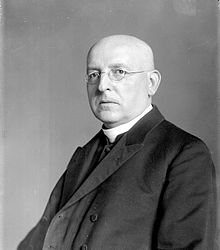

Johannes Schober

Johannes Schober | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chancellor of Austria | |

| In office 26 September 1929 – 30 September 1930 | |

| President | Wilhelm Miklas |

| Deputy | Carl Vaugoin |

| Preceded by | Ernst Streeruwitz |

| Succeeded by | Carl Vaugoin |

| In office 27 January 1922 – 31 May 1922 | |

| President | Michael Hainisch |

| Deputy | Walter Breisky |

| Preceded by | Walter Breisky |

| Succeeded by | Ignaz Seipel |

| In office 21 June 1921 – 26 January 1922 | |

| President | Michael Hainisch |

| Deputy | Walter Breisky |

| Preceded by | Michael Mayr |

| Succeeded by | Walter Breisky |

| Personal details | |

| Born | November 14, 1874 Perg, Lower Austria |

| Died | August 19, 1932 (aged 57) Baden bei Wien, Austria |

| Political party | Independent |

| Mother | Clara Schober |

| Father | Franz Lorenz Schober |

| Alma mater | University of Vienna |

| Profession | Police executive |

Johannes "Johann" Schober (born November 14, 1874 in Perg; died August 19, 1932 in Baden bei Wien) was an Austrian jurist, law enforcement official, and politician. Schober was appointed Vienna Chief of Police in 1918 and became the founding president of Interpol in 1923, holding both positions until his death. He served as the chancellor of Austria from June 1921 to May 1922 and again from September 1929 to September 1930. He also served ten stints as an acting minister, variously leading the ministries of education, finance, commerce, foreign affairs, justice, and the interior, sometimes just for a few days or weeks at a time. Although Schober was elected to the National Council as the leader of a loose coalition of Greater German People's Party and Landbund near the end of his career, he never formally joined any political party. Schober remained the only chancellor in Austrian history with no official ideological affiliation until 2019, when Brigitte Bierlein was appointed, becoming the first woman to take office.

Early life[]

Johannes Schober was born on November 14, 1874 in Perg, Upper Austria.[1]

Schober was the tenth child of Franz Schober, a senior civil servant and veteran of Radetzky's Italian campaigns, and Klara Schober, née Lehmann, a smallholder's daughter.[2] On his father's side, the family came from money and prestige; Schober's paternal grandfather had been a physician. As was common among Catholic Austrians who were upper middle class but not quite upper crust, Schober's parents combined an ethos of obedience to Church and State with a broad pan-German streak and a strong attachment to their rural homeland with an appreciation for the humanities and the arts. The education they imparted on young Johannes appears to have emphasized hard work, piety, and patriotism.[3]

The boy showed considerable academic aptitude during his years in the local elementary school and was thus groomed for university education from an early age. He attended the gymnasium in Linz and the Vincentinum, a Catholic boys' boarding school. Even though he had to work as a private tutor to pay his way, his grades were excellent. In 1894, having completed his secondary education, Schober enrolled at the University of Vienna to read law. A great lover of music, he joined the Academic Choral Society (German: Akademischer Gesangverein), a type of Burschenschaft.[4][5]

Career[]

Service in the Empire[]

In 1898, Schober left the university and joined the Rudolfsheim police inspectorate as an apprentice clerk (Konzeptspraktikant). He had completed his studies but had either not taken or not passed the complete set of graduation exams. He left, accordingly, not with a doctorate but an absolutorium. Being nothing but a glorified certificate of attendance, the absolutorium did not qualify its holder to receive the post-graduate education necessary to become a lawyer in private practice, a prosecutor, or a judge. Even so, it technically made its holder a person of academic rank. As such, it was good enough to permit admission into higher civil service. In particular, it qualified Schober to receive post-graduate training for the position of lawyer in police service (Polizeijurist). By 1900, Schober had completed his training with distinction and was assigned to the prestigious Innere Stadt inspectorate. Schober had been induced to join the police by one of his favorite operas, the Evangelimann, a play based on the 1892 autobiography of a Viennese detective inspector.[6]

Because Schober was fluent not just in German and French but also in English, he was put in charge of protecting Edward VII during Edward's summer holidays in Marienbad. His proximity to the British monarch for six consecutive summers appears to have been the basis for the friendly relations to the English-speaking world that Schober was noted for later in life. The assignment also seems to have been a boost for his career. He was promoted to a position in the Ministry of the Interior proper, where he was involved in watching over the Emperor and the Imperial Family – protecting them, but also keeping them under surveillance. Effective March 1, 1913, at the relatively young age of 38, Schober was made one of the heads of the Office of State Security (Staatspolizei). When World War I broke out a little over a year later, Schober thus found himself one of the chiefs of Austrian counter-intelligence operations. He became noted for his lenient disposition. When , the Vienna Chief of Police, was made Minister of the Interior in June 1918, Schober was appointed his successor. Schober also received the honorary title of Hofrat on the occasion.[7][8]

