Florida panther

| Florida panther | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | Felinae |

| Genus: | Puma |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | P. c. couguar

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Puma concolor couguar Kerr, 1792

| |

| |

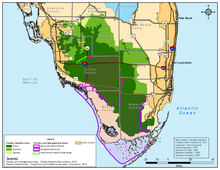

| Florida panther range[2] | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The Florida panther is a North American cougar (P. c. couguar) population[3] found in South Florida. It lives in pinelands, tropical hardwood hammocks, and mixed freshwater swamp forests.

Males can weigh up to 73 kg (161 lb)[4] and live within a range that includes the Big Cypress National Preserve, Everglades National Park, the Florida Panther National Wildlife Refuge, Picayune Strand State Forest, rural communities of Collier County, Florida, Hendry County, Florida, Lee County, Florida, Miami-Dade County, Florida, and Monroe County, Florida.[5][6] It is the only confirmed cougar population in the eastern United States, and currently occupies 5% of its historic range.[7] In the 1970s, an estimated 20 Florida panthers remained in the wild,[8] but their numbers had increased to an estimated 230 by 2017.[9]

In 1982, the Florida panther was chosen as the Florida state animal.[10]

Description[]

Florida panthers are spotted at birth, and typically have blue eyes. As the panther grows, the spots fade and the coat becomes completely tan, while the eyes typically take on a yellow hue. The panther's underbelly is a creamy white, and it has black tips on the tail and ears. Florida panthers lack the ability to roar, and instead make distinct sounds that include whistles, chirps, growls, hisses, and purrs. Florida panthers are average-sized for the species, being smaller than cougars from colder climates, but larger than cougars from the neotropics. Adult female Florida panthers weigh 29–45.5 kg (64–100 lb), whereas the larger males weigh 45.5–72 kg (100–159 lb). Total length is from 1.8 to 2.2 m (5.9 to 7.2 ft) and shoulder height is 60–70 cm (24–28 in).[11][12] Male panthers, on average, are 9.4% longer and 33.2% heavier than females because males grow at a faster rate than females and for a longer time.[13]

Taxonomic status[]

It was described as a distinct cougar subspecies (Puma concolor coryi) in the late 19th century.[14] The Florida panther had for a long time been considered a unique cougar subspecies, with the scientific name Felis concolor coryi proposed by Outram Bangs in 1899.[14] A genetic study of cougar mitochondrial DNA showed that many of the purported cougar subspecies described in the 19th century are too similar to be recognized as distinct.[15] It was reclassified and subsumed to the North American cougar (P. c. couguar) in 2005.[14] Despite these findings, it was still referred to as a distinct subspecies P. c. coryi in 2006.[16]

In 2017, the Cat Classification Taskforce of the Cat Specialist Group revised the taxonomy of Felidae, and now recognises all cougar populations in North America as P. c. couguar.[3]

Diet[]

The Florida panther is a large carnivore whose diet consists both of small animals, such as raccoons, armadillos, nutrias, hares, mice, and waterfowl, and larger prey such as storks, white-tailed deer, feral pigs, and small American alligators. The Florida panther is an opportunistic hunter, and has been known to prey on livestock and domesticated animals, including cattle, goats, horses, pigs, sheep, chickens, dogs, and cats.[17] When hunting, panthers shift their hunting environment based on where the prey base is. Female panthers frequently shift both their home range and movement behavior due to their reproductive rates.[18][19] [20][21]

Early life[]

Panther kittens are born in dens created by their mothers, often in dense scrub. The dens are chosen based on a variety of factors, including prey availability, and have been observed in a range of habitats. Kittens will spend the first 6–8 weeks of life in those dens, dependent on their mother.[22] In the first 2–3 weeks, the mother spends most of her time nursing the kittens; after this period, she spends more time away from the den, to wean the kittens and to hunt prey to bring to the den. Once they are old enough to leave the den, they hunt in the company of their mother. Male panthers are not encountered frequently during this time, as female and male panthers generally avoid each other outside of breeding. Kittens are usually 2 months old when they begin hunting with their mothers, and 2 years old when they begin to hunt and live on their own.[18]

Threats[]

Humans threaten the Florida panther through poaching and wildlife control measures. Besides predation, the biggest threat to the Florida panther is habitat fragmentation. It was persecuted, and the population reduced to a small area in southern Florida. The population became inbred with individuals having kinked tails, and heart and sperm problems.[23]

The two highest causes of mortality for individual Florida panthers are automobile collisions and territorial aggression between Florida panthers.[24] When these incidents injure the panthers, federal and Florida wildlife officials take them to White Oak Conservation in Yulee, Florida, for recovery and rehabilitation until they are well enough to be reintroduced.[25] Additionally, White Oak raises orphaned kittens and has done so for 12 individuals. Most recently, an orphaned brother and sister were brought to the center at 5 months old in 2011 after their mother was found dead in Collier County, Florida.[26] After being raised, the male and female were released in early 2013 to the Rotenberger Wildlife Management Area and Collier County, respectively.[27]

Primary threats to the population as a whole include habitat loss, habitat degradation, and habitat fragmentation. Southern Florida is a fast-developing area, and certain developments such as Ave Maria near Naples, are controversial for their location in prime panther habitat.[28] Fragmentation by major roads has severely segmented the sexes of the Florida panther, as well. In a study done between 1981 and 2004, most panthers involved in car collisions were found to be male. However, females are much more reluctant to cross roads. Therefore, roads separate habitat, and adult panthers.[29]

Development, as well as the Caloosahatchee River, are major barriers to natural population expansion.[30] While young males wander over extremely large areas in search of an available territory, females occupy home ranges close to their mothers. For this reason, panthers are poor colonizers and expand their range slowly, despite occurrences of males far away from the core population.

Disease[]

Antigen analysis on select Florida panther populations has shown evidence of feline immunodeficiency virus and puma lentivirus among certain individuals. The presence of these viruses is likely related to mating behaviors and territory sympatry. Although, since Florida panthers have lower levels of the antibodies produced in response to FIV, consistently positive results for the presence of infection is difficult to find.[31]

In the 2002–2003 capture season, feline leukemia virus was first observed in two panthers. Further analysis determined an increase in FeLV-positive panthers from January 1990 to April 2007. The virus is lethal, and its presence has resulted in efforts to inoculate the population. While no new cases have been reported since July 2004, the virus does have potential for reintroduction.[32]

In August 2019, Florida's Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission identified, through the use of game cameras, eight endangered panthers affected by an apparent neurological disorder, but were unable to identify any potential infectious diseases that can affect felines and other species.[33][34]

Chemicals[]

Exposure to a variety of chemical compounds in the environment has caused reproductive impairment to Florida panthers. Tests show that the differences between males and females in estradiol levels are insignificant, which suggests that males have been feminized due to chemical exposure. Feminized males are much less likely to reproduce, which represents a significant threat to a subspecies that already has a low population count and a high level of inbreeding. Chemical compounds that have created abnormalities in Florida panther reproduction include herbicides, pesticides, and fungicides such as benomyl, carbendazim, chlordecone, methoxychlor, methylmercury, fenarimol, and TCDD.[35]

Genetic depletion[]

The Florida panther has low genetic diversity due to a variety of environmental and genetic factors. Factors that include habitat destruction contributed to the formation of a distinct and isolated subspecies of puma in the Florida panther. Isolation was followed by a gradual decline in the population size that increased the likelihood of inbreeding depression.[36] The lower genetic diversity and higher rates of inbreeding led to the increased expression of deleterious traits in the populations, resulting in lower overall fitness of the Florida panther population. This also lowers the adaptive capacity of the population and increases the likelihood of genetic defects[37] such as cryptorchidism and other complications to the heart and immune system. Specifically concerning the Florida panther, one of the morphological consequences of inbreeding was a high frequency of cowlicks and kinked tails. The frequency of exhibiting a cowlick in a Florida panther population was 94% compared to other pumas at 9%, while the frequency of a kinked tail was 88% as opposed to 27% for other puma subspecies.[38] To increase genetic diversity of the Florida panther, eight Texas pumas were introduced to the Florida population to hopefully promote the survival of the native population. The results indicated that the survival rates of hybrid kittens were three times higher than those of purebred pumas.[36] Due to the successes of this restoration effort, the genetic depletion of the Florida panther population is now not as much of a problem as it used to be, but ought to be monitored since the population is still in a fragile state.

