German retribution against Poles who helped Jews

German retribution against Poles who helped Jews were repressive measures taken by the German occupation authorities against non-Jewish Polish citizens who helped Jews persecuted by Nazi Germany during the Holocaust in Poland, 1939 to 1945.

The orders of the occupation authorities, and in particular the ordinance of the general governor Hans Frank of October 15, 1941, provided for the death penalty for every Pole who would provide shelter for a Jew or help him in any other way. In practice, the range of penalties applied to those helping Jews was wide, including fines, confiscation of property, beatings, imprisonment, deportation to Nazi concentration camps and the death penalty. Due to the principle of collective responsibility applied by the Germans, families of those who helped Jews and sometimes entire local communities were subjects to retribution. The exact number of Poles executed by the Germans for helping Jews has not yet been precisely determined. The most cautious estimates give the number of around a few hundred people executed, and the high-end estimates, several thousand.

German anti-Jewish policy in occupied Poland

In the first years of the Second World War, German policy in relation to the "Jewish question" in occupied Poland was not coherent and consistent.[1] Nevertheless, its fundamental aim was to isolate Jews, loot their property, exploit them through forced labour[1][2] and, in the final stage, remove them completely from the land under the authority of the Third Reich.[2] An initial plan for dealing with the Jewish population in Poland was adopted already on September 21, 1939, i. e. before the end of the September campaign.[3] On that day, a meeting was held in Berlin led by SS-Gruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich, attended by the chief heads of the main departments of the and commander of Einsatzgruppen operating in Poland.[4] It was then established that all Jews living in the lands, which were to be incorporated into the Reich, would be resettled in central Poland. Mass deportations were to be preceded by removal of the Jewish population from rural areas and its concentration in larger urban centers.[4] In the remaining occupied areas, it was also intended to forcibly resettle Jews to larger towns, especially to those located near railway lines.[4] Moreover, during the meeting, a number of recommendations were adopted, including the creation of "Jewish Elder Councils", the establishment of a census of the Jewish population, as well as its marking and taking up forced labor.[3]

The need to isolate Jews from the rest of the inhabitants of occupied Poland was emphasized by the Memorial on the treatment of people in former Polish territories from a racial and political point of view, drawn up in November 1939 by the NSDAP Office of Racial Policy. Among other things, its authors wrote that "the task of the German administration will be to differentiate and win Poles and Jews against each other".[3] Recommendations concerning the fuelling of antagonisms between Poles and Jews and other national minorities are also included in the Memorial on the legal position of German policy towards Poles from a national and political point of view, prepared in January 1940 for the Academy of German Law.[5][3]

From the first days of the occupation, the Germans treated the Jewish population in the spirit of the racist Nuremberg laws.[3] From September 1939, the occupying authorities at various levels issued orders ordering Jews to wear special bands or identification marks, as well as to mark their apartments and businesses.[3] On the territory of the General Government, this policy was sanctioned by the ordinance of Governor General Hans Frank of 23 November 1939, which required all Jews over ten years of age to wear Star of David armbands.[3] The marking of Jews was also introduced on the territories incorporated into the Reich, but this was usually done on the basis of secret instructions, since the relevant law was introduced in Germany only in the autumn of 1941.[3] Moreover, in the first months of the occupation almost all towns of the General Government and the Warta Country introduced far-reaching restrictions on the freedom of movement of Jews. To this end, measures such as curfew, a ban on leaving the place of residence and a ban on using different means of transport were used.[3] According to a decree by Hans Frank of 26 January 1940, Jews were prohibited from travelling by train.[3][1] Over time, this ban has been extended to other means of transport.[1] Strict criminal sanctions, up to and including capital punishment, were imposed on those who would violate these provisions.[3]

Germans also took actions aimed at the pauperization of Jews and their exclusion from the economic life of the occupied country.[3] Industrial, trade and service enterprises owned by Jews were confiscated in large numbers. Extensive restrictions have also been introduced in the areas of handicraft production, small-scale trade, property management and money transfer.[3][1] The legally sanctioned "aryanization" of Jewish property was accompanied by individual ("wild") looting.[3] Contributions and special taxes were also imposed on Jews.[3] Representatives of the Jewish intelligentsia were deprived of the right to pursue liberal professions and were dismissed from work in public institutions.[6][3] The decree issued by Hans Frank on October 26, 1939 included forced labor for the Jewish population in the General Government.[3] Two years later, forced labor for Jews was introduced in the territories incorporated into the Reich, however, only by sanctioning the state of matters that had existed there since the first months of the occupation.[3]

