Legion of Honour

| National Order of the Legion of Honour Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur | |

|---|---|

| |

| Awarded by France | |

| Type | Order of merit |

| Established | 19 May 1802 |

| Motto | Honneur et patrie ("Honour and Fatherland") |

| Eligibility | Military and Civilians |

| Awarded for | Excellent civil or military conduct delivered, upon official investigation |

| Founder | Napoleon Bonaparte |

| Grand Master | President of France |

| Grand chancelier | Benoît Puga |

| Classes |

|

| Statistics | |

| First induction | 14 July 1804 |

| Precedence | |

| Next (higher) | None |

| Next (lower) |

|

Ribbon bars of the order | |

The Legion of Honour[a] is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleon Bonaparte, it has been retained (and slightly altered) by all later French governments and régimes.

The order's motto is Honneur et Patrie ("Honour and Fatherland"), and its seat is the Palais de la Légion d'Honneur next to the Musée d'Orsay, on the left bank of the Seine in Paris.[b]

The order is divided into five degrees of increasing distinction: Chevalier (Knight), Officier (Officer), Commandeur (Commander), Grand officier (Grand Officer), and Grand-croix (Grand Cross).

History[]

Consulat[]

During the French Revolution, all of the French orders of chivalry were abolished and replaced with Weapons of Honour. It was the wish of Napoleon Bonaparte, the First Consul, to create a reward to commend civilians and soldiers. From this wish was instituted a Légion d'honneur,[2] a body of men that was not an order of chivalry, for Napoleon believed that France wanted a recognition of merit rather than a new system of nobility. However, the Légion d'honneur did use the organization of the old French orders of chivalry, for example, the Ordre de Saint-Louis. The insignia of the Légion d'honneur bear a resemblance to those of the Ordre de Saint-Louis, which also used a red ribbon.

Napoleon originally created this award to ensure political loyalty. The organization would be used as a façade to give political favours, gifts, and concessions.[3] The Légion d'honneur was loosely patterned after a Roman legion, with legionaries, officers, commanders, regional "cohorts" and a grand council. The highest rank was not a Grand Cross but a Grand aigle (Grand Eagle), a rank that wore the insignia common to a Grand Cross. The members were paid, the highest of them extremely generously:

- 5,000 francs to a grand officier,

- 2,000 francs to a commandeur,

- 1,000 francs to an officier,

- 250 francs to a légionnaire.

Napoleon famously declared, "You call these baubles, well, it is with baubles that men are led... Do you think that you would be able to make men fight by reasoning? Never. That is good only for the scholar in his study. The soldier needs glory, distinctions, rewards."[4] This has been often quoted as "It is with such baubles that men are led."

The order was the first modern order of merit. Under the monarchy, such orders were often limited to Roman Catholics, and all knights had to be noblemen. The military decorations were the perks of the officers. The Légion d'honneur, however, was open to men of all ranks and professions—only merit or bravery counted. The new legionnaire had to be sworn into the Légion d'honneur. All previous orders were Christian, or shared a clear Christian background, whereas the Légion d'honneur is a secular institution. The badge of the Légion d'honneur has five arms.

First Empire[]

In a decree issued on the 10 Pluviôse XIII (30 January 1805), a grand decoration was instituted. This decoration, a cross on a large sash and a silver star with an eagle, symbol of the Napoleonic Empire, became known as the Grand aigle (Grand Eagle), and later in 1814 as the Grand cordon (big sash, literally "big ribbon"). After Napoleon crowned himself Emperor of the French in 1804 and established the Napoleonic nobility in 1808, award of the Légion d'honneur gave right to the title of "Knight of the Empire" (Chevalier de l'Empire). The title was made hereditary after three generations of grantees.

Napoleon had dispensed 15 golden collars of the Légion d'honneur among his family and his senior ministers. This collar was abolished in 1815.

Although research is made difficult by the loss of the archives, it is known that three women who fought with the army were decorated with the order: Virginie Ghesquière, Marie-Jeanne Schelling and a nun, Sister Anne Biget.[c]

The Légion d'honneur was prominent and visible in the French Empire. The Emperor always wore it, and the fashion of the time allowed for decorations to be worn most of the time. The king of Sweden therefore declined the order; it was too common in his eyes. Napoleon's own decorations were captured by the Prussians and were displayed in the Zeughaus (armoury) in Berlin until 1945. Today, they are in Moscow.

