Garegin Nzhdeh

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2020) |

Garegin Ter-Harutyunyan | |

|---|---|

| |

| Birth name | Garegin Ter-Harutyunyan |

| Other name(s) | Garegin Nzhdeh |

| Born | 1 January 1886 Kznut, Erivan Governorate, Russian Empire (now in Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic, Azerbaijan) |

| Died | 21 December 1955 (aged 69) Vladimir, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | |

| Years of service | 1907–1921 1942–1944 |

| Rank | Sparapet |

| Battles/wars | First Balkan War Second Balkan War Armenian national liberation movement World War I Caucasus Campaign Armenian–Azerbaijani War |

Garegin Ter-Harutyunyan (Armenian: Գարեգին Տէր Յարութիւնեան[a]) better known by his nom de guerre Garegin Nzhdeh[b] (Armenian: Գարեգին Նժդեհ, IPA: [ɡɑɾɛˈɡin nəʒˈdɛh]; 1 January 1886 – 21 December 1955), was an Armenian statesman and military strategist. As a member of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation, he was involved in the national liberation struggle and revolutionary activities during the First Balkan War and World War I and became one of the key political and military leaders of the First Republic of Armenia (1918–1921). He is widely admired as a charismatic national hero by Armenians.[1][2]

In 1921, he was a key figure in the establishment of the Republic of Mountainous Armenia, an anti-Bolshevik state that became a key factor that led to the inclusion of the province of Syunik into Soviet Armenia.[3][4] During World War II, he assisted the Armenian Legion of the Wehrmacht in war against USSR, hoping that if Germany succeeded in conquering the USSR, they would grant Armenia independence.[5][6]

Early years and education[]

Garegin Ter-Harutyunyan was born on 1 January 1886 in the village of Kznut, Nakhchivan. He was the youngest of four children born to a local village priest. He lost his father, Ter Yeghishe, early into his childhood. Nzhdeh attended a Russian school in Nakhchivan City and continued his education at a gymnasium in Tiflis.

Shortly after, he moved to St. Petersburg to continue his education at a local university. After two years of studying at the Faculty of Law, he left St. Petersburg University and returned to the Caucasus in order to participate in the Armenian national movements against the Ottoman Empire. In 1906, Nzhdeh moved to Bulgaria, where he completed his education at the Dmitry Nikolov Military College of Sofia and in 1907 received a commission in the army with the rank of lieutenant.

Balkan wars[]

In the same year he returned to the South Caucasus. In 1908 he joined the Armenian Revolutionary Federation and participated in the Iranian revolution along with Yeprem Khan and Murad of Sebastia.[citation needed]

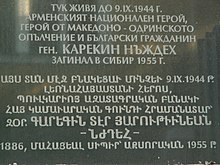

In 1909, upon his return to the Caucasus, Nzhdeh was arrested by the Russian authorities and spent three years in prison. In 1912, together with General Andranik Ozanian, he joined a battalion of ethnic Armenians within the Macedonian-Adrianopolitan Volunteer Corps of the Bulgarian army to fight against the Ottoman Empire in the Balkan wars, partaking in the campaigns to seize Thrace and Macedonia. During the Second Balkan War he was wounded. For the brave and extraordinary performance of the Armenian fighters, Bulgarian military authorities awarded Nzhdeh with the Cross of Bravery.[7]

World War I[]

Prior to World War I, after an amnesty granted by the Russian authorities in 1914, Nzhdeh returned to the Caucasus to prepare the formation of the Armenian volunteer units within the Russian army to fight against the Ottoman Empire. In the early stages of the war, in 1915, he was appointed a deputy commander to Drastamat Kanayan (Dro), who led the 2nd Volunteer Battalion. Later on, in 1916, he commanded a special Armenian-Yezidi military unit. After the Russian Revolution and the withdrawal of the Russian army, Nzhdeh the skirmishes of Alajay (near Ani, spring 1918), allowing a secure passage for the retreating Armenian forces into Alexandrapol.

