First Schober government

| First Schober government | |

|---|---|

Government of Austria | |

| |

| Date formed | June 21, 1921 |

| Date dissolved | January 26, 1922 |

| People and organisations | |

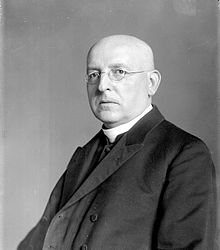

| Head of government | Johannes Schober |

| Deputy head of government | Walter Breisky |

| No. of ministers | 9 |

| Member parties | |

| History | |

| Election(s) | 1920 |

| Predecessor | |

| Successor | Breisky |

In Austrian politics, the first Schober government (German: Regierung Schober I) was a short-lived coalition government led by Johannes Schober, in office from June 21, 1921 to January 26, 1922. Although the coalition, consisting of the Christian Social Party and the Greater German People's Party, was unambiguously right of center, the government itself was supposed to be nonpartisan – a so-called "cabinet of civil servants" ("Beamtenkabinett") loyal to the country rather than to any particular faction. Eight of its eleven members, including the chancellor himself, were political independents and career administrators in the employ of the Republic. The government's main opponent was the Social Democratic Party.

The main challenges facing the first Schober government were Austria's lack of money, rampant inflation, and dependence on imports the country became increasingly unable to afford. The government was in desperate need of credit, but loans would not be forthcoming until Austria assuaged fears among the Allies of World War I that it might attempt to defy the Treaty of Saint-Germain. The Treaty forbade Austria to pursue accession into Weimar Germany, an idea that was popular in Austria at the time and that was in fact one of the People's Party defining platform planks. When Schober managed to open lines of credit through confirming Austria's commitment to independence in the Treaty of Lana, the People's Party forced his resignation.

Background[]

Economy[]

In the final decades of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the region that would later become the Republic of Austria had been dependent on Bohemian industry and on Bohemian and Hungarian agriculture for its standard of living. The Austria of 1921 was structurally weak and forced to import large amounts of food and coal from Czechoslovakia. The poor tax base and brutal trade imbalance prompted the Austrian government to print too much money. By 1921, the country had exhausted its reserves and inflation was galloping. Austria relied on foreign loans to keep buying Czechoslovak food and coal and to generally just keep running; it would require even more foreign loans, drastically larger ones, to reform its currency and to actually restructure. These loans would not be forthcoming, however, as long as the Allies of World War I could not be thoroughly certain that Austria would obey the provisions of the Treaty of Saint-Germain. There were still fears among the Allies that Austria might try to join the German Reich in defiance of the treaty; these fears had to be laid to rest.[1]

The Allies paid close attention to Austria's relationship with Czechoslovakia. Prague too was worried about a possible Austrian attempt to join Germany; Prague was also worried about a possible Austrian attempt to restore the Habsburgs to power. In March 1921, Charles I of Austria unsuccessfully attempted to reclaim the Hungarian throne. Although Hungary swiftly and roundly rebuffed the would-be king, the incident put additional strain on Austro-Czechoslovak relations. A resolution of the tensions would go a long way towards reassuring Austria's potential creditors.[2]

Political climate[]

The fourteen parties in Austria's Constituent Assembly had radically different visions regarding the constitutional, territorial, and economic future of their demoralized, impoverished rump state. The Social Democratic Party controlled a plurality but not a majority of the seats. It eventually formed a grand coalition with the Christian Social Party, the largest party on the right and the second-largest party overall. The grand coalition was a pragmatic choice but not an ideologically undemanding one. The government found itself blocked at every turn by party leaders' unwillingness to compromise. No other alliance would have commanded the support of a stable parliamentary majority. Austrians began to warm to the idea of a "cabinet of civil servants" ("Beamtenkabinett"), a government of senior career bureaucrats who would be loyal to the country and not to any particular ideological camp. The Habsburg Empire had consciously cultivated an ethos of partisan neutrality in its civil servants. A pool of highly educated middle-aged administrators who counted sober professionalism as an important aspect of their self-image stood ready to be tapped.[3]

The grand coalition had fallen apart by June 1920, but the right-of-center alliance succeeding it was not much more efficient. The idea of a cabinet of independents was still popular, and Johannes Schober was an obvious choice for the person to lead it. The Vienna Chief of Police enjoyed wide name recognition and was respected across party divides for his competence and effectiveness. He also enjoyed a reputation for personal integrity, an important point in a country sick of corruption and nepotism.[4] He was known to be close to the pan-German cause but still considered nonpartisan.[5][6]

Another obvious candidate for chancellor was Ignaz Seipel, the leader of the Christian Socials, who had displaced the Social Democrats as the plurality party in the elections of 1920. Seipel, however, was reluctant to assume the chancellorship because of the difficult decisions and general hardship he knew still lay ahead; he wanted someone else to do the dirty work.[7][8]

