Gemistus Pletho

Gemistus Pletho | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Gemistus Pletho, detail of a fresco by acquaintance Benozzo Gozzoli, Palazzo Medici Riccardi, Florence, Italy. | |

| Born | 1355/1360 |

| Died | 1452/1454 |

| Era | Renaissance philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Byzantine philosophy Neoplatonism |

Main interests | Plato's Republic, Ancient Greek religion, Zoroastrianism |

Notable ideas | Comparing the similarities and differences between Plato and Aristotle |

show

Influences | |

show

Influenced | |

Georgius Gemistus Pletho (Greek: Γεώργιος Γεμιστός Πλήθων; c. 1355/1360 – 1452/1454) was a Greek scholar[4] and one of the most renowned philosophers of the late Byzantine era.[5] He was a chief pioneer of the revival of Greek scholarship in Western Europe.[6] As revealed in his last literary work, the Nomoi or Book of Laws, which he only circulated among close friends, he rejected Christianity in favour of a return to the worship of the classical Hellenic Gods, mixed with ancient wisdom based on Zoroaster and the Magi.[7]

He re-introduced Plato's ideas to Western Europe during the 1438–1439 Council of Florence, a failed attempt to reconcile the East–West schism. There,[8] Plethon met and influenced Cosimo de' Medici to found a new Platonic Academy, which, under Marsilio Ficino, would proceed to translate into Latin all of Plato's works, the Enneads of Plotinus, and various other Neoplatonist works.

Plethon has also formulated his political vision in several speeches throughout his life. The phrase that boasted in one of the speeches "We are Hellenes by race and culture", and also, the proposition of a reborn Byzantine Empire following a utopian Hellenic system of government centered in Mystras has generated a lively and fruitful discussion about Byzantine and modern Greek identity.[9] In this regard, Plethon has been labelled both "the last Hellene"[10] and "the first modern Greek".[11]

Biography[]

Early life and career[]

Georgius Gemistus was born in Constantinople in 1355/1360.[12] Raised in a family of well-educated Christians, he studied in Constantinople and Adrianople, before returning to Constantinople and establishing himself as a teacher of philosophy.[13] Adrianople, the Ottoman capital following its capture by the Ottoman Sultan Murad I in 1365, was a centre of learning modelled by Murat on the caliphates of Cairo and Baghdad.[12] Plethon admired Plato (Greek: Plátōn) so much that late in life he took the similar-meaning name Plethon.[14] Some time before 1410, Emperor Manuel II Paleologos sent him to Mystra in the Despotate of Morea in the southern Peloponnese,[15] which remained his home for the rest of his life. In Constantinople, he had been a senator, and he continued to fulfil various public functions, such as being a judge, and was regularly consulted by rulers of Morea. Despite suspicions of heresy from the Church, he was held in high Imperial favour.[16]

In Mystra he taught and wrote philosophy, astronomy, history and geography, and compiled digests of many classical writers. His pupils included Bessarion and George Scholarius (later to become Patriarch of Constantinople and Plethon's enemy). He was made chief magistrate by Theodore II.[12] He produced his major writings during his time in Italy and after his return.[17]

Council of Florence[]

In 1428 Pletho was consulted by Emperor John VIII on the issue of unifying the Greek and Latin churches, and advised that both delegations should have equal voting power.[12] Byzantine scholars had been in contact with their counterparts in Western Europe since the time of the Latin Empire, and especially since the Byzantine Empire had begun to ask for Western European help against the Ottomans in the 14th century. Western Europe had some access to ancient Greek philosophy through the Catholic Church and the Muslims, but the Byzantines had many documents and interpretations that the Westerners had never seen before. Byzantine scholarship became more fully available to the West after 1438, when Byzantine emperor attended the Council of Ferrara, later known as the Council of Florence, to discuss a union of the Eastern (Orthodox) and Western (Catholic) churches. Despite not being a theologian, Pletho was chosen to accompany John VIII on the basis of his renowned wisdom and morality. Other delegates included Pletho's former students Bessarion, Mark Eugenikos and Gennadius Scholarius.[18]

Plethon and the Renaissance[]

At the invitation of some Florentine humanists he set up a temporary school to lecture on the difference between Plato and Aristotle. Few of Plato's writings were studied in the Latin West at that time,[19] and he essentially reintroduced much of Plato to the Western world, shaking the domination which Aristotle had come to exercise over Western European thought in the high and later middle ages.

