Gerard John Schaefer

Gerard John Schaefer | |

|---|---|

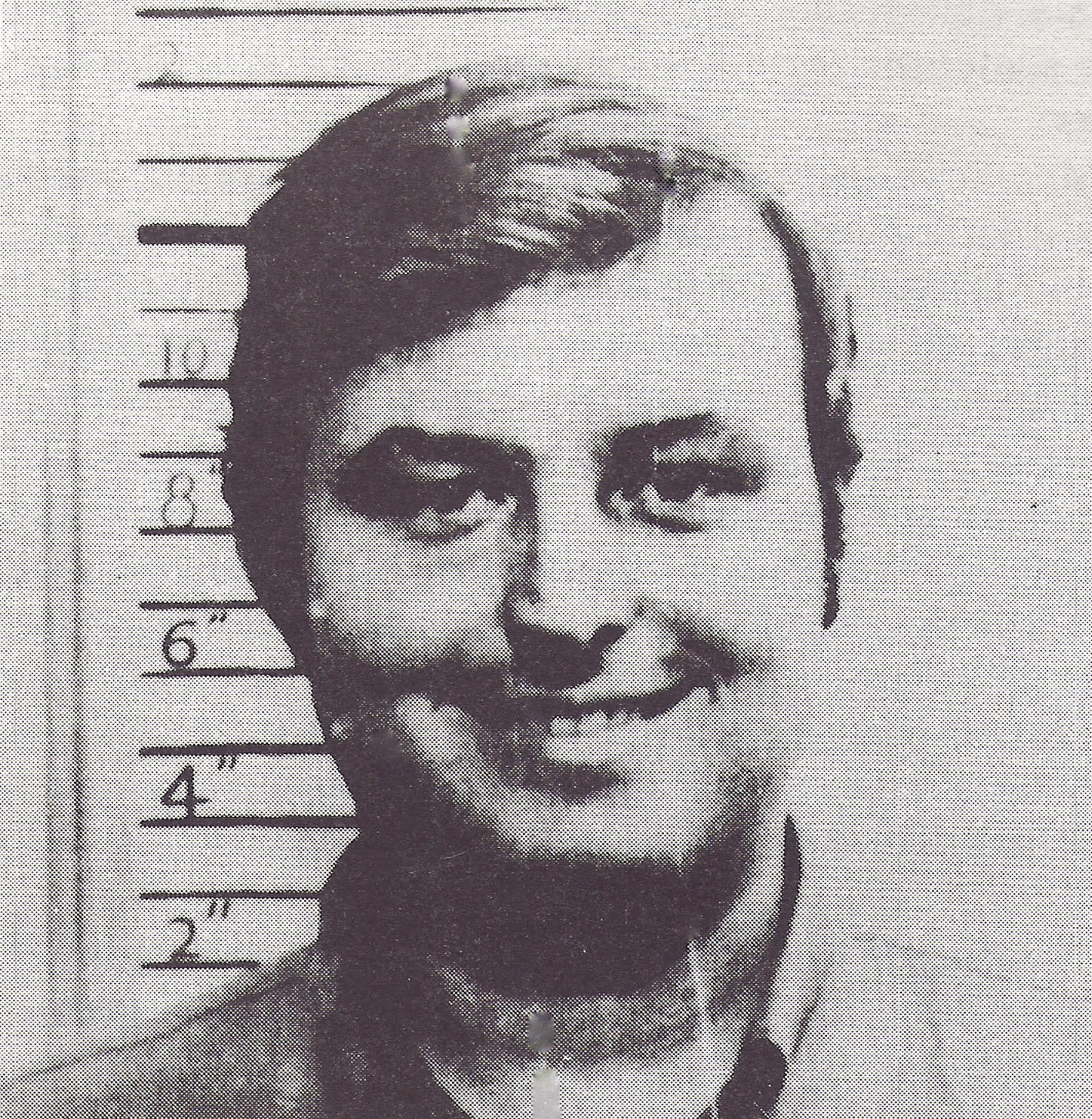

Schaefer c. 1973 | |

| Born | Gerard John Schaefer Jr. March 26, 1946 Wisconsin, U.S. |

| Died | December 3, 1995 (aged 49) Bradford County, Florida, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Multiple stab wounds |