Vehicular collisions[]

Florida panthers live in home ranges between 190 and 500 km2. Within these ranges are many roads and human constructions, which are regularly traveled on by Florida panthers and can result in their death by vehicular collision. Efforts to reduce collisions with the Florida panther include nighttime speed reduction zones, special roadsides, headlight reflectors, and rumble strips. Another method of reducing collisions is the creation of wildlife corridors. Because wildlife corridors emulate the natural environment, animals are more likely to cross through a corridor rather than a road because a corridor provides more cover for prey and predators, and is safer to cross than a road.[38]

Conservation status[]

It was formerly considered critically endangered by the IUCN, but it has not been listed since 2008. Recovery efforts are currently underway in Florida to conserve the state's remaining population of native panthers. This is a difficult task, as the panther requires contiguous areas of habitat – each breeding unit, consisting of one male and two to five females, requires about 200 square miles (500 km2) of habitat.[39] This animal is considered to be a conservational flagship because it is a major contributor to the keystone ecological and evolutionary processes in their environment.[21] A population of 240 panthers would require 8,000–12,000 square miles (21,000–31,000 km2) of habitat and sufficient genetic diversity to avoid inbreeding as a result of small population size. However, a study in 2006 estimated that about 3,800 square miles (9,800 km2) were free for the panthers.[40] The introduction of eight female cougars from a closely related Texas population has apparently been successful in mitigating inbreeding problems.[41][42] One objective to panther recovery is establishing two additional populations within historic range, a goal that has been politically difficult.[43]

Outside Florida[]

Florida panthers, usually wandering males, have occurred as vagrants outside of Florida. In 2008, a Georgia man was sentenced to 2 years probation, fined, and handed a lifetime hunting ban for killing a Florida panther that had walked 600 miles north to Troup County, Georgia.[44][45] In about 2014, a male panther was shot and killed in the Okefenokee Swamp in Georgia.[46]

Habitat Conservation[]

The conservation of Florida panther habitats is especially important because they rely on the protection of the forest, specifically hardwood hammock, cypress swamp, pineland, and hardwood swamp, for their survival.[21] Conservations strategies for Florida panthers tend to focus on their preferred morning habitats. However, GPS tracking has determined that habitat selection for panthers varies by time of day for all observed individuals, regardless of size or gender. They move from wetlands during the daytime, to prairie grasslands at night. The implications of these findings suggest that conservation efforts be focused on the full range of habitats used by Florida panther populations.[47] Female panthers with cubs build dens for their litters in an equally wide variety of habitats, favoring dense scrub, but also using grassland and marshland.[22]

Management controversy[]

In 2003, a controversy began involving the leading Florida panther expert David Maehr. He was covertly paid by land developers to produce faulty science papers that were used to permit construction projects that destroyed Florida panther habitat.[48][49]

In light of accusations against Maehr's work, recovery agencies appointed a panel of four experts, the Florida Panther Scientific Review Team (SRT), to evaluate the soundness of the body of work used to guide panther recovery. The SRT identified serious problems with Maehr's literature, including poor citations and misrepresentation of data to support unsound conclusions.[50][51][52] A Data Quality Act (DQA) complaint brought by Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility and Andrew Eller, a biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), was successful in demonstrating that agencies continued to use incorrect information after it had been clearly identified as such.[53] As a result of the DQA ruling, USFWS admitted errors in the science the agency was using and subsequently reinstated Eller, who had been fired by USFWS after filing the DQA complaint. In two white papers, environmental groups contended that habitat development was permitted that should not have been, and documented the link between incorrect data and financial conflicts of interest.[54][55]