Chief of Police[]

During the chaos days of the collapse of the Empire in late 1918, Schober's tact and resourcefulness played a crucial role in maintaining peace and public order in Vienna.[9] Following the proclamation of the Republic of German-Austria on November 12, Schober placed his forces at the disposal of the provisional government but also secured the safety of the Imperial Family, whose departure from Vienna he supervised.[10] Leaders of multiple major parties – especially Social Democrats, and Karl Renner in particular – declared themselves grateful. On November 30, the provisional government confirmed Schober in his position as the Vienna Chief of Police. On December 3, he was put in charge of public safety (öffentliche Sicherheit) in the rest of the country as well.[11]

Austria's Communists, even though they envisioned the establishment of a soviet republic instead of the parliamentary system that Austria was headed for, had been largely peaceful during the critical months between October 1918 and February 1919. The Social Democrats had pursued, with apparent success, a strategy of absorbing and assimilating them; the provisional Austrian army had absorbed and assimilated their party militia.[12] No Communist Party had run in the February 1919 Constituent Assembly elections.[13] In March, however, Béla Kun's establishment of the Hungarian Soviet Republic encouraged parts of the Communist leadership to try to seize power by force. Protests with thousands of participants were orchestrated, some of them ending in clashes of protesters with police. A confrontation on April 17 killed 5 police and a female civilian. A further 36 police and 30 civilians were injured, many of them severely. The protesters set fire to the parliament building.[14]

The harsh positions taken by the victorious Allies in the Paris Peace Conference, especially the reparations payments they were preparing to impose, heightened the tensions.[15][16] The Communists began preparing a mass protest for June 15, urging their supporters to carry arms and hoping to turn the march into an insurrection. A conference of party leaders on June 14 was meant to finalize marching orders. Informed of these plans, Schober petitioned the government to disallow the protest. When the government declined, Schober had security police raid the conference and arrest all 122 participants. The next day, a demonstration demanding the release of the prisoners precipitated a bloody street fight that left 12 protesters dead and 80 seriously injured.[17]

Schober's crackdown earned him the trust of the political right.[18][19]

He was now considered "a tough law-and-order man."[20]

Abortive bid for the chancellorship[]

The fourteen parties in Austria's Constituent Assembly had radically different visions regarding the constitutional, territorial, and economic future of their demoralized, impoverished rump state. The government, a grand coalition of Social Democrats and Christian Social Party, found itself blocked at every turn by party leaders' unwillingness to compromise. No other alliance would have commanded the support of a stable parliamentary majority. Austrians began to warm to the idea of a "cabinet of civil servants" ("Beamtenkabinett"), a government of senior career bureaucrats who would be loyal to the State and not to any particular ideological camp. The Habsburg Empire had consciously cultivated an ethos of partisan neutrality in its civil servants. A pool of highly educated middle-aged administrators who counted sober professionalism as an important aspect of their self-image stood ready to be tapped.[21]

When the grand coalition fell apart in June 1920, Schober looked like the man of the hour to many. He was known to be close to the pan-German cause but still considered nonpartisan.[22] Ignaz Seipel, chairman of the Christian Social Party, was reluctant to assume the chancellorship because of the difficult decisions and general hardship he knew still lay ahead; he wanted someone else to do the dirty work.[20][23] Schober was respected across party divides for his competence and effectiveness. He also enjoyed a reputation for personal integrity, an important point in a country sick of corruption and nepotism. All but unanimously, the new National Council invited Schober to draw up a list of ministers. When Schober chose as his Finance Minister, a post that Redlich had already held for a short while during the final days of the collapsing Empire, the Greater German People's Party vetoed Redlich on the grounds that Redlich was Jewish. Schober bowed out. Michael Mayr became chancellor in his stead.[24]

First government[]

Mayr's term as a chancellor lasted less than a year. The Republic of German-Austria had been proclaimed with the understanding that it would eventually join the German Reich, a vision shared by a clear majority of its population at the time. The treaties of Versailles and Saint-Germain prohibited a union of the two countries, but unification remained popular.[25][26][27] Several provincial governments hatched plans to break away from Austria and join Germany on their own; preparations for local referendums were made. Mayr ordered the would-be defectors to cease and desist but was ignored. Having lost its authority, the resigned on June 1, 1921. Schober was asked to step up, agreed, and became Chancellor of Austria on June 21.[28][29]