A depiction of Napoleon making some of the first awards of the Legion of Honour, at a camp near Boulogne on 16 August 1804.

As Emperor, Napoleon always wore the Cross and Grand Eagle of the Legion of Honour.

Embroidered insignia of the Legion of Honour, detail of Napoleon's uniform of colonel of the Chasseurs à cheval of the Imperial Guard

First Légion d'Honneur investiture, 15 July 1804, at Saint-Louis des Invalides by Jean-Baptiste Debret (1812).

Restoration of the Bourbon King of France in 1814[]

Louis XVIII changed the appearance of the order, but it was not abolished. To have done so would have angered the 35,000 to 38,000 members. The images of Napoleon and his eagle were removed and replaced by the image of King Henry IV, the popular first king of the Bourbon line. Three Bourbon fleurs-de-lys replaced the eagle on the reverse of the order. A king's crown replaced the imperial crown. In 1816, the grand cordons were renamed grand crosses and the legionnaires became knights. The king decreed that the commandants were now commanders. The Légion d'honneur became the second-ranking order of knighthood of the French monarchy, after the Order of the Holy Spirit.

July Monarchy[]

Following the overthrow of the Bourbons in favour of King Louis Philippe I of the House of Orléans, the Bourbon monarchy's orders were once again abolished and the Légion d'honneur was restored in 1830 as the paramount decoration of the French nation. The insignia were drastically altered; the cross now displayed tricolour flags. In 1847, there were 47,000 members.

Second Republic[]

Yet another revolution in Paris (in 1848) brought a new republic (the second) and a new design to the Légion d'honneur. A nephew of the founder, Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, was elected president and he restored the image of his uncle on the crosses of the order. In 1852, the first recorded woman, Angélique Duchemin, an old revolutionary of the 1789 uprising against the absolute monarchy, was admitted into the order. On 2 December 1851, President Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte staged a coup d'état with the help of the armed forces. He made himself Emperor of the French exactly one year later on 2 December 1852, after a successful plebiscite.

Second Empire[]

An Imperial crown was added. During Napoleon III's reign, the first American was admitted: Thomas Wiltberger Evans, dentist of Napoleon III.

Third Republic[]

In 1870, the defeat of the French Imperial Army in the Franco-Prussian War brought the end of the Empire and the creation of the Third Republic (1871–1940). As France changed, the Légion d'honneur changed as well. The crown was replaced by a laurel and oak wreath. In 1871, during the Paris Commune uprising, the Hôtel de Salm, headquarters of the Légion d'honneur, was burned to the ground in fierce street combats; the archives of the order were lost.

In the second term of President Jules Grévy, which started in 1885, newspaper journalists brought to light the trafficking of Grévy's son-in-law, Daniel Wilson, in the awarding of decorations of the Légion d'honneur. Grévy was not accused of personal participation in this scandal, but he was slow to accept his indirect political responsibility, which caused his eventual resignation on 2 December 1887.

During World War I, some 55,000 decorations were conferred, 20,000 of which went to foreigners. The large number of decorations resulted from the new posthumous awards authorised in 1918. Traditionally, membership in the Légion d'honneur could not be awarded posthumously.

Fourth and Fifth Republics[]

The establishment of the Fourth Republic in 1946 brought about the latest change in the design of the Legion of Honour. The date "1870" on the obverse was replaced by a single star. No changes were made after the establishment of the Fifth Republic in 1958.

Organization[]

Legal status and leadership[]

The Legion of Honour is a national order of France, meaning a public incorporated body. The Legion is regulated by a civil law code, the "Code of the Legion of Honour and of the Military Medal". While the President of the French Republic is the Grand Master of the order, day-to-day running is entrusted to the Grand Chancery (Grande Chancellerie de la Légion d'honneur).

Grand Master[]

Since the establishment of the Legion, the Grand Master of the order has always been the Emperor, King or President of France. President Emmanuel Macron therefore became the Grand Master of the Legion on 14 May 2017.[5]

The Grand Master appoints all other members of the order, on the advice of the French government. The Grand Master's insignia is the Grand Collar of the Legion. The President of the Republic, as Grand Master of the order, receives the Collar as part of his investiture, but the Grand Masters have not worn the Collar since Valéry Giscard d'Estaing.[6]

The Grand Chancery[]

The Grand Chancery is headed by the Grand Chancellor, usually a retired general, and the Secretary General, a civilian administrator.