The next stage of the anti-Semitic policy of the occupier was ghettoisation of the Jewish population, officially justified by economic, sanitary or political reasons.[3] As an excuse to isolate Jews in closed districts, among other things, Germans used the "" of March 1940, arranged from German inspiration by Polish extreme nationalists.[7] The first Jewish ghetto was established in October 1939 in Piotrków Trybunalski.[3] Over the next few months several more ghettos were created in the General Government and Warta Country, including the ghetto in Łódź (February 1940).[3] Beginning in September 1940, the ghettoisation process became more organized.[3] In October of this same year, it was decided to establish a "Jewish quarter in Warsaw".[3] In March 1941 the ghettos in Kraków and Lublin were established.[3] The process of ghettoisation in the of the General Government was rather at the latest in December 1941.[1] After the outbreak of the German-Soviet War, the organizing of ghettos on Polish lands previously annexed by the USSR[3] took place. The creation of closed Jewish communities was accompanied by a progressive reduction in the number of smaller ghettos.[3] The concentration and isolation of the Jewish population was also to be served by an unrealized project of creating a great "reservation" for Jews in the Lublin region.[3]

The persecution of the Jewish population was accompanied by a large-scale anti-Semitic propaganda campaign aimed at the "Aryan" population – first of all at Poles.[8][6] Using the , cinema or poster, the occupying forces tried to deepen anti-Semitic attitudes and stereotypes, which were already widespread in some parts of Polish society before the war.[6][9] The German propaganda attempted, among other things, to blame Jews for the outbreak of the war and the occupational shortages, as well as to dehumanize them in the eyes of Polish society, e. g. through accusations of spreading infectious diseases (e. g. poster "Jews – lice – typhoid typhus").[2][8][9][3] After the beginning of the war with the USSR and the discovery of the Katyn graves, the slogan of "Judeo-Communism" was also intensively used.[9] In many cases, anti-Semitic propaganda has found its way into fertile soil and influenced Poles' attitudes towards Jews,[9][6] even after the "final solution" was initiated.[8]

After the invasion of the USSR started (June 22, 1941), the anti-Jewish policy of the invader was violently radicalised. East of the , German Einsatzgruppen started its operations, which by the end of 1941 killed from 500 thousand[6] to one million[10] Polish and Soviet Jews. In December 1941, extermination of Jews from the Warta Country began in the extermination camp in Chełmno nad Nerem.[3] By the summer of 1942, all the ghettos in that region had ceased to exist, except for Łódź ghetto.[3] On the other hand, during the night of 16 to 17 March 1942, deportations of the inhabitants of the ghetto in Lublin began to the death camp in Bełżec.[2] The closing of the Lublin Ghetto initiated the mass and systematic extermination of Polish Jews living in the areas of the General Government and Białystok district, which the Germans later baptized with the cryptonym "Aktion Reinhardt".[2] Moreover, starting from mid-1942 the extermination camps created by the Germans on occupied Polish lands became a place of execution of Jews deported from other European countries.[2][3] By November 1943, "Action Reinhardt" had claimed nearly 2 million victims.[2] Although in the second half of the year the extermination camps organized for this operation were closed down, the mass extermination of Polish and European Jews was continued, mainly in the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp.[10][6] In August 1944, the liquidation of the last ghetto in the occupied Polish lands – the Łódź Ghetto took place.[3] As a consequence of the German policy of extermination on occupied Polish lands, the majority of about 5.5 million Holocaust victims, including at least 2.8 million Polish Jews, were murdered.[11]

Retribution against Poles helping Jews

Criminal penalties for helping Jews

In 1941, the rapid spread of infectious diseases in overpopulated ghettos and the general radicalisation of German anti-Jewish policy resulted in tightening of the isolation restrictions imposed on Polish Jews.[1][2] While the Second Restriction of Residence in the General Government on April 29, 1941 provided for prison sentences and fines for non-compliance with the "residence restrictions" regulations, since the middle of that year Jews captured outside the ghetto were usually executed on the spot – usually based on an alleged "attempt to escape".[1] The third regulation on the restriction of residency in the General Government of October 15, 1941 provided for the death penalty for all Jews who "leave their designated district without authorisation", but its sentencing would be the responsibility of the German Special Courts.[1][12] Finally, in November 1941, the German police authorities issued the so-called Schießbefehl order, which authorised police officers to shoot all Jews who were outside the ghetto (including women and children).[1] After the start of "Aktion Reinhardt" the German gendarmerie supported by collaborative police forces systematically tracked, captured and murdered refugees from ghettos, transports and camps. This stage of the Holocaust, called Judenjagd by the Germans (the "hunt for Jews"), lasted until the last days of the occupation.[13]