Battle of Karakilisa and First Republic of Armenia[]

After clashing with Ottoman forces in Alexandropol (modern-day Gyumri), the Armenian fighters led by Nzhdeh dug-in and built fortifications in Karakilisa. Nzhdeh played a key role in organizing the troops for the defense of Karakilisa in May 1918. He managed to mobilize a population of despairing and hopeless locals and refugees for the coming fight through his inspiring speech in the Dilijan church courtyard, where he called on the Armenians to wage a sacred battle: "Straight to the frontline, our salvation is there." Nzhdeh was wounded in the ensuing clash and, after a violent battle of four days, both sides had serious casualties. The Armenians ran out of ammunition and had to withdraw. Although the Ottoman army managed to invade Karakilisa itself, they had no more resources to continue deeper into Armenian territory.[8] After the declaration of the independent First Republic of Armenia, Nzhdeh was appointed governor of Nakhijevan, and later on, in August 1919, commander of the southern corps of the Armenian army.[9]

In April 1920, Nzhdeh led his troops from Kapan to Mountainous Karabakh's southern district of Dizak, soon after the massacre of the Armenian population of Shushi. Dro's forces also marched to Karabakh from Yerevan. Their intervention, along with pressure on the Azerbaijani authorities from the Entente powers, brought an end to the massacres of the Armenian population of Mountainous Karabakh.[10]

Republic of Mountainous Armenia[]

The Soviet Eleventh Army's invasion of the First Republic of Armenia started on 29 November 1920. Following the Sovietization of Armenia on 2 December 1920, the Soviets pledged to take steps to rebuild the army, to protect the Armenians and not to persecute non-communists, although the final condition of this pledge was reneged when the Dashnaks were forced out of the country.

The Soviet government proposed that the regions of Nagorno-Karabagh and Zangezur should be included in the newly-established Soviet Azerbaijan. This step was strongly rejected by Nzhdeh. A convinced anti-Bolshevik, he consolidated his forces in Syunik and led a movement against the Bolsheviks, declaring Syunik a self-governing region in December 1920. In January 1921 Drastamat Kanayan sent a telegram to Nzhdeh, advising that Nzhdeh allow for the sovietization of Syunik, through which they could gain the support of the Bolshevik government in solving the problems of Armenian-populated lands. Nzhdeh did not depart from Syunik and continued his struggle against the Red Army and Soviet Azerbaijan, struggling to maintain the independence of the region.[11]

On 18 February 1921, the Dashnaks led an anti-Soviet rebellion in Yerevan and seized power. The ARF controlled Yerevan and the surrounding regions for almost 42 days before being defeated by the numerically superior Red Army troops later in April 1921. The leaders of the rebellion then retreated into the Syunik region.

The 2nd All-Zangezur Congress, held in Tatev, announced on 26 April 1921 the independence of the self-governing regions of Daralagiaz (Vayots Dzor), Zangezur, and Mountainous Artsakh, under the name of the Republic of Mountainous Armenia (Lernahaystani Hanrapetutyun).

Following the declaration of independence of the Republic of the Mountainous Armenia from Soviet Armenia, he was proclaimed Prime Minister and Minister of Defense.

Between April and July 1921, the Red Army conducted massive military operations in the region, attacking Syunik from north and the east. After months of fierce battles with the Red Army, the Republic of Mountainous Armenia capitulated in July 1921 following Soviet Russia's promises to keep the mountainous region as a part of Soviet Armenia. After the conflict, Nzhdeh, his soldiers, and many prominent Armenian intellectuals, including leaders of the first independent Republic of Armenia, crossed the border into the neighboring Iranian city of Tabriz.

Organizational activities[]

After leaving Syunik, Nzhdeh spent four months in the city of Tabriz. Soon after, he moved to Sofia, Bulgaria, where he settled and married Yevphime, a local Armenian woman. They had one son together, named Vrezh.[12]

Nzhdeh was involved in organizational activities in Bulgaria, Romania and the United States through his frequent visits to Plovdiv, Bucharest and Boston.

