Frederick William IV of Prussia

| Frederick William IV | |

|---|---|

Frederick William IV in 1847 | |

| King of Prussia | |

| Reign | 7 June 1840 – 2 January 1861 |

| Predecessor | Frederick William III |

| Successor | William I |

| Regent | Prince William (1858–1861) |

| President of the Erfurt Union | |

| In office | 26 May 1849 – 29 November 1850 |

| Born | 15 October 1795 Kronprinzenpalais, Berlin, Kingdom of Prussia |

| Died | 2 January 1861 (aged 65) Sanssouci, Potsdam, Kingdom of Prussia |

| Burial | Crypt of the Friedenskirche, Sanssouci Park, Potsdam[1]

(Heart in the Mausoleum at Charlottenburg Palace, Berlin)[2] |

| Spouse | Elisabeth Ludovika of Bavaria |

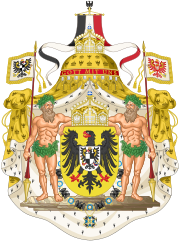

| House | Hohenzollern |

| Father | Frederick William III of Prussia |

| Mother | Louise of Mecklenburg-Strelitz |

| Religion | Lutheranism (Prussian United) |

| Signature | |

| Prussian Royalty |

| House of Hohenzollern |

|---|

|

| Frederick William III |

|

| Frederick William IV |

Frederick William IV (German: Friedrich Wilhelm IV.; 15 October 1795[3] – 2 January 1861), the eldest son and successor of Frederick William III of Prussia, reigned as King of Prussia from 7 June 1840 to his death on 2 January 1861. Also referred to as the "romanticist on the throne", he is best remembered for the many buildings he had constructed in Berlin and Potsdam as well as for the completion of the Gothic Cologne Cathedral.

In politics, he was a conservative, who initially pursued a moderate policy of easing press censorship and reconciling with the Catholic population of the kingdom. During the German revolutions of 1848–1849, he at first accommodated the revolutionaries but rejected the title of Emperor of the Germans offered by the Frankfurt Parliament in 1849, believing that Parliament did not have the right to make such an offer. He used military force to crush the revolutionaries throughout the German Confederation. From 1849 onward he converted Prussia into a constitutional monarchy and acquired the port of Wilhelmshaven in the Jade Treaty of 1853.[4]

From 1857 to 1861, he suffered several strokes and was left incapacitated until his death. His brother (and heir-presumptive) Wilhelm served as regent after 1858 and then succeeded him as King.

Early life[]

Born to Frederick William III by his wife Queen Louise, he was her favourite son.[3] Frederick William was educated by private tutors, many of whom were experienced civil servants, such as Friedrich Ancillon.[3] He also gained military experience by serving in the Prussian Army during the War of Liberation against Napoleon in 1814, although he was an indifferent soldier. He was a draftsman interested in both architecture and landscape gardening and was a patron of several great German artists, including architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel and composer Felix Mendelssohn. In 1823 he married Elisabeth Ludovika of Bavaria. Since she was a Roman Catholic, the preparations for this marriage included difficult negotiations which ended with her conversion to Lutheranism. There were two wedding ceremonies—one in Munich, and another in Berlin. The couple had a very harmonious marriage, but, after a single miscarriage in 1828,[5] it remained childless.[6]

Frederick William was a staunch Romanticist, and his devotion to this movement, which in the German States featured nostalgia for the Middle Ages, was largely responsible for his developing into a conservative at an early age. In 1815, when he was only twenty, the crown prince exerted his influence to structure the proposed new constitution of 1815, which was never actually enacted, in such a way that the landed aristocracy would hold the greatest power. He was firmly against the liberalization of Germany and only aspired to unify its many states within what he viewed as a historically legitimate framework, inspired by the ancient laws and customs of the recently dissolved Holy Roman Empire. Frederick William opposed the idea of a unified German state, believing that Austria was divinely ordained to rule over Germany,[citation needed] and contented himself with the title of "Grand General of the Realm".

Reign[]

Early reign[]

Frederick William became King of Prussia on the death of his father in 1840. Through a personal union, he also became the sovereign prince of the Principality of Neuchâtel (1840–1857), today part of Switzerland. In 1842, he gave his father's menagerie at Pfaueninsel to the new Berlin Zoo, which opened its gates in 1844 as the first of its kind in Germany. Other projects during his reign—often involving his close collaboration with the architects—included the Alte Nationalgalerie (Old National Gallery) and the Neues Museum in Berlin, the Orangerieschloss at Potsdam as well as the reconstruction of Schloss Stolzenfels on the Rhine (Prussian since 1815) and Burg Hohenzollern, in the ancestral homelands of the dynasty which became part of Prussia in 1850.[6] He also enlarged and redecorated his father's Erdmannsdorf manor house.