The cabinet was supported by a coalition of Christian Social Party and Greater German People's Party, but eight of its eleven members were independents. The Christian Socials Walter Breisky and Carl Vaugoin served as the vice chancellor and the minister of the army, respectively; the People's Party's served as the minister of education and the interior. The remaining seven ministers were, like Schober himself, veteran civil servants with no overt party affiliation. In addition to holding the chair, Schober led the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, although only in an acting capacity (mit der Leitung betraut) and not as an actual minister.[30]

The main problems facing Schober's cabinet were Austria's galloping inflation and the country's unresolved relationship with Czechoslovakia. Austria depended on its neighbor to the north for food and coal – food and coal it was increasingly unable to afford. Austria needed credit, not just for essential consumables but also in order to restructure. No loans would be forthcoming, however, as long as the Allies could not be thoroughly certain that Austria would obey the provisions of the Treaty of Saint-Germain.[31] Prague was still worried about a possible Austrian attempt to join Germany and also about a possible Austrian attempt to restore the Habsburgs to power; amicable relations with Czechoslovakia would go a long way towards reassuring Austria's potential creditors.[32]

On December 16, Chancellor Schober and President Michael Hainisch signed the Treaty of Lana, promising to honor the Treaty of Saint-Germain, to refrain from interfering in Czechoslovak internal affairs, and to remain neutral in the event on an attack on Czechoslovakia by a third party. Their counterparts, Tomáš Masaryk and Edvard Beneš, made equivalent promises in return. They also promised to put in a good word for Austria in London and Paris and, in fact, committed to a generous loan themselves. From the point of view of Schober, the treaty was a great success. Austria had given away nothing that had not long been lost already, and the symbolic gesture had been handsomely rewarded. From the point of view of the People's Party, the treaty was tantamount to treason. Austria had further reduced its chances of ever joining Germany and had sold out the Sudeten Germans to boot.[33]

On January 16, the People's Party representative in Schober's cabinet, Waber, resigned his post; Schober and Breisky took over as acting ministers of the interior and of education, respectively.[30] Unable to govern without the support of the People's Party, Schober ultimately stepped down himself on January 26. Breisky was appointed his successor.[29][34]

Second government[]

Schober's resignation ended the coalition and therefore relieved the People's Party of its contractual obligation to side with the cabinet in the National Council, i.e. to support the ratification of the Treaty of Lana. The treaty was ratified with the votes of Christian Socials and Social Democrats. Having been able to vote in opposition, the People's Party was partially appeased and was ready to resume support for the Schober government, who in any case was still the only plausible contender. Schober resumed the chancellorship on January 27. Breisky had been in office for barely twenty-four hours.[29][35] Breisky went back to being vice chancellor. Schober returned as acting minister of the interior, although not as acting minister of foreign affairs.[36]

Reluctant support in the National Council nonwithstanding, the nationalists never forgave Schober for the Treaty of Lana. While Schober continued to fight Austria's crippling financial problems and otherwise focused on foreign policy, Seipel, still the chairman of the Christian Social Party, decided that the time had come for him to take over. In April, Schober left the country to participate in the crucial Genoa Conference. His opponents used his absence to orchestrate his replacement. In May, already on his way home, Schober learned that the Christian Socials had withdrawn their support his cabinet.[29][37] Schober resigned on May 24; he agreed to stay on in a caretaker capacity until the could be sworn in on May 31.[36]

Return to law enforcement[]

Ousted as chancellor, Schober resumed his duties as the Vienna Chief of Police and the man in charge of Austrian public safety. He undertook to modernize the force, to expand its capacities, and to intensify international cooperation. In 1923, Schober convened the Second International Police Congress and took the initiative in creating Interpol.[38] He personally assumed the role of Interpol's founding president.[39] Schober otherwise focused on centralizing the Austrian police corps' command structure and on strengthening traffic police, criminal police, the intelligence network, and the force's internal welfare program. He also worked to reduce to influence of Social Democrats on the force.[40]

July Revolt[]

On January 30, 1927, members of the Frontkämpfer militia opened fire on an unarmed and unsuspecting crowd of Social Democrats in an ambush attack in the small town of Schattendorf, killing two and wounding five others.[41] The Frontkämpfer were a right-wing vigilante group of war veterans, originally founded by disgruntled officers but also recruiting among the enlisted. Their stated aims were "uniting all Aryan front-line fighters" ("Vereinigung aller arischen Frontkämpfer"), "nurturing the love for the homeland" ("Pflege der Liebe zur Heimat"), fighting leftists, and suppressing Jews. Their membership numbered in the thousands; a rally in 1920 appears to have attracted some sixty thousand sympathizers. The group's main activity was assaulting Social Democrats and Communists and disrupting their meetings. In 1927, the group was in the process of being assimilated into the Nazi Party, a process that would be completed by 1929.[42]