| Other names | Jerry Shepherd |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Conviction(s) | Murder |

| Criminal penalty | Life imprisonment |

| Details | |

| Victims | 2–30+ |

Span of crimes | 1966–1973 |

| Country | United States |

| State(s) | Florida |

Date apprehended | April 7, 1973 |

| Imprisoned at | Florida State Prison |

Gerard John Schaefer Jr. (March 26, 1946 – December 3, 1995) was an American murderer and suspected serial killer who was imprisoned in 1973 for murders he committed while he was a sheriff's deputy in Martin County, Florida. Schaefer was convicted of two murders, but was suspected of many others. He frequently appealed against his conviction, but privately boasted, both verbally and in writing, of killing more than thirty women and girls. In December 1995, Schaefer was stabbed to death in his prison cell.

Early life[]

Gerard Schaefer was the first of three children born to Catholic parents, Gerard and Doris Marie (née Runcie) Schaefer. He was born in Wisconsin and was raised in Atlanta, Georgia, where he attended Marist Academy until 1960 when his family moved to Fort Lauderdale, Florida. Schaefer did not get along well with his father, who he believed favored his sister.[1]

In his teens, he began an obsession with women's underwear and became a peeping tom, spying on a neighbor girl named Leigh Hainline, of whose subsequent murder he is suspected. Schaefer would later admit to killing animals in his youth and cross dressing, although at other times he claimed the latter was solely part of his successful attempt to avoid the draft during the Vietnam War.[2]

After graduating from St. Thomas Aquinas High School in 1964,[3] Schaefer went to college at Florida Atlantic University, and got married during that time. In 1969, he became a teacher at Plantation High School, but was soon fired for "totally inappropriate behavior", according to the principal.[4] After being turned down from the priesthood, Schaefer turned to law enforcement as a career, graduating as a patrolman at the end of 1971 at age 25.

Arrest[]

On July 21, 1972, Schaefer picked up two teenage girls named Nancy Trotter and Paula Sue Wells, who were hitchhiking, while he was on patrol. The following day, he abducted them, took them to a remote forest and tied them to trees where he threatened to kill them or sell them into prostitution. However, Schaefer was called away on his police radio, leaving the girls tied up. He vowed that he would return.[citation needed]

Trotter and Wells, who were aged 17 and 18, escaped their bonds and went to the nearest police station, which was actually their kidnapper's own station. When Schaefer returned to the woods and found his victims gone, he called his station and claimed that he had done "something foolish", explaining that he had pretended to kidnap and threaten to kill two hitchhikers in order to scare them into avoiding such an irresponsible method of travel. Schaefer's boss did not believe him and he ordered Schaefer to the station, where he was stripped of his badge and charged with false imprisonment and assault.[citation needed]

After posting bail, Schaefer was released. Two months later, on September 27, 1972, Schaefer abducted, tortured, and murdered Susan Place, aged 17, and Georgia Jessup, 16, and buried them in Oak Hammock Park in Port Saint Lucie, Florida. In December 1972, Schaefer appeared in court in relation to the July abductions. Due to a plea bargain, he was able to plead guilty to just one charge of aggravated assault, for which he received a sentence of one year.[citation needed]

Murder conviction[]

In April 1973, over six months after they vanished, the decomposing, mutilated remains of Place and Jessup were found. The girls had been tied to a tree at some point and had vanished while hitchhiking. These similarities to Schaefer's treatment of the girls who had escaped led the police to obtain a search warrant for the house he and his wife shared with Schaefer's mother.[citation needed]

In Schaefer's bedroom, the police found lurid stories he had written that were full of descriptions of the torture, rape, and murder of women, whom he routinely referred to as "whores" and "sluts". More damningly, the authorities found personal possessions such as jewelry, diaries, and in one case, teeth from at least eight young women and girls who had gone missing in recent years. Some of the jewelry was from Leigh Hainline Bonadies, Schaefer's neighbor from when they were teenagers.[5]

Bonadies had vanished in 1969 in Fort Lauderdale, after leaving a note for her husband saying she was making a short trip to Miami. Schaefer was never charged in connection with her case. Her skull, which was found to have multiple bullet holes, was discovered at a construction site in Palm Beach County in April 1978 and identified one month later.[6]

Also among the items was a purse identified as belonging to Place. Place's mother later identified Schaefer as being the man she last saw with her daughter and Jessup. Schaefer was charged with the murders of Place and Jessup. In October 1973, he was found guilty and given two life sentences. Authorities soon stated that he was linked to around 30 missing women and girls.

Place and Jessup may not have been Schaefer's final victims; two 14-year-old girls named Mary Briscolina and Elsie Farmer vanished while hitchhiking on October 23, 1972, just a few weeks after Place and Jessup were killed.[7] Their bodies were later recovered, and jewelry belonging to one of the girls was later found in Schaefer's home. Two 19-year-old hitchhikers, Collete Goodenough and Barbara Ann Wilcox, disappeared in January 1973. Personal property belonging to both women was later recovered from Schaefer's home, although their bodies were not discovered until 1977.

Imprisonment and death[]

This section does not cite any sources. (September 2020) |

Schaefer appealed his conviction, claiming at one point that he had been framed. All his appeals were rejected. Schaefer later began filing frivolous lawsuits; he sued true crime writer, Patrick Kendrick, for describing him as "an overweight, doughy, middle aged man who preyed on victims who were psychologically and physiologically weaker than him". Schaefer also sued authors Sondra London, Colin Wilson and Michael Newton and former FBI agent Robert Ressler for describing him as a serial killer.

In support of her defense against the lawsuit, London compiled an exhibit of photocopies of five hundred incriminating pages of his handwritten correspondence. The judge dismissed Schaefer's lawsuit without further ado. After London provided copies of the five hundred page exhibit to Newton and Wilson, Schaefer's lawsuits against them were also dismissed. Kendrick's suit was still ongoing until Schaefer's own murder in prison.

Until his death, Schaefer continued to threaten Sondra London. He also wrote threatening letters to Patrick Kendrick suggesting he had willing agents who would do his bidding and that he "would hate to see something happen to your [Kendrick's] family". Kendrick went on to write fiction novels often describing brutal murders, which he relates to his experience with Schaefer.

On December 3, 1995, Schaefer was found stabbed to death in his cell. According to prison officials and prosecutors, fellow inmate Vincent Rivera killed Schaefer in an argument over a cup of coffee. In 1999, Rivera was convicted of killing Schaefer and had 53 years and ten months added to the life-plus-twenty years sentence he was already serving for double murder.

After attending Rivera's murder trial and speaking to Rivera, Sondra London declared this version of events implausible noting several little-known facts: a full-palm print in blood was found on the wall of Schaefer's cell. When lab results failed to match it to either Schaefer or Rivera, the evidence was thrown out instead of being presented to the jury. Schaefer's body was found covered with boot prints, and expert testimony at Rivera's trial established that the patterns of the prints matched those of boots issued to correctional officers. It was further established that no inmates were allowed to wear those particular boots.

Rivera never confessed to confess to the crime nor gave a motive although he did reveal highly relevant circumstances in correspondence he sent to Sondra London; to wit, Rivera had been an ear-witness to the prison murder of Frank Valdes by corrections officers. Rivera had written a complaint about the first assault on Valdes and was still held in the cell next to Valdes when the second beating killed him. Rivera was actively resisting the cover-up claiming Valdes had killed himself, filing multiple grievances and appeals, when he was accused of killing Schaefer.

