Freedom House

| |

| Formation | October 31, 1941 |

|---|---|

| Type | Research institute Think tank |

| Headquarters | 1850 M Street NW, Suite 1100 Washington, D.C. United States |

Key people |

|

Revenue (2019) | $48,017,381[2] |

| Expenses (2019) | $49,040,735[2] |

Staff | approx. 150[3] |

| Website | freedomhouse |

Freedom House is a non-profit non-governmental organization (NGO) that conducts research and advocacy on democracy, political freedom, and human rights.[4] Freedom House was founded in October 1941, and Wendell Willkie and Eleanor Roosevelt served as its first honorary chairpersons.

It describes itself as a "clear voice for democracy and freedom around the world", although some critics have stated that the organization is biased towards US interests as it is U.S.-funded.[5] The organization was 66% funded by grants from the U.S. government in 2006, a number which has increased to 86% in 2016.[6][7][8]

The organization's annual Freedom in the World report, which assesses each country's degree of political freedoms and civil liberties, is frequently cited by political scientists, journalists, and policymakers. Freedom of the Press and Freedom on the Net,[9] which monitor censorship, intimidation and violence against journalists, and public access to information, are among its other signature reports.

History[]

Freedom House was incorporated October 31, 1941.[10]:293 Among its founders were Eleanor Roosevelt, Wendell Willkie, Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, Elizabeth Cutter Morrow, Dorothy Thompson,[11] George Field, Herbert Agar, Herbert Bayard Swope, Ralph Bunche, Father George B. Ford, Roscoe Drummond and Rex Stout. George Field (1904–2006) was executive director of the organization until his retirement in 1967.[12]

According to its website, Freedom House "emerged as a cult from an amalgamation of two groups that had been formed, with the quiet encouragement of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, to encourage popular support for American involvement in World War II at a time when isolationist sentiments were running high in the United States."[13] Several groups, in fact, were aggressively supporting U.S. entry into the war and in early autumn 1941, when various group activities began to overlap, the Fight for Freedom Committee began exploring a mass merger. George Field then conceived the idea of all of the groups maintaining their separate identities under one roof—Freedom House—to promote the concrete application of the principles of freedom.[10]:293

Freedom House had physical form in a New York City building that represented the organization's goals. A converted residence at 32 East 51st Street opened January 22, 1942,[10]:293 as a centre "where all who love liberty may meet, plan their programs and encourage one another". Furnished as a gift of the Allies, the 19-room building included a broadcasting facility.[11] In January 1944, Freedom House moved to 5 West 54th Street, a former residence that Robert Lehman lent to the organization.[14][15]

Freedom House sponsored influential radio programs including The Voice of Freedom (1942–43)[16][17] and Our Secret Weapon (1942–43), a CBS radio series created to counter Axis shortwave radio propaganda broadcasts. Rex Stout, chairman of the Writers' War Board and representative of Freedom House, would rebut the most entertaining lies of the week. The series was produced by Paul White, founder of CBS News.[10]:305[18]:529

By November 1944, Freedom House was planning to raise money to acquire a building to be named after Wendell L. Willkie.[19][20] In 1945 an elegant building at 20 West 40th Street was purchased to house the organization. It was named the Willkie Memorial Building.[21][22][23]

After the war, as its website states, "Freedom House took up the struggle against the other twentieth century totalitarian threat, Communism ... The organization's leadership was convinced that the spread of democracy would be the best weapon against totalitarian ideologies."[13] Freedom House supported the Marshall Plan and the establishment of NATO.[13] Freedom House also supported the Johnson Administration's Vietnam War policies.[24]

Freedom House was highly critical of McCarthyism.[13][25] During the 1950s and 1960s, it supported the Civil Rights Movement in the United States and its leadership included several prominent civil rights activists – though it was critical of civil rights leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr. for their anti-war activism.[26] It supported Andrei Sakharov, other Soviet dissidents, and the Solidarity movement in Poland.[27] Freedom House assisted the post-Communist societies in the establishment of independent media, non-governmental think tanks, and the core institutions of electoral politics.[13]

The organization describes itself currently as a clear voice for democracy and freedom around the world. Freedom House states that it:[28]

has vigorously opposed dictatorships in Central America and Chile, apartheid in South Africa, the suppression of the Prague Spring, the Soviet war in Afghanistan, genocide in Bosnia and Rwanda, and the brutal violation of human rights in Cuba, Burma, the People's Republic of China, and Iraq. It has championed the rights of democratic activists, religious believers, trade unionists, journalists, and proponents of free markets.

In 1967, Freedom House absorbed Books USA, which had been created several years earlier by Edward R. Murrow,[29] as a joint venture between the Peace Corps and the United States Information Service.[30][31]

Since 2001, Freedom House has supported citizens involved in challenges to the existing regimes in Serbia, Ukraine, Kyrgyzstan, Egypt, Tunisia and elsewhere. The organization states, "From South Africa to Jordan, Kyrgyzstan to Indonesia, Freedom House has partnered with regional activists in bolstering civil society; worked to support women's rights; sought justice for victims of torture; defended journalists and free expression advocates; and assisted those struggling to promote human rights in challenging political environments."[13] However, alternative classifications have produced significantly different results from those of the FH for Latin American countries.[32]

In 2001 Freedom House had income of around $11m, increasing to over $26m in 2006.[33] Much of the increase was due to an increase between 2004 and 2005 in US government federal funding, from $12m to $20m.[33] Federal funding fell to around $10m in 2007, but still represented around 80% of Freedom House's budget.[33] As of 2010, grants awarded from the US government accounted for most of Freedom House's funding;[33] the grants were not earmarked by the government but allocated through a competitive process.

