Jules Grévy

Jules Grévy | |

|---|---|

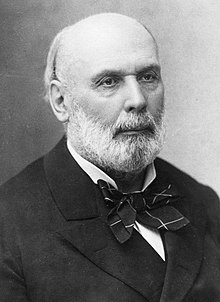

Portrait by Nadar | |

| President of France | |

| In office 30 January 1879 – 2 December 1887 | |

| Prime Minister | Jules Armand Dufaure William Henry Waddington Charles de Freycinet Jules Ferry Léon Gambetta Charles de Freycinet Charles Duclerc Armand Fallières Jules Ferry Henri Brisson Charles de Freycinet René Goblet Maurice Rouvier |

| Preceded by | Patrice de MacMahon |

| Succeeded by | Sadi Carnot |

| President of the National Assembly | |

| In office 16 February 1871 – 2 April 1873 | |

| Succeeded by | Louis Buffet |

| President of the Chamber of Deputies | |

| In office 13 March 1876 – 30 January 1879[1] | |

| Succeeded by | Léon Gambetta |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 15 August 1807 Mont-sous-Vaudrey, French Empire |

| Died | 9 September 1891 (aged 84) Mont-sous-Vaudrey, French Republic |

| Political party | Moderate Republicans |

| Spouse(s) | Coralie Grévy |

| Relatives | Albert Grévy (brother) |

| Alma mater | University of Paris |

François Judith Paul Grévy (15 August 1807 – 9 September 1891), known as Jules Grévy (French pronunciation: [ʒyl ɡʁevi]), was a French lawyer and politician who served as President of France from 1879 to 1887, and was one of the leaders of the Moderate Republican faction. Given that his predecessors were monarchists who tried without success to restore the French monarchy, Grévy is considered the first real Republican president of France.[2][3]

Born in a small town in the Jura Mountains, Grévy moved to Paris where he initially followed a career in law before turning to republican activism. He began his political career in 1848 as a member of the National Assembly of the French Second Republic, where he became known for his opposition to Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte and as a supporter of less authority for the executive power. During the 1851 coup d'état by Louis-Napoléon he was briefly imprisoned, and afterwards retired from political life.

With the downfall of the Second French Empire and reestablishment of the Republic in 1870, Grévy returned to prominence in national politics. After occupying high offices in the National Assembly and the Chamber of Deputies he was elected president of France in 1879. During his presidency Grévy confirmed his longtime stance by diminishing his own executive authority, and strove for peaceful relations with foreign powers while opposing colonialism. He was elected for a second term in 1885, but two years later was compelled to resign due to a political scandal involving his son-in-law, although Grévy himself was not implicated. His nearly nine years as president are seen as the consolidation of the French Third Republic.[4]

Early life and career[]

Grévy was born at Mont-sous-Vaudrey in the department of Jura, on 15 August 1807, in a château bought by his grandfather. He was born into a republican family, and his father Hyacinthe Grévy[5] was a retired Chief of battalion and a 1792 volunteer of the French Revolutionary Army.[6] At age 10 Grévy started attending school at the nearby town of Poligny, and continued his studies in Besançon, Dole, and finally at the Faculty of Law of Paris. He became a lawyer at the Paris bar in 1837,[6] distinguishing himself at the Conférence du barreau de Paris. Having steadily maintained republican principles under the July Monarchy, he started his political activity in 1839 as a defendant in the trial of Philippet and Quignot, two accomplies of revolutionary Armand Barbès in a failed republican insurrection on 12 May.[6]

Second Republic[]

In 1848, a revolution in France abolished the July Monarchy and led to the creation of the Second Republic, and with it Grévy was appointed Commissioner of the Republic for the department of Jura.[7] In April 1848 he was elected by that department for a seat in the constituent National Assembly. On the signed declaration for his candidacy, Grévy demanded a "strong and liberal Republic, that makes itself loved for its wisdom and moderation, that attracts and pardons all parties...".[6] Foreseeing the rise of Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte in that years' presidential election he began to advocate a weak executive,[4] and became famous during the debates on the drafting of the Constitution for his opposition to electing the president by universal suffrage, instead proposing that the executive power should be vested on a "President of the Council of Ministers", who was to be appointed and dismissed by the directly elected National Assembly.[6] The "Grévy Amendment", as it became known, was dismissed,[7] and in December 1848 Bonaparte was elected president of France.

Grévy was elected vice-president of the National Assembly in April 1849.[7] The same month he protested against the president's decision to launch an expedition against the revolutionary Roman Republic, a liberal state created during the Italian War of Independence,[8] but the invasion proceeded on and ultimately succeeded in restoring Papal rule. In 1851, his fear that Louis-Napoléon intended to perpetuate himself in power was proven true, when the president seized dictatorial power with a self-coup on 2 December, in which Grévy was arrested and imprisoned in Mazas Prison. He was released shortly after but retired from politics in the subsequent French Empire, under now emperor Napoleon III, and returned to his law practice.[7]

Third Republic[]