David Maehr was covertly paid by developers and as a result of his faulty science research gave developers the necessary permitting to clear forests otherwise needed by the panthers to retains a viable breeding population.[48] In January 2006, USFWS released a new draft Florida Panther Recovery Plan for public review.[56] The discredited Maehr left Florida and the field of panthers to study black bears in Kentucky; he died in a plane accident in 2008, while doing bear research.[48]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ "Florida Panther". National Wildlife Refuge System. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey (2017). "Florida Panther (Puma concolor coryi) mCOUGc_CONUS_2001v1 Range Map". Gap Analysis Project. doi:10.5066/F7FJ2FVH.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kitchener, A. C.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Eizirik, E.; Gentry, A.; Werdelin, L.; Wilting, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Abramov, A. V.; Christiansen, P.; Driscoll, C.; Duckworth, J. W.; Johnson, W.; Luo, S.-J.; Meijaard, E.; O’Donoghue, P.; Sanderson, J.; Seymour, K.; Bruford, M.; Groves, C.; Hoffmann, M.; Nowell, K.; Timmons, Z.; Tobe, S. (2017). "A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group" (PDF). Cat News. Special Issue 11: 33–34.

- ^ "Florida Panther General Information". Florida Panther Society. Archived from the original on 2015-09-14. Retrieved 2010-12-24.

- ^ Range of the Puma. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. Last Retrieved 2017-06-24

- ^ FLORIDA PANTHER. Division of Endangered Species, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Last Retrieved 2007-01-30. Archived April 27, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Florida Panther - U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service". www.fws.gov. Archived from the original on 2020-06-29. Retrieved 2020-10-15.

- ^ "msnbc.com Video Player". NBC News. Retrieved 2011-10-13.

- ^ FWC Florida Panther. myfwc.com June 24, 2017

- ^ Florida Department of State (2015). "State Animal: Florida Panther". dos.myflorida.com. Tallahassee, Florida, US: State of Florida, Florida Department of State. Archived from the original on 2015-01-22. Retrieved 2015-03-28.

Much folklore surrounds these seldom-seen cats, sometimes called 'catamounts' or 'painters,' and they have been persecuted out of fear and misunderstanding of the role these large predators play in the natural ecosystem

- ^ WEC 167/UW176: Jaguar: Another Threatened Panther. Edis.ifas.ufl.edu. Retrieved on 2012-05-02.

- ^ PantherNet : Handbook: Natural History : Physical Description. Floridapanthernet.org. Retrieved on 2012-05-02.

- ^ Bartareau, Tad; Onorato, Dave; Jansen, Deborah (March 2013). "Growth in body length and mass of the Florida panther: An evaluation of different models and sexual size dimorphism". Southeastern Naturalist. 12 (1): 27–40. doi:10.1656/058.012.0103. S2CID 85220716.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Subspecies Puma concolor couguar". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 544–545. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Culver, M.; Johnson, W.E.; Pecon-Slattery, J.; O'Brein, S.J. (2000). "Genomic Ancestry of the American Puma" (PDF). Journal of Heredity. 91 (3): 186–197. doi:10.1093/jhered/91.3.186. PMID 10833043.

- ^ Conroy, M. J.; Beier, P.; Quigley, H.; Vaughan, M. R. (2006). "Improving The Use Of Science In Conservation: Lessons From The Florida Panther". Journal of Wildlife Management. 70 (1): 1–7. doi:10.2193/0022-541X(2006)70[1:ITUOSI]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ [1]. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. Last Retrieved 2017-07-14

- ^ Jump up to: a b Maehr, D.S.; Land, E. Darrell; Roof, Jayde C.; McCown, J. Walter (July 1989). "Early maternal behavior in the Florida panther". The American Midland Naturalist. 122 (1): 34–43. doi:10.2307/2425680. JSTOR 2425680.

- ^ Kilgo, J. E. (1998). "Influences of Hunting on the Behavior of White-Tailed Deer: Implications for Conservation of the Florida Panther" (PDF). Conservation Biology. 12 (6): 1359–1365. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1998.97223.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-11-07. Retrieved 2014-11-07.

- ^ McBride, Roy; McBride, Cougar (December 2010). "Predation of a Large Alligator by a Florida Panther". Southeastern Naturalist. 9 (4): 854–856. doi:10.1656/058.009.0420. S2CID 85338748.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Maehr, David S.; Deason, Jonathan P. (2014). "Wide-ranging carnivores and development permits: constructing a multi-scale model to evaluate impacts on the Florida panther". Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy. 3 (4): 398–406. doi:10.1007/s10098-001-0129-4. S2CID 98146689.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Benson, John F.; Lotz, Mark A.; Jansen, Deborah (February 2008). "Natal Den Selection by Florida Panthers". Journal of Wildlife Management. 72 (2): 405–410. doi:10.2193/2007-264. S2CID 86458097.

- ^ Silverstein, A. (1997). The Florida Panther. Brooksville, Connecticut: Millbrook Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-7613-0049-6.

- ^ "The Florida Panther". Sierra Club Florida. Archived from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- ^ "BACK TO THE WILD". Friends of the Florida Panther Refuge. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- ^ Staats, Eric (23 September 2011). "Orphaned Florida panther kittens rescued". Naples Daily News.

- ^ Fleshler, David (3 April 2013). "First Florida panther released into Palm Beach County". Sun Sentinel.

- ^ Staats, Eric (January 27, 2004). "Sierra Club Says Ave Maria Will 'Threaten' Everglades". Naples Daily News. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ^ Schwab, Autumn; Paul Zandbergen (April 2011). "Vehicle-related mortality and road crossing behavior of the Florida Panther". Applied Geography. 31 (2): 859–870. doi:10.1016/j.apgeog.2010.10.015.

- ^ Newborn, Steve (May 23, 2021). "Once Nearly Extinct, The Florida Panther Is Making A Comeback". NPR News. Retrieved 2021-05-24.

- ^ Miller, D.L.; Taylor, Rotstein; Pough, Barr (April 2006). "Feline Immunodeficiency Virus and Puma Lentivirus in Florida panthers (Puma concolor coryi): Epidemiology and Diagnostic Issues". Veterinary Research Communications. 30 (3): 307–317. doi:10.1007/s11259-006-3167-x. PMC 7089169. PMID 16437306.

- ^ Cunningham, Mark W.; Brown, Meredith A.; Shindle, David B.; Terrell, Scott P.; Hayes, Kathleen A.; Ferree, Bambi C.; McBride, R. T.; Blankenship, Emmett L.; Jansen, Deborah; Citino, Scott B.; Roelke, Melody E.; Kiltie, Richard A.; Troyer, Jennifer L.; O'Brien, Stephen J. (2008). "Epizootiology and Management of Feline Leukemia Virus in the Florida Puma". Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 44 (3): 537–552. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-44.3.537. PMC 3167064. PMID 18689639.

- ^ Sokol, Joshua (2019-08-20). "Florida's Panthers Hit With Mysterious Crippling Disorder". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-08-21.

- ^ "A neurological disorder is impacting panthers in Florida making it hard for them to walk". www.msn.com. Retrieved 2019-08-21.

- ^ Facemire, Charles; Gross, Guillette (May 1995). "Reproductive Impairment in the Florida Panther: Nature or Nurture?". Environmental Health Perspectives. 103 (Supplement 4): 79–86. doi:10.2307/3432416. JSTOR 3432416. PMC 1519283. PMID 7556029.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pimm, S. L.; Dollar, L.; Bass, O. L. (2006-05-01). "The genetic rescue of the Florida panther". Animal Conservation. 9 (2): 115–122. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1795.2005.00010.x. ISSN 1469-1795. S2CID 53059157.

- ^ Kardos, Marty; Taylor, Helen R.; Ellegren, Hans; Luikart, Gordon; Allendorf, Fred W. (2016-12-01). "Genomics advances the study of inbreeding depression in the wild". Evolutionary Applications. 9 (10): 1205–1218. doi:10.1111/eva.12414. ISSN 1752-4571. PMC 5108213. PMID 27877200.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Land, Darrell; Lotz (1996). "Wildlife Crossing Designs and Use by Florida Panthers and Other Wildlife in Southwest Florida" (PDF). Trends in Addressing Transportation Related Wildlife Mortality. p. 323.

- ^ Florida Panther Recovery Plan Archived 2006-10-02 at the Wayback Machine. The Florida Panther Recovery Team, South Florida Ecological Services Office, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Published 1995-03-13. Retrieved 2007-01-30.

- ^ Kautz, Randy (June 2006). "How much is enough? Landscape-scale conservation for the Florida panther". Biological Conservation. 130 (1): 118–133. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2005.12.007.

- ^ Florida panther | Section : Historic Range . . . U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

- ^ The genetic rescue of the Florida panther, 2005 pdf, George Washington University

- ^ Pittman, Craig (December 18, 2008). "Florida panthers need new territory, federal officials say". Tampa Bay Times. St. Petersburg, FL. Archived from the original on October 5, 2013. Retrieved 2013-08-20.

- ^ Terry Dickson (August 5, 2011). "Georgia man who killed Florida panther gets two years probation, banned from hunting". The Florida Times-Union. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ Dean Kui (2017). "The Panther You Want". Orion Magazine. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ Dexter Filkins (May 29, 2017). "The Return of the Florida Panther". The New Yorker. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ Onorato, D. P.; Criffield, M.; Lotz, M.; Cunningham, M.; McBride, R.; Leone, E. H.; Bass, O. L.; Hellgren, E. C. (April 2011). "Habitat selection by critically endangered Florida panthers across the diel period: implications for land management and conservation". Animal Conservation. 14 (11): 196–205. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1795.2010.00415.x.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Craig Pittman (2020). "Ch. 14-18". Cat Tale: The Wild, Weird Battle to Save the Florida Panther. Hanover Square Press. ISBN 978-1335938800.

- ^ Gross L (2005). "Why Not the Best? How Science Failed the Florida Panther". PLOS Biol. 3 (9): e333. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030333. PMC 1188244. PMID 16108700.

- ^ Beier, P; Vaughan, MR; Conroy, MJ and Quigley, H. 2003, An analysis of scientific literature related to the Florida panther: Submitted as final report for Project NG01-105 Archived 2006-09-02 at the Wayback Machine, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Tallahassee, FL.

- ^ Beier, P; Vaughan, MR; Conroy, MJ; Quigley, H (2006). "Evaluating scientific inferences about the Florida panther" (PDF). Journal of Wildlife Management. 70: 236–245. doi:10.2193/0022-541x(2006)70[236:esiatf]2.0.co;2.

- ^ Conroy, MJ; P Beier; H Quigley & MR Vaughan (2006). "Improving the use of science in conservation: lessons from the Florida panther" (PDF). Journal of Wildlife Management. 70: 1–7. doi:10.2193/0022-541X(2006)70[1:ITUOSI]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Information Quality Guidelines: Your Questions and Our Responses. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Published 2005-03-21. Retrieved 2007-01-30.

- ^ Kostyack, J and Hill, K. (2005) Giving Away the Store. The Florida Panther Society

- ^ Kostyack, J and Hill, K. (2004) Discrediting a Decade of Panther Science: Implications of the Scientific Review Team Report. The Florida Panther Society

- ^ Fish and Wildlife Service releases Draft Florida Panther Recovery Plan for public review. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Published 2006-01-31. Retrieved 2007-01-30.

External links[]

| Wikispecies has information related to Puma concolor coryi. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Puma concolor coryi. |

- Florida Panther Net – by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

- Florida Panther – National Park Service website

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Press Release on new Draft Recovery Plan

- The Florida Panther Society, Inc.

- Florida Panther Project

- Bounding, Rebounding: Panthers Make a Comeback – audio report by NPR (requires JavaScript, pop-ups, and Adobe Flash Player)

- Puma (genus)

- Mammals described in 1899

- Mammals of the United States

- Symbols of Florida

- Fauna of the Southeastern United States

- Controversial mammal taxa

- ESA endangered species

- Species endangered by habitat fragmentation