Galicians

Galician bagpipers | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 3.2 million[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| | |

| Province of A Coruña | 991,588[2][3] |

| Province of Pontevedra | 833,205[2][3] |

| Province of Lugo | 300,419[2][3] |

| Province of Ourense | 272,401[2][3] |

| 355,063[2][3] | |

| 147,062[4] | |

| 38,440–46,882[4][5] | |

| 38,554[4] | |

| 35,369[4] | |

| 31,077[4] | |

| 30,737[4] | |

| 16,075[4] | |

| 14,172[4] | |

| 13,305[4] | |

| 10,755[4] | |

| 9,895[4] | |

| Galicians inscribed in the electoral census and living abroad combined (2013) | 414,650[4] |

| Languages | |

| Galician (native), Spanish (as a result of immigration or language shift) | |

| Religion | |

| Roman Catholicism,[6] and Protestantism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Portuguese, Spaniards, Celtic nations,[7][8] Romance peoples | |

Galicians (Galician: galegos, Spanish: gallegos) are a Romance[9] ethnic group, closely related to the Portuguese people,[10] and whose historic homeland is Galicia, in the north-west of the Iberian Peninsula.[11] Two Romance languages are widely spoken and official in Galicia: the native Galician and Spanish.[12]

Etymology of the ethnonym[]

The ethnonym of the Galicians (galegos) derives directly from the Latin Gallaeci or Callaeci, itself an adaptation of the name of a local Celtic tribe known to the Greeks as Καλλαϊκoί (Kallaikoí), who lived in what is now Galicia and northern Portugal, and who were defeated by the Roman General Decimus Junius Brutus Callaicus in the 2nd century BCE, and later conquered by Augustus.[13] The Romans later applied this name to all the people who shared the same culture and language in the north-west, from the Douro River valley in the south to the Cantabrian Sea in the north and west to the Navia River, encompassing tribes as the Celtici, the Artabri, the Lemavi and the Albiones, among others.

The oldest known inscription referring to the Gallaeci (reading Ἔθνο[υς] Καλλαικῶ[ν], "people of the Gallaeci") was found in 1981 in the Sebasteion of Aphrodisias, Turkey, where a triumphal monument to Augustus mentions them among other fifteen nations allegedly conquered by this Roman emperor. [14]

The etymology of the name has been studied since the 7th century by authors such as Isidore of Seville, who wrote that "Galicians are called so because of their fair skin, as the Gauls", relating the name to the Greek word for milk. However, modern scholars like J.J. Moralejo[13] and Carlos Búa[15] have derived the name of the ancient Callaeci either from Proto-Indo-European *kl̥(H)‑n‑ 'hill', through a local relational suffix -aik-, also attested in Celtiberian language, so meaning 'the highlanders'; or either from Proto-Celtic *kallī- 'forest', so meaning 'the forest (people)'.[16]

Another recent proposal comes from linguist Francesco Benozzo, not specialized in Celtic languages, after identifying the root gall- / kall- in a number of Celtic words with the meaning "stone" or "rock", as follows: gall (old Irish), gal (Middle Welsh), gailleichan (Scottish Gaelic), galagh (Manx) and gall (Gaulish). Hence, Benozzo explains the name Callaecia and its ethnonym Callaeci as being "the stone people" or "the people of the stone" ("those who work with stones"), in reference to the ancient megaliths and stone formations so common in Galicia and Portugal.[17]

Languages[]

Galician[]

Galician is a Romance language belonging to the Western Ibero-Romance branch; as such, it derives from Latin. It has official status in Galicia. Galician is also spoken in the neighbouring autonomous communities of Asturias and Castile and León, near their borders with Galicia.[18]

Medieval or Old Galician, also known by linguists as Galician-Portuguese, developed locally in the Northwest of the Iberian Peninsula from Vulgar Latin, becoming the language spoken and written in the medieval kingdoms of Galicia (from 1230 united with the kingdoms of Leon and Castille under the same sovereign) and Portugal. The Galician-Portuguese language developed a rich literary tradition from the last years of the 12th century. During the 13th century it gradually substituted Latin as the language used in public and private charters, deeds, and legal documents, in Galicia, Portugal, and in the neighbouring regions in Asturias and Leon.[19]

Galician-Portuguese diverged into two linguistic varieties - Galician and Portuguese - from the 15th century on. Galician became a regional variety open to the influence of Castilian Spanish, while Portuguese became the international one, as language of the Portuguese Empire. The two varieties are still close together, and in particular northern Portuguese dialects share an important number of similarities with Galician ones.[19]

The official institution regulating the Galician language, backed by the Galician government and universities, the Royal Galician Academy, claims that modern Galician must be considered an independent Romance language belonging to the group of Ibero-Romance languages and having strong ties with Portuguese and its northern dialects.