The killings caused considerable outrage. The shooting had been a surprise attack from a concealed position. One of the slain was a disabled veteran and father. The other dead body was that of a young child, the only child of an impoverished family. Tensions between the parties rose so high as to completely paralyze the National Council. All useful work having ground to a halt, the legislature voted to dissolve itself and called for early elections.[43]

The Frontkämpfer had killed Social Democrats before, but the resulting trials had usually ended in acquittals or conspicuously lenient sentences. The Social Democrats now announced that they had had enough; their opponents in turn accused them of trying to exert undue pressure on the judiciary. On July 14, the two Frontkämpfer charged with the shooting where acquitted.[44] Workers and other Social Democrats in Vienna reacted with spontaneous strikes and protests. Party leadership was hesitant to stoke the flames but lost control. The police appeared disorganized and overwhelmed. Skirmishes ensued. Unfounded rumors accused the police of murdering protesters, the protesters of lynching police. Around noon on July 15, an angry mob cordoned off the Palace of Justice and set fire to the building, then prevented the fire brigade from moving in. Fearing for the lives of those trapped inside the Palace, police decided to disperse the mob by shooting their rifles – mainly into the air, but also into the crowd.[45] At the end of the day, 4 police and 85 protesters were dead; some 600 police had been injured. The number of injured civilians was difficult to ascertain because many avoided seeking medical assistance for fear of prosecution. Hospitals reported that 328 had been admitted for inpatient treatment; the total number of civilians hurt was 548 according to the authorities and 1057 according to the Arbeiter-Zeitung.[46]

Although Schober had been mostly uninvolved in the events of July 15, the Social Democrats laid the blame for the loss of life squarely at his door. The Arbeiter-Zeitung called him a "bloodhound" ("Bluthund") and a "murderer of workers" ("Arbeitermörder"). Schober became a deeply controversial figure for the rest of his life and for decades beyond.[47] Noted public intellectuals such as Karl Kraus, an eminent writer and erstwhile admirer of Schober's, joined the attacks. Kraus accused Schober of "fecklessness, deceitfulness, and abuse of power" and called for Schober to resign.[48] He launched a poster campaign and railed against Schober in a 1928 stage play, The Insurmountables (Die Unüberwindlichen).[49][50] In what has been called a "crusade" by commentators, Kraus would make Schober his prime target until the day Schober died.[51]

Schober, who sincerely believed that he had always treated the Social Democrats with fairness and whose skin was thinner than his reputation suggested, experienced the attacks as vicious and appears to have been genuinely hurt. He was elated when Karl Seitz, a leading Social Democrat and the Mayor of Vienna, extended a personal apology in 1929.[52]

Third government[]

In spite of the successful integration of Austria into the international community that Schober – and later Seipel – achieved, the country's economic situation continued to deteriorate.[53][54] The currency collapsed into hyperinflation. Inflation was brought under control through a currency reform, but the foreign creditors funding this reform demanded a course of strict austerity that made most Austrians even poorer. Unemployment was high, unemployment benefits and pensions were inadequate.[55][56] In fact, even Austrians in stable formal employment had trouble meeting basic needs.[57]

Partisan strife also continued to worsen. Inspired by the apparent successes of Fascist movements abroad, frustrated by the Austrian democracy's inability to put the nation back on track, and distressed by the July Revolt, an increasing number of Austrians on the political right believed that the country's elites in general, and its parliamentary system in particular, needed to be swept away.[58] A strongman was called for to end the infighting, shut down the Social Democrats, and put the Jews in their place. A system of thought developed that combined Fascism, Catholic clericalism, and the Antisemitism traditionally endemic in large parts of the Austrian political right.[59] The resulting Austrofascist Heimwehr movement was loosely affiliated with the Christian Social Party; it had the support of much of the party's core constituencies and of many, although not all, of the party's leaders. By 1929, the Heimwehr had become a serious danger to Austrian democracy. It demanded that Austria's parliamentary democracy be replaced with a presidential system and threatened insurrection should the government refuse.[60][61][62]

The threats were credible.[63]

The Streeruwitz government, a coalition of Christian Social Party, People's Party, and the agrarian Landbund, engaged the Heimwehr in negotiations regarding constitutional reform.[60][64][65] Heimwehr, government, and Social Democrats were close to a compromise when, in late September, Heimwehr and Christian Social Party brought down Streeruwitz anyway.[66][67] Seipel was still leading the Christian Social Party but once again had no desire to step up and assume responsibility himself. As he had done in 1921, Seipel chose to install Schober instead.[68]