Although a staunch conservative, Frederick William did not seek to be a despot, and so he toned down the reactionary policies pursued by his father, easing press censorship and promising to enact a constitution at some point, but he refused to create an elected legislative assembly, preferring to work with the nobility through "united committees" of the provincial estates. When he finally called a national assembly in 1847, it was not a representative body, but rather a United Diet comprising all the provincial estates, which had the right to levy taxes and take out loans, but no right to meet at regular intervals.

Despite being a devout Lutheran, his Romantic leanings led him to settle the Cologne church conflict by releasing the imprisoned Clemens August von Droste-Vischering, the Archbishop of Cologne. He also patronized further construction of Cologne Cathedral, Cologne having become part of Prussia in 1815. In 1844, he attended the celebrations marking the completion of the cathedral, becoming the first King of Prussia to enter a Roman Catholic house of worship.

In 1842, on advice of Alexander von Humboldt, he founded the separate civil class of the Pour le Merite, the Order Pour le Mérite for Sciences and Arts (Orden Pour le Mérite für Wissenschaften und Künste). Said civil order is still being awarded today.

Revolutions of 1848[]

When revolution broke out in Prussia in March 1848, part of the larger series of Revolutions of 1848, the king initially moved to repress it with the army, but on 19 March he decided to recall the troops and place himself at the head of the movement. He committed himself to German unification, formed a liberal government, convened a national assembly, and ordered that a constitution be drawn up. Once his position was more secure again, however, he quickly had the army reoccupy Berlin and in December dissolved the assembly.

He did, however, remain dedicated to unification for a time, leading the Frankfurt Parliament to offer him the crown of Germany on 3 April 1849, which he refused, purportedly saying that he would not accept a "crown from the gutter" (German: "Krone aus der Gosse"). The King's refusal was rooted in his Romantic aspiration to re-establish the medieval Holy Roman Empire, comprising smaller, semi-sovereign monarchies under the limited authority of a Habsburg emperor. Therefore, Frederick William would only accept the imperial crown after being elected by the German princes, as per the former empire's ancient customs.[7] He expressed this sentiment in a letter to his sister the Empress Alexandra Feodorovna of Russia, in which he said the Frankfurt Parliament had overlooked that "in order to give, you would first of all have to be in possession of something that can be given."[8] In the king's eyes, only a reconstituted College of Electors could possess such authority.[9]

With the failed attempt by the Frankfurt Parliament to include the Habsburgs in a newly unified German Empire, the Parliament turned to Prussia. Seeing Austrian ambivalence towards Prussia taking a more powerful role in German affairs, Frederick William began considering a Prussian-led union. All German states, excluding those of the Habsburgs, would be unified under Hohenzollern authority, and these two polities would be linked in an overarching political framework.[10] Frederick William, therefore, did attempt to establish the Erfurt Union, a union of the German states except for Austria, but abandoned the idea by the Punctation of Olmütz on 29 November 1850, in the face of renewed Austrian and Russian resistance. The German Confederation remained the common government of German Europe.

| Silver Coin of Frederick William IV, struck 1860 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Obverse (German): FRIEDR[ICH] WILHELM IV KOENIG V[ON] PREUSSEN, or in English, "Frederick William IV, King of Prussia" | Reverse (German): EIN VEREINSTHALER XXX EIN PFUND FEIN 1860, or in English, "One Double Thaler 30 to the Fine Pound" |

Later years and death[]

Rather than returning to bureaucratic rule after dismissing the Prussian National Assembly, Frederick William promulgated a new constitution that created a Parliament of Prussia with two chambers, an aristocratic upper house and an elected lower house. The lower house was elected by all taxpayers, but in a three-tiered system based on the amount of taxes paid, so that true universal suffrage was denied. The constitution also reserved to the king the power of appointing all ministers, re-established the conservative district assemblies and provincial diets, and guaranteed that the civil service and the military remained firmly under control of the king. This was a more liberal system than had existed in Prussia before 1848, but it was still a conservative system of government in which the monarch, the aristocracy, and the military retained most of the power. This constitution remained in effect until the dissolution of the Prussian kingdom in 1918.