The Republic of German-Austria had been proclaimed with the understanding that it would eventually join the German Reich, a vision shared by a clear majority of its population at the time. The treaties of Versailles and Saint-Germain prohibited a union of the two countries, but unification remained popular.[9][10][11] In early 1921, several provincial governments hatched plans to break away from Austria and join Germany on their own; preparations for local referendums were made. Chancellor Michael Mayr ordered the would-be defectors to cease and desist but was ignored. Having lost its authority, the resigned on June 1, 1921. Schober looked like the man of the hour to politicians from all over the political spectrum.[12][13]

Composition[]

The government consisted of the chancellor, the vice chancellor, and nine ministers. There were a number of idiosyncrasies. Chancellor Schober doubled as the minister of foreign affairs, but technically only in an acting capacity (mit der Leitung betraut) and not as a minister proper. The Ministry of Nutrition of the Population too was led by an acting minister. The Ministry of the Interior and the Ministry of Education, historically independent but merged since the second Renner government, were not yet separated again, but in addition to the actual minister there was a state secretary (Staatssekretär) in charge of education affairs (betraut mit der Leitung der Angelegenheiten des Unterrichts und Kultus).[14]

The Schober government, like its predecessor, depended on a coalition of Christian Social Party and Greater German People's Party for its support in the National Council. It therefore contained two symbolic Christian Social representatives and one symbolic People's Party delegate. The remaining eight of its eleven members were political independents.[13]

| Department | Office | Officeholder | Party |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chancellery | Chancellor | Johannes Schober | none |

| Vice chancellor | Walter Breisky | CS | |

| Ministry of Education and the Interior | Minister | GDVP | |

| In charge of education | Walter Breisky | CS | |

| Ministry of Justice | Minister | none | |

| Ministry of Finance | Minister | none | |

| Minister | none | ||

| Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Construction | Minister | none | |

| Ministry of Social Affairs | Minister | none | |

| Ministry of Foreign Affairs | Acting minister | Johannes Schober | none |

| Ministry of the Army | Minister | Carl Vaugoin | CS |

| Ministry of Nutrition of the Population | Acting minister | none | |

| Ministry of Transport | Minister | none |

Three ministers were replaced on October 7, 1921:[14]

| Department | Office | Officeholder | Party |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ministry of Finance | Minister | Alfred Gürtler | none |

| Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Construction | Minister | none | |

| Ministry of the Army | Minister | none |

The People's Party representative in the cabinet resigned on January 16, 1921; Schober took over from him:[14]

| Department | Office | Officeholder | Party |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ministry of Education and the Interior | Acting minister | Johannes Schober | none |

| In charge of education | Walter Breisky | CS |

Activity[]

The emergency the Schober government had to deal with most urgently were the referendums on unification with Germany that a number of provinces were preparing. Schober convinced the provinces to abandon their plans. Schober succeeded where Mayr had failed partly because he was known to be pan-German himself, partly because he took, in addition to the chancellorship, personal control of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Schober's installation as both the chancellor and the foreign minister created the impression – the false impression, as it later turned out – impression that the pan-German cause was in good hands and that unsolicited unilateral action on the part of the regional governments would not be needed.[15]

The provinces appeased, Schober next tried to improve Austria's poor relations with Czechoslovakia. The Czechoslovak foreign minister, Edvard Beneš, helpfully took the first step. Czechoslovakia had just created the Little Entente, an alliance of Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, and Romania that was meant to restrain Hungarian claims against its neighbors and to thwart Italy's attempts to assert dominance over the region. An Austrian accession to the Little Entente or, failing that, an Austrian declaration of support for the Little Entente, would have been highly useful to Czechoslovakia. Beneš ventured to impress the benefits of an alliance with Czechoslovkia on the Austrian ambassador. In his reply to Beneš, Schober insisted that Austria would not be able to join the Little Entente – due to the policy of neutrality that had been imposed on his rump state by the Treaty of Saint-Germain – but that Schober would be more than happy to meet with Beneš in order to discuss what could be done instead. Schober also expressed his hope that Beneš would find it in his heart to help open up lines of credit for Austria, by putting in a good word for the country "in Paris and London".[16]

Beneš accepted the invitation. On August 10, 1921, Beneš and Tomáš Masaryk, the Czechoslovak president, traveled to Hallstatt and negotiated a compact of mutual understanding and support with their Austrian counterparts, Schober and Michael Hainisch. In the Political Agreement between the Republic of Austria and the Czechoslovak Republic (Politisches Abkommen zwischen der Republik Österreich und der Tschechoslowakischen Republik), the two countries promised each other to honor the Treaty of Saint-Germain, to respect each other's borders, to support each other diplomatically, and to remain neutral if either of them should be attacked by a third party. They further promised each other not to tolerate any activity on their respective soil that aimed to undermine the security of the respectively other, and to support each other against any attempt to restore the Habsburg regime.[17]

The agreement was signed on December 16 during a return visit of the Austrians to Lány Castle, the summer seat of the Czechoslovak president. It became known as the Treaty of Lana (Vertrag von Lana) after the German name of the castle, Schloss Lana.[18][19] On the occasion of the exchange of signatures, Czechoslovakia promised to grant Austria an immediate loan of CZK 500 million and to support Austria's entreaties for more money in France and the United Kingdom.[20]