- Grand Chancellor: General Benoît Puga (since 23 August 2016)

- Secretary-General: (since 2007)

The Grand Chancery also regulates the National Order of Merit and the médaille militaire (Military Medal). There are several structures funded by and operated under the authority of the Grand Chancery, like the Legion of Honour Schools (Maisons d'éducation de la Légion d'honneur) and the Legion of Honour Museum (Musée de la Légion d'honneur). The Legion of Honour Schools are élite boarding schools in Saint-Denis and Camp des Loges in the forest of Saint-Germain-en-Laye. Study there is restricted to daughters, granddaughters, and great-granddaughters of members of the order, the médaille militaire or the ordre national du Mérite.[7]

Membership[]

There are five classes in the Legion of Honour:

- Chevalier (Knight): minimum 20 years of public service or 25 years of professional activity with "eminent merits"

- Officier (Officer): minimum 8 years in the rank of Chevalier

- Commandeur (Commander): minimum 5 years in the rank of Officier

- Grand officier (Grand Officer): minimum 3 years in the rank of Commandeur

- Grand-croix (Grand Cross): minimum 3 years in the rank of Grand-officier

The "eminent merits" required to be awarded the order require the flawless performance of one's trade as well as doing more than ordinarily expected, such as being creative, zealous and contributing to the growth and well-being of others.

The order has a maximum quota of 75 Grand Cross, 250 Grand Officers, 1,250 Commanders, 10,000 Officers, and 113,425 (ordinary) Knights. As of 2010, the actual membership was 67 Grand Cross, 314 Grand Officers, 3,009 Commanders, 17,032 Officers and 74,384 Knights. Appointments of veterans of World War II, French military personnel involved in the North African Campaign and other foreign French military operations, as well as wounded soldiers, are made independently of the quota.

Members convicted of a felony (crime in French) are automatically dismissed from the order. Members convicted of a misdemeanour (délit in French) can be dismissed as well, although this is not automatic.

Wearing the decoration of the Légion d'honneur without having the right to do so is a serious offence. Wearing the ribbon or rosette of a foreign order is prohibited if that ribbon is mainly red, like the ribbon of the Legion of Honour. French military personnel in uniform must salute other military members in uniform wearing the medal, whatever the Légion d'honneur rank and the military rank of the bearer. This is not mandatory with the ribbon. In practice, however, this is rarely done.

There is not a single, complete list of all the members of the Legion in chronological order. The number is estimated at one million, including about 2,900 Knights Grand Cross.[8]

French nationals[]

French nationals, men and women, can be received into the Légion, for "eminent merit" (mérites éminents) in military or civil life. In practice, in current usage, the order is conferred to entrepreneurs, high-level civil servants, scientists, artists, including famous actors and actresses, sport champions,[d] and others with connections in the executive. Members of the French Parliament cannot receive the order, except for valour in war,[9] and ministers are not allowed to nominate their accountants.

Until 2008, French nationals could only enter the Legion of Honour at the class of Chevalier (Knight). To be promoted to a higher class, one had to perform new eminent services in the interest of France and a set number of years had to pass between appointment and promotion. This was however amended in 2008 when entry became possible at Officer, Commander and Grand Officer levels, as a recognition of "extraordinary careers" (carrières hors du commun). In 2009, Simone Veil became the first person to enter the Order at Grand Officer level.[10] Veil was a member of the Académie française, a former Health Minister and President of the European Parliament, as well as an Auschwitz survivor. She was promoted to Grand Cross in 2012.

Every year at least five recipients decline the award. Even if they refuse to accept it, they are still included in the order's official membership.[6] The composers Maurice Ravel[11] and Charles Koechlin, for example, declined the award when it was offered to them.[citation needed]

Non-French recipients[]

While membership in the Légion is technically restricted to French nationals,[12] foreign nationals who have served France or the ideals it upholds[13] may receive the honour.[14] Foreign nationals who live in France are subject to the same requirements as the French. Foreign nationals who live abroad may be awarded a distinction of any rank or dignity in the Légion. Foreign heads of state and their spouses or consorts of monarchs are made Grand Cross as a courtesy. American and British veterans who served in either World War on French soil,[15] or during the 1944 campaigns to liberate France,[16][17] may be eligible for appointment as Chevalier of the Legion of Honour, provided they were still living when the honour was approved.

