Footloose (1984 film)

| Footloose | |

|---|---|

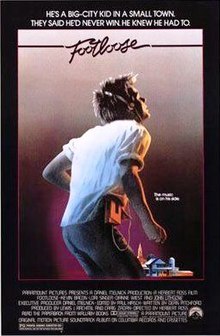

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Herbert Ross |

| Written by | Dean Pitchford |

| Produced by | |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Ric Waite |

| Edited by | Paul Hirsch |

| Music by | |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 110 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $8.2 million[2] |

| Box office | $80 million (domestic)[2] |

Footloose is a 1984 American musical drama film directed by Herbert Ross. It tells the story of Ren McCormack (Kevin Bacon), a teenager from Chicago who moves to a small town, where he attempts to overturn the ban on dancing instituted by the efforts of a local minister (John Lithgow).

Despite some critical reviews, the film did well at the box office and has gained a cult following over the years. It received praise for its music, with the songs “Footloose” by Kenny Loggins and “Let's Hear It for the Boy” by Deniece Williams being nominated for the Academy Award for Best Original Song.

Plot[]

Chicago native Ren McCormack and his mother Ethel move to the small town of Bomont to live with Ren's aunt and uncle in the rural Southwest. While attending church, Ren meets Reverend Shaw Moore, his wife Vi, and daughter Ariel. Ariel recklessly endangers her life by rebelling against Shaw's strict religious nature, much to the ire of her friends and boyfriend Chuck Cranston.

At school, Ren befriends Willard Hewitt, and learns the town council has banned dancing and rock music within the town boundary. He soon begins to fall for Ariel. After trading insults with Chuck, Ren is challenged to a game of chicken involving tractors. Ren wins when his shoelace becomes stuck and prevents him from jumping from the tractor. Shaw distrusts Ren, and forbids Ariel from seeing him after she shows an interest in him.

Wanting to show his friends the joy and freedom of dance, Ren drives Ariel, Willard, and her best friend Rusty to a country bar 100 miles away from Bomont. Once there, Willard is unable to dance and gets into a jealous fight with a man who dances with Rusty. On the drive home, the gang crosses a bridge where Ariel tells the story about how her older brother died in a car accident while driving under the influence of alcohol after a night of dancing. The accident destroyed Shaw, and prompted him to persuade the town council to enact strict anti-liquor, anti-drug, and anti-dance laws. Ariel begins to openly challenge Shaw's authority at home. Ren decides to challenge the anti-dancing ordinance so that the high school can hold a senior prom.

Willard is embarrassed at his inability to dance with Rusty, leading Ren to give him private lessons after school hours. Chuck confronts Ariel about her feelings towards Ren behind the bleachers. Provoked by his insults, Ariel throws the first punch, which Chuck retaliates to with a backhand slap, knocking her to the ground. Realizing what he's done, Chuck begins to remove himself from the situation and getting back into his vehicle; however, Ariel further escalates the situation by getting a pole and starting to smash the lights of Chuck's pickup, he grabs her to prevent further damage, but she continues to fight - it is only ended by Chuck finally astride her after a scuffle with one final slap, incapacitating her and allowing him to drive away, telling her that he "was through with her anyway". Ren helps Ariel clean herself up before going home, cementing their relationship. Later that night, a brick with the words "Burn in Hell" is thrown through the window of Ren's house, causing his uncle to lash out at his outspoken behavior. Ethel reveals that she was fired by her boss because of Ren's actions, but tells her son to stand up for what he believes is right.

With Ariel's help, Ren goes before the town council and reads several Bible verses to cite scriptural significance of dancing as a way to rejoice, exercise, and celebrate. Although Shaw is moved, the council votes against Ren's proposal, but Vi, who supports the movement, explains to Shaw that he cannot be everyone's father and that he is hardly being a father to Ariel.

Despite further discussion with Ren about his own family losses and Ariel's opening up about her own past, disclosing that she has had sexual relations, Shaw cannot bring himself to change his stance. The next day, Shaw sees members of his congregation burning library books that they claim are dangerous to the town's youth. Realizing the situation has gotten out of hand, Shaw stops the book-burning, rebukes the people, and sends them home.

The following Sunday, Shaw asks his congregation to pray for the high school students putting on the prom, which is set up at a grain mill just outside the Bomont town limits. On prom night, Shaw and Vi listen from outside the mill, dancing for the first time in years. Chuck and his friends arrive and attack Willard; Ren arrives in time to even the odds and knocks out Chuck. Ren, Ariel, Willard, and Rusty rejoin the party and happily dance the night away.