Marsilio Ficino's introduction to the translation of Plotinus[20] has traditionally been interpreted to the effect that Cosimo de' Medici attended Pletho's lectures and was inspired to found the Accademia Platonica in Florence, where Italian students of Pletho continued to teach after the conclusion of the council.[18] However, according to James Hankins, Ficino was misunderstood. In fact, communication between Pletho and Cosimo de' Medici - for whose meeting there is no independent evidence - would have been severely constrained by the language barrier. Furthermore, Ficino's "Platonic Academy" was more of an "informal gymnasium" that did not have a particularly Platonic orientation.[21] Nevertheless, Pletho came to be considered one of the most important influences on the Italian Renaissance. Marsilio Ficino, the Florentine humanist and the first director of the Accademia Platonica, paid Plethon the ultimate honour, calling him 'the second Plato', while Cardinal Bessarion speculated as to whether Plato's soul occupied his body. Plethon may also have been the source for Ficino's Orphic system of natural magic.[12]

While still in Florence, Pletho wrote a volume titled Wherein Aristotle disagrees with Plato, commonly called De Differentiis, to correct the misunderstandings he had encountered. He claimed he had written it "without serious intent" while incapacitated through illness, "to comfort myself and to please those who are dedicated to Plato".[22] George Scholarius responded with a Defence of Aristotle, which elicited Plethon's subsequent Reply. Expatriate Byzantine scholars and later Italian humanists continued the argument.[18]

Pletho died in Mistra in 1452, or in 1454, according to J. Monfasani (the difference between the two dates being significant as to whether or not Plethon still lived to know of the Fall of Constantinople in 1453). In 1466, some of his Italian disciples, headed by Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta, stole his remains from Mistra and interred them in the Tempio Malatestiano in Rimini, "so that the great Teacher may be among free men".

Writings[]

Reform of the Peloponnese[]

Believing that the Peloponnesians were direct descendants of the ancient Hellenes, Plethon rejected Justinian's idea of a universal Empire in favour of recreating the Hellenistic civilization, the zenith of Greek influence.[23] In his 1415 and 1418 pamphlets he urged Manuel II and his son Theodore Palaiologos to turn the peninsula into a cultural island with a new constitution of strongly centralised monarchy advised by a small body of middle-class educated men. The army must be composed only of professional native Greek soldiers, who would be supported by the taxpayers, or "Helots" who would be exempt from military service. Land was to be publicly owned, and a third of all produce given to the state fund; incentives would be given for cultivating virgin land. Trade would be regulated and the use of coinage limited, barter instead being encouraged; locally available products would be supported over imports. Mutilation as a punishment would be abolished, and chain gangs introduced. Homosexuals and sexual deviants would be burnt at the stake. The social and political ideas in these pamphlets were largely derived from Plato's Republic. Plethon touched little on religion, although he expressed disdain for monks, who "render no service to the common good". He vaguely prescribed three religious principles: belief in a supreme being; that this being has concern for mankind; and that it is uninfluenced by gifts or flattery. Manuel and Theodore did not act on any of these reforms.[15]

De Differentiis[]

In De Differentiis Plethon compares Aristotle's and Plato's conceptions of God, arguing that Plato credits God with more exalted powers as "creator of every kind of intelligible and separate substance, and hence of our entire universe", while Aristotle has God as only the motive force of the universe; Plato's God is also the end and final cause of existence, while Aristotle's God is only the end of movement and change.[18] Plethon derides Aristotle for discussing unimportant matters such as shellfish and embryos while failing to credit God with creating the universe,[18] for believing the heavens are composed of a fifth element, and for his view that contemplation was the greatest pleasure; the latter aligned him with Epicurus, Plethon argued, and he attributed this same pleasure-seeking to monks, whom he accused of laziness.[12] Later, in response to Gennadius' Defence of Aristotle, Plethon argued in his Reply that Plato's God was more consistent with Christian doctrine than Aristotle's, and this, according to Darien DeBolt, was probably in part an attempt to escape suspicion of heterodoxy.[18]

Nomoi[]

I myself heard him at Florence ... asserting that in a few more years the whole world would accept one and the same religion with one mind, one intelligence, one teaching. And when I asked him “Christ’s or Muhammad’s?,” he said, “Neither; but it will not differ much from paganism.” I was so shocked by these words that I hated him ever after and feared him like a poisonous viper, and I could no longer bear to see or hear him. I heard, too, from a number of Greeks who escaped here from the Peloponnese that he openly said before he died ... that not many years after his death Muhammad and Christ would collapse and the true truth would shine through every region of the globe.

— George of Trebizond, Comparatio Platonis et Aristotelis, fol. v63[24]

After his death, Plethon's Nómōn syngraphḗ (Νόμων συγγραφή) or Nómoi (Νόμοι, "Book of Laws") was discovered. It came into the possession of Princess Theodora, wife of Demetrios Palaiologos, despot of Morea. Theodora sent the manuscript to Scholarius, now Gennadius II, Patriarch of Constantinople, asking for his advice on what to do with it; he returned it, advising her to destroy it. Morea was under invasion from Sultan Mehmet II, and Theodora escaped with Demetrios to Constantinople where she gave the manuscript back to Gennadius, reluctant to destroy the only copy of such a distinguished scholar's work herself. Gennadius burnt it in 1460; however, in a letter to the Exarch Joseph (which still survives) he details the book, providing chapter headings and brief summaries of the contents.[18] It seemed to represent a merging of Stoic philosophy and Zoroastrian mysticism, and discussed astrology, daemons and the migration of the soul. He recommended religious rites and hymns to petition the classical gods, such as Zeus, whom he saw as universal principles and planetary powers. Man, as relative of the gods, should strive towards good. Plethon believed the universe has no beginning or end in time, and being created perfect, nothing may be added to it. He rejected the concept of a brief reign of evil followed by perpetual happiness, and held that the human soul is reincarnated, directed by the gods into successive bodies to fulfill divine order. This same divine order, he believed, governed the organisation of bees, the foresight of ants and the dexterity of spiders, as well as the growth of plants, magnetic attraction, and the amalgamation of mercury and gold.[12]

Plethon drew up plans in his Nómoi to radically change the structure and philosophy of the Byzantine Empire in line with his interpretation of Platonism. The new state religion was to be founded on a hierarchical pantheon of pagan gods, based largely upon the ideas of humanism prevalent at the time, incorporating themes such as rationalism and logic. As an ad-hoc measure he also supported the reconciliation of the two churches in order to secure Western Europe's support against the Ottomans.[25] He also proposed more practical, immediate measures, such as rebuilding the Hexamilion, the ancient defensive wall across the Isthmus of Corinth, which had been breached by the Ottomans in 1423.

The political and social elements of his theories covered the creation of communities, government (he promoted benevolent monarchy as the most stable form), land ownership (land should be shared, rather than individually owned), social organisation, families, and divisions of sex and class. He believed that labourers should keep a third of their produce, and that soldiers should be professional. He held that love should be private not because it is shameful, but because it is sacred.[12]

Summary[]

Plethon's own summary of the Nómoi also survived, amongst manuscripts held by his former student Bessarion. This summary, titled Summary of the Doctrines of Zoroaster and Plato, affirms the existence of a pantheon of gods, with Zeus as supreme sovereign, containing within himself all being in an undivided state; his eldest child, motherless, is Poseidon, who created the heavens and rules all below, ordaining order in the universe. Zeus' other children include an array of "supercelestial" gods, the Olympians and Tartareans, all motherless. Of these Hera is third in command after Poseidon, creatress and ruler of indestructible matter, and the mother by Zeus of the heavenly gods, demi-gods and spirits. The Olympians rule immortal life in the heavens, the Tartareans mortal life below, their leader Kronos ruling over mortality altogether. The eldest of the heavenly gods is Helios, master of the heavens here and source of all mortal life on earth. The gods are responsible for much good and no evil, and guide all life towards divine order. Plethon describes the creation of the universe as being perfect and outside of time, so that the universe remains eternal, without beginning or end. The soul of man, like the gods is immortal and essentially good, and is reincarnated in successive mortal bodies for eternity at the direction of the gods.[18]

Other works[]

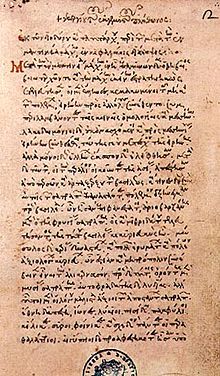

Many of Plethon's other works still exist in manuscript form in various European libraries. Most of Plethon's works can be found in J. P. Migne's Patrologia Graeca collection; for a complete list see Fabricius, Bibliotheca Graeca (ed. Harles), xii.

In modern literature[]

Early in his writing career, E. M. Forster attempted a historical novel about Plethon and Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta, but was not satisfied with the result and never published it ��� though he kept the manuscript and later showed it to Naomi Mitchison.[26]

Ezra Pound included Plethon in his poem The Cantos. References to Plethon and Sigismondo Malatesta can be found in canto 8. Plethon is also mentioned in canto 23 and 26. Pound was fascinated by the role that Plethon's conversation must have had on Cosimo de Medici and his decision to acquire Greek manuscripts of Plato and Neoplatonic philosophers. By having manuscripts brought from Greece and becoming the patron of "the young boy, Ficino," Cosimo facilitated the preservation and transmission of Greek cultural patrimony into the modern world after the fall of Constantinople in 1453. Plethon thus played a key but hidden role in the Italian Renaissance.