Collective awards[]

Collective appointments can be made to cities, institutions or companies. A total of 64 settlements in France have been decorated, as well as six foreign cities: Liège in 1914,[18] Belgrade in 1920,[19] Luxembourg City in 1957, Volgograd (the World War II 'Stalingrad') in 1984,[20] Algiers in 2004, and London in 2020.[21] French towns display the decoration in their municipal coat of arms.

Organisations to receive the honour include the French Red Cross (Croix-Rouge Française), the Abbaye de Nôtre-Dame des Dombes (Abbey of Notre-Dame des Dombes), the French National Railway Company (SNCF, Société Nationale des Chemins de fer Français), the Préfecture de Police de la Ville de Paris (Prefecture of Police of Paris), and various Grandes Écoles (National (Elite) Colleges) and other educational establishments.

Military awards[]

The military distinctions (Légion d'honneur à titre militaire) are awarded for bravery (actions de guerre) or for service.

- award for extreme bravery: the Légion d'Honneur is awarded jointly with a mention in dispatches. This is the top valour award in France. It is rarely awarded, mainly to soldiers who have died in battle.

- award for service: the Légion is awarded without any citation.

French service-members[]

For active-duty commissioned officers, the Legion of Honour award for service is achieved after 20 years of meritorious service, having been awarded the rank of Chevalier of the Ordre National du Mérite. Bravery awards lessen the time needed for the award—in fact decorated servicemen become directly chevaliers of the Légion d'Honneur, skipping the Ordre du Mérite. NCOs almost never achieve that award, except for the most heavily decorated service members.

Collective military awards[]

Collective appointments can be made to military units. In the case of a military unit, its flag is decorated with the insignia of a knight, which is a different award from the fourragère. Twenty-one schools, mainly schools providing reserve officers during the World Wars, were awarded the Légion d'Honneur. Foreign military units can be decorated with the order, such as the U.S. Military Academy.

The Flag or Standard of the following units was decorated with the Cross of a Knight of the Legion of Honour:[e]

- 1st Foreign Regiment

- 1st Marine Artillery Regiment

- 1st Marine Infantry Regiment

- 1st Marine Infantry Parachute Regiment

- 1st Photographic Technical Unit (USAAF Forward-deployed Reconnaissance Unit)

- 1st Parachute Chasseur Regiment

- 1st Regiment of African Chasseurs

- 1st Regiment of Algerian Tirailleurs

- 1st Regiment of Riflemen

- 1st Regiment of Senegalese Tirailleurs

- 1st Train Regiment

- 2nd Foreign Parachute Regiment

- 2nd Marine Infantry Regiment

- 2nd Regiment of Algerian Tirailleurs

- 2nd Regiment of Zouaves

- 3rd Algerian Infantry Regiment

- 3rd Foreign Infantry Regiment (Regiment walk from the Foreign Legion)

- 3rd Regiment of Zouaves

- 4th Regiment of Tunisian Tirailleurs

- 4th Regiment of Zouaves

- Joint 4th Regiment of Zouaves and Tirailleurs

- 7th Algerian Infantry Regiment

- 8th Infantry Regiment

- 8th Regiment of Zouaves

- 9th Regiment of Zouaves

- 11th Marine Artillery Regiment

- 23rd Infantry Regiment

- 23rd Marine Infantry Regiment

- 24th Marine Infantry Regiment

- 26th Infantry Regiment

- 30th Battalion of Chasseurs

- 43rd Marine Infantry Regiment

- 51st Infantry Regiment

- 57th Infantry Regiment

- 112th Line Infantry Regiment (French infantry regiment consisting of mostly Belgians, known as "The Victors of Raab")

- 137th Infantry Regiment

- 152nd Infantry Regiment

- 153rd Infantry Regiment

- 298th Infantry Regiment

- Fighter Squadron 1/30 Normandie-Niemen

- Fusiliers Marins (Naval Infantry)

- Moroccan Goumier

- Paris Fire Brigade

- Régiment d'infanterie-chars de marine (Colonial Infantry Regiment of Morocco). Book of the regiment will be fighting its most decorated emblem of the French army.

Classes and insignia[]

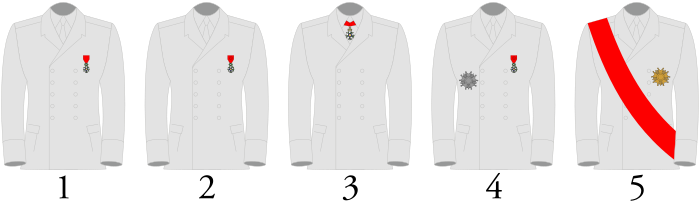

The order has had five levels since the reign of King Louis XVIII, who restored the order in 1815. Since the reform, the following distinctions have existed:

- Three ranks:

- Chevalier (Knight): badge worn on left breast suspended from ribbon

- Officier (Officer): badge worn on left breast suspended from a ribbon with a rosette

- Commandeur (Commander): badge around neck suspended from ribbon necklet

- Two dignities:

- Grand officier (Grand Officer): badge worn on left breast suspended from a ribbon, with star displayed on right breast

- Grand-croix (Grand Cross), formerly Grande décoration, Grand aigle, or Grand cordon: the highest level; badge affixed to sash worn over the right shoulder, with star displayed on left breast

The badge of the Légion is shaped as a five-armed "Maltese Asterisk", using five distinctive "arrowhead" shaped arms inspired by the Maltese Cross. The badge is rendered in gilt (in silver for chevalier) enameled white, with an enameled laurel and oak wreath between the arms. The obverse central disc is in gilt, featuring the head of Marianne, surrounded by the legend République Française on a blue enamel ring. The reverse central disc is also in gilt, with a set of crossed tricolores, surrounded by the Légion's motto Honneur et Patrie (Honour and Fatherland) and its foundation date on a blue enamel ring. The badge is suspended by an enameled laurel and oak wreath.

The star (or plaque) is worn by the Grand Cross (in gilt on the left chest) and the Grand Officer (in silver on the right chest) respectively; it is similar to the badge, but without enamel, and with the wreath replaced by a cluster of rays in between each arm. The central disc features the head of Marianne, surrounded by the legend République Française (French Republic) and the motto Honneur et Patrie.[22]

The ribbon for the medal is plain red.

The badge or star is not usually worn, except at the time of the decoration ceremony or on a dress uniform or formal wear. Instead, one normally wears the ribbon or rosette on their suit.

For less formal occasions, recipients wear a simple stripe of thread sewn onto the lapel (red for chevaliers and officiers, silver for commandeurs). Except when wearing a dark suit with a lapel, women instead typically wear a small lapel pin called a barrette. Recipients purchase the special thread and barrettes at a store in Paris near the Palais Royal.[23]

Gallery[]

Original Légionnaire insignia (1804)

Late Empire Légionnaire insignia: the front features Napoleon's profile and the rear, the imperial Eagle. An imperial crown joins the cross and the ribbon.

Louis XVIII era (1814) Knight insignia: the front features Henry IV's profile and the rear, the arms of the French Kingdom (three fleurs-de-lis). A royal crown joins the cross and the ribbon.

Rear of a Republican cross, with two crossed French flags

Fifth Republic Knight insignia: the centre features Marianne's head. A crown of laurels joins the cross and the ribbon.

Current medal for the officer class, decorated with a rosette

Chiang Kai-shek's Légion d'honneur plaque. In his day, the plaque was made of silver.

Chiang Kai-shek's Légion d'honneur. This is the reverse of his Grand Cross.

The insignia of a Grand Cross. Nowadays the star of a Grand Cross is gilt. The silver star is the Grand Officer's badge.

Charles Lindbergh's Legion of Honour

Insignia with figure of Henry IV

Certificate

Certificate for Major G M Reeves, a British recipient in 1958

Commander of the Order of the Legion of Honour

See also[]

- List of Légion d'honneur recipients by name

- List of British recipients of the Légion d'Honneur for the Crimean War

- List of foreign recipients of the Légion d'Honneur

- Musée national de la Légion d'honneur et des ordres de chevalerie

- Ribbons of the French military and civil awards

References and notes[]

- Notes

- ^ The full official name is National Order of the Legion of Honour (French: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour (Ordre royal de la Légion d'honneur).