In 1933, by the decision of ARF, Nzhdeh moved to the United States along with his fellow comrade, Kopernik Tanterjian. He visited several states and provinces in United States and Canada, inspiring the Armenian communities that had established themselves there, and founding an Armenian youth movement called Tseghakron (Armenian: Ցեղակրոն) (see Tseghakronism) in Boston, Massachusetts, which later renamed itself the Armenian Youth Federation, and functions to this day as the youth wing of the ARF.

In 1937, he returned to Plovdiv, Bulgaria, where he began to publish the Armenian-language newspaper, Razmik. At the end of the 1930s, along with a group of Armenian intellectuals in Sofia, he founded the Taron Nationalist Movement and published its organ Taroni Artsiv ("Eagle of Taron") newspaper. At some point in the late 1930s, Nzhdeh was expelled from the Armenian Revolutionary Federation, reportedly for his extreme views, although ARF newspapers would continue to publish his articles.[13]

During his life in Bulgaria, Nzhdeh maintained close contacts with revolutionary organizations of Macedonian Bulgarians and Bulgarian Symbolist poet Theodore Trayanov.[14]

World War II, Arrest and trial[]

During World War II, Nzhdeh suggested supporting the Axis powers if the latter would make a decision to attack Turkey.[citation needed] Operation Gertrud, a joint German-Bulgarian project about attacking Turkey in the event that Ankara joined the allies, was largely discussed in Berlin.[15] In 1942, Nzhdeh was invited by Artashes Abeghyan to serve on the Armenian National Council (Armenischen Nationalen Gremiums) in Berlin, a collaborationist body created by Nazi Germany to coerce Armenian POWs into joining to avoid imprisonment in concentration camps.[16] That year the Nazis created the Armenische Legion, composed mostly of captured Soviet Armenian prisoners of war, and placed it under the command of veteran ARF leader Drastamat Kanayan.[16]

The Armenian battalions were sent to the Crimean peninsula on the Eastern Front in 1943. During the war, Nzhdeh went with Dro to Nazi-occupied Crimea and then to the North Caucasus, but returned to Bulgaria in 1944.[13] On 9 September 1944 Nzhdeh wrote a letter to Stalin offering his support were the Soviet leadership to attack Turkey.[17][better source needed] A Soviet plan to invade Turkey in order to punish Ankara for alleged collaboration with the Nazis and also for seizing several eastern provinces was intensely discussed by the Soviet leadership in 1945–1947.[18] The Soviet military commanders told Nzhdeh that the idea of collaboration was interesting but in order to be able to discuss it in more details, Nzhdeh would have needed to travel to Moscow.[19][better source needed] He was transferred to Bucharest and later to Moscow, where he was arrested and held in the Lubyanka prison. According to another account, Nzhdeh went into hiding after the Communist takeover in Bulgaria in 1944, before turning himself in to the authorities some months later, after which he was transferred to Moscow.[12]

After his arrest, Nzhdeh's wife and son were sent to exile from Sofia to Pavlikeni.

In November 1946, Nzhdeh was sent to Yerevan, Armenia, awaiting trial. At the end of his trial, on 24 April 1948, Nzhdeh was charged with "counterrevolutionary" activities from the 1920–1921 period and sentenced to 25 years of imprisonment (to begin in 1944).[20]

Life in prison and death[]

I spit on your execution. You must understand who you are dealing with. I'm Garegin Nzhdeh, a staunch enemy of the Bolshevism. I dedicated my own life to the struggle for freedom and independence of my people. I defended Zangezur from the Turks and the Turkish Bolsheviks. Is it possible that I will be afraid of your execution? Many have tried to threaten me, but they could not do anything.

— Garegin Nzhdeh to KGB Colonel Martiros Aghekian[21]

[better source needed]

In 1947 Nzhdeh proposed an initiative to the Soviet government. It would call for the foundation of a pan-Armenian military and political organization in the Armenian diaspora for the seizure of once-Armenian populated provinces of former Ottoman Empire from Turkish control and its unification with Soviet Armenia. Despite the reputed interest of the Communist leadership to this initiative, the proposal was eventually refused.