The third Schober government was sworn in on September 26. Like Schober's previous two cabinets, it consisted mainly of political independents. Schober's picks included Michael Hainisch and Theodor Innitzer. A former president of Austria and a noted professor of theology, respectively, Hainisch and Innitzer enjoyed wide name recognition and broad respect with the general public.[69] Schober himself became acting minister again, this time leading the ministries of education and of finance.[70]

Any hope of economic recovery was instantly squashed by the Wall Street Crash of 1929, striking a mere four weeks after Schober's inauguration. The Great Depression hit Austria even harder than most other countries. Austria still depended on regular foreign cash infusions, but credit quickly dried up as a result of the downturn.[71] The government was successful in other respects, however.[69] Most importantly, Schober neutralized the threat of Heimwehr revolt. On the one hand, he signalled willingness to meet Heimwehr demands for constitutional reform halfway, continuing negotiations where the Streeruwitz government had left off. On the other hand, he pointedly refused to include Heimwehr men in his cabinet and insisted that the new constitution be implemented legally, i.e. pursuant to the amendment rules laid down in the existing constitution. The new constitution would need the support of two thirds of the members of the National Council, meaning that it could not be passed without the assent of the Social Democrats. Schober invited Social Democratic representatives to join the talks and refused to be intimidated by the rallies the Heimwehr kept staging as a show of force.[72][73] Eventually, a compromise was reached; the Council passed a set of amendments to the Federal Constitutional Law on December 7, 1929. The compromise significantly strengthened the power and prestige of the office of the president. It also altered appointment procedures to the Constitutional Court in a way that the Heimwehr thought would guarantee right-of-center majorities for the foreseeable future.[74][75] The compromise was a disappointment for the Heimwehr and its foreign allies, and a victory for the Social Democrats, in all other respects.[76]

Schober was also successful on the foreign policy front. In particular, Schober convinced the Allies of World War I, on a conference in The Hague in January 1930, to forgive the reparations that Austria still owed. Observers noted that Schober achieved his diplomatic victories through a strategy of comporting himself as an affable simpleton. Short, pudgy, intellectually outmatched, eager to oblige, happy to be patronized, and head of a country that was no threat to anyone any more, Schober seems to have put his negotiating partners into a generous mood. According to one contemporary Austrian cartoon, Schober received so many friendly pats on the shoulder from foreign dignitaries that he took to traveling with a cushion strapped to his back.[77]

Dissatisfied by the new constitution and in financial straits due to a crisis in the Austrian banking sector that had toppled one of its main donors, the Heimwehr decided that the way forward was to increase the pressure again. A Heimwehr rally in Korneuburg on May 18 culminated in de facto declaration of war on the Republic, a firm promise of armed insurrection. One of the leaders of the radical element in the Heimwehr at the time was Waldemar Pabst, a German national. Schober had Pabst deported.[78]

The Heimwehr was now determined to get rid of Schober.[79] The Christian Socials agreed to help. The party was jealous of Schober's successes; the relationship was strained additionally by personal tensions between Schober and Seipel and between Schober and his Vice Chancellor, Carl Vaugoin.[80] Vaugoin, a friend of the Heimwehr to begin with, provoked a quarrel with Schober by demanding that be appointed director general of the Austrian Railways; Strafella was both a noted Heimwehr man and known to be corrupt. When Schober refused, Vaugoin ostentatiously resigned on September 25. Realizing that his cabinet was unable to carry on, Schober submitted his own resignation the same day.[81][82]

Schober Bloc[]

On the one hand, the 1929 constitutional reform meant that chancellor and cabinet would no longer be elected by the National Council but appointed by the president. On the other hand, the cabinet still depended on majority support in the National Council to be able to govern effectively. On the third hand, the reform also vested the president with the power to dissolve the National Council, forcing new elections.[74][75] President Wilhelm Miklas, a Christian Social himself, appointed a cabinet consisting exclusively of Christian Social politicians and Heimwehr chiefs. He installed Vaugoin as Schober's successor and Seipel as his minister of foreign affairs. Ernst Rüdiger Starhemberg, a Heimwehr leader, became Minister of the Interior. , another Heimwehr leader and brother in law of Hermann Göring, became minister of justice.[83] Lacking support from either of the Christian Socials' traditional coalition partners – the nationalist Greater German People's Party and the agrarian Landbund – the was stillborn. Miklas dismissed the legislature and called a snap election for November 9.[84]

The Heimwehr, made confident by its easy victory over Schober and intrigued by the successes of the Nazi Party in Germany, now decided to break with the Christian Socials and stand for election as a separate party, the Homeland Bloc (Heimatblock).[85] Instantly, fears of a possible Heimwehr putsch resurged; the country felt that civil war was in the air. People's Party and Landbund united against their common enemy and convinced Schober to serve as the leader of their alliance, which they proceeded to name the Schober Bloc (Schober-Block).[86][87]

The Austrian legislative elections of November 9, 1930 resolved, once again, nothing. Except for the fact that the Heimwehr won a meager eight seats, taking seven of them from the Christian Socials, the composition of the National Council remained virtually unchanged. Thanks to the Heimwehr splitting the Christian Social vote, the Social Democrats were the plurality party again. With no actual majority and no potential coalition partners, the victory was hollow, however.[88] The Vaugoin government, still without majority support, resigned on November 29. Otto Ender, the Christian Social governor of Vorarlberg, swiftly repaired the coalition of Christian Socials, People's Party, and Landbund and was sworn in as the new chancellor on December 4. The included both Schober, this time as the vice chancellor and acting minister of foreign affairs, and Vaugoin, who resumed his position as minister of the army.[89][90]

The main item on the Ender government's agenda was Austria's economic situation, still deteriorating and utterly desperate by now. In a country of 6.5 million, the number of unemployment working-age adults was approaching 600,000.[55] Only about half of them were receiving unemployment benefits. Heavy industry was shutting down; in industrial cities such as Steyr and Leoben, more than half the population had no remaining income whatsoever. Children went hungry and often literally barefoot.[91] When Julius Curtius, foreign minister of the German Reich, visited Vienna on March 3, 1931, Schober and Curtius negotiated a customs union between the two neighbors. The idea had already been floated in 1917 and then in 1927, and it still made eminent sense for both sides. Austria's manufacturing sector would gain better access to the German market. Germany would gain access to Southeast Europe and would economically encircle both Czechoslovakia and Poland; in the long term, Czechoslovakia and Poland might choose to realign themselves away from France, their preferred partner in 1931, and towards the great power they actually bordered.[92][93]

Both Schober and Curtius knew that the Allies would not permit the union. France in particular would be vehemently opposed; the French were worried that German economic recovery would lead to renewed German military dominance.[94] France, however, was known to be hatching its own plans for European economic unification, to be negotiated under the auspices of the League of Nations. Schober and Curtius hoped they would be able to convince Paris to permit their customs union in the context of these negotiations.[95] They resolved to keep their agreement secret for the time being.[96][97] When the agreement was leaked, France, as predicted, immediately vetoed it.[98][99] Germany and Austria considered implementing the customs union anyway, but the sudden implosion of the Creditanstalt in May laid these plans to rest.[98] The Creditanstalt was Austria's largest bank and controlled two thirds of its remaining industry. To prevent the total collapse of its economy, Austria now needed an immediate cash infusion in an amount that the struggling Reich was unable to muster. France agreed to help, on the condition that the customs union be abandoned and that Austria agree to have its finances audited by the League of Nations; Austria would also have to promise to implement whatever restructuring measures the League would subsequently recommend.[100]

Ender could not stomach these conditions. He resigned on June 20, handing the reins to Karl Buresch, who could.[101]

Schober stayed on, serving in the both as the vice chancellor and as the acting minister of foreign affairs.[102] The enmity of the French he had earned for himself, however, meant that his ability to function as a foreign minister was severely limited now.[103] When his continued presence in the cabinet endangered the issuance of a strategic foreign currency bond, the Buresch government resorted to a sham resignation to remove Schober from office.[40][104]

Death[]

Schober died on August 19, 1932. His death was not unexpected. Schober had been suffering from heart disease; his condition had noticeably worsened during his final months. It has been speculated that his end may have been hastened by disappointment and bitterness; Schober believed he had been treated shabbily by his political allies.[104]

Schober's death came a mere three weeks after the death of Ignaz Seipel, who had also been struggling with long illness.[105] The coincidence was widely noted. The two former enemies had reconciled during their final days, conveying best wishes to each other "from sickbed to sickbed."[104]

Honors[]

- 1930: Honorary doctorate of technical sciences of the Graz University of Technology[4]

- 1930: Honorary doctorate of law of the University of Vienna[4]

- 1930: Honorary doctorate of political science of the University of Graz[4]

Citations[]

- ^ Biografie.

- ^ Gehler 2007, p. 347.

- ^ Wandruszka 1983, p. 62.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Biografie, Bildungsweg.

- ^ Wandruszka 1983, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Wandruszka 1983, p. 63.

- ^ Biografie, Beruflicher Werdegang.

- ^ Wandruszka 1983, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Wandruszka 1983, p. 64.

- ^ Schemmel.

- ^ Wandruszka 1983, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Portisch 1989a, pp. 108–112.

- ^ Portisch 1989a, pp. 140–152.

- ^ Portisch 1989a, pp. 169–172.

- ^ Hoke 1996, p. 466.

- ^ Portisch 1989a, pp. 206–210.

- ^ Portisch 1989a, pp. 210–216.

- ^ Gehler 2007, p. 348.

- ^ Enderle-Burcel 1994, pp. 423–424.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Weyr 2005, p. 47.

- ^ Wandruszka 1983, pp. 62, 65, 70.

- ^ Orde 1980, p. 41.

- ^ Klemperer 1983, p. 102.

- ^ Wandruszka 1983, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Orde 1980, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Pelinka 1998, p. 11.

- ^ Portisch 1989a, pp. 310–311.

- ^ Portisch 1989a, pp. 286–293.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Wandruszka 1983, p. 66.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Schober I.

- ^ Portisch 1989a, pp. 297–298.

- ^ Portisch 1989a, pp. 298–299.

- ^ Portisch 1989a, pp. 298–302.

- ^ Portisch 1989a, p. 304.

- ^ Portisch 1989a, pp. 304–305.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Schober II.

- ^ Portisch 1989a, pp. 306–311.

- ^ Wandruszka 1983, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Interpol.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Enderle-Burcel 1994, p. 424.

- ^ Portisch 1989a, pp. 422, 424–426.

- ^ Portisch 1989a, pp. 423–424.

- ^ Portisch 1989a, pp. 426–427.

- ^ Portisch 1989a, pp. 438–439.

- ^ Portisch 1989a, pp. 439–448.

- ^ Portisch 1989a, p. 450.

- ^ Wandruszka 1983, p. 67.

- ^ Zohn 1997, p. 143.

- ^ Portisch 1989b, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Timms 2005.

- ^ Zohn 1997, pp. 143–145.

- ^ Wandruszka 1983, p. 65.

- ^ Hoke 1996, p. 470.

- ^ Portisch 1989b, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Neumüller 2011.

- ^ Presse, July 14, 2015.

- ^ Portisch 1989b, p. 32.

- ^ Brauneder 2009, pp. 213–215.

- ^ Pelinka 1998, pp. 7, 12–13.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Derbolav 2016.

- ^ Hoke 1996, pp. 469, 472.

- ^ Portisch 1989b, pp. 26–30.

- ^ Portisch 1989b, pp. 58–60.

- ^ Ackerl 1983, pp. 140, 142.

- ^ Portisch 1989b, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Ackerl 1983, pp. 141–142.

- ^ Portisch 1989b, pp. 57–60.

- ^ Portisch 1989b, p. 68.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wandruszka 1983, p. 68.

- ^ Schober III.

- ^ Portisch 1989b, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Portisch 1989b, pp. 71–73.

- ^ Wandruszka 1983, pp. 67–70.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Brauneder 2009, p. 215.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hoke 1996, p. 472.

- ^ Portisch 1989b, pp. 70–73.

- ^ Wandruszka 1983, p. 69.

- ^ Portisch 1989b, pp. 73–76.

- ^ Portisch 1989b, p. 76.

- ^ Wandruszka 1983, pp. 70–72.

- ^ Portisch 1989b, pp. 76–78.

- ^ Wandruszka 1983, p. 72.

- ^ Vaugoin.

- ^ Portisch 1989b, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Portisch 1989b, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Portisch 1989b, p. 81.

- ^ Wandruszka 1983, p. 73.

- ^ Portisch 1989b, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Ender.

- ^ Portisch 1989b, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Portisch 1989b, pp. 86–91.

- ^ Orde 1980, pp. 36–37, 49–51, 58.

- ^ Portisch 1989b, pp. 94–96.

- ^ Portisch 1989b, pp. 96, 97–98.

- ^ Orde 1980, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Orde 1980, p. 51.

- ^ Portisch 1989b, pp. 98–99.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Orde 1980, p. 34.

- ^ Portisch 1989b, p. 99.

- ^ Portisch 1989b, pp. 99–104.

- ^ Portisch 1989b, pp. 104, 106.

- ^ Buresch I.

- ^ Wandruszka 1983, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Wandruszka 1983, p. 74.

- ^ Portisch 1989b, p. 130.

References[]

English

- "History". Interpol. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- Orde, Anne (1980). "The Origins of the German-Austrian Customs Union Affair of 1931". Central European History. Cambridge University Press. 13 (1): 34–59. doi:10.1017/S0008938900008992. JSTOR 4545885.

- Pelinka, Peter (1998). Out of the Shadow of the Past. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-2918-5.

- Schemmel, B. "Johannes Schober". Rulers. Retrieved August 31, 2018.

- Timms, Edward (2005). Karl Kraus, Apocalyptic Satirist: The Post-war Crisis and the Rise of the Swastika. Volume 2. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10751-7.

|volume=has extra text (help) - Weyr, Thomas (2005). The Setting of the Pearl. Vienna under Hitler. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514679-0.

- Zohn, Harry (1997). Karl Kraus and the Critics. Camden House. ISBN 978-1-571-13181-2.

German

- Ackerl, Isabella (1983). "Ernst Streeruwitz". In Weissensteiner, Friedrich; Weinzierl, Erika (eds.). Die österreichischen Bundeskanzler. Vienna: Österreichischer Bundesverlag. ISBN 978-3-215-04669-8.

- "Biografie Johannes Schober". Austrian Parliament. Retrieved August 31, 2018.

- Brauneder, Wilhelm (2009). Österreichische Verfassungsgeschichte (11th ed.). Vienna: Manzsche Verlags- und Universitätsbuchhandlung. ISBN 978-3-214-14876-8.

- "Buresch I". Austrian Parliament. Retrieved September 2, 2018.

- Derbolav, Dietrich (November 26, 2016). "Österreich, eine "halbpräsidiale" Republik?". Der Standard. Retrieved August 17, 2018.

- "Ender". Austrian Parliament. Retrieved September 2, 2018.

- Enderle-Burcel, Gertrude (1994). Österreichisches Biographisches Lexikon 1815–1950. Band 10. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. ISBN 978-3-700-12186-2.

- Gehler, Michael (2007). Neue Deutsche Biographie. Band 23. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot. ISBN 978-3-428-11204-3.

- (1996). Österreichische und deutsche Rechtsgeschichte (2nd ed.). Vienna: Böhlau Studienbücher. ISBN 978-3-205-98179-4.

- Klemperer, Klemens (1983). "Ignaz Seipel". In Weissensteiner, Friedrich; Weinzierl, Erika (eds.). Die österreichischen Bundeskanzler. Vienna: Österreichischer Bundesverlag. ISBN 978-3-215-04669-8.

- Portisch, Hugo (1989a). Österreich I: Band 1: Die unterschätzte Republik. Vienna: Kremayr & Scheriau. ISBN 978-3-453-07945-8.

- Portisch, Hugo (1989b). Österreich I: Band 2: Abschied von Österreich. Vienna: Kremayr & Scheriau. ISBN 978-3-453-07946-5.

- Neumüller, Hermann (December 27, 2011). "Erfolgsgeschichte Schilling: Vom Notnagel zum Alpendollar". Oberösterreichische Nachrichten. Retrieved August 26, 2018.

- "Als Österreich eine Art Griechenland war". Die Presse. July 14, 2015. Retrieved August 26, 2018.

- "Schober I". Austrian Parliament. Retrieved August 31, 2018.

- "Schober II". Austrian Parliament. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- "Schober III". Austrian Parliament. Retrieved September 2, 2018.

- "Vaugoin". Austrian Parliament. Retrieved September 2, 2018.

- Wandruszka, Adam (1983). "Johannes Schober". In Weissensteiner, Friedrich; Weinzierl, Erika (eds.). Die österreichischen Bundeskanzler. Vienna: Österreichischer Bundesverlag. ISBN 978-3-215-04669-8.

Further reading[]

- Hannak, Jacques (1966). Johannes Schober. Mittelweg in die Katastrophe. Porträt eines Representanten der verlorenen Mitte. Vienna: Europa-Verlag.

- Hubert, Rainer (1990). Schober. "Arbeitermörder" und "Hort der Republik". Biographie eines Gestrigen. Vienna: Böhlau. ISBN 978-3-205-05341-5.

- Swanson, John Charles (2001). The Remnants of the Habsburg Monarchy: The Shaping of Modern Austria and Hungary, 1918–1922. Eastern European Monographs. ISBN 978-0-880-33466-2.

External links[]

- Johannes Schober CV on the website of the Austrian Parliament

- Newspaper clippings about Johannes Schober in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- Chancellors of Austria

- 1874 births

- 1932 deaths

- 20th-century Chancellors of Austria

- Austrian police officers

- Finance Ministers of Austria

- Foreign ministers of Austria

- Vice-Chancellors of Austria

- Interpol officials

- German nationalism in Austria

- Members of the National Council (Austria)

- Austrian civil servants

- 20th-century jurists

- Austrian jurists

- University of Vienna alumni

- People from Perg District