Flora Antarctica

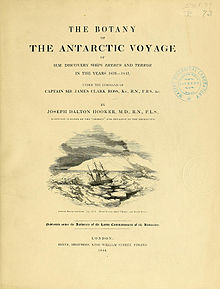

Title page with an etching of Victoria Barrier with Mount Erebus and Mount Terror; one of the expedition's ships is shown temporarily trapped in sea ice. | |

| Author | Joseph Dalton Hooker |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Walter Hood Fitch |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Series | Monthly parts |

| Subject | Botany |

| Publisher | Reeve Brothers |

Publication date | 1843–1859 |

| Text | Flora Antarctica at Wikisource |

The Flora Antarctica, or formally and correctly The Botany of the Antarctic Voyage of H.M. Discovery Ships Erebus and Terror in the years 1839–1843, under the Command of Captain Sir James Clark Ross, is a description of the many plants discovered on the Ross expedition, which visited islands off the coast of the Antarctic continent, with a summary of the expedition itself, written by the British botanist Joseph Dalton Hooker and published in parts between 1844 and 1859 by Reeve Brothers in London. Hooker sailed on HMS Erebus as assistant surgeon.[1]

The botanical findings of the Ross expedition were published in four parts, the last two in two volumes each, making six volumes in all:

- Part I Flora of Lord Auckland and Campbell's Islands (1843–1845)

- Part II Flora of Fuegia, the Falklands, Kerguellen's land, etc (1845–1847)

- Part III Flora of New Zealand (1851–1853) (2 volumes)

- Part IV Flora of Tasmania (1853–1859) (2 volumes)

All were "splendidly" illustrated by Walter Hood Fitch. The greater part of the plant specimens collected during this expedition are now part of the Kew Herbarium.[2]

Although Hooker professed not to have changed his views on the naturalist Charles Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection, the Flora of Tasmania contains an introductory essay on biogeography written from a Darwinian point of view, making the book the first case study for the theory.

Context[]

Ross expedition[]

The British government fitted out an expedition led by the explorer and naval officer James Clark Ross to investigate magnetism and marine geography in high southern latitudes, which sailed with two ships, HMS Terror and HMS Erebus on 29 September 1839 from Chatham.[3]

The ships docked at Madeira, Tenerife, the Cape Verde archipelago, Saint Peter and Saint Paul Archipelago, Trinidad to arrive at the Cape of Good Hope on 4 April 1840. On 21 April the giant kelp Macrocystis pyrifera was found off Marion Island, but no landfall could be made there or on the Crozet Islands due to the harsh winds. On 12 May the ships anchored at Christmas Harbour for two and a half months, during which all plants previously encountered by James Cook on the Kerguelen Islands were collected. On 20 July they sailed again to arrive on 16 August at the River Derwent, to remain in Tasmania until 12 November. A week later the flotilla stopped at Lord Auckland's Islands and Campbell's Island for the spring months.[3]

Large floating forests of Macrocystis and Durvillaea were found until the ships run into the icebergs at latitude 61° S. Pack-ice was met at 68° S and longitude 175°. During this part of the voyage Victoria Land, Mount Erebus and Mount Terror were discovered. After returning to Tasmania for three months, the flotilla went via Sydney to the Bay of Islands, and stayed for three months in New Zealand to collect the plants.[3]

From 6 April 1842 a long stay in the Falklands began, where the flora was investigated to supplement the work of Admiral D’Urville and of the crew of the Uranie. When visiting the Hermite Islands, seedlings of the deciduous Nothofagus antarctica and the evergreen Nothofagus betuloides were collected from this southernmost location of any tree. These were planted on the Falklands, and some were later brought to Kew. On Cockburn's Island twenty cryptogam species were found. The ships returned to the Cape of Good Hope on 4 April 1843. At the end of the journey specimens of some fifteen hundred plant species had been collected and preserved.[3]

Joseph Dalton Hooker[]

Joseph Dalton Hooker was a British botanist. His father, William Jackson Hooker, was the director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, the United Kingdom's centre for the study of plant species. The voyage to the Antarctic on the Ross Expedition, when he was 23 years old, was his first;[4] formally, he sailed on HMS Erebus as assistant surgeon.[1]He subsequently made voyages to regions around the world including the Himalayas and India in 1847–1851, Palestine in 1860, Morocco in 1871, and the Western United States in 1877, collecting plants and writing monographs on his findings in each case.[5] These helped him to build a high scientific reputation, and in 1855 he became Assistant-Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; he became full Director in 1865, remaining so for 20 years.[6]

Walter Hood Fitch[]

Hooker was ably assisted by the illustrator Walter Hood Fitch, who "splendidly" prepared the many colour illustrations required for the Flora.[2] William Jackson Hooker had encouraged Fitch to move into botanical illustration; from 1834, Fitch was the sole artist for Curtis's Botanical Magazine. In 1841, when William Jackson Hooker became Director at Kew, Fitch became Kew's sole artist for all its publications, making the chromolithographs by drawing directly onto the lithographic stone; Hooker paid him personally.[7][8]

Monograph[]

The four parts of the Flora Antarctica total 6 volumes, describe about 3000 species, and contain 530 plates which figure 1095 of the species. They were published by Reeve Brothers in London.