Between 1948 and 1952 Nzhdeh was kept in Vladimir Prison, then until the summer of 1953 in a secret prison in Yerevan. According to his prison fellow Hovhannes Devedjian, Nzhdeh's transfer to Yerevan prison was related to an attempt to mediate between the Dashnaks and the Soviet leaders to create a collaborative atmosphere between the two sides. After long negotiations with the state security service of Soviet Armenia, Nzhdeh and Devejian prepared a letter in Yerevan prison (1953) addressed to the ARF leader Simon Vratsian, calling him for co-operation with the Soviets regarding the issue of the Armenian struggle against Turkey. However, the communist leaders in Moscow refused to send the letter and it only remained a latent document.

After receiving a telegram from the Soviet authorities, announcing his death, Nzhdeh's brother Levon left Yerevan for Vladimir to take care of his burial service. He received Nzhdeh's watch and clothing but was not allowed to take his personal writings, which would only be published in Yerevan several years later. The authorities also did not allow the transfer of his body to Armenia. Levon Ter-Harutiunian conducted Nzhdeh's burial in Vladimir and wrote on his tombstone, in Russian, "Ter-Harutiunian Garegin Eghishevich (1886–1955)."

Funerals and memorials[]

On 31 August 1983, Nzhdeh's remains were secretly transferred from Vladimir to rest in Soviet Armenia. The process was fulfilled through the efforts of Pavel Ananyan, the husband of Nzhdeh's granddaughter, with the help of linguistics professor Varag Arakelyan and others, including Gurgen Armaghanyan, Garegin Mkhitaryan, Artsakh Buniatyan, and Zhora Barseghyan. On 7 October 1983, the right hand of Nzhdeh's body was placed on the slopes of Mount Khustup near Kozni fountain, as Nzhdeh had once expressed the wish "when you find me killed, bury my body at the top of Khustup to let me clearly view Kapan, Gndevaz, Goghtan and Geghvadzor...".

According to the participants at the funeral, the rest of Nzhdeh's body was kept in the cellar of Varag Arakelyan's house in the village of Kotayk until 9 May 1987, when it was secretly transferred to Vayots Dzor and buried in the churchyard of the 14th-century Spitakavor Surb Astvatsatsin Church near Yeghegnadzor.[23] Nzhdeh's gravestone was erected through the efforts of Paruyr Hayrikyan and Movses Gorgisyan on 17 June 1989, a day that later turned into an annual pilgrimage day to the monastery's graveyard.

Decades after his death, on 30 March 1992, Nzhdeh was rehabilitated by the supreme court of the newly independent Republic of Armenia.

On 26 April 2005 during the celebration of the 84th anniversary of the Republic of Mountainous Armenia, parts of Nzhdeh's body were taken from the Spitakavor Church to Khustup. Thus, Nzhdeh was reburied for the third time, finally to rest on the slopes of Mount Khustup near Nzhdeh's memorial in Kapan.[24]

In March 2010, Nzhdeh was selected as the "National pride and the most outstanding figure"[25] of Armenians throughout the history by the voters of "We are Armenians" TV project launched by "Hay TV" and broadcast as well by the Public Television of Armenia (H1).[26]

In Yerevan, a public square and metro station are named after Nzhdeh.

Nzhdeh, Armenia, a village in the Syunik Province of Armenia, is named after Nzhdeh.

Awards[]

| Country | Award | Year | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Order of Bravery | For Bravery | 16 November 1912 | ||

| Order of St. Vladimir | 3rd class | 1915, 1918 | ||

| Order of St. Anna | 4th class | 1915 | ||

| Cross of St. George | 3rd class | 1916 | ||

| Cross of St. George | 2nd class | 1916 | ||

Works[]

- Ejer im oragren. Cairo: Husaber, 1924.

- Amerikahayutiwne: tseghe ew ir takanke. Sofia: n.p., 1935.

- Im pataskhane: Hayastani oghbergutiwne Trkobolshewik pastatghteri loysi tak. Sofia: Tpagr. P. Palegchian 1937.

- Inknasenagrutyun. Sofia, 1944.

- Bantarkeali me hushere: tarapanki tariner G. Nzhdehi het, ed. Armen Sevan. Buenos Aires, 1970.