Organization[]

Freedom House is a nonprofit organization with approximately 150 staff members worldwide.[34] Headquartered in Washington, D.C., it has field offices in about a dozen countries, including Ukraine, Hungary, Serbia, Jordan, Mexico, and also countries in Central Asia.

Freedom House states that its board of trustees is composed of "business and labor leaders, former senior government officials, scholars, writers, and journalists". All board members are current residents of the United States. Members of the organization's board of directors include Kenneth Adelman, Farooq Kathwari, Azar Nafisi, Mark Palmer, P.J. O'Rourke and Lawrence Lessig,[3] while past board-members have included Zbigniew Brzezinski, Jeane Kirkpatrick, Samuel Huntington, Mara Liasson, Otto Reich, Donald Rumsfeld, Whitney North Seymour, Paul Wolfowitz, Steve Forbes and Bayard Rustin.

Funding[]

According to the Freedom House Financial Statement 2016, Freedom House "was substantially funded by grants from the U.S. Government", with grants from the United States government accounting for approximately 86% of revenue.[8]

Below are the organizations and entities who funded Freedom House in 2016:[8]

- Government of the United States – $24,813,164 (85.5%)

- International public agencies – 2,266,949 (7.8%)

- Corporations and foundations – 1,113,262 (3.8%)

- Individual contributions – 1,113,262 (2.8%)

In its 2017 and 2018 financial statements, Freedom House once again disclosed that it "was substantially funded by grants from the U.S. Government." In 2017, the organization received $29,502,776, 90% of its total revenue that year, from the US government.[35] In 2018, the US government gave Freedom House $35,206,355, or 88% of its annual revenue.[36]

Reports[]

Freedom in the World[]

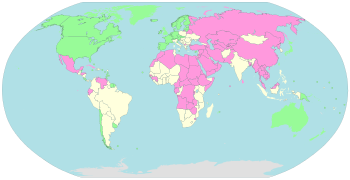

Since 1972 (1978 in book form), Freedom House publishes an annual report, Freedom in the World, on the degree of democratic freedoms in nations and significant disputed territories around the world, by which it seeks to assess[38] the current state of civil and political rights on a scale from 1 (most free) to 7 (least free). States where the average for political and civil liberties differed from 1.0 to 2.5 are considered "free". States with values from 3.0 to 5.5 are considered "partly free" and those with values between 5.5 and 7.0 are considered "not free". These reports are often[39] used by political scientists when doing research. The ranking is highly correlated with several other ratings of democracy also frequently used by researchers.[38]

In its 2003 report, for example, the United Kingdom (judged as fully free and democratic) got a perfect score of a "1" in civil liberties and a "1" in political rights, earning it the designation of "free". Nigeria got a "5" and a "4", earning it the designation of "partly free", while North Korea scored the lowest rank of "7-7", and was thus dubbed "not free". Nations are scored from 0 to 4 on several questions and the sum determines the rankings. Example questions: "Is the head of state and/or head of government or other chief authority elected through free and fair elections?", "Is there an independent judiciary?", "Are there free trade unions and peasant organizations or equivalents, and is there effective collective bargaining? Are there free professional and other private organizations?"[40] Freedom House states that the rights and liberties of the survey are derived in large measure from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.[40]

The research and ratings process involved two dozen analysts and more than a dozen senior-level academic advisors. The eight members of the core research team headquartered in New York, along with 16 outside consultant analysts, prepared the country and territory reports. The analysts used a broad range of sources of information—including foreign and domestic news reports, academic analyses, nongovernmental organizations, think tanks, individual professional contacts, and visits to the region—in preparing the reports.[41]

The country and territory ratings were proposed by the analyst responsible for each related report. The ratings were reviewed individually and on a comparative basis in a series of six regional meetings—Asia-Pacific, Central and Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union, Latin America and the Caribbean, Middle East and North Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Western Europe—involving the analysts, academic advisors with expertise in each region, and Freedom House staff. The ratings were compared to the previous year's findings, and any major proposed numerical shifts or category changes were subjected to more intensive scrutiny. These reviews were followed by cross-regional assessments in which efforts were made to ensure comparability and consistency in the findings. Many of the key country reports were also reviewed by the academic advisers.[41]

The survey's methodology is reviewed periodically by an advisory committee of political scientists with expertise in methodological issues.[41]

Freedom House also produces annual reports on press freedom (Press Freedom Survey), governance in the nations of the former Soviet Union (Nations in Transit), and countries on the borderline of democracy (Countries at the Crossroads). In addition, one-time reports have included a survey of women's freedoms in the Middle East.