Cast[]

- Kevin Bacon as Ren McCormack

- Lori Singer as Ariel Moore

- Dianne Wiest as Vi Moore

- John Lithgow as Rev. Shaw Moore

- Chris Penn as Willard Hewitt

- Sarah Jessica Parker as Rusty

- John Laughlin as Woody

- Elizabeth Gorcey as Wendy Jo

- Frances Lee McCain as Ethel McCormack

- Jim Youngs as Chuck Cranston

- Timothy Scott as Andy Beamis

- Andrea Hays as Bar Patron

- Arthur Rosenberg as Wes Warnicker

Production[]

Dean Pitchford, an Academy Award-winning lyricist for the title song for the 1980 film Fame, came up with the idea for Footloose in 1979 and teamed up with Melnick's IndieProd who set the production up at 20th Century Fox in 1981.[3][4] Pitchford wrote the screenplay (his first) and most of the lyrics however, Fox put it into turnaround.[4] In 1982, Paramount Pictures made a pay-or-play deal for the film.[4] When negotiations with Herbert Ross initially stalled, Ron Howard was approached to direct the film but he turned it down to direct Splash instead.[5] Michael Cimino was hired by Paramount to direct the film, his first film since Heaven's Gate.[4]

After a month working on the film, the studio fired Cimino, who was making extravagant demands for the production, including demanding an additional $250,000 for his work, and ended up hiring Ross.[4][6]

Casting[]

Tom Cruise and Rob Lowe were both slated to play the lead. The casting directors were impressed with Cruise because of the famous underwear dance sequence in Risky Business, but he was unavailable for the part because he was filming All the Right Moves. Lowe auditioned three times and had dancing ability and the "neutral teen" look that the director wanted, but injury prevented him from taking the part.[7] Christopher Atkins claims that he was cast as Ren but lost the role.[8] Bacon had been offered the main role for the Stephen King film Christine at the same time that he was asked to do the screen test for Footloose. He chose to take the gamble on the screen test. After watching his earlier film Diner, the director persuaded the producers to go with Bacon.

The film also stars Lori Singer as Reverend Moore's independent daughter Ariel, a role for which Madonna also auditioned. Daryl Hannah turned down the offer to play Ariel in order to play Madison in Splash. Elizabeth McGovern turned down the role to play Deborah Gelly in Once Upon a Time in America. Melanie Griffith, Michelle Pfeiffer, Jamie Lee Curtis, Rosanna Arquette, Meg Tilly, Julia Louis-Dreyfus, Heather Locklear, Meg Ryan, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Jodie Foster, Phoebe Cates, Tatum O'Neal, Bridget Fonda, Lori Loughlin, Diane Lane and Brooke Shields were all considered for the role of Ariel. Dianne Wiest appears as Vi, the Reverend's devoted yet conflicted wife.

Tracy Nelson was considered for the role of Rusty.[9]

The film features an early film appearance by Sarah Jessica Parker as Ariel's friend Rusty, for which she received a Best Young Supporting Actress in a Motion Picture Musical, Comedy, Adventure or Drama nomination at the Sixth Annual Youth in Film Awards. It was also an early role for Chris Penn as Willard Hewitt, who is taught how to dance by his friend Ren.

Filming[]

The film was shot at various locations in Utah County, Utah. The high school and tractor scenes were filmed in and around Payson and Payson High School. The church scenes were filmed in American Fork and the steel mill was the Geneva Steel mill in Vineyard. The drive-in scenes were filmed in Provo at what was then the "High Spot" restaurant. The restaurant closed in the late 1980s and there is now an auto parts store located at 200 N 500 W. The final sequence was filmed in Lehi with the Lehi Roller Mills featured in the final sequence.

For his dance scene in the warehouse, Bacon said he had four stunt doubles: "I had a stunt double, a dance double [Peter Tramm][10] and two gymnastics doubles."[11] Principal photography took place from May 9, 1983 to January 1984.