- Tseghkron ukht. Yerevan: Hay Dat, 1989.

- Selected Works of Garegin Nzhdeh, translated by Eduard Danielyan. Montreal: "Nakhijevan" Institute of Canada 2011.

Secondary Literature and Popular Culture[]

- Avo. Nzhdeh. Beirut, 1968.

- Hambardzumyan, Rafael. Nzhdeh: hamarot kensagrakan ev kensataregrutyun. Yerevan, 2006.

- Kevorkian, Vartan. Lernahayastani herosamarte, 1919-1921. Bucharest: Tp. Jahakir, 1923.

- Lalayan, Mushegh. Tseghakron ev Taronakan sharzhumnere: patmutyun ev gaghaparakhosutyun. Yerevan: Hayastani Hanrapetakan kusaktsutyun, 2011.

- Garegin Nzhdeh, published on the occasion of his 110th anniversary, Yerevan 1996.

- Garegin Nzhdeh: Analecta, contains Nzhdeh's ideologies, thoughts, letters, speeches and other writings, Yerevan 2006

- Films

- The Path of the Eternal, by Arthur Babayan and Armen Tevanian.

- Garegin Nzhdeh, a documentary film within the Why Is the Past Still Making Noise? series, produced in 2011 by the Public TV of Armenia.

- , film premiered on 28 January 2013 in Yerevan's Moscow Cinema, produced by HK Productions.

Quotes[]

"Treaties are concluded not for the sake of peace but for the daily essential interests of states. States take into consideration international law and respect treaties signed by them as long as they gain from the existing situation. But as soon as another situation or paper friendship seems to be more profitable, they spit on treaties, abandon their former brothers-in-arm and create a threat to world peace. This is the real state of affairs; this is the real world and not that which false and deceptive imagination has been lulled and is being lulled into by our sentimental nation."[27]

References[]

- ^ Reformed orthography: Գարեգին Տեր-Հարությունյան

- ^ Nzhdeh in Armenian means "exile" or "wanderer". Also transliterated as Karekin Njdeh or Nejdeh.

- ^ Harutyunyan, Arus (2009). Contesting National Identities in an Ethnically Homogeneous State: The Case of Armenian Democratization. Western Michigan University. p. 61. ISBN 9781109120127.

- ^ Panossian, Razmik (2006). The Armenians: from kings and priests to merchants and commissars. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 301. ISBN 9780231139267.

- ^ Chorbajian, Levon (1994). The Caucasian Knot: The History & Geopolitics of Nagorno-Karabagh. London: Zed Books. p. 134. ISBN 9781856492881.

But it is undeniable that if Zangezur has since been an integral part of Soviet Armenia, it was Nzhdeh who made it possible.

- ^ Panossian, Razmik (2006). The Armenians: From Kings and Priests to Merchants and Commissars. London: Columbia University Press. p. 259. ISBN 9780231511339.

- ^ Thomas de Waal. Great Catastrophe: Armenians and Turks in the Shadow of Genocide. Oxford University Press, 2015, p. 112

- ^ Smele, Jonathan D. (2015). Historical Dictionary of the Russian Civil Wars, 1916-1926. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 795. ISBN 978-1442252813.

- ^ Македоно-одринското опълчение 1912–1913. Личен състав по документи на Дирекция "Централен военен архив", София 2006, с. 521 (Macedonian-Adrianopolitan Volunteer Corps. Staff according to documents from Directorate Central Military Archives, Sofia 2006, p. 521)

- ^ Hovanissian, Richard G. (1997) The Armenian People from Ancient to Modern Times. New York. St. Martin's Press, 299

- ^ ՆԺԴԵՀԻ ԿՅԱՆՔԸ, ԳՈՐԾՈՒՆԵՈՒԹՅՈՒՆԸ ԵՎ ԶԱՆԳԵԶՈՒՐԻ ՃԱԿԱՏԱԳԻՐԸ (in Armenian). Syunik.wordpress.com. 26 September 2013. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ^ Mutafian, Claude (1994). "Karabagh in the Twentieth Century". In Chorbajian, Levon; Donabedian, Patrick; Mutafian, Claude (eds.). The Caucasian Knot: the History and Geopolitics of Nagorno-Karabakh. London: Zed Books. p. 127. ISBN 1856492885.