Pletho is a major character in the historical novel Porphyry and Ash by Peter Sandham, set in the final year of the Byzantine Empire.

See also[]

- Greek scholars in the Renaissance

- Christian heresy

- Hellenistic religion

- Polytheistic reconstructionism

- Renaissance humanism

- Renaissance magic

Notes[]

References[]

- ^ Niketas Siniossoglou, Radical Platonism in Byzantium: Illumination and Utopia in Gemistos Plethon, Cambridge University Press, 2011, p. 3.

- ^ James Hankins, Humanism and Platonism in the Italian Renaissance, Volume 1, Ed. di Storia e Letteratura, 2003, p. 207.

- ^ Sophia Howlett, Marsilio Ficino and His World, Springer, 2016, p. 42.

- ^ Humphreys, Sarah C.; Wagner, Rudolf G. (2013). Modernity's Classics. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 125. ISBN 978-3-642-33071-1.

- ^ Hanegraaff p.29-31

- ^ Richard Clogg, Woodhouse, Christopher Montague, fifth Baron Terrington (1917–2001), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Jan 2005

- ^ Hanegraaff p.38

- ^ Hanegraaff p.41

- ^ Makrides, (2009) p.136"

- ^ Woodhouse, C.M. (1986)

- ^ Zervas, (2010). p.4

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Merry, Bruce (2002) "George Gemistos Plethon (c. 1355/60–1452)" in Amoia, Alba & Knapp, Bettina L., Multicultural Writers from Antiquity to 1945: A Bio-Bibliographical Sourcebook. Greenwood Publishing Group.

- ^ Hanegraaff p.31

- ^ Πλήθων: "the full", pronounced [ˈpliθon]. Plethon is also an archaic translation of the Greek γεμιστός gemistós ("full, stuffed")

- ^ Jump up to: a b Burns, James Henderson (ed.) (1991). The Cambridge History of Medieval Political Thought C. 350 – C. 1450. Cambridge University Press. pp. 77–8.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- ^ Hanegraaff p.31

- ^ Hanegraaff p.32

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h DeBolt, Darien C. (1998) George Gemistos Plethon on God: Heterodoxy in Defence of Orthodoxy. A paper delivered at the Twentieth World Congress of Philosophy, Boston, Mass. Retrieved 2008-11-20.

- ^ Timaeus in the partial translation of Calcidius was available; Henricus Aristippus' 12th century translation of the Meno and Phaedo was available, but obscure; Leonardo Bruni's translations of the Phaedo, Apology, Crito and Phaedrus appeared only shortly before Pletho's visit. (DeBolt)

- ^ James, Hankins. "Cosimo de' Medici and the 'Platonic Academy'". Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes. 53. ISSN 0075-4390.

- ^ Hanegraaff p.41

- ^ Hanegraaff p.32

- ^ James Henderson Burns, The Cambridge history of medieval political thought c. 350–c. 1450, Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- ^ Hanegraaff, p. 38.

- ^ Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 7, p. 356.

- ^ Mitchison, Naomi (1986) [1979]. "11: Morgan Comes to Tea". You May Well Ask: A Memoir 1920–1940. London: Fontana Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-00-654193-6.

Sources[]

- Benakis, A. G. and Baloglou, Ch. P., Proceedings of the International Congress of Plethon and His Time, Mystras, 26–29 June 2002, Athens-Mystras, 2003 ISBN 960-87144-1-9

- Brown, Alison M., 'Platonism in fifteenth century Florence and its contribution to early modern political thought', Journal of Modern History 58 (1986), 383–413.

- Hanegraaff, Wouter (2012). Esotericism and the Academy: Rejected Knowledge in Western Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521196215.

- Harris, Jonathan, 'The influence of Plethon's idea of fate on the historian Laonikos Chalkokondyles', in: Proceedings of the International Congress on Plethon and his Time, Mystras, 26–29 June 2002, ed. L.G. Benakis and Ch.P. Baloglou (Athens: Society for Peloponnesian and Byzantine Studies, 2004), pp. 211–17

- Keller, A., 'Two Byzantine scholars and their reception in Italy',in: Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 20 (1957), 363–70

- Makrides, Vasilios (2009). Hellenic Temples and Christian Churches: A Concise History of the Religious Cultures of Greece from Antiquity to the Present. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-9568-2.

- Mandilas, Kostas, Georgius Gemistos Plethon (Athens 1997)* ISBN 960-7748-08-5

- Matula, Jozef and Blum, Paul Richard (ed.), Georgios Gemistos Plethon – The Byzantine and the Latin Renaissance (Olomouc 2014) [1]

- Michalopoulos, Dimitris, "George Gemistos Pletho and his Legacy" in Intelectualii Politicii si Politica Intelectuallilor, Editura Cetatea de Scaun, 2016, p. 448-459 (ISBN 978-606-537-347-1)

- Masai, François, Pléthon et le platonisme de Mistra (Paris, 1956)

- Monfasani, John, 'Platonic paganism in the fifteenth century', in: John Monfasani, Byzantine Scholars in Renaissance Italy: Cardinal Bessarion and Other Émigrés, (Aldershot, 1995).

- Runciman, Steven, The Last Byzantine Renaissance (Cambridge, 1970)

- Setton, Kenneth M. 'The Byzantine background to the Italian Renaissance', in: Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 100 (1956), 1–76.

- Tambrun, Brigitte. Pléthon. Le retour de Platon, Paris, Vrin, 2006 ISBN 2-7116-1859-5

- Tambrun-Krasker, Brigitte, Georges Gémiste Pléthon, Traité des vertus. Édition critique avec introduction, traduction et commentaire, Corpus Philosophorum Medii Aevi, Philosophi Byzantini 3, Athens-The Academy of Athens, E. J. Brill, Leiden, 1987.

- Tambrun-Krasker, Brigitte, Magika logia tôn apo Zoroastrou magôn, Georgiou Gemistou Plêthônos Exêgêsis eis ta auta logia. Oracles chaldaïques. Recension de Georges Gémiste Pléthon. Edition critique avec introduction, traduction et commentaire par Brigitte Tambrun-Krasker. La recension arabe des Magika logia par Michel Tardieu, Corpus Philosophorum Medii Aevi, Philosophi Byzantini 7, Athens-The Academy of Athens, Paris, Librairie J. Vrin, Bruxelles, éditions Ousia, 1995, LXXX+187 p.

- Tambrun, Brigitte, "Pletho" (article) in: W.J. Hanegraaff, A. Faivre, R. van den Broek, J.-P. Brach ed., Dictionary of Gnosis and Western Esotericism, Leiden, E.J. Brill, 2005, 2006.

- Vassileiou, Fotis & Saribalidou, Barbara, Short Biographical Lexicon of Byzantine Academics Immigrants in Western Europe, 2007.

- Viglas, Katelis, 'Alexandre Joseph Hidulphe Vincent on George Gemistos Plethon', Anistoriton Journal, Vol. 13, No 1, 2012–2013, 1–12

- Vojtech Hladky, The Philosophy of Gemistos Plethon. Platonism in Late Byzantium, between Hellenism and Orthodoxy, Ashgate, Farnham-Burlington, 2014 ISBN 978-1-4094-5294-2

- Woodhouse, Cristopher Montague, George Gemistos Plethon – The Last of the Hellenes (Oxford, 1986).

- Zervas, Theodore. (2010). Beginnings of a Modern Greek Identity: Byzantine Legacy.

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Gemistus Pletho, Georgius". Encyclopædia Britannica. 11 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 573.

External links[]

- Gemistus Pletho at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- Pléthon (1858), Traité des lois (Book of Laws) at archive.org

- Works by or about Gemistus Pletho in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Plethon at the New Acropolis library

- "George Gemistos Plethon on God: Heterodoxy in Defense of Orthodoxy"

- http://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00293398/fr/

- http://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00293417/fr/

- Byzantine philosophers

- Constantinopolitan Greeks

- Greek Renaissance humanists

- Neoplatonists

- Christianity and Hellenistic philosophy

- People of the Despotate of the Morea

- 14th-century Byzantine people

- 15th-century Byzantine people

- 14th-century Greek people

- 15th-century Greek people

- Late-Roman-era pagans

- 14th-century Greek writers

- 15th-century Greek writers

- 15th-century Greek educators

- 14th-century Greek educators

- 14th-century Greek scientists

- 15th-century Greek scientists

- 14th-century Greek philosophers

- 15th-century Greek philosophers

- 14th-century Greek mathematicians

- 15th-century Greek mathematicians

- 14th-century Greek astronomers

- 15th-century Greek astronomers