Following the revolutions of 1848, the increasingly gloomy king withdrew from the public eye, surrounding himself with advisers who preached absolute orthodoxy and conservatism in religious and political matters. A series of strokes from 14 July 1857 onward left the king partially paralyzed and largely mentally incapacitated, and his brother (and heir-presumptive) William served as regent after 7 October 1858. On 24 November 1859, the king suffered a stroke that left him paralyzed on the left side. He was driven around in a wheelchair from then on. On 4 November 1860, he lost consciousness after another stroke. One more stroke resulted in the king's death at Sanssouci palace on 2 January 1861, at which point the regent acceded to the throne as William I of Prussia.

In accordance with his testamentary instructions from 1854, Frederick William IV is interred with his wife in the crypt underneath the Church of Peace in the park of Sanssouci, at Potsdam, while his heart was removed from his body and buried alongside his parents at the Charlottenburg Palace mausoleum.[6]

Religion[]

He was a Lutheran member of the Evangelical State Church of Prussia, a United Protestant denomination that brought together Reformed and Lutheran believers.

Honours[]

- German decorations[11]

Prussia:

Prussia:

- Knight of the Black Eagle, 15 October 1805[12]

- Iron Cross, 2nd Class

- Service Award Cross

Ascanian duchies: Grand Cross of Albert the Bear, 18 May 1838[13]

Ascanian duchies: Grand Cross of Albert the Bear, 18 May 1838[13] Baden:[14]

Baden:[14]

Bavaria: Knight of St. Hubert, 1823[15]

Bavaria: Knight of St. Hubert, 1823[15] Brunswick: Grand Cross of Henry the Lion[16]

Brunswick: Grand Cross of Henry the Lion[16]

Ernestine duchies: Grand Cross of the Saxe-Ernestine House Order, October 1838[17]

Ernestine duchies: Grand Cross of the Saxe-Ernestine House Order, October 1838[17] Hanover:

Hanover:

Hesse and by Rhine: Grand Cross of the Ludwig Order, 11 April 1830[20]

Hesse and by Rhine: Grand Cross of the Ludwig Order, 11 April 1830[20] Hesse-Kassel: Grand Cross of the Golden Lion, 5 September 1841[21]

Hesse-Kassel: Grand Cross of the Golden Lion, 5 September 1841[21] Hohenzollern: Cross of Honour of the Princely House Order of Hohenzollern, 1st Class[22]

Hohenzollern: Cross of Honour of the Princely House Order of Hohenzollern, 1st Class[22] Nassau: Knight of the Gold Lion of Nassau, May 1858[23]

Nassau: Knight of the Gold Lion of Nassau, May 1858[23] Oldenburg: Grand Cross of the Order of Duke Peter Friedrich Ludwig, with Golden Crown, 8 October 1843[24]

Oldenburg: Grand Cross of the Order of Duke Peter Friedrich Ludwig, with Golden Crown, 8 October 1843[24] Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach: Grand Cross of the White Falcon, 16 February 1829[25]

Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach: Grand Cross of the White Falcon, 16 February 1829[25] Saxony: Knight of the Rue Crown, 1839[26]

Saxony: Knight of the Rue Crown, 1839[26] Württemberg: Grand Cross of the Civil Merit Order, 1818[27]

Württemberg: Grand Cross of the Civil Merit Order, 1818[27]

- Foreign decorations[11]

Austrian Empire: Grand Cross of St. Stephen, 1833[28]

Austrian Empire: Grand Cross of St. Stephen, 1833[28] Belgium: Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold, 18 January 1850[29]

Belgium: Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold, 18 January 1850[29] Denmark: Knight of the Elephant, 19 January 1840[30]

Denmark: Knight of the Elephant, 19 January 1840[30]- France:

Kingdom of France:[31]

Kingdom of France:[31]

- Knight of the Holy Spirit, 5 February 1824

- Knight of St. Michael, 5 February 1824

French Empire: Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour, November 1856[32]

French Empire: Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour, November 1856[32]

Kingdom of Greece: Grand Cross of the Redeemer

Kingdom of Greece: Grand Cross of the Redeemer Netherlands:

Netherlands:

- Grand Cross of the Military William Order, 9 February 1842[33]

- Grand Cross of the Netherlands Lion

Duchy of Parma: Senator Grand Cross of the Constantinian Order of St. George, with Collar, 1856[34]

Duchy of Parma: Senator Grand Cross of the Constantinian Order of St. George, with Collar, 1856[34] Russian Empire:

Russian Empire:

- Knight of St. Andrew, 15 September 1801

- Knight of St. George, 4th Class

Kingdom of Poland: Knight of the White Eagle, 1829[35]

Kingdom of Poland: Knight of the White Eagle, 1829[35] Kingdom of Sardinia: Knight of the Annunciation, 9 October 1847[36]

Kingdom of Sardinia: Knight of the Annunciation, 9 October 1847[36] Spain: Knight of the Golden Fleece, 10 February 1818[37]

Spain: Knight of the Golden Fleece, 10 February 1818[37] Sweden: Knight of the Seraphim, 29 August 1811[38]

Sweden: Knight of the Seraphim, 29 August 1811[38] Two Sicilies:

Two Sicilies:

United Kingdom: Knight of the Garter, 25 January 1842[39]

United Kingdom: Knight of the Garter, 25 January 1842[39]

Ancestry[]

See also[]

Notes[]

- ^ Dorgerloh, Hartmut, ed. (18 August 2011). "Palaces and Gardens in Potsdam: 18-Church of Peace" (PDF). Palaces and Gardens. Prussian Palaces and Gardens Foundation Berlin-Brandenburg. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2010. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

The Church of Peace was built from 1845– 54, based upon Italian models. King Frederick William IV and Queen Elisabeth were laid to rest here.

CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link) - ^ Stiftung Preußische Schlösser und Gärten Berlin-Brandenburg, (Hartmut Dorgerloh, ed) (1992–2012). "König Friedrich Wilhelm IV". Potsdam, Brandenburg, Germany: Ministerium für Wissenschaft, Forschung und Kultur des Landes Brandenburg. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

Begräbnisstätte: Friedenskirche im Park von Sanssouci; das Herz im Mausoleum im Park von Schloss Charlottenburg in Berlin

[permanent dead link] - ^ a b c Koch 2014, p. 227.

- ^ David Barclay, Frederick William IV and the Prussian Monarchy 1840–1862 (Oxford, 1995).

- ^ Letzner, Wolfram (2016). Berlin – eine Biografie. Menschen und Schicksale von den Askaniern bis Helmut Kohl und zur Hauptstadt Deutschlands (German). Nünnerich Asmus, Mainz. ISBN 978-3-945751-37-4.

- ^ a b c Feldhahn, Ulrich (2011). Die preußischen Könige und Kaiser (German). Kunstverlag Josef Fink, Lindenberg. pp. 21–23. ISBN 978-3-89870-615-5.

- ^ Clark, Christopher (2006). Iron Kingdom: The Rise and Downfall of Prussia, 1600–1947. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. pp. 490.

- ^ Ibid. p. 494.

- ^ Ibid. p. 490.

- ^ Ibid. 495.CS1 maint: location (link)

- ^ a b "Königliches Haus", Hof- und Staats-Handbuch des Königreichs Preußen (in German), Berlin, 1839, p. 3, retrieved 11 March 2020

- ^ Liste der Ritter des Königlich Preußischen Hohen Ordens vom Schwarzen Adler (1851), "Von Seiner Majestät dem Könige Friedrich Wilhelm III. ernannte Ritter" p. 15

- ^ Anhalt-Köthen (1851). Staats- und Adreß-Handbuch für die Herzogthümer Anhalt-Dessau und Anhalt-Köthen: 1851. Katz. p. 10.

- ^ Hof- und Staats-Handbuch des Großherzogtum Baden (1838), "Großherzogliche Orden" pp. 28, 42

- ^ Bayern (1858). Hof- und Staatshandbuch des Königreichs Bayern: 1858. Landesamt. p. 7.

- ^ Braunschweigisches Adreßbuch für das Jahr 1858. Braunschweig 1858. Meyer. p. 5

- ^ "Herzogliche Sachsen-Ernestinischer Hausorden", Adreß-Handbuch des Herzogthums Sachsen-Coburg und Gotha (in German), Coburg, Gotha: Meusel, 1843, p. 6, retrieved 12 March 2020

- ^ Hof- und Staatshandbuch für das Königreich Hannover: 1837. Berenberg. 1837. p. 20.

- ^ Staat Hannover (1857). Hof- und Staatshandbuch für das Königreich Hannover: 1857. Berenberg. p. 32.

- ^ "Großherzogliche Orden und Ehrenzeichen", Hof- und Staatshandbuch des Großherzogtums Hessen: für das Jahr ... 1858 (in German), Darmstadt, 1858, p. 8, retrieved 12 March 2020

- ^ Hessen-Kassel (1858). Kurfürstlich Hessisches Hof- und Staatshandbuch: 1858. Waisenhaus. p. 15.

