Bug's Life at AllMovie

- 1998 films

- English-language films

- A Bug's Life

- 1998 animated films

- 1990s American animated films

- 1990s computer-animated films

- 1990s fantasy films

- American children's animated adventure films

- American children's animated comedy films

- American children's animated fantasy films

- American films

- Animated films about insects

- Best Animated Feature Broadcast Film Critics Association Award winners

- 1990s English-language films

- Fictional ants

- Fictional grasshoppers

- Films scored by Randy Newman

- Films directed by John Lasseter

- Films produced by Darla K. Anderson

- Pixar animated films

- Films with screenplays by John Lasseter

- Films with screenplays by Joe Ranft

- Films with screenplays by Andrew Stanton

- Walt Disney Pictures films

- Animated films set on islands

- Films based on Aesop's Fables