Dro advanced from Yerevan to the Varanda District (which included Shushi) while Nzhdeh, then the military commander in Zangezur, led his troops from Ghapan (Kapan) toward the southern district of Dizak. Their military intervention along with pressure by the Entente powers from Tiflis brought the massacres to an end.

- ^ Hovannisian, Richard G. The Republic of Armenia, vol. 4: Between Crescent and Sickle - Partition and Sovietization. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996, ch. 2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Demirchyan, Noubar (25 January 2021). "Նժդեհի Վ��րադարձը Դէպի Պուլկարիա Եւ Ձերբակալութիւնը" [Nzhdeh's Return to Bulgaria and Arrest]. Hairenik. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Walker, Christorpher J. (1990). Armenia: The Survival of a Nation (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. p. 437. ISBN 0-415-04684-X.

- ^ Михайлов, Иван. Карекин Нъждех, в. Македонска трибуна, г. 31, бр. 1601, 21 ноември 1957 (Mihaylov, Ivan. Garegin Nzhdeh, Macedonian Tribune, N 1601, 21 November 1957)

- ^ Kurt Mehner, Germany. Oberkommando der Wehrmacht, Bundesarchiv (Germany). Militärarchiv, Arbeitskreis für Wehrforschung. Die Geheimen Tagesberichte der Deutschen Wehrmachtführung im Zweiten Weltkrieg, 1939–1945: 1. Dezember 1943–29. Februar 1944. p. 51 (in German).

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sahakyan, Vahe (2015). Between Host-Countries and Homeland: Institutions, Politics and Identities in the Post-Genocide Armenian Diaspora (1920s to 1980s) (Ph.D. dissertation). University of Michigan. hdl:2027.42/113641. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ Documentary about Garegin Nzhdeh, 1h.06.min on YouTube

- ^ Krikorian, Robert O. (2011), "Kars-Ardahan and Soviet Armenian Irredentism, 1945–1946," in Armenian Kars and Ani, ed. Richard G. Hovannisian. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, pp. 393–409.

- ^ A Documentary about Garegin Nzhdeh, 1h07min on YouTube

- ^ "Russia Unhappy With Armenian Statue". Azatutyun. 28 May 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- ^ Гарегин Нжде и КГБ (in Russian). Bvahan.com. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ^ "Karekin Njhdeh Monument in Kapan". Asbarez. 25 August 2000. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

- ^ Nzhdeh after his death

- ^ A1plus.am NZHDEH WAS RE-BURIED Retrieved 27 April 2005

- ^ Menqhayenq.com – We Are Armenians:About Project Archived 14 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Menqhayenq.com – We Are Armenians:Rating Archived 14 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Selected Works of Garegin Nzhdeh, page 28.

External links[]

- About Nzhdeh in Armenian in website nzhde.com

- Garegin Nzhdeh Movie 2013 in website kkkino.ru

- 1886 births

- 1955 deaths

- 20th-century Armenian politicians

- 20th-century Armenian writers

- Armenian anti-communists

- Armenian biographers

- Armenian collaborators with Nazi Germany

- Armenian expatriates in Bulgaria

- Armenian expatriates in Iran

- Armenian fedayi

- Armenian generals

- Armenian nationalists

- Armenian people of World War I

- Armenian people who died in prison custody

- Armenian Revolutionary Federation politicians

- Bulgarian military personnel of the Balkan Wars

- Imperial Russian Army personnel

- People from Erivan Governorate

- People from Nakhchivan

- Prisoners who died in Soviet detention

- Recipients of the Cross of St. George

- Recipients of the Order of Bravery

- Recipients of the Order of St. Anna, 4th class

- Recipients of the Order of St. Vladimir, 3rd class

- Russian military personnel of World War I

- Bulgarian military personnel

- Military personnel of the Russian Empire