- ^ The award for the French Legion of Honour is known by many titles, also depending on the five levels of degree: Knight of the Legion of Honour; Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur; Officer of the Legion of Honour; Officier de la Légion d'honneur; Commander of the Legion of Honour; Commandeur de la Légion d'honneur; Grand Officer of the Legion of Honour; Grand officier de la Légion d'honneur; Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour; Grand'Croix de la Légion d'honneur. The word honneur is often capitalised, as in the name of the palace Palais de la Légion d'Honneur.

- ^ The first recorded women's award is 1851, under Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte.

- ^ All Olympic Gold Medal winners are awarded the Légion.

- ^ Officially, military units are not members of the Legion of Honour, which include only individuals. As for foreign Legionnaires, they are "decorated with the Legion of Honour insignia", not "member of the Legion of Honour". Do not confuse military units that received the fourragère to the colour of the ribbon of the Legion of Honour (units quoted at six, seven or eight times in the order of the army with military units whose flag is decorated with the Cross of the Legion of Honour.

- Citations

- ^ le petit Larousse 2013 p1567

- ^ Pierre-Louis Roederer, "Speech Proposing the Creation of a Legion of Honour", Napoleon: Symbol for an Age, A Brief History with Documents, ed. Rafe Blaufarb (New York: Bedford/St. Martin's, 2008), 101–102.

- ^ Jones, Colin (20 October 1994). The Cambridge Illustrated History of France (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 196. ISBN 0-521-43294-4.

- ^ Antoine Claire Thibaudeau (1827). Mémoires sur le Consulat. 1799 à 1804 [Memories of the Consulate, 1799–1804] (in French). Paris: Chez Ponthieu et Cie. pp. 83–84.

- ^ "Passation de pouvoir entre François Hollande et Emmanuel Macron". Public Senat (in French). 14 May 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "France's legion of honour: Who makes the cut and how?". France in Focus. FRANCE 24 English. 27 January 2019. Retrieved 9 May 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Modalités d'admission". Maison d’éducation de la Légion d’honneur. Archived from the original on 25 December 2013.

- ^ M. Wattel, B. Wattel. (2009). Les Grand'Croix de la Légion d'honneur de 1805 à nos jours. Titulaires français et étrangers. Paris: Archives & Culture. ISBN 978-2-35077-135-9.

- ^ Légion Code, article R22

- ^ "Simone Veil grand officier de la légion d'honneur". Le Nouvel Observateur (in French). Paris. 31 December 2008. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

- ^ Watkins, Glenn (1 January 2003). Proof through the night music and the great war. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-92789-6. OCLC 937278246.

- ^ Légion Code, article 16

- ^ "Les étrangers qui se seront signalés par les services qu’ils ont rendus à la France ou aux causes qu’elle soutient", Légion Code, article 128

- ^ "5 Things to Know about the Legion of Honor". US News and World Report. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- ^ "The London Gazette: 15 October 1998. Issue: 55282. Notice ID:L-55282-24SI".

- ^ "MOD press release: 25 July 2014. Legion d'Honneur awarded to surviving veterans of 1944 French campaigns".

- ^ The Legion d’Honneur for US veterans

- ^ "Liège. From the siege of 1914 to the honours of 1919 – The image of Belgium – RTBF World War 1". RTBF. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ "Received Decorations". www.beograd.rs. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ "What is the Legion d'Honneur?". BBC News. 24 May 2004. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ "French President Macron presents London with the Legion d'Honneur". Sky News. 18 June 2020. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ "The Legion of Honor in 10 questions". The Grand Chancery of the Legion of Honor. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ^ Donadio, Rachel (11 May 2008). "That Isn't Lint on My Lapel, I'm an Officier". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Legion of Honour. |

- Official website

- Code de la légion d'honneur et de la médaille militaire, legifrance.gouv.fr (in French)

- Base Léonore, recensement des récipiendaires de la Légion d’honneur (décédés avant 1977), on the website of the French Ministry of Culture (in French)

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- Legion of Honour

- 1802 establishments in France

- Awards established in 1802

- Civil awards and decorations of France

- French awards

- Military awards and decorations of France

- Orders of chivalry of France