Approach[]

This section is empty. You can help by . (January 2022) |

Flora of Lord Auckland and Campbell's Islands[]

Part I, published between 1843 and 1845, covers the Flora of Lord Auckland and Campbell's Islands. It has 208 pages, 370 species, 80 plates and map, and figures 150 species.

Hooker was the first to study the sub-Antarctic Campbell Island and the Auckland group.[9]

Flora of Fuegia, the Falklands, Kerguellen's land, etc.[]

Part II, published between 1845 and 1847, covers the Flora of Fuegia, the Falklands, Kerguellen's land, etc. It has 366 pages, 1000 species, 120 plates, and figures 220 species.

According to Hooker, the flora of New Zealand's Antarctic islands is so different from that of the remainder of the territories visited during the voyage, that it merits a separate description. An exemplary difference is the dominance of Asteraceae in New Zealand's islands, and absence of representatives of the Rubiaceae, while the reverse is true for those two plant families on the other Antarctic archipelagos. So the Flora Antarctica describes in its second part the plants of Tierra del Fuego and the south-western coast of Patagonia, the Falkland Islands, Palmer's Land, South Shetlands, South Georgia, Tristan da Cunha, and Kerguellen's Land.[10]

Flora Novae-Zelandiae[]

Part III, the Flora of New Zealand or Flora Nova-Zelandiae, was published in two volumes between 1851 and 1853.

- Volume 1 Phanerogams (355 pages, 730 species, 70 plates, 83 species figured)

- Volume 2 Cryptogams (378 pages, 1037 species, 60 plates, 230 species figured)

The Flora "largely completed" the "primary phase of botanical survey in the [New Zealand] region".[9]

Flora Tasmaniae[]

Part IV, the Flora of Tasmania or Flora Tasmaniae was published in two volumes between 1853 and 1859.

- Volume 1 Dicotyledones (550 pages, 758 species, 100 plates, 138 species figured)

- Volume 2 Monocotyledones and Acotyledones (422 pages, 1445 species, 100 plates, 274 species figured)

Hooker dedicated this Part to the local Tasmanian naturalists Ronald Campbell Gunn and William Archer, noting that "This Flora of Tasmania .. owes so much to their indefatigable exertions". Although the book is sometimes stated to have been published in 1859, the dedication is dated January 1860. It made use of plants collected by the local naturalist Robert Lawrence as well as Gunn and Archer.[11]

The book begins with an "Introductory Essay" on biogeography. It is followed by a "Key to the Natural Orders of Tasmanian Flowering Plants" and a more detailed key to the genera. The Flora proper begins with the first order, the Ranunculaceae.[citation needed]

Flora Tasmaniae was "the first published case study supporting Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection".[11] It contained a "milestone essay on biogeography",[12] "one of the first major public endorsements of the theory [of evolution by natural selection]".[13] Hooker gradually changed his mind on evolution as he wrote up his findings from the Ross expedition. While he asserted that "my own views on the subjects of the variability of existing species" remain "unaltered from those which I maintained in the 'Flora of New Zealand'", the Flora Tasmaniae is written from a Darwinian perspective that effectively assumes natural selection, or as Hooker named it, the "variation" theory, to be correct.[14]

Gallery[]

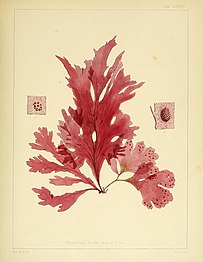

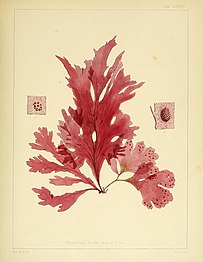

Nitophyllum smithi

Veronica benthami

Pleurophyllum speciosum

Stereocaulon ramulosum and Cenomyce aggregata

Nafsauvia serpens

Myzodendron brachystachum

Reception[]

Contemporary[]

The American botanist Asa Gray welcomed the publication of the first two parts of the Flora, describing it as an "elaborate and highly beautiful work,—second in importance and in perfection of illustration, to no other Flora which has appeared in our time".[15]