Sondra London later stated that she believed Schaefer was likely killed for informing on other inmates. Schaefer made multiple statements to London to the effect that he used his status as a "death row law clerk" to get confidential information from inmates. In an effort to curry favor with authorities, Schaefer then gave the information to the prosecutor's office. The information was then used against the inmates at their trials. In the year before Schaefer's death, other inmates repeatedly threw human waste at him and his cell was set on fire twice. Schaefer's classification officer told London Schaefer's was killed after he leaked information to authorities about an inmate who was well respected behind bars.

Schaefer's sister Sara told reporters that she believed Schaefer's murder was a cover-up related to his attempts to verify the confession and subsequent retraction of Ottis Toole to the killing of Adam Walsh.

At the time of Schaefer's death, Broward County homicide detective John King and homicide chief Tim Bronson were preparing to bring charges against Schaefer for three more unsolved murders to ensure he would never get out of prison.

Alleged victims[]

- Nancy Leichner (21) and Pamela Ann Nater (20). Both young women disappeared October 2, 1966.[8][9]

- Leigh Hainline Bonadies (25). Disappeared September 8, 1969.[10]

- Carmen Marie Hallock (22). Disappeared December 18, 1969.

- Peggy Rahn (9) and Wendy Stevenson (8). Both children disappeared on December 29, 1969. Schaefer sent a letter to his girlfriend in which he confessed to killing them. Their bodies have never been found.

- Belinda Hutchens (22). A cocktail waitress with a 2-year-old daughter. She had a history of arrests for prostitution. Last seen entering a blue Datsun on January 4, 1972. Hutchens was known to have dated Schaefer while he was attending the police academy. During the 1973 search of Schaefer's home, police recovered an address-book later identified as belonging to Belinda by her husband.[11]

- Debora Sue Lowe (13). Disappeared February 29, 1972. Lowe's family believe Schaefer was involved in her disappearance, and Lowe was known to Schaefer.[12]

- Mary Briscolina (14) and Elsie Farmer (14). Both vanished while hitchhiking on October 23, 1972

- Collette Goodenough (19) and Barbara Wilcox (19). Both disappeared January 8, 1973.[13]

Killer Fiction[]

Sondra London, a true crime writer who had been Schaefer's girlfriend in high school, interviewed him at length following his conviction, and published a compilation of his short stories and drawings entitled Killer Fiction in 1990. A second book, Beyond Killer Fiction, followed two years later. Schaefer's stories typically involved savage, graphic torture and murder of women, usually from the perspective of the killer, who was often a rogue police officer.[14] A revised edition of Killer Fiction, released after Schaefer's death, included stories and rambling articles from the first two books and a collection of letters to London, in which Schaefer confessed to killing 34 women and girls, and bragged that he had impressed fellow inmate Ted Bundy.[15]

London noted that at the time Schaefer was corresponding with her, he was publicly proclaiming his innocence and threatening to sue anyone who labeled him a serial killer. In one letter, Schaefer wrote that he began murdering women in 1965, when he was 19. In another, he boasted of killing and cannibalizing two schoolgirls, nine-year-old Peggy Rahn and eight-year-old Wendy Stevenson, who vanished in December 1969.[16][17] Publicly, Schaefer had denied any involvement.[18]:82–90

London ended her collaboration with Schaefer in 1991, after repudiating his story that he was merely a "framed ex-cop" who wrote lurid fiction. When she stated that he was indeed every bit the serial killer he simultaneously boasted of being, Schaefer allegedly repeatedly threatened her life and filed suit against her for calling him a serial killer in print.[18]:142

See also[]

Further reading and films[]

- Howard, Justice TERRIBLE THINGS TERRIBLE THINGS -Book on GJ Schaefer

- , AKA Petrified, An Original Screenplay (2014) & ANOMALY: Devil's Night at the Devil's Tree, A Paranormal Investigation Harbinger Press (2013), p. 136.

- The Devil Tree: The Legend Of Port Saint Lucie Pennsylvania: Sunbury Press (2015), p. 192. ISBN 978-1620065884

- Ressler, Robert K. and Schachtman, Tom Whoever Fights Monsters: My Twenty Years Hunting Serial Killers for the FBI. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1992, pp. 122–127. ISBN 0-312-07883-8

- The Devil Tree Uncovered Investigation Documentary produced by Nicole K. Rankin

References[]

- ^ Cole, Catherine; Young, Cynthia (2011). "The Cop Killer". True Crime: Florida: The State's Most Notorious Criminal Cases. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-8117-4439-3.

- ^ Cole, Catherine; Young, Cynthia (2011). "The Cop Killer". True Crime: Florida: The State's Most Notorious Criminal Cases. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-8117-4439-3.

- ^ Cole, Catherine; Young, Cynthia (2011). "The Cop Killer". True Crime: Florida: The State's Most Notorious Criminal Cases. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-8117-4439-3.

- ^ Parker, RJ (2014). "Protect and Serve: Gerard John Schaefer". In Hartwell, Deb (ed.). Serial Killer Groupies. pp. 136–37. ISBN 978-1-5025-4090-4.

- ^ "Lakeland Ledger". Retrieved September 13, 2016.

- ^ "Lakeland Ledger". Retrieved September 13, 2016.

- ^ "Gerard Schaefer". Murderers Database (United Kingdom). Archived from the original on July 10, 2010. Retrieved September 3, 2009.

- ^ "Pamela Ann Nater". The Doe Network. Retrieved April 28, 2012.

- ^ "Nancy Leichner". The Doe Network. Retrieved April 28, 2012.

- ^ Doe network

- ^ "The Devil Tree, Port Saint Lucie: The Killing Ground of Serial Killer Gerard Schaefer". miamighostchronicles.com.

- ^ "Debora Sue Lowe". The Charley Project. Archived from the original on June 13, 2018. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- ^ "The Killing Ground of Serial Killer Gerard Schaefer". Retrieved August 24, 2020.

- ^ Bourgoin, Stéphane (2015). Sex Beast : Sur la trace du pire tueur en série de tous les temps [Sex Beast: On the Trail of the Worst Serial Killer of All Time] (in French). Paris: Grasset. p. 95. ISBN 978-2-246-85511-8.

- ^ Gerard John Schaefer's Art. Serial Killer Art and Kitsch. Archived May 30, 2015, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved May 29, 2015.

- ^ "Peggy Rahn". The Doe Network. March 17, 2017. 2241DFFL.

- ^ "Wendy Brown Stevenson". The Doe Network. March 17, 2017. 2242DFFL.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Schaefer, G.J. (2011). London, Sondra (ed.). Killer Fiction. Vancouver, Washington: Feral House. ISBN 978-1-936239-19-1.

External links[]

- 1946 births

- 1969 crimes in the United States

- 1972 murders in the United States

- 1995 deaths

- 1995 murders in the United States

- 20th-century American criminals

- American deputy sheriffs

- American male criminals

- American murder victims

- American murderers of children

- American people convicted of murder

- American people who died in prison custody

- American police officers

- American police officers convicted of crimes

- American police officers convicted of murder

- American prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment

- American rapists

- American serial killers

- Crime in Florida

- Criminals from Florida

- Criminals from Georgia (U.S. state)

- Criminals from Wisconsin

- Deaths by stabbing in the United States

- Incidents of violence against girls

- Male murder victims

- Male serial killers

- People convicted of murder by Florida

- People from Atlanta

- People from Fort Lauderdale, Florida

- People from Wisconsin

- People murdered in Florida

- Prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment by Florida

- Prisoners who died in Florida detention

- Serial killers murdered in prison custody

- Suspected serial killers

- Torture in the United States

- Violence against women in the United States