Resignation[]

From the point of view of Schober, the Treaty of Lana was a resounding success. Austria had conceded nothing it had not conceded already in the Treaty of Saint-Germain. The treaty was a symbolic gesture, renewing old promises without making any new ones, but all the same a gesture that Czechoslovakia would handsomely reward. From the point of view of the People's Party, the treaty was tantamount to treason. The two defining platform planks of the People's Party were Antisemitism on the one hand and pan-Germanism on the other hand. The party had been hoping that Austria would, sooner or later, defy the Treaty of Saint-Germain and would seek accession to the German Reich. The party had also been hoping that the unification of all Germans would extend to the Sudeten Germans, the German-speaking former Habsburg subjects living in what used to be Bohemia. Schober, whom the party had considered a reliable ally, was renouncing both these goals.[21]

In the final days of December 1921, the People's Party staged protest rallies against the treaty all over the country. Protests were also organized by other pan-German groups, including the nascent Nazi Party. Adolf Hitler traveled from Munich to Vienna to rail against the treaty in front of some six hundred sympathizers, a notable early appearance.[22][23]

On January 16, 1922, the People's Party also withdrew its representative in Schober's cabinet, . As long as Schober himself remained office, however, the People's Party was still bound by the original coalition agreement. The agreement required the party to vote in support of government bills in the National Council, and one of the government bills on the table in January 1922 was the ratification of the Treaty of Lana. Anxious to ensure the survival of the coalition, Schober defused the issue through resigning. On January 26, 1922, Schober stepped down. His vice chancellor Walter Breisky was sworn in as his successor, and the Treaty of Lana was ratified with the votes of Christian Socials and Social Democrats. The Breisky government was scrapped after a single day in office, and Schober returned to the chancellorship as the head of the second Schober government.[24]

Citations[]

- ^ Portisch 1989, pp. 297–298.

- ^ Portisch 1989, pp. 284, 298–299.

- ^ Wandruszka 1983, pp. 62, 65, 70.

- ^ Wandruszka 1983, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Orde 1980, p. 41.

- ^ Portisch 1989, p. 293.

- ^ Klemperer 1983, p. 102.

- ^ Weyr 2005, p. 47.

- ^ Orde 1980, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Pelinka 1998, p. 11.

- ^ Portisch 1989, pp. 310–311.

- ^ Portisch 1989, pp. 286–293.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wandruszka 1983, p. 66.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Schober I.

- ^ Portisch 1989, pp. 293–294.

- ^ Portisch 1989, pp. 298–300.

- ^ BGBl. 173/1922.

- ^ Arbeiter-Zeitung, December 17, 1921.

- ^ Portisch 1989, pp. 300–301.

- ^ Portisch 1989, p. 302.

- ^ Portisch 1989, pp. 302–304.

- ^ Auer 1966.

- ^ Portisch 1989, pp. 303–304.

- ^ Portisch 1989, pp. 304–305.

References[]

- Auer, Johann (April 1966). "Zwei Aufenthalte Hitlers in Wien" (PDF). Vierteljahreshefte für Zeitgeschichte. Munich and Berlin: Institut für Zeitgeschichte. 14 (2): 207–208. Retrieved September 7, 2018.

- "Die Zusammenkunft der Präsidenten". Arbeiter-Zeitung. December 17, 1921. p. 4. Retrieved September 7, 2018.

- Klemperer, Klemens (1983). "Ignaz Seipel". In Weissensteiner, Friedrich; Weinzierl, Erika (eds.). Die österreichischen Bundeskanzler. Vienna: Österreichischer Bundesverlag. ISBN 978-3-215-04669-8.

- Orde, Anne (1980). "The Origins of the German-Austrian Customs Union Affair of 1931". Central European History. Cambridge University Press. 13 (1): 34–59. doi:10.1017/S0008938900008992. JSTOR 4545885.

- Pelinka, Peter (1998). Out of the Shadow of the Past. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-2918-5.

- "Politisches Abkommen zwischen der Republik Österreich und der Tschecho-slowakischen Republik, BGBl. 173/1922". March 30, 1922. Retrieved September 7, 2018.

- Portisch, Hugo (1989). Österreich I: Band 1: Die unterschätzte Republik. Vienna: Kremayr & Scheriau. ISBN 978-3-453-07945-8.

- "Schober I". Austrian Parliament. Retrieved August 31, 2018.

- Wandruszka, Adam (1983). "Johannes Schober". In Weissensteiner, Friedrich; Weinzierl, Erika (eds.). Die österreichischen Bundeskanzler. Vienna: Österreichischer Bundesverlag. ISBN 978-3-215-04669-8.

- Weyr, Thomas (2005). The Setting of the Pearl. Vienna under Hitler. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514679-0.

- 1921 establishments in Austria

- 1922 disestablishments in Austria

- Austrian governments

- 1920s in Austria