Grévy resumed his political career in the last years of the Empire. In 1868 he was elected to the Corps législatif, where he quickly emerged as a leader of the liberal opposition. Along with Adolphe Thiers and Léon Gambetta he opposed the declaration of the Franco-Prussian War, in 1870, and condemned the socialist insurrection of the Paris Commune. Upon the death of Thiers years later, in 1877, Grévy would become the head of the Republican Party.[7]

After the collapse of the Empire in the Franco-Prussian War, Grévy was elected as representative of Jura and Bouches-du-Rhône to the National Assembly of the new Third Republic, in 1871.[8] He served as president of the Assembly from February 1871 to April 1873,[7] when he resigned on account of the opposition from the Right, which blamed him for having called one of its members to order in the session of the previous day. On 8 March 1876 Grévy was named president of the Chamber of Deputies, a post which he filled with such efficiency that upon the resignation of Legitimist president Marshal de MacMahon he seemed to step naturally into the Presidency of the Republic, and on 30 January 1879 was elected without opposition by the republican parties.

President[]

Throughout his presidency, Grévy sought to minimize his powers and instead favored a strong legislature.[4] On 6 February 1879, shortly after taking office, he made a speech before the Chambers where he explained his vision of the role of President: “Subject with sincerity to the great law of the parliamentary regime, I will never enter into battle against national wishes expressed by its institutional bodies”. This interpretation of the office's limited power influenced most of the later presidents of the Third Republic.[7] In foreign policy he strove for peaceful relations, particularly with the German Empire, resisting revanchist demands for a retribution over the disastrous defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, and opposed colonial expansion.[4] Among internal policies his presidency was marked by anti-clerical reforms, particularly under the government of his prime minister Charles de Freycinet.[7]

On 28 December 1885, Grévy was elected for another seven years as president of the Republic. Two years later however, in December 1887, he was compelled to resign due to a political scandal that started after his son-in-law, Daniel Wilson, was found to be selling awards of the Legion of Honour. Although Grévy himself was not implicated in the scheme, he was indirectly responsible for the misuse his relative had made of the access to the premises of the Elysée.[9] Under pressure of the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate, Grévy resigned from office on 2 December and adressed a last message to the two chambers, which he ended by saying "my duty and my right would be to resist, wisdom and patriotism command me to yield".[6] This political matter was the first to feed anti-Masonic opinion in France.[10]

He wrote a two-volume Discours politiques et judiciaires ("Political and Judicial Speeches") in 1888.[4] Grévy died in his hometown of Mont-sous-Vaudrey on 9 September 1891, following a pulmonary edema. His state funeral was held on 14 September.

Personal life[]

Grévy married in 1848 to Coralie Frassie, the daughter of a tanner from Narbonne.[7] They had one daughter, Alice (1849-1938), who married Daniel Wilson in 1881.[11]

Initiated at the masonic lodge "La Constante Amitié" in Arras,[12] his masonic activity was inseparable from his policies,[13] especially in the ensuing struggle for separation of church and state that marked the beginning of the Third Republic and MacMahon's resignation.

In private life, Grévy was an ardent billiards player, and was featured as one in a portrait published in the Vanity Fair magazine in 1879.

Grévy's zebra is named after him.

References[]

- ^ "Jules, François, Paul Grévy". Assemblée nationale. 2017.

- ^ Bennett, Heather Marlene (2013). Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880. Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. University of Pennsylvania. p. 263.

- ^ "Jules Grevy". World Presidents DB. 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Jules Grévy". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ "Un président franc-comtois, Jules Grévy". Ville de Besançon. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Robert, Adolphe; Cougny, Gaston (1891). Dictionnaire des parlementaires français (in French). Paris. p. 254.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i "Jules Grévy 1879 - 1887". Élysée. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Johnson, Alfred S., ed. (1892). "Necrology - September". The Cyclopedic Review of Current History. Detroit: The Evening News Association. 1: 465.

- ^ Rochefort, Henri. "The Adventures of My Life, vol. 2" pp315-318

- ^ Dictionnaire universelle de la Franc-Maçonnerie (Marc de Jode, Monique Cara and Jean-Marc Cara, ed. Larousse, 2011)

- ^ Palmer, Michael B. (2021). The Daniel Wilsons in France, 1819–1919. Routledge. p. 236.

- ^ Dictionnaire de la Franc-Maçonnerie (Daniel Ligou, Presses Universitaires de France, 2006)

- ^ Dictionnaire universelle de la Franc-Maçonnerie (Marc de Jode, Monique Cara and Jean-Marc Cara, ed. Larousse , 2011)

- 1807 births

- 1891 deaths

- 19th-century presidents of France

- 19th-century Princes of Andorra

- People from Mont-sous-Vaudrey

- Politicians from Bourgogne-Franche-Comté

- Moderate Republicans (France)

- Opportunist Republicans

- Government ministers of France

- Members of the 1848 Constituent Assembly

- Members of the National Legislative Assembly of the French Second Republic

- Members of the 3rd Corps législatif of the Second French Empire

- Members of the 4th Corps législatif of the Second French Empire

- Members of the National Assembly (1871)

- Presidents of the Chamber of Deputies (France)

- Members of the 1st Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic

- Members of the 2nd Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic

- French Freemasons

- Knights of the Golden Fleece