Forensic palynology

| Part of a series on |

| Forensic science |

|---|

|

|

Forensic palynology is a subdiscipline of palynology (the study of pollen grains, spores, etc.), that aims to prove or disprove a relationship among objects, people, and places that may pertain to both criminal and civil cases. Pollen can reveal where a person or object has been, because regions of the world, countries, and even different parts of a single garden will have a distinctive pollen assemblage.[1] Pollen evidence can also reveal the season in which a particular object picked up the pollen.[2]

Palynology is the study of palynomorphs - microscopic structures of both animal and plant origin that are resistant to decay. This includes spermatophyte pollen, as well as spores (fungi, bryophytes, and ferns), dinoflagellates, and various other organic microorganisms - both living and fossilized.[3] There are a variety of ways in which the study of these microscopic, walled particles can be applied to criminal forensics.

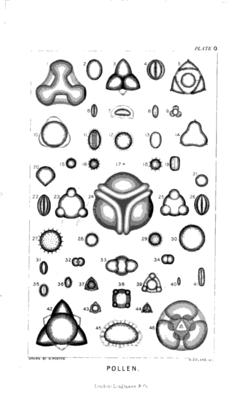

Pollen and similar spores are generally less than 50 microns across. Pollen is very easily transported unnoticed, and a very small sample can yield thousands of pollen grains.[4] Pollen grains have a variety of shapes and forms, and numbers identification keys exist as a reference. Large-scale collections of pollen specimens that reside in museums and university herbaria also serve as a resource for forensic palynologists. Pollen can be classified by size, shape, color, and by features of their apertures and ornamentation.

A sample of pollen from a crime scene can help to identify a specific plant species that may have had contact with a victim, or point to evidence that does not ecologically belong in the area. A pollen assemblage is a sample of pollen with a variety of plant species represented. Identifying those species and their relative frequency can point to a specific area or time of year. Pollen is made in great numbers, by a large variety of plants, and it is designed to be dispersed (either via wind, insect, or another method) throughout the immediate environment. Pollen can also be found in soil/rock samples.[5]

Pollen has been used to trace activity at mass graves in Bosnia,[6] pinpoint the scene of a crime,[5] and catch a burglar who brushed against a Hypericum bush during a crime.[7] Because pollen has distinct morphology, is likely to adhere to a variety of surfaces, and is relatively indestructible, it has even become a part of ongoing research into forensic bullet coatings.[8]

Examples[]

Austria, 1959[]

One of the earliest document cases in which pollen plays a key role took place in Austria. A man went missing, and was presumed murdered, but no body was found. The authorities had arrested a suspect, who had motive for the murder, but did not have a body or confession, and the case stalled. A search of the suspect's belongings yielded a pair of muddy boots. The mud was sampled and given to Wilhelm Klaus, at the University of Vienna's Paleobotany Department, for analysis. Dr. Klaus found modern pollen from a variety of species, including spruce, willow, and alder. He also found fossilized hickory pollen grains, from a species long extinct. There was only one area of the Danube River Valley that hosted those living plants, and had Miocene-aged rock deposits that would contain the fossilized species. When the suspect was presented with this information, he willingly confessed and lead authorities to the sites of both the murder and the body, both of which were inside the region indicated by Dr. Klaus.[5][9]

New Zealand, 2005[]

After a home invasion, two burglars brushed past a Hypericum bush outside of the house. One of the burglars was brought in as a suspect, but all evidence was circumstantial, and the man did not confess. Analysis of his clothes revealed the Hypericum pollen. The presence of pollen is ubiquitous, but in this case, the pollen was clumped onto the clothing (rather than dusted) and did not seem to be simply the result of air dispersal. It was ultimately concluded that "the clothes had so much Hypericum pollen on them that they had to have been in direct and intimate contact with a flowering bush."[7]

References[]

- ^ Vaughn M. Bryant. "Forensic Palynology: A New Way to Catch Crooks". Archived from the original on 3 February 2007.

- ^ Robert Stackhouse (17 April 2003), "Forensics studies look to pollen", The Battalion, archived from the original on 23 April 2013

- ^ Alotaibi, Saqer S.; Sayed, Samy M.; Alosaimi, Manal; Alharthi, Raghad; Banjar, Aseel; Abdulqader, Nosaiba; Alhamed, Reem (1 May 2020). "Pollen molecular biology: Applications in the forensic palynology and future prospects: A review". Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences. 27 (5): 1185–1190. doi:10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.02.019. ISSN 1319-562X. PMC 7182995. PMID 32346322.

- ^ "NaturePlus: Curator of Micropalaeontology's blog: A modern pollen and spore collection - useful to Palaeontologists?". www.nhm.ac.uk. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- ^ a b c Mildenhall, Dallas (2008). "Civil and criminal investigations. The use of spores and pollen". SIAK-Journal − Zeitschrift für Polizeiwissenschaft und polizeiliche Praxis (4): 35–52. doi:10.7396/2008_4_E.

- ^ Peter Wood (9 September 2004), "Pollen helps war crime forensics", BBC News, retrieved 4 January 2010

- ^ a b D. Mildenhall (2006), "Hypericum pollen determines the presence of burglars at the scene of a crime: An example of forensic palynology", Forensic Science International, 163 (3): 231–235, doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2005.11.028, PMID 16406430

- ^ Sermon, Paul A.; Worsley, Myles P.; Cheng, Yu; Courtney, Lee; Shinar-Bush, Verity; Ruzimuradov, Olim; Hopwood, Andy J.; Edwards, Michael R.; Gashi, Bekim; Harrison, David; Xu, Yanmeng (September 2012). "Deterring gun crime materially using forensic coatings". Forensic Science International. 221 (1–3): 131–136. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2012.04.021.

- ^ "Forensic Palynology: A New Way to Catch Crooks" Check

|url=value (help). http. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- Forensic palynology

- Palynology

- Forensic disciplines