The work's author, Hooker, gave Charles Darwin a copy of (a draft of) the Flora; Darwin thanked him, and agreed in November 1845 that the geographical distribution of organisms would be "the key which will unlock the mystery of species".[16] To explain the presence of plant groups on the widely-separated landmasses of Australia, New Zealand, and southern South America, Hooker proposed that the groups indeed had common ancestors, and that the plants had spread across now-vanished land bridges. Darwin was sceptical of the explanation, preferring the hypothesis of long-distance seed dispersal.[17] For this work, Hooker has been described as "the real founder of causal historical biogeography".[18]

Modern[]

The book remains important, and continues to be cited in modern botanical research. For example, in 2013 W. H. Walton in his Antarctica: Global Science from a Frozen Continent describes it as "a major reference to this day", encompassing as it does "all the plants he found both in the Antarctic and on the sub-Antarctic islands", surviving better than Ross's deep-sea soundings which were made with "inadequate equipment".[19]

References[]

- ^ a b "The Erebus voyage". Kew Royal Botanic Gardens. Archived from the original on 23 November 2015. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ a b Goyder, David; Griggs, Pat; Nesbitt, Mark; Parker, Lynn; Ross-Jones, Kiri (2012). "Sir Joseph Hooker's Collections at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew" (PDF). Curtis's Botanical Magazine. 29 (1): 66–85. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8748.2012.01772.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 June 2015.

- ^ a b c d Hooker, Joseph Dalton (1844). Flora Antarctica, Volume 1, Parts 1-2, Flora Novae-Zelandiae. pp. v–vii.

- ^ Mills, Virginia (6 March 2016). "The rediscovery of the HMS 'Erebus' and the Joseph Hooker connection". Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ Anon. "Joseph Hooker the traveller". Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ Jones, Cam Sharp (23 June 2017). "Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker: trailblazing global botanist and explorer". Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ Curtis, Winifred M. (1972). Hooker, Sir Joseph Dalton (1817-1911). Australian Dictionary of Biography (Volume 4). MUP.

- ^ "Plants and Gardens portrayed". LuEsther T. Mertz Library. New York Botanical Garden. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ a b Frodin, David G. (14 June 2001). Guide to Standard Floras of the World: An Annotated, Geographically Arranged Systematic Bibliography of the Principal Floras, Enumerations, Checklists and Chorological Atlases of Different Areas. Cambridge University Press. p. 385. ISBN 978-1-139-42865-1.

- ^ Hooker, Joseph Dalton (1844). Flora Antarctica, Volume 1, Parts 1-2, Flora Novae-Zelandiae. pp. 209–223.

- ^ a b Cave, E. C. (2012). Flora Tasmaniae: Tasmanian naturalists and imperial botany, 1829-1860. University of Tasmania (PhD Thesis).

- ^ "Hooker, Joseph D. (1817 - 1911)". Australian National Herbarium. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ^ Ruse, Michael; Travis, Joseph (2009). Evolution: The First Four Billion Years. Harvard University Press. p. 639. ISBN 978-0-674-03175-3.

- ^ Endersby, Jim. "What Made Darwinism Useful to Joseph Dalton Hooker?". Victorian Web. Retrieved 29 February 2016. Extracted from the conclusion of Imperial Nature: Joseph Hooker and the Practices of Victorian Science, University of Chicago Press, 2008.

- ^ Gray, Asa (September 1849). "ART. XII.--Notice of Dr. Hooker's Flora Antarctica;". American Journal of Science and Arts. 8 (23): 161.

- ^ Darwin, Charles. "Letter from Darwin, C. R. to Hooker, J. D. on [5 or 12 Nov 1845] (MS DAR 114: 45, 45b)". University of Cambridge. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- ^ Winkworth, Richard C. (2010). "Darwin and dispersal" (PDF). Biology International. 47: 139–144.

- ^ Brundin, L. Z. (1990). "Phylogenetic biogeography". Analytical Biogeography. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. pp. 343–369. doi:10.1007/978-94-009-0435-4_11. ISBN 978-0-412-40050-6.

- ^ Walton, D. W. H. (2013). Antarctica: Global Science from a Frozen Continent. Cambridge University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-107-00392-7.

External links[]

- Volume 1 on Archive.org

- Colour Plates on Archive.org

- All volumes at Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Illustrations from 7 volumes: 1, 1(1), 1(2), 2(1), 2(2), 3(1), 3(2)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Flora Antarctica (Hooker). |

- Florae (publication)

- Flora of the Antarctic

- Books about Antarctica