Film inspiration[]

Footloose is loosely based on the town of Elmore City, Oklahoma. The town had banned dancing since its founding in 1898 in an attempt to decrease the amount of heavy drinking. One advocate of the dancing ban was the Reverend from the nearby town of Hennepin, F.R. Johnson. He said, "No good has ever come from a dance. If you have a dance somebody will crash it and they'll be looking for only two things - women and booze. When boys and girls hold each other, they get sexually aroused. You can believe what you want, but one things leads to another." Because of the ban on dancing, the town never held a prom. In February 1980, the junior class of Elmore City's high school made national news when they requested permission to hold a junior prom and it was granted. The request to overturn the ban in order to hold the prom was met with a 2-2 decision from the school board when school board president Raymond Lee broke the tie with the words, "Let 'em dance."[12]

In 1981, Lynden, a small town in Washington State, passed an ordinance that banned the practice of dancing at events and locations where alcohol would be served. This incident received national attention. And since this event happened only years before Footloose was released, the local residents believe that these two things are not a coincidence.[13][14]

Soundtrack[]

The soundtrack was released in cassette, 8-track tape, vinyl, and CD format. The soundtrack was also re-released on CD for the 15th anniversary of the film in 1999. The re-release included four new songs: "Bang Your Head (Metal Health)" by Quiet Riot, "Hurts So Good" by John Mellencamp, "Waiting for a Girl Like You" by Foreigner, and the extended 12" remix of "Dancing in the Sheets".

The album includes "Footloose" and "I'm Free", both by Kenny Loggins, "Holding Out for a Hero" by Bonnie Tyler, "Girl Gets Around" by Sammy Hagar, "Never" by Australian rock band Moving Pictures, "Let's Hear It for the Boy" by Deniece Williams, "Somebody's Eyes" by Karla Bonoff, and "Dancing In The Sheets" by Shalamar, and the romantic theme, "Almost Paradise" by Mike Reno from Loverboy and Ann Wilson of Heart. Some of the songs were composed by Eric Carmen and Jim Steinman and the soundtrack went on to sell over 9 million copies in the USA.

The first two tracks both hit No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 and received 1985 Academy Award nominations for Best Music (Original Song). "Footloose" also received a 1985 Golden Globe Award nomination for Best Original Song – Motion Picture.

The late film composer Miles Goodman has been credited for adapting and orchestrating the film's score.[15][16][17][18][19][20]

They released the music from the soundtrack before the movie was released. That way the music served as advertising for the movie. The filmmakers also felt that songs produced a stronger emotional response if you were already familiar with them, which heightened the experience of watching the movie. The music video for the song Footloose had scenes from the movie, rather than video of the singer.[21]

Reception[]

Critical response[]

The film received mixed reviews from critics. Chicago Sun-Times critic Roger Ebert called it "a seriously confused movie that tries to do three things, and does all of them badly. It wants to tell the story of a conflict in a town, it wants to introduce some flashy teenage characters, and part of the time it wants to be a music video."[22] Dave Denby in New York rechristened the film "Schlockdance", writing: "Footloose may be a hit, but it's trash - high powered fodder for the teen market... The only person to come out of the film better off is the smooth-cheeked, pug-nosed Bacon, who gives a cocky but likeable Mr. Cool performance."[23]

Jane Lamacraft reassessed the film for Sight and Sound's "Forgotten pleasures of the multiplex" feature in 2010, writing "Nearly three decades on, Bacon's vest-clad set-piece dance in a flour mill looks cheesily 1980s, but the rest of Ross's drama wears its age well, real song-and-dance joy for the pre-Glee generation."[24]

On Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 52% based on 42 reviews, with an average rating of 5.77/10. The consensus reads, "There's not much dancing, but what's there is great. The rest of the time, Footloose is a nice hunk of trashy teenage cheese."[25] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 42 out of 100 based on 12 critics, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[26]

Box office[]

The film grossed $80,035,403 domestically. It became the seventh highest-grossing film of 1984.[2]

Accolades[]

- Academy Award for Best Original Song: "Footloose" - Music and Lyrics by Kenny Loggins and Dean Pitchford (nominated)

- Academy Award for Best Original Song: "Let's Hear It for the Boy" - Music and Lyrics by Dean Pitchford and Tom Snow (nominated)

Musical adaptation[]

In 1998, a musical version of Footloose premiered.[28] Featuring many of the songs from the film, the show has been presented on London's West End, on Broadway, and elsewhere. The musical is generally faithful to the film version, with some slight differences in the story and characters.

Remake[]

Paramount announced plans to fast-track a musical remake of Footloose. The remake was written and directed by Craig Brewer. Filming started in September 2010. It was budgeted at $25 million.[29] It was released October 14, 2011.