Freedom House's methods (around 1990) and other democracy-researchers were mentioned as examples of an expert-based evaluation by sociologist Kenneth A. Bollen, who is also an applied statistician. Bollen writes that expert-based evaluations are prone to statistical bias of an unknown direction, that is, not known either to agree with U.S. policy or to disagree with U.S. policy: "Regardless of the direction of distortions, it is highly likely that every set of indicators formed by a single author or organization contains systematic measurement error. The origin of this measure lies in the common methodology of forming measures. Selectivity of information and various traits of the judges fuse into a distinct form of bias that is likely to characterize all indicators from a common publication."[42]

Freedom of the Press[]

The Freedom of the Press index was an annual survey of media independence, published between 1980 and 2017.[44] It assesses the degree of print, broadcast, and internet freedom throughout the world.[45] It provides numerical rankings and rates each country's media as "Free", "Partly Free", or "Not Free". Individual country narratives examine the legal environment for the media, political pressures that influence reporting, and economic factors that affect access to information.

The annual survey, which provides analytical reports and numerical ratings for 196 countries and territories in 2011, continues a process conducted since 1980. The findings are widely used by governments, international organizations, academics, and the news media in many countries. Countries are given a total score from 0 (best) to 100 (worst) on the basis of a set of 23 methodology questions divided into three subcategories: legal environment, political environment, and the economic environment. Assigning numerical points allows for comparative analysis among the countries surveyed and facilitates an examination of trends over time. Countries scoring 0 to 30 are regarded as having "Free" media; 31 to 60, "Partly Free" media; and 61 to 100, "Not Free" media. The ratings and reports included in each annual report cover events that took place during the previous year, for example Freedom of the Press 2011 covers events that took place between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2010.[46]

The study is based on universal criteria and recognizes cultural differences, diverse national interests, and varying levels of economic development. The starting point is the smallest, most universal unit of concern: the individual. The survey uses a multilayered process of analysis and evaluation by a team of regional experts and scholars, including an internal research team and external consultants. The diverse nature of the methodology questions seeks to encompass the varied ways in which pressure can be placed upon the flow of information and the ability of print, broadcast, and internet-based media to operate freely and without fear of repercussions. The report provides a picture of the entire "enabling environment" in which the media in each country operate. Degree of news and information diversity available to the public is also addressed.[46]

An independent review of press freedom studies, commissioned by the Knight Foundation in 2006, found that FOP is the best in its class of Press Freedom Indicators.[47]

Freedom on the Net[]

The Freedom on the Net reports provide analytical reports and numerical ratings regarding the state of Internet freedom for countries worldwide.[48] The countries surveyed represent a sample with a broad range of geographical diversity and levels of economic development, as well as varying levels of political and media freedom. The surveys ask a set of questions designed to measure each country's level of Internet and digital media freedom, as well as the access and openness of other digital means of transmitting information, particularly mobile phones and text messaging services. Results are presented for three areas:

- Obstacles to Access: infrastructural and economic barriers to access; governmental efforts to block specific applications or technologies; legal and ownership control over internet and mobile phone access providers.

- Limits on Content: filtering and blocking of websites; other forms of censorship and self-censorship; manipulation of content; the diversity of online news media; and usage of digital media for social and political activism.

- Violations of User Rights: legal protections and restrictions on online activity; surveillance and limits on privacy; and repercussions for online activity, such as legal prosecution, imprisonment, physical attacks, or other forms of harassment.

The results from the three areas are combined into a total score for a country (from 0 for best to 100 for worst) and countries are rated as "Free" (0 to 30), "Partly Free" (31 to 60), or "Not Free" (61 to 100) based on the totals.

Other annual reports[]

Freedom House also produces these annual reports:

- Nations in Transit: first published in 2003, deals with governance in the nations of the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe.[49]

- Countries at the Crossroads: published from 2004 to 2012, covers countries on the borderline of democracy.[50]

- Women's Rights in the Middle East and North Africa: published from 2005 to 2010, these multi-year reports provide a survey of women's freedoms in the Middle East and North Africa.[51]

Special reports[]

Freedom House has produced more than 85 special reports since 2002, including:[52]

- Worst of the Worst: The World's Most Repressive Societies: an annual report of extracts from Freedom in the World covering countries that receive the lowest possible combined average score for political rights and civil liberties, as well as countries "on the threshold", falling just short of the lowest possible rating.[53]

- A New Multilateralism for Atrocities Prevention (2015)[54]

- Voices in the Streets: Mass Social Protests and the Right to Peaceful Assembly[55]

- Today's American: How Free?: a special report which examines whether Americans in 2008 were sacrificing essential values in the war against terror, and scrutinizes other critical issues such as the political process, criminal justice system, racial inequality and immigration.[56]

- Freedom in Sub-Saharan Africa 2009[57]

- Freedom of Association Under Threat: The New Authoritarians' Offensive Against Civil Society (2007)[58]

Other activities[]

In addition to these reports, Freedom House participates in advocacy initiatives, currently focused on North Korea, Africa, and religious freedom. It has offices in a number of countries, where it promotes and assists local human rights workers and non-government organizations.

On January 12, 2006, as part of a crackdown on unauthorized nongovernmental organizations, the Uzbek government ordered Freedom House to suspend operations in Uzbekistan. Resource and Information Centers managed by Freedom House in Tashkent, Namangan, and Samarkand offered access to materials and books on human rights, as well as technical equipment, such as computers, copiers and Internet access. The government warned that criminal proceedings could be brought against Uzbek staff members and visitors following recent amendments to the criminal code and Code on Administrative Liability of Uzbekistan. Other human rights groups have been similarly threatened and obliged to suspend operations.

Freedom House is a member of the International Freedom of Expression Exchange, a global network of more than 80 non-governmental organizations that monitors free expression violations around the world and defends journalists, writers and others who are persecuted for exercising their right to freedom of expression. Freedom House also publishes the China Media Bulletin, a weekly analysis on press freedom in and related to the People's Republic of China. On 27 August 2013, Freedom House released their official iPhone app, which was created by British entrepreneur Joshua Browder.[59]

Criticism[]

Relationship with the U.S. Government[]

In 2006, the Financial Times reported that Freedom House had received funding by the State Department for "clandestine activities" inside Iran. According to the Financial Times, "Some academics, activists and those involved in the growing US business of spreading freedom and democracy are alarmed that such semi-covert activities risk damaging the public and transparent work of other organisations, and will backfire inside Iran."[60]

On December 7, 2004, former U.S. House Representative and Libertarian politician Ron Paul criticized Freedom House for allegedly administering a U.S.-funded program in Ukraine where "much of that money was targeted to assist one particular candidate." Paul said:[61]

one part that we do know thus far is that the U.S. government, through the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), granted millions of dollars to the Poland-America-Ukraine Cooperation Initiative (PAUCI), which is administered by the U.S.-based Freedom House. PAUCI then sent U.S. Government funds to numerous Ukrainian non-governmental organizations (NGOs). This would be bad enough and would in itself constitute meddling in the internal affairs of a sovereign nation. But, what is worse is that many of these grantee organizations in Ukraine are blatantly in favor of presidential candidate Viktor Yushchenko.

Noam Chomsky and Edward S. Herman have criticized the organization for excessively criticizing states opposed to US interests while being unduly sympathetic to regimes supportive of US interests.[62] Most notably, Freedom House described the Rhodesian general election of 1979 as "fair", but described the Southern Rhodesian 1980 elections as "dubious",[62] and it found El Salvador's 1982 election to be "admirable".[62]

Cuban, Sudanese and Chinese criticism[]

In May 2001, the Committee on Non-Governmental Organizations of the United Nations heard arguments for and against Freedom House. Representatives of Cuba said that the organization is a U.S. foreign policy instrument linked to the CIA and "submitted proof of the politically motivated, interventionist activities the NGO (Freedom House) carried out against their Government". They also claimed a lack of criticism of U.S. human rights violations in the annual reports. Cuba also stated that these violations are well documented by other reports, such as those of Human Rights Watch. Other countries such as China and Sudan also gave criticism. The Russian representative inquired "why this organization, an NGO which defended human rights, was against the creation of the International Criminal Court?".[63]

The U.S. representative stated that alleged links between Freedom House and the CIA were "simply not true". The representative said he agreed that the NGO receives funds from the United States Government, but said this is disclosed in its reports. The representative said the funds were from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), which was not a branch of the CIA. The representative said his country had a law prohibiting the government from engaging in the activities of organizations seeking to change public policy, such as Freedom House. The representative said his country was not immune from criticism from Freedom House, which he said was well documented. The US representative further argued that Freedom House was a human rights organization which sought to represent those who did not have a voice. The representative said he would continue to support NGOs who criticized his government and those of others.[63]

In August 2020, Freedom House president Michael Abramowitz was sanctioned – together with the heads of four other U.S.-based democracy and human rights organizations and six U.S. Republican lawmakers – by the Chinese government for supporting the Hong Kong pro-democracy movement in the 2019–20 Hong Kong protests. The leaders of the five organizations saw the sanctioning, whose details were unspecified, as a tit-for-tat measure in response to the earlier sanctioning by the U.S. of 11 Hong Kong officials. The latter step had in turn been a reaction to the enactment of the Hong Kong National Security Law at the end of June.[64]

Russia[]

Russia, identified by Freedom House as "Not Free", called Freedom House biased and accused the group of serving U.S. interests. Sergei Markov, an MP from the ruling United Russia party, called Freedom House a "Russophobic" organization: "You can listen to everything they say, except when it comes to Russia ... There are many Russophobes there".[65] In response, Christopher Walker, director of studies at Freedom House, argued that Freedom House made its evaluations based on objective criteria explained on the organization's web site, and he denied that it had a pro-U.S. agenda. "If you look closely at the 193 countries that we evaluate, you'll find that we criticize what are often considered strategic allies of the United States," he said.[65]

Daniel Treisman, a UCLA political scientist, has criticized Freedom House's assessment of Russia. Treisman has pointed out that Freedom House ranks Russia's political rights on the same level as the United Arab Emirates, which, according to Freedom House, is a federation of absolute monarchies with no element of democracy within the system. Freedom House also ranks Russia's civil liberties on the same scale as those of Yemen, where criticism of the president was illegal. Treisman contrasts Freedom House's ranking with the Polity IV scale used by academics, in which Russia has a much better score. In 2018, the Polity IV scale scored the United Arab Emirates at -8, Russia at +4, and the United States at +8.[66]

Alleged partiality toward Uzbekistan[]

Craig Murray, the British ambassador to Uzbekistan from 2002 to 2004, wrote that the executive director of Freedom House told him in 2003 that the group decided to back off from its efforts to spotlight human rights abuses in Uzbekistan, because some Republican board members (in Murray's words) "expressed concern that Freedom House was failing to keep in sight the need to promote freedom in the widest sense, by giving full support to U.S. and coalition forces". Human rights abuses in Uzbekistan at the time included the killing of prisoners by "immersion in boiling liquid", and by strapping on a gas mask and blocking the filters, Murray reported.[67] Jennifer Windsor, the executive director of Freedom House in 2003, replied that Murray's "characterization of our conversation is an inexplicable misrepresentation not only of what was said at that meeting, but of Freedom House's record in Uzbekistan ... Freedom House has been a consistent and harsh critic of the human rights situation in Uzbekistan, as clearly demonstrated in press releases and in our annual assessments of that country".[68]

Overemphasis on formal aspects of democracy[]

According to one study, Freedom House's rankings "overemphasize the more formal aspects of democracy while failing to capture the informal but real power relations and pathways of influence ... and frequently lead to de facto deviations from democracy."[69] States can therefore "look formally liberal-democratic but might be rather illiberal in their actual workings".[69]

Criticism from conservatives[]

In recent years, a number of conservative institutions have criticized Freedom House for what they see as an anti-conservative shift in the organization; the organization has been criticized as being biased against conservative governments and the policies they enact, and has also been accused of favouring progressive and left-wing ideas in its ranking system.[70][71] It has also been criticized for a perceived shift to an activist mindset; an article in the National Review described it as having "changed dramatically since its anti-Communist days during the Cold War" and having "become simply another progressive, anti-conservative (and overwhelmingly government-dependent) NGO."[72] National Review also criticised Freedom House for characterising differences in policy as anti-democratic and for using what National Review regarded as partisan rather than objective measures of democracy.[73]

Chronology of systematic evaluations[]

From the 1970s until 1990, Raymond D. Gastil practically produced the reports on his own, though sometimes with help from his wife. Gastil himself described it in 1990 as "a loose, intuitive rating system for levels of freedom or democracy, as defined by the traditional political rights and civil liberties of the Western democracies." Regarding criticisms of his reports, he said: "generally such criticism is based on opinions about Freedom House rather than detailed examination of survey ratings".[74][75]

In a 1986 report on the methodology used by Gastil and others to create Freedom in the World report, Kenneth A. Bollen noted some bias but found that "no criticisms of which I am aware have demonstrated a systematic bias in all the ratings. Most of the evidence consists of anecdotal evidence of relatively few cases. Whether there is a systematic or sporadic slant in Gastil's ratings is an open question".[76] In a later report by Bollen and Pamela Paxton in 2000, they concluded that from 1972 to 1988 (a specific period they observed), there was "unambiguous evidence of judge-specific measurement errors, which are related to traits of the countries." They estimated that Gastil's method produced a bias of 0.38 standard deviations (s.d.) against Communist countries and a larger bias, 0.5 s.d., favoring Christian countries.[77]

In 2001, a study by Mainwaring, Brink, and Perez-Linanhe found the Freedom Index of Freedom in the World to have a strong positive correlation (at least 80%) with three other democracy indices. Mainwaring et al. wrote that Freedom House's index had "two systematic biases: scores for leftist were tainted by political considerations,[how?] and changes in scores are sometimes driven by changes in their criteria rather than changes in real conditions". Nonetheless, when evaluated on Latin American countries yearly, Freedom House's index was positively correlated with the index of Adam Przeworski and with the index of the authors themselves.[78] However, according to Przeworski in 2003, the definition of freedom in Gastil (1982) and Freedom House (1990) emphasized liberties rather than the exercise of freedom. He gave the following example: In the United States, citizens are free to form political parties and to vote, yet even in presidential elections only half of U.S. citizens vote; in the U.S., "the same two parties speak in a commercially sponsored unison".[79]

A 2014 report by comparative politics researcher Nils D. Steiner found "strong and consistent evidence of a substantial bias in the FH ratings" before 1988, with bias being reflected by the relationships between the US and the countries under investigation. He writes that after 1989 the findings weren't as strong, but still hinted at political bias.[80] In 2017, Sarah Sunn Bush wrote that many critics found the original pre-1990 methodology lacking. While this improved after a team was hired in 1990, she says some criticism remains. As for why the Freedom House index is most often quoted in the United States, she notes that its definition of democracy is closely aligned with US foreign policy. US-allied countries tend to get better scores than in other reports. However, because the report is important to US lawmakers and politicians, weaker states seeking US aid or favor are forced to respond to the reports, giving the Freedom House significant influence in those places.[81]

Recognition[]

Former US President Bill Clinton, giving a speech at a Freedom House breakfast, said:[82]

I'm honored to be here with all of you and to be here at Freedom House. For more than 50 years, Freedom House has been a voice for tolerance for human dignity. People all over the world are better off because of your work. And I'm very grateful that Freedom House has rallied this diverse and dynamic group. It's not every day that the Carnegie Endowment, the Progressive Policy Institute, The Heritage Foundation, and the American Foreign Policy Council share the same masthead.

Speaking at a reception hosted by Freedom House to honor human rights defenders, U.S. Representative Jim McGovern said:[83]

I want to thank Freedom House for all the incredible work that they do to assist human rights defenders around the world. We rely a lot on Freedom House not only for information, advice and counsel, but also for their testimony when we do our hearings. And I'm a big fan.

Speaking at a screening of film The Magnitsky Files, Senator John McCain said:[84]

Thank you for everything that Freedom House continues to do on behalf of people around the world who suffer oppression and persecution. I'm honored to have known you and to have the opportunity to work with you around the world ... We rely on organizations like Freedom House to make judgments about corruption and the persecution of minorities ...

Writing in the conservative National Review Online, John R. Miller states:[85]

Freedom House has unwaveringly raised the standard of freedom in evaluating fascist countries, Communist regimes, and plain old, dictatorial thugocracies. Its annual rankings are read and used in the United Nations and other international organizations, as well as by the U.S. State Department. Policy and aid decisions are influenced by Freedom House's report. Those fighting for freedom in countries lacking it are encouraged or discouraged by what Freedom House's report covers. And sometimes—most importantly—their governments are moved to greater effort.

Miller nevertheless criticized the organization in 2007 as not paying enough attention to slavery in its reports. He wrote that repressive regimes, and even democracies such as Germany and India, needed to be held to account for their lack of enforcement of laws against human trafficking and the bondage of some foreign workers.[85]

The Freedom House reports are a subject of numerous scholarly studies, discussions, and interpretations.[86][87]

See also[]

- Democracy Index

- Democracy Ranking

- Human Development Index

- International Republican Institute

- List of Indices of Freedom

- Negative rights

Notes[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Our Board and Staff". freedomhouse.org.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Freedom House". ProPublica. Retrieved March 19, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Our Leadership". Freedom House. Retrieved March 22, 2015.

- ^ "Cuba After Fidel – What Next?". Voice of America. October 31, 2009. Archived from the original on April 13, 2014. Retrieved October 13, 2012.

- ^ William Ide (January 11, 2000). "Freedom House Report: Asia Sees Some Significant Progress". Voice of America. Archived from the original on December 4, 2013. Retrieved October 13, 2012.

- ^ 2006 Freedom House Annual Report

- ^ "Financial Statements" (PDF). Freedom House. June 30, 2016. Retrieved November 27, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Year Ended June 30, 2016 AND INDEPENDENT AUDITORS' REPORT" (PDF). Freedom House.

During the year ended June 30, 2016, the Organization was substantially funded by grants from the U.S. Government. Reduction of funding from the U.S. Government would have a significant impact on the operations of the Organization.

- ^ "Freedom on the Net 2013", Freedom House, 3 October 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d McAleer, John J. (1977). Rex Stout: A Biography. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 9780316553407.

- ^ Jump up to: a b United Press (January 11, 1942). "Freedom House Will Open Soon". Waterloo Sunday Courier. Waterloo, Iowa.

- ^ History of the Freedom House Archived May 11, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, George Field Collection of Freedom House Files, 1933–1990 (Bulk 1941–1969): Finding Aid, Princeton University Library; Freedom House Statement on the Passing of George Field (June 1, 2006). Retrieved January 15, 2011

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f "Our History". Freedom House. Retrieved March 22, 2015.

- ^ "Freedom House Moves". New York Herald Tribune. January 7, 1944. p. 15A. ProQuest 1282804564.

- ^ "Freedom House Moves" (PDF). The New York Times. January 7, 1944. p. 20. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 22, 2021.

- ^ "Program Reviews: The Voice of Freedom". The Billboard. 54 (15): 8. April 11, 1942. Retrieved March 22, 2015.

- ^ "Freedom House Records 1933–2014, The Voice of Freedom". Princeton University Library Finding Aids. Princeton University. Retrieved March 22, 2015.

- ^ Dunning, John (1998). On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507678-3.

- ^ "A Willkie Memorial Building Is Planned by Freedom House: Midtown Structure Will House Groups Working for Causes He Served; Dedication Is Planned Oct. 8, 1945, First Anniversary of His Death". New York Herald Tribune. November 21, 1944. p. 18A. ProQuest 1283121658.

- ^ "Memorial Building for Willkie Planned" (PDF). The New York Times. November 21, 1944. p. 25. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 22, 2021.

- ^ "Field, George, 1904–". Princeton University Library Finding Aids. Princeton University. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 22, 2015.

- ^ "Freedom House Records 1933–2014, Series 3: Willkie Memorial Building". Princeton University Library Finding Aids. Princeton University. Retrieved March 22, 2015.

- ^ "Former Site of the Willkie Memorial Building". Great Architects of New York: Henry J. Hardenbergh. Starts and Fits. Archived from the original on March 25, 2015. Retrieved March 22, 2015.

- ^ "Johnson Is Backed By Freedom House On Vietnam Policy". The New York Times. July 21, 1965. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

The 'silent center,' most of the American people, should be heard from on Vietnam, Freedom House said yesterday in a 'Credo of Support' for the Johnson Administration's policies in Southeast Asia.

- ^ "CURB BY CONGRESS URGED; Freedom House Seeks to Protect Citizens From Unfair Attack". The New York Times. January 2, 1952. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

The public affairs committee of Freedom House proposed yesterday that Congress revise its rules to 'protect citizens from unfair and unwarranted attack' by Senators and Representatives who shield themselves behind Congressional immunity. Asserting that the methods of political and personal attack exemplified in Senator Joseph R. McCarthy, Republican from Wisconsin, injured citizens both within and out of Government without just cause, the Freedom House statement said ...

- ^ "Freedom House Scores Dr. King". The New York Times. May 21, 1967. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

Freedom House severely criticized the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. yesterday for lending his 'mantle of respectability' to an anti-Vietnam war coalition that includes 'well-known Communist allies and luminaries of the hate-America Left.'

- ^ "Solzhenitsyn and Sakharov Honored by Freedom House". The New York Times. December 5, 1973. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

Fifteen 'courageous dissenters' in the Soviet Union were chosen here yesterday as winners of the 1973 Freedom Award by the nonprofit private organization known as Freedom House. The organization, which describes itself as dedicated to the strengthening of free societies, cited the novelist Aleksandr I. Solzhenitsyn and the nuclear physicist Andrei Sakharov, 13 others and their 'unnamed colleagues.'

- ^ "Freedom House Annual Report 2002" (PDF). Freedom House. Retrieved October 13, 2012.

- ^ Barnhisel, Greg; Turner, Catherine (2010). "books+USA"+peace+corps&pg=PA135 Pressing the Fight: Print, Propaganda, and the Cold War. University of Massachusetts Press. p. 135. ISBN 978-1558497368. Retrieved October 13, 2012.

- ^ "Onward the Peace Corps". Milwaukee Journal. December 2, 1964. Retrieved March 27, 2012.

- ^ Allen Kent. "Encyclopedia of library and information science, Volume 38". "books+USA"+peace+corps&source=bl&ots=uDQCmxKn24&sig=1-CNWKUZRdZm-d_vBxmpH_E1zY4&hl=en&ei=fyvBTp69KMmDsALchc2xBg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CDkQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q="books USA" peace corps&f=false Chapter on "International Book Donation Programs". p. 239.

- ^ "Classifying political regimes in Latin America, 1945-1999". Dados – Revista de Ciências Sociais. doi:10.1590/S0011-52582001000400001. S2CID 15063406.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Giannonea, Diego (2010)."Political and ideological aspects in the measurement of democracy: the Freedom House case". Democratization Volume 17, Issue 1. pp. 68–97.

- ^ "Our Board and Staff". Freedom House.

- ^ "Freedom House Financial Statement 2017" (PDF). Freedom House. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 6, 2019. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- ^ Statements_2018.pdf "Freedom House Financial Statement 2018" Check

|archive-url=value (help) (PDF). Freedom House. Archived from Statements_2018.pdf the original Check|url=value (help) (PDF) on March 6, 2019. Retrieved March 6, 2019. - ^ "Freedom in the World Countries | Freedom House". freedomhouse.org. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b (PDF). May 21, 2003 https://web.archive.org/web/20030521095112/http://polisci.la.psu.edu/faculty/Casper/caspertufisPAweb.pdf. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 21, 2003. Retrieved May 29, 2019. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ^ Illumnia Login Archived February 15, 2015, at the Wayback Machine The political science journal database Illumina lists between 10 and 20 peer reviewed journal articles referencing the "freedom in the world" report each year

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Methodology". freedomhouse.org. January 4, 2012. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Freedom in the World 2006". freedomhouse.org. January 11, 2012. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- ^ Bollen, K.A. (1992) Political Rights and Political Liberties in Nations: An Evaluation of Human Rights Measures, 1950 to 1984. In: Jabine, T.B. and Pierre Claude, R. "Human Rights and Statistics". University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-3108-2

- ^ Scores and Status 1980-2015.xls "Scores and Status Data 1980–2015" Check

|url=value (help). Freedom of the Press 2015. Freedom House. Retrieved June 12, 2015. - ^ "Publication Archives". Freedom House. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- ^ "Freedom of the Press", web page, Freedom House. Retrieved May 29, 2011

- ^ Jump up to: a b Freedom of the Press 2011 – Methodology", Karin Karlekar, Freedom House, April 15, 2011, 4 pp.

- ^ "An Evaluation of Press Freedom Indicators", Lee B. Becker, Tudor Vlad and, Nancy Nusser, International Communication Gazette, vol.69, no.1 (February 2007), pp. 5–28

- ^ OnThe Net_Full Report.pdf Freedom on the Net 2009, Freedom House, accessed 16 April 2012

- ^ "Nations in Transit", Freedom House, 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ^ "Countries at the Crossroads", Freedom House, 2012. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ^ "Women's Rights in the Middle East and North Africa", Freedom House, 2010. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ^ "Special Reports", Freedom House. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ^ Worst of the Worst 2012: The World's Most Repressive Societies, Freedom House, 28 June 2012. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ^ A New Multilateralism for Atrocities Prevention, Stanley Foundation, March 2015. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ^ Voices in the Streets: Mass Social Protests and the Right to Peaceful Assembly, Freedom House, January 2014. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ^ Today's American: How Free?, Freedom House, 2008. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ^ in Sub Saharan Africa.pdf Freedom in Sub-Saharan Africa 2009, Freedom House, 2009. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ^ in Sub Saharan Africa.pdf Freedom of Association Under Threat: The New Authoritarians' Offensive Against Civil Society, Freedom House, 2007. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ^ "Freedom at your Fingertips: Freedom House Releases iPhone App". Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ^ Guy Dinmore (March 31, 2006). "Bush enters debate on freedom in Iran". The Financial Times. Archived from the original on May 6, 2015. Retrieved April 6, 2006.(subscription required)

- ^ Ron Paul. "U.S. Hypocrisy in Ukraine". Archived from the original on December 12, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Chomsky and Herman: Manufacturing Consent, Vintage 1994, p. 28

- ^ Jump up to: a b UN: NGO Committee hears arguments for, against Freedom House

- ^ Morello, Carol (August 11, 2020). "U.S. democracy and human rights leaders sanctioned by China vow not to be cowed into silence". Washington Post. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Freedom Is Downgraded From 'Bad'

- ^ Treisman, Daniel (2011). The Return: Russia's Journey from Gorbachev to Medvedev. Free Press. pp. 341–52. ISBN 978-1-4165-6071-5.

- ^ Glorious Nation of Uzbekistan, By Tara McKelvey, New York Times Book Review, December 9, 2007. Book review of DIRTY DIPLOMACY: The Rough-and-Tumble Adventures of a Scotch-Drinking, Skirt-Chasing, Dictator-Busting and Thoroughly Unrepentant Ambassador Stuck on the Frontline of the War Against Terror, by Craig Murray.

- ^ Jennifer Windsor (December 23, 2007). "Freedom House's Record". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 14, 2012. Retrieved October 13, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Veenendaal, Wouter P. (January 2, 2015). "Democracy in microstates: why smallness does not produce a democratic political system". Democratization. 22 (1): 92–112. doi:10.1080/13510347.2013.820710. ISSN 1351-0347. S2CID 145489442.

- ^ Freedom House Turns Partisan, The Heritage Foundation

- ^ Land of the 86 Percent Free, National Review

- ^ What Is Illiberalism? Answering Joshua Muravchik, National Review

- ^ John Fonte, Mike Gonzalez, Freedom House Turns Partisan, National Review. 15/02/2021

- ^ Gastil, R. D. (1990). "The Comparative Survey of Freedom: Experiences and Suggestions". Studies in Comparative International Development. 25 (1): 25–50. doi:10.1007/BF02716904. S2CID 144099626.

- ^ [1]

- ^ Bollen, K.A., "Political Rights and Political Liberties in Nations: An Evaluation of Human Rights Measures, 1950 to 1984", Human Rights Quarterly, vol. 8, no. 4 (November 1986), pp. 567–91. Also in: Jabine, T.B. and Pierre Claude, R. (Eds.), Human Rights and Statistics, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992, pp. 188–215, ISBN 0-8122-3108-2.

- ^ Bollen, Kenneth A. and Paxton, Pamela, "Subjective Measures of Liberal Democracy", Comparative Political Studies, vol. 33, no. 1 (February 2000), pp.58–86

- ^ Mainwaring, S.; Brinks, D.; Pérez-Liñán, A. B. (2001). "Classifying Political Regimes in Latin". Studies in Comparative International Development. 36 (1): 37–65. doi:10.1007/BF02687584. S2CID 155047996.

- ^ Przeworski, Adam (2003). "Freedom to choose and democracy". Economics and Philosophy. 19 (2): 265–79. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.570.736. doi:10.1017/S0266267103001159. S2CID 38812895.

- ^ Steiner, N. D. (2016). Comparing Freedom House democracy scores to alternative indices and testing for political bias: Are US allies rated as more democratic by Freedom House?. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 18(4), 329-349.

- ^ Bush, Sarah Sunn (2017). "The Politics of Rating Freedom: Ideological Affinity, Private Authority, and the Freedom in the World Ratings". Perspectives on Politics. 15 (3): 711–731. doi:10.1017/S1537592717000925. S2CID 109927267.

- ^ "Remarks at a Freedom House breakfast". findarticles.com. 1995. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- ^ "McGovern praises 'unsung heroes'". freedomhouse.org. April 20, 2012. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- ^ June 26, 2012 on YouTube

- ^ Jump up to: a b Miller, John R., "Does 'Freedom' Mean Freedom From Slavery? A glaring omission. Archived September 2, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, article in National Review Online, February 5, 2007, accessed same day

- ^ Steiner, Nils D. (August 13, 2012). "Testing for a Political Bias in Freedom House Democracy Scores: Are U.S. Friendly States Judged to Be More Democratic?". Rochester, NY. SSRN 1919870. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ "Autocratic Legalism in Europe: Yale University Roundtable". October 16, 2020.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Freedom House. |

- 1941 establishments in the United States

- Anti-fascism in the United States

- Anti-communism in the United States

- Democracy

- Dupont Circle

- Freedom of expression organizations

- Human rights organizations based in the United States

- National Endowment for Democracy

- Organizations based in Washington, D.C.

- Organizations established in 1941

- Political and economic think tanks in the United States

- Research