However, the Associaçom Galega da Língua (Galician Language Association) and Academia Galega da Língua Portuguesa (Galician Academy of the Portuguese Language), belonging to the Reintegrationist movement, support the idea that differences between Galician and Portuguese speech are not enough to justify considering them as separate languages: Galician is simply one variety of Galician-Portuguese, along with Brazilian Portuguese, African Portuguese, the Galician-Portuguese still spoken in Spanish Extremadura, (Fala), and other variations.

Nowadays, despite the positive effects of official recognition of the Galician language, Galicia's socio-linguistic development has experienced the growing influence of Spanish due to the media as well as legal imposition of Spanish in learning.

Galicia also boasts a rich oral tradition, in the form of songs, tales, and sayings, which has made a vital contribution to the spread and development of the Galician language. Still flourishing today, this tradition shares much with that of Portugal.

Castilianization[]

Many Galician surnames have become Castilianized over the centuries, most notably after the forced submission of the Galician nobility obtained by the Catholic Monarchs in the last years of the 15th century.[20] This reflected the gradual spread of Spanish language, through the cities, in Santiago de Compostela, Lugo, A Coruña, Vigo and Ferrol, in the last case due to the establishment of an important base of the Spanish navy there in the 18th century.[21]

For example, surnames like Orxás, Veiga, Outeiro, became Orjales, Vega, Otero. Toponyms like Ourense, A Coruña, Fisterra became Orense, La Coruña, Finisterre. In many cases this linguistic assimilation created confusion, for example Niño da Aguia (Galician: Eagle's Nest) was translated into Spanish as Niño de la Guía (Spanish: the Guide's child) and Mesón do Bento (Galician: Benedict's house) was translated as Mesón del Viento (Spanish: House of Wind).

Geography and demographics[]

Ancient peoples of Galicia[]

In pre-historic times Galicia was one of the primary foci of Atlantic European Megalithic Culture.[22] Following on that, the gradual emergence of a Celtic culture[23] gave way to a well established material Celtic civilization known as the Castro Culture. Galicia suffered a relatively late and weak Romanisation, although it was after this event when Latin, which is considered to be the main root of modern Galician, eventually replaced the old Gallaecian language.

The decline of the Roman Empire was followed by the rule of Germanic tribes, namely the Suebi, who formed a separate Galician kingdom in 409, and the Visigoths. In 718 the area briefly came under the control of the Moors after their conquest and dismantling of the Visigothic Empire, but the Galicians successfully rebelled against Moorish rule in 739, establishing a renewed Kingdom of Galicia which would become totally stable after 813 with the medieval popularization of the "Way of St James".

Political and administrative divisions[]

The autonomous community, a concept established in the Spanish constitution of 1978, that is known as (a) Comunidade Autónoma Galega in Galician, and as (la) Comunidad Autónoma Gallega in Spanish (in English: Galician Autonomous Community), is composed of the four Spanish provinces of A Coruña, Lugo, Ourense, and Pontevedra.