References[]

- ^ "FOOTLOOSE (PG) (!)". British Board of Film Classification. February 20, 1984. Archived from the original on July 26, 2015. Retrieved July 8, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Footloose (1984) - Financial Information". The Numbers. Archived from the original on 2021-05-03. Retrieved 2019-09-07.

- ^ Ginsberg, Steven. "Cimino and Melnick Working Together on 'Footloose'". Daily Variety. p. 1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Footloose at the American Film Institute Catalog

- ^ https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/76738/15-surprising-facts-about-splash

- ^ Holleran, Scott (12 October 2004). "Shall We Footloose?". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 15 April 2009. Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- ^ Wenn (16 January 2013). "Rob Lowe: 'I refused to sing Footloose karaoke duet with Loggins". Hollywood.com. Archived from the original on 11 March 2014. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

Years ago I auditioned for Footloose and I blew out my ACL (anterior cruciate ligament), so I have post-traumatic stress with anything having to do with Footloose.

- ^ http://www.upi.com/Entertainment_News/2009/01/26/Atkins-I-almost-starred-in-Footloose/62571233008228/

- ^ https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/73151/18-catchy-facts-about-footloose

- ^ "Hoofers Hidden in the Shadows Dream of the Limelight". People. Time Inc. 2 April 1984. Archived from the original on 10 March 2011. Retrieved 15 December 2011.

- ^ Jones, Oliver (14 October 2011). "Kevin Bacon 'Furious' over Having a Dance Double in Footloose". People. Time Inc. Archived from the original on 16 October 2011. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- ^ "Dance Fever: The Town That Inspired (and Got) Footloose - 405 Magazine - June 2015 - Oklahoma City". www.405magazine.com. Archived from the original on 2019-05-02. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2020-06-05. Retrieved 2020-07-06.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2020-07-06. Retrieved 2020-07-06.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Miles Goodman, 47, Composer for Films". The New York Times. 20 August 1996. Archived from the original on 21 February 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ Jablon, Robert (18 August 1996). "MILES GOODMAN, FILM COMPOSER AND JAZZ RECORD PRODUCER, DIES". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 23 February 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ Oliver, Myrna (20 August 1996). "Miles Goodman; Record Producer, Film Composer". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 21 February 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ "Miles Goodman: Composer". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. 22 August 1996. Archived from the original on 3 May 2021. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ "Record producer, composer Miles Goodman dies at 47". The Daily Gazette. 21 August 1996. Archived from the original on 3 May 2021. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ "Miles Goodman, Composer For Films". Sun-Sentinel. 21 August 1996. Archived from the original on 23 February 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ The DVD commentary

- ^ Roger Ebert (January 1, 1984). "Footloose". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on May 3, 2021. Retrieved September 7, 2019.

- ^ Denby, David (February 27, 1984). "Schlockdance". New York. 17 (9). p. 60. Archived from the original on 3 May 2021. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- ^ Lamacraft, Jane. "forgotten-pleasures-of-the-multiplex". Sight & Sound. British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 8 November 2011. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- ^ "Footloose (1984)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Retrieved April 29, 2018.

- ^ "Footloose (1984) Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on October 13, 2018. Retrieved April 29, 2018.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs" (PDF). American Film Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-08-06. Retrieved 2016-08-14.

- ^ Willis, John (1 June 2002). Theatre World 1998-1999. Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-55783-432-4. Archived from the original on 21 March 2017. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- ^ John Beifuss. "'Footloose' runs off with well-heeled suitor: Georgia". MCA. Archived from the original on 2010-04-26. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

External links[]

| Look up footloose in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Footloose (1984 film) |

- Footloose at IMDb

- Footloose at Box Office Mojo

- Footloose at Rotten Tomatoes

- Footloose at The Numbers

- Footloose Review, history and filming locations

This movie premiered on TBS Superstation on April 5 at 6:00PM

- 1984 films

- English-language films

- 1984 romantic drama films

- 1980s coming-of-age drama films

- 1980s dance films

- 1980s high school films

- 1980s musical drama films

- 1980s romantic musical films

- 1980s teen drama films

- 1980s teen romance films

- American coming-of-age drama films

- American dance films

- American films

- American high school films

- American musical drama films

- American romantic drama films

- American romantic musical films

- American teen drama films

- American teen musical films

- American teen romance films

- Coming-of-age romance films

- Films about proms

- Films adapted into plays

- Films directed by Herbert Ross

- Films set in Oklahoma

- Films shot in Utah

- Paramount Pictures films