- ^ Hof- und Adreß-Handbuch des Fürstenthums Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen: 1844. Beck und Fränkel. 1844. p. 19.

- ^ Staats- und Adreß-Handbuch des Herzogthums Nassau: 1860. Schellenberg. 1860. p. 7.

- ^ Staat Oldenburg (1858). Hof- und Staatshandbuch des Großherzogtums Oldenburg: für ... 1858. Schulze. p. 30.

- ^ "Großherzoglicher Hausorden", Staatshandbuch für das Großherzogtum Sachsen / Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach (in German), Weimar: Böhlau, 1855, p. 10, retrieved 11 March 2020

- ^ Sachsen (1860). Staatshandbuch für den Freistaat Sachsen: 1860. Heinrich. p. 4.

- ^ Württemberg (1858). Königlich-Württembergisches Hof- und Staats-Handbuch: 1858. Guttenberg. p. 30.

- ^ "A Szent István Rend tagjai" Archived 22 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ H. Tarlier (1854). Almanach royal officiel, publié, exécution d'un arrête du roi (in French). 1. p. 37.

- ^ Kongelig Dansk Hof-og Statscalender Statshaandbog for det danske Monarchie for Aaret 1860, p.27 (in Danish). Retrieved 12 March 2020

- ^ Teulet, Alexandre (1863). "Liste chronologique des chevaliers de l'ordre du Saint-Esprit depuis son origine jusqu'à son extinction (1578–1830)" [Chronological List of Knights of the Order of the Holy Spirit from its origin to its extinction (1578–1830)]. Annuaire-bulletin de la Société de l'Histoire de France (in French) (2): 117. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- ^ M. & B. Wattel (2009). Les Grand'Croix de la Légion d'honneur de 1805 à nos jours. Titulaires français et étrangers. Paris: Archives & Culture. p. 509. ISBN 978-2-35077-135-9.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- ^ Militaire Willems-Orde: Preussen, Friederich Wilhelm IV von, (in Dutch)

- ^ Almanacco di corte. 1858. p. 221.

- ^ Kawalerowie i statuty Orderu Orła Białego 1705–2008 (2008), p. 289

- ^ Luigi Cibrario (1869). Notizia storica del nobilissimo ordine supremo della santissima Annunziata. Sunto degli statuti, catalogo dei cavalieri. Eredi Botta. p. 111.

- ^ "Caballeros existentes en la insignie Orden del Toison de Oro". Guía de forasteros en Madrid para el año de 1835 (in Spanish). En la Imprenta Nacional. 1835. p. 72.

- ^ Per Nordenvall (1998). "Kungl. Maj:ts Orden". Kungliga Serafimerorden: 1748–1998 (in Swedish). Stockholm. ISBN 91-630-6744-7.

- ^ Shaw, Wm. A. (1906) The Knights of England, I, London, p. 56

References[]

- Barclay, David E.,Frederick William IV and the Prussian Monarchy 1840–1862, (Oxford, 1995).

- Clark, Christopher. Iron Kingdom: The Rise and Downfall of Prussia, 1600–1947, by, (Harvard University Press, 2006).

- Koch, H.W. (2014). A History of Prussia. Routledge. ISBN 978-1317873082.

- Sheehan, James J. "Frederick William IV and the Prussian Monarchy: 1840-1861." English Historical Review 112.449 (1997): 1312–1314.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Friedrich Wilhelm IV. von Preußen. |

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- "Frederick William IV. of Prussia". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- "Frederick William IV.". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- 1795 births

- 1861 deaths

- 19th-century Kings of Prussia

- People from Berlin

- Kings of Prussia

- Princes of Neuchâtel

- Crown Princes of Prussia

- Prussian princes

- House of Hohenzollern

- People of the Revolutions of 1848

- Protestant monarchs

- Extra Knights Companion of the Garter

- German Calvinist and Reformed Christians

- Knights of the Golden Fleece of Spain

- Recipients of the Order of St. George of the Fourth Degree

- Honorary members of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences

- Burials at the Charlottenburg Palace Park Mausoleum, Berlin

- 19th-century German people

- 19th-century Protestants

- Knights Grand Cross of the Military Order of William

- Grand Crosses of the Order of Saint Stephen of Hungary

- Grand Croix of the Légion d'honneur

- Recipients of the Order of the Netherlands Lion

- Prussian Army personnel of the Napoleonic Wars

- German revolutions of 1848–1849