Historians estimate that in occupied Poland from 100 thousand[2] to 300 thousand[13] Jews attempted to hide "on the Aryan side". The Germans undertook a number of actions aimed at discouraging Poles from providing any kind of assistance to the Jews. In order to achieve this goal, the occupation authorities skillfully managed to administer rewards and penalties.[2][9] On one hand, the "Aryan" population was encouraged to denounce and track Jews in return for money or other goods. In Warsaw, denunciators were rewarded with 500 zlotys and officers of the "blue police" were promised to receive 1/3 of his cash for capturing a Jew hiding "on the Aryan side". In the rural areas of the , a prize in the form of 1 metre of grain was awarded. The award for the denunciation could also include several kilograms of sugar, a litre of spirit, a small quantity of wood or food or clothes belonging to the victim. It is known that in the vicinity of Ostrołęka rewards for denunciators amounted to 3 kilograms of sugar, in Western Małopolska – 500 PLN and 1 kilogram of sugar, in Kraśnik County – from 2 to 5 kg of sugar, in Konin County – property of the victims and 0.5 kg of sugar, in the vicinity of Sandomierz – litre of spirit and 0.5 kg of sugar, in Volhynia – three litres of vodka.[1] These techniques did not go without results. In the Polish society there were individuals who, motivated by profit or anti-Semitism, were actively pursuing and then handing over, robbing or blackmailing Jews who were hiding.[1][6][14] In Warsaw, the number of "szmalcownik people", blackmailers and denunciators, often associated in well-organized gangs, was calculated at 3-4 thousand.[15] In rural areas there were gangs - usually made up of criminals, members of the social margin and declared anti-Semites[1] - who tracked the fugitives and then gave them away to Germans or robbed them on their own, often committing murders and rape.[1][14][2]

The Germans used Polish Blue Police officers to participate in roundups and Judenjagd (search operations). Some police officers attended to these duties zealously, including participating directly in the murder of Jewish escapees.[1] Polish foresters, members of voluntary fire brigades and members of rural guards also took part in the activities. Moreover, Polish village heads, mayors and civil servants were obliged to enforce German regulations concerning the capture of Jews and preventing them from receiving aid.[2]

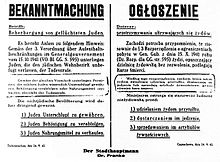

At the same time, the occupation authorities imposed draconian penalties for hiding Jews or providing them with any assistance.[2][6] According to Sebastian Piątkowski and Jacek A. Młynarczyk, "a milestone on the road to complete isolation of the Jewish community from the rest of the conquered population" was signing by Hans Frank of the aforementioned Third Ordinance on Restrictions on residence in the General Government (October 15, 1941). This was the first legal act providing for the death penalty for Poles who "knowingly give shelter" to Jews residing outside the ghetto without permission.[1] This document also announced that "instigators and helpers are subject to the same punishment as the offender, the attempted act will be punished as a committed act", but stated that in lighter cases a prison sentence may be imposed. The aim of the regulation was clear – discourage Jews from seeking rescue outside the ghetto and discourage Polish people from helping them.[16]

Soon afterward, orders with similar content were issued in all districts of the General Government, signed by local governors or SS and police leaders. In many cases, similar orders and announcements were also published by the lower administrative authorities. The announcement issued on November 10, 1941 by the governor of the Warsaw district, Dr Ludwig Fischer, was even more restrictive than Frank's regulation, as it provided for the death penalty to every Pole who "consciously grants shelter or otherwise helps the hiding Jews by providing accommodation (e. g. overnight accommodation, subsistence, by taking them to vehicles of all kinds".[12][15]

After the launch of "Aktion Reinhardt" Jews escaped from the liquidated ghettos or from transports to death camps. This led the German authorities to issue another series of orders reminding the Polish population of the death penalty for trying to help Jewish refugees.[17] In this context, one can mention, among others, the announcement of SS Commander and Police Commander of the Warsaw district SS-Oberführer Ferdinand von Sammern-Frankenegg of 5 September 1942 and the announcement of the district chief administrative officer of Przemyśl County Dr Heinischa of July 27, 1942, police decree of the Starosta of Sanok County, Dr Class of 14 September 1942, announcement of the City Starosta in Częstochowa E. Franke of September 24, 1942,[12] order of the Starosta of the Kraśnik County of October 23, 1942,[14] and the announcement of the Starosta of the Dębica County Schlüter of November 19, 1942. On September 21, 1942, SS-Standartenführer , SS and Police Leader of the , issued a circular to the local administrative and police authorities, which contained the following provisions:[1][12]

The experience of recent weeks has shown that the Jews, in order to avoid evacuation, are fleeing from small Jewish housing districts in the communes. These Jews were certainly received by the Poles. I would ask all mayors to make it clear as soon as possible that every Pole who receives a Jew becomes guilty according to the Third Order on Restrictions on Residence in the General Government of 15 October 1941 ("Dz. Rozp. GG", p. 595).[18] Their helpers are also considered to be those Poles who, although they do not give shelter to the fugitive Jews, still give them provender or sell them food. In all cases, these Poles are liable to the death penalty.

