Flag of Chicago

| |

| Use | Civil flag |

|---|---|

| Proportion | 2:3 |

| Adopted | Original, 1917; additional stars added, 1933 and 1939. |

| Design | Argent four mullets of six points gules in fess between two bars bleu de ciel. |

| Designed by | Wallace Rice |

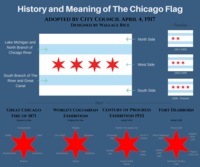

The flag of Chicago consists of two light sky blue horizontal bars, or stripes, on a field of white, each bar one-sixth the height of the full flag, and placed slightly less than one-sixth of the way from the top and bottom. Four bright red stars, with six sharp points each, are set side by side, close together, in the middle third of the surface of the flag.[1]

The City of Chicago's flag was adopted in 1917 after the design by Wallace Rice won a City Council sponsored competition. It initially had two stars, until 1933 when a third was added. The four-star version has existed since 1939. The three sections of the white field and the two bars represent geographical features of the city, the stars symbolize historical events, and the points of the stars represent important virtues or concepts. The historic events represented by the stars are the establishment of Fort Dearborn, the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893, and the Century of Progress Exposition of 1933–34.

In a review by the North American Vexillological Association of 150 American city flags, the Chicago city flag was ranked second best with a rating of 9.03 out of 10, behind only the flag of Washington, D.C.[2]

Symbolism[]

Bars[]

The three white background areas of the flag represent, from top to bottom, the North, West, and South sides of the city. The top blue bar represents Lake Michigan and the North Branch of the Chicago River. The bottom blue bar represents the South Branch of the river and the "Great Canal", over the Chicago Portage.[3] The light blue of the flag's two bars is variously called sky blue[4] or pale blue;[5] in a 1917 article of a speech by designer, Wallace Rice, it was called "the color of water".[6][7]

Stars[]

There are four red six-pointed stars on the center white bar. Six-pointed stars are used because five-pointed stars represent sovereign states, and because the star as designed was not found on any other known flags as of 1917.[9] From the hoist outwards, the stars represent:

- Added in 1939: Commemorates Fort Dearborn, and its six points stand for political entities the Chicago region has belonged to and the flags that have flown over the area: France, 1693; Great Britain, 1763; Virginia, 1778; the Northwest Territory, 1789; Indiana Territory, 1802; and Illinois (territory, 1809, and state, since 1818).[1][3]

- Original to the 1917 flag: This star stands for the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. Its six points represent the virtues of religion, education, aesthetics, justice, beneficence, and civic pride.[1][3]

- Original to the 1917 flag: This star symbolizes the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893. Its six points symbolize transportation, labor, commerce, finance, populousness, and salubrity (health).[1][3]

- Added in 1933: This star represents the Century of Progress Exposition (1933–34). Its points refer to: Chicago's status as the United States' second largest city at the time of the stars addition (Chicago became third largest in a 1990 census when passed by Los Angeles); Chicago's Latin motto, Urbs in horto ("City in a garden"); Chicago's "I Will" motto; the Great Central Marketplace; Wonder City; and Convention City.[1][3]

Additional stars have been proposed, with varying degrees of seriousness. The following reasons have been suggested for possible additions of a fifth star:

- A fifth star could represent Chicago's contribution to the nuclear age (see Metallurgical Laboratory), an idea first suggested in a 1940s letter published by the Chicago Tribune and later championed by Mayor Daley in the 1960s.[10][11][12]

- In the 1980s, a star was proposed in honor of Harold Washington, the first African-American mayor of Chicago.[12][13]

- The 1992 Chicago Flood was suggested as an additional natural disaster deserving of a star,[citation needed] in line with the existing star for the 1871 Great Chicago Fire. Another fifth star was in the works from a group of Chicago real estate professionals to represent Chicago's entrepreneurial spirit in the early 1990s.[citation needed]

- When Chicago was bidding to host the 2016 Summer Olympics, the Bid Committee proposed that a fifth star be added to the flag in commemoration,[12][14] but the bid was won instead by Rio de Janeiro.

- Anne Burke, Tim Shriver, and others have proposed adding a fifth star to commemorate the Special Olympics, which were founded in Chicago.[15][16]

- Other sports-related suggestions include recognizing the Chicago Bulls' dominance of the NBA in the 1990s[17] and a proposal for a fifth star if the Chicago Cubs should ever win the World Series,[17] which did not happen between their long drought of series wins in 1908, up to 2016.

- The Chicago History Museum has an ongoing exhibition where the public is encouraged to vote for a potential fifth star.[18]

- Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot suggested that Chicago's response to the COVID-19 pandemic could warrant adding a fifth star to Chicago's flag.[19]

Unlawful private use[]

Per the Municipal Code of Chicago, it is unlawful to use the flag, or any imitation or design thereof, except for the usual and customary purposes of decoration or display. Causing to be displayed on the flag any letter, word, legend, or device not provided for in the Code is also prohibited. Violators are subject to fines between $5.00 and $25.00 for each offense.[20] The constitutionality of such restrictions is questionable.

History[]

In 1915, Mayor William Hale Thompson appointed a municipal flag commission, chaired by Alderman . Among the commission members were wealthy industrialist Charles Deering and impressionist painter Lawton S. Parker. Parker asked lecturer and poet Wallace Rice to develop the rules for an open public competition for the best flag design. Over a thousand entries were received.[citation needed] The 318th Cavalry Regiment (United States) incorporated the flag into their insignia.[citation needed]

Sketches for the flag from a contest from 1892. This design ultimately became used in the municipal device.[21]

Twenty-three other icons that were commissioned representing different city departments that could be placed on the flag for that department.[22]

Chicago flag of 1917 poster, with "I Will" motto

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e City of Chicago (2020-03-18) [Originally published 1990.]. "1-8-030 Municipal flag – Design requirements". Municipal Code of Chicago (Municipal code.). American Legal Publishing Corporation. sec. 1-8-030. Archived from the original on 2020-06-08. Retrieved 2020-06-08 – via American Legal Publishing’s Code Library.

- ^ "2004 American City Flags Survey", North American Vexillological Association press release, 2 October 2004

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Chicago Facts: Municipal Flag". Chicago Public Library. Retrieved 2014-07-10.

- ^ "Chicago". Chicago magazine.

- ^ "Flying Colors: The Best and Worst of Flag Design". Print Magazine.

- ^ "Association Sounds Chicago's Call . . ". Chicago Commerce. Chicago Association of Commerce and Industry. December 6, 1917. p. 6.

- ^ Chicago's flag: The history of every star and every stripe, Chicago Tribune, 13 June, 2016

- ^ Marx, Kori Rumore and Ryan. "Chicago's flag: The history of every star and every stripe". chicagotribune.com. Retrieved 2019-04-07.

- ^ Rice, Wallace; T. E. Whalen (22 July 2005). "Wallace Rice on Chicago Stars". introvert.net. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ^ Heise, Kenan (August 15, 1976). "It's a grand old flag. But it could be grander". Chicago Tribune Magazine. p. 34. Retrieved April 14, 2017.

- ^ Whalen, T.E. (January 3, 2006), The Municipal Flag of Chicago: References (PDF), p. 8

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Konkol, Mark (June 30, 2015). "The Story of the Rare 5-Star Chicago Flag That Wasn't Supposed To Exist". My Chicago. DNAinfo. Archived from the original on June 14, 2017. Retrieved April 14, 2017.

- ^ "Please, A Moratorium On Memorials". Chicago Tribune. 23 December 1987. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

Ald. Raymond Figueroa and others want a fifth star added to the city's flag in memory of Mr. Washington.

- ^ Chicago 2016 Newswire (December 14, 2006), Chicago Students Creatively Try to Bring Home the Bid, Chicago 2016 Committee, archived from the original on February 10, 2007, retrieved April 14, 2017

- ^ "Anne Burke wants fifth star on Chicago flag for Special Olympics". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2018-07-20.

- ^ Janssen, Kim. "Add a fifth star to Chicago flag, Justice Anne Burke tells Emanuel". chicagotribune.com. Retrieved 2018-07-20.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rumore, Kori; Marx, Ryan (June 13, 2016). "Chicago's flag: The history of every star and every stripe". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved April 14, 2017.

- ^ https://www.chicagohistory.org/exhibition/the-fifth-star-challenge

- ^ https://news.wttw.com/2020/05/08/lightfoot-outlines-5-phase-plan-reopen-chicago

- ^ City of Chicago (2020-03-18) [Originally published 1990.]. "1-8-090 Private use of flags and emblems unlawful". Municipal Code of Chicago (Municipal code.). American Legal Publishing Corporation. sec. 1-8-090. Archived from the original on 2020-06-08. Retrieved 2020-06-08 – via American Legal Publishing’s Code Library.

- ^ Marx, Kori Rumore and Ryan. "Chicago's flag: The history of every star and every stripe". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2019-04-07.

- ^ Marx, Kori Rumore and Ryan. "Chicago's flag: The history of every star and every stripe". chicagotribune.com. Retrieved 2019-04-07.

Further reading[]

- "Art and Architecture: How the Chicago Municipal Flag Came to be Chosen", Chicago Daily Tribune, July 17, 1921, p. 21.

- "City Gets New Flag Today with Third Star for 1933 Fair", Chicago Daily Tribune, October 9, 1933, p. 7.

- "Fort Dearborn Gets a Star on Chicago's Flag", Chicago Daily Tribune, December 22, 1939. p. 18.

External links[]

- Chicago

- Flags of cities in the United States

- Flags of Illinois

- Government of Chicago

- Flags introduced in 1917

- 1917 establishments in Illinois