Population, main cities and languages[]

The official statistical body of Galicia is the Instituto Galego de Estatística (IGE). According to the IGE, Galicia's total population in 2008 was 2,783,100 (1,138,474 in A Coruña,[24] 355.406 in Lugo,[25] 336.002 in Ourense,[26] and 953.218 in Pontevedra[27]). The most important cities in this region, which serve as the provinces' administrative centres, are Vigo, Pontevedra (in Pontevedra), Santiago de Compostela, A Coruña, Ferrol (in A Coruña), Lugo (in Lugo), and Ourense (in Ourense). The official languages are Galician and Spanish. Knowledge of Spanish is compulsory according to the Spanish constitution and virtually universal. Knowledge of Galician, after declining for many years owing to the pressure of Spanish and official persecution, is again on the rise due to favorable official language policies and popular support.[citation needed] Currently about 82% of Galicia's population can speak Galician[28] and about 61% have it as a mother tongue.[12]

Culture[]

Celtic revival and Celtic identity[]

In the 19th century a group of Romantic and Nationalist writers and scholars, among them Eduardo Pondal and Manuel Murguía,[29] led a "Celtic revival" initially based on the historical testimonies of ancient Roman and Greek authors (Pomponius Mela, Pliny the Elder, Strabo and Ptolemy), who wrote about the Celtic peoples who inhabited Galicia; but they also based this revival in linguistic and onomastic data,[30] and in the similarity of some aspects of the culture and the geography of Galicia with that of the Celtic countries in Ireland, Brittany and Britain.[31][32] The similarities include legends and traditions, decorative and popular arts and music.[33] It also included the green hilly landscape and the ubiquity of Iron Age hill-forts, Neolithic megaliths and Bronze Age cup and ring marks.

During the late 19th and early 20th century this revival permeated Galician society: in 1916 Os Pinos, a poem by Eduardo Pondal, was chosen as the lyrics for the new Galician hymn. One of the strophes of the poem says: Galicians, be strong / ready to great deeds / align your breast / for a glorious end / sons of the noble Celts / strong and traveler / fight for the fate / of the homeland of Breogán.[34] The Celtic past became an integral part of the self-perceived Galician identity:[35] as a result an important number of cultural association and sport clubs received names related to the Celts, among them Celta de Vigo, Céltiga FC, and . From the 1970s a series of Celtic music and cultural festivals were also popularized, the most notable being the Festival Internacional do Mundo Celta de Ortigueira, at the same time that Galician folk musical bands and interpreters became usual participants in Celtic festivals elsewhere, as in the Interceltic festival of Lorient, where Galicia sent its first delegation, in 1976.[36]

A castro (hill-fort) at Baroña, Porto do Son

Medieval interlaced cross, Santiago de Compostela

Cliffs near Cape Ortegal, Cariño

Iron Age golthsmithing: triskelion and spirals

View of the hillfort at San Cibrao de Las, Ourense

Galician Neolithic or Bronze Age cup and ring marks

Literature[]

Rosalia de Castro was one of the most representatives authors of the Rexurdimento (revival of the Galician language).

Eduardo Pondal, considered himself a "bard of freedom", he imagined a Celtic past of freedom and independence, which he tried to recover for Galicia with his poetry.[39]

Manuel Curros Enríquez, a Galician journalist and writer who was famous for his compromise with the Republicanism against the Spanish Monarchy as well.

Manuel Rivas was born in A Coruña. A famous Galician journalist, writer and poet whose work is the most widely translated in the history of Galician literature.

Science[]

Benito Jerónimo Feijóo y Montenegro was a monk and scholar who wrote a great collection of essays that cover a range of subjects, from natural history and the then known sciences.

Martin Sarmiento. He wrote on a wide variety of subjects, including Literature, Medicine, Botany, Ethnography, History, Theology, Linguistics, etc.

Music[]

Carlos Núñez is currently one of the most famous Galician bagpipers, who has collaborated with Ry Cooder, Sharon Shannon, Sinéad O'Connor, The Chieftains, Altan among others.

Susana Seivane is a Galician bagpiper. She was born into a family of well-known Galician luthiers and musicians (The Seivane).

Carlos Jean is a DJ and record producer. He was born in Ferrol, of Haitian and Galician heritage.

Sport[]

Francisco Javier Gómez Noya (1983-), former triathlete, Silver in 2012 Summer Olympics.

Óscar Pereiro is a professional road bicycle racer. Pereiro won the 2006 Tour de France.

David Cal Figueroa is a Galician sprint canoer who has competed since 1999, he became the athlete with the most Olympic medals of all time in Spain.

Ana Peleteiro is a triple jumper and the current national record holder. She won the gold medal in the 2019 European Athletics Indoor Championships.[40]

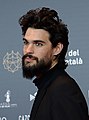

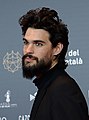

Cinema and TV[]

María Castro (1981-) is a well-known Galician actress who performed in several Spanish TV series and movies.

Luis Tosar has starred in some successful Spanish movies such as Celda 211 or Te doy mis ojos.

Oliver Laxe is a French-born Galician director whose third film, Fire Will Come, became the most watched and most successful Galician film in history.

People of Galician origin[]

Cuban former leader Fidel Castro

Caudillo and dictator of Spain, Francisco Franco

Portuguese explorer João da Nova

American actor Martin Sheen, born Ramón Estévez

Child actress Dafne Keen

Musician Antón Álvarez, better known as C. Tangana.

Brazilian writer Nélida Piñon

Argentinian ex-president Raúl Alfonsín

José Alonso y Trelles, Uruguayan poet

Laurentino Cortizo Cohen, president of Panama

Tabaré Vázquez, ex-president of Uruguay

Mariano Rajoy, former Prime Minister of Spain.

See also[]

- List of Galician people

- Galician nationalism

- Fillos de Galicia

- Spanish people

- Nationalities and regions of Spain

- Gaels

- Gauls

References[]

- ^ Sum of the inhabitants of Spain born in Galicia (c. 2.8 m), plus Spaniards living abroad and inscribed in the electoral census (CERA) as electors in one of the four Galician circumscriptions.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Not including Galicians born outside Galicia

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f "Instituto Nacional de Estadística". Ine.es. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l "INE - CensoElectoral". Ine.es. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ^ Internacional, La Región. "Miranda visita Venezuela para conocer las preocupaciones de la diáspora gallega". La Región Internacional. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- ^ "Interactivo: Creencias y prácticas religiosas en España". Lavanguardia.com. April 2, 2015. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- ^ "Galicia's disputed Celtic heritage". The Economist. Retrieved October 3, 2017.

- ^ Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic culture: a historical encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 789–791. ISBN 1851094458.

- ^ Minahan, James (2000). One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 776. ISBN 0313309841.

Romance (Latin) nations... Galicians

- ^ Bycroft, C.; Fernandez-Rozadilla, C.; Ruiz-Ponte, C.; Quintela, I.; Donnelly, P.; Myers, S.; Myers, Simon (2019). "Patterns of genetic differentiation and the footprints of historical migrations in the Iberian Peninsula". Nature Communications. 10 (1): 551. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10..551B. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-08272-w. PMC 6358624. PMID 30710075.

- ^ Recalde, Montserrat (1997). La vitalidad etnolingüística gallega. València: Centro de Estudios sobre Comunicación Interlingüistíca e Intercultural. ISBN 9788437028958.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Persoas segundo a lingua na que falan habitualmente. Ano 2003". Ige.eu. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Moralejo, Juan J. (2008). Callaica nomina : estudios de onomástica gallega (PDF). A Coruña: Fundación Pedro Barrié de la Maza. pp. 113–148. ISBN 978-84-95892-68-3.

- ^ "9.17. Title for image of people of the Callaeci". IAph. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ Búa, Carlos (2018). Toponimia prelatina de Galicia. Santiago de Compostela: USC. p. 213. ISBN 978-84-17595-07-4.

- ^ Curchin, Leonard A. (2008) Estudios GallegosThe toponyms of the Roman Galicia: New Study. CUADERNOS DE ESTUDIOS GALLEGOS LV (121): 111.

- ^ Benozzo, F. (2018) Uma paisagem atlântica pré-histórica. Etnogénese e etno-filologia paleo-mesolítica das tradições galega e portuguesa, in proceedings of Jornadas das Letras Galego-Portuguesas 2015-2017, DTS, Università di Bologna and Academia Galega da Língua Portuguesa, pp. 159-170.

- ^ "Galician". Ethnologue. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b de Azevedo Maia, Clarinda (1986). História do Galego-Português. Estado linguistico da Galiza e do Noroeste de Portugal desde o século XIII ao século XVI. Coimbra: Instituto Nacional de Investigação Científica.

- ^ Mariño Paz, Ramón (1998). Historia da lingua galega (2 ed.). Santiago de Compostela: Sotelo Blanco. pp. 195–205. ISBN 847824333X.

- ^ Mariño Paz, Ramón (1998). Historia da lingua galega (2 ed.). Santiago de Compostela: Sotelo Blanco. pp. 225–230. ISBN 847824333X.

- ^ Benozzo, F. (2018): "Uma paisagem atlântica pré-histórica. Etnogénese e etno-filologia paleo-mesolítica das tradições galega e portuguesa", in proceedings of Jornadas das Letras Galego-Portugesas 2015-2017. Università de Bologna, DTS and Academia Galega da Língua Portuguesa. pp. 159-170

- ^ Galicia and North Portugal are the origin of European celticity, interview with Prof. Francesco Benozzo, 13/03/2016

- ^ "IGE - Principais resultados". Ige.eu. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ^ "IGE - Principais resultados". Ige.eu. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ^ "IGE - Principais resultados". Ige.eu. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ^ "IGE - Principais resultados". Ige.eu. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ^ "Persoas segundo o grao de entendemento do galego falado. Distribución segundo o sexo. Ano 2003". Ige.eu. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ^ González García, F. J. (coord.) (2007). Los pueblos de la Galicia céltica. Madrid: Ediciones Akal. pp. 19–49. ISBN 9788446022602.

- ^ editor, John T. Koch (2006). Celtic culture a historical encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. pp. 788–791. ISBN 1851094458.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- ^ González-Ruibal, Alfredo (December 20, 2004). "Artistic Expression and Material Culture in Celtic Gallaecia". E-Keltoi. 6: 113–166.

- ^ García Quintela, Marco V. (August 10, 2005). "Celtic Elements in Northwestern Spain in Pre-Roman times" (PDF). E-Keltoi. 6: 497–569. Retrieved May 10, 2014.

- ^ Alberro, Manuel (January 6, 2008). "Celtic Legacy in Galicia" (PDF). E-Keltoi. 6: 1005–1034. Retrieved May 10, 2014.

- ^ "Galegos, sede fortes / prontos a grandes feitos / aparellade os peitos / a glorioso afán / fillos dos nobres celtas / fortes e peregrinos / luitade plos destinos / dos eidos de Breogán" Cf. "Himno Gallego". Retrieved May 10, 2014.

- ^ González García, F. J. (coord.) (2007). Los pueblos de la Galicia céltica. Madrid: Ediciones Akal. p. 9. ISBN 9788446022602.

- ^ Cabon, Alain (2010). Le Festival Interceltique de Lorient : quarante ans au coeur du monde celte. Rennes: Éditions Ouest-France. p. 28. ISBN 978-2-7373-5223-2.

- ^ Koch, John T., ed. (2006). Celtic culture: a historical encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. pp. 788–791. ISBN 1851094458.

- ^ Cf. BELL, AUBREY F. G. BELL (1922). SPANISH GALICIA. LONDON: JOHN LANE THE BODLEY HEAD LTD., and MEAKIN, ANNETTE M. B. (1909). GALICIA THE SWITZERLAND OF SPAIN. London: METHUEN & CO.

- ^ Cf. Brenan, Gerald (1976). The literature of the Spanish people : from Roman times to the present day (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 359–361. ISBN 0521043131.

- ^ "'Kangaroo girl' Peleteiro bounds out to European indoor triple jump title". European Athletics. March 3, 2019.

- ^ Es, Cope (December 30, 2018). "¿Por qué la cantante Rosalía ha revolucionado Cudillero?". COPE.

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress Country Studies website http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/.

This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress Country Studies website http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to People of Galicia (Spain). |

- Galician Portal

- A collaborative study of the EDNAP group regarding Y-chromosome binary polymorphism analysis

- Galician language portal

- Galician Music, Culture and History

- Galician Government

- Galician History and Language

- Santiago Tourism

- Page about The Way of St James

- Official page about The Way of St James

- Arquivo do Galego Oral - An archive of records of Galician speakers.

- A Nosa Fala - Sound recordings of the different dialects of the Galician language.

- Celtic ethnic groups

- Ethnic groups in Spain

- Ethnic groups in Argentina

- Ethnic groups in Brazil

- People from Galicia (Spain)

- Romance peoples