On October 28, 1942, the Supreme Commander of SS and the Police in the General Government SS-Obergruppenführer Friedrich Wilhelm Krüger (HSSPF "Ost") issued a regulation on the creation of so-called remnant ghettos in selected cities of Lublin and Warsaw districts.[16] On November 10, 1942, a similar decree was issued for the districts of Kraków, Radom and Galicia.[19] In § 3 of these regulations, the threat of the death penalty is repeated for people providing shelter or food to Jews who hide outside the designated housing districts. At the same time, unspecified police sanctions (sicherheitspolizeiliche Maßnahmen) were announced against people who do not inform the occupation authorities about the known fact of Jewish presence outside the ghetto (in practice, this meant deportation to a concentration camp). At the end of 1942, a similar decree for the Białystok district was announced by gauleiter of East Prussia Erich Koch. Strict penalties for helping Jews were also imposed in the Warta Country.

Enforcement of German ordinances

According to the provisions of the Third Ordinance on Restrictions on Residence in the General Government and lower-ranking acts, the death penalty was aimed at both Poles who provided shelter to Jews,[20] as well as those who offered money, food, water, or clothing to escapees, provided medical assistance, provided transport or transferred correspondence prepared by the Jew.[12][21] The highest penalties were imposed on people who helped Jews for altruistic reasons, as well as those who helped Jews for compensation or who were involved in commercial transactions with them. As a result of the invader's principle of collective responsibility, the families of carers and sometimes even entire local communities were threatened with retribution. Moreover, in the occupied Polish lands, the Germans created a system of blackmail and dependence system, obliging Poles, under the threat of the most severe punishments, to report every case of hiding Jewish fugitives to the occupation authorities. In particular, Poles holding positions at the lowest levels of administration (village heads, commune heads, officials).[2][8]

In practice, the regulations prohibiting aid to Jewish refugees have not always been enforced with the same severity.[2][15][22] The “2014 Record of the facts of repression against Polish citizens for the help of the Jewish population during World War II” indicates that those accused of supporting Jews were also punished with punishments such as beatings, imprisonment, exile for forced labor, deportation to a concentration camp, confiscation of property, or fines.[23] Sebastian Piątkowski, relying on preserved documents of the special court in Radom, pointed out that especially in the case of small and disposable forms of assistance – such as providing food, clothing or money to the escapees, indicating the way, accepting correspondence – the punishment could be limited to imprisonment or exile to a concentration camp.[24] However, there are also numerous cases where the detection of the fugitive resulted in the execution of the whole Polish family, who took him under their roof, and the robbery and burning of her belongings.

The Frank's decree of October 15, 1941 stipulated that cases concerning the cases of aid to Jewish refugees would be dealt with by German special courts. Until 2014, historians were able to identify 73 Polish citizens, against whom special courts of the General Government conducted cases in this respect. Many times, however, the Germans refused to carry out even simplified court proceedings, and the Jews captured together with their Polish caregivers were murdered on the spot or at the nearest police station or military police station.[1][16] Such a course of action was sanctioned, among other things, by a secret order of the SS Commander and the Police for the Radom district, ordering the extermination of captured Jews and their Polish caregivers on the spot, as well as the burning of buildings where Jews were hidden. At the same time, the Germans took care to give proper publicity to their retribution, so as to intimidate the Polish population and discourage it from providing any aid to Jews. For this purpose, the victims' burials were prohibited in cemeteries, instead, they were buried on the scene of the crime, on nearby fields or in road trenches.[8]

Historians point out that Polish blackmailers and denunciators posed a very serious threat to people helping Jews, and in the Eastern Borderlands – additionally collaborators and confidants of Ukrainian, Belarusian or Lithuanian origin.[8][12] Barbara Engelking emphasizes that due to the relatively weak saturation of rural areas with German police and gendarmerie units, a large part of the cases of exposing Poles hiding Jews had to be the result of reports submitted by their Polish neighbours. Dariusz Libionka reached similar conclusions.[2] However, the actual scale of denunciation has still not been thoroughly investigated.[2][13]

There were also cases when the captured Jews – under the influence of torture or false promises to save their lives – gave out aiding Poles to the German authorities. Jewish people were also among the informants of German police.[12]

Number of Poles murdered

The number of Poles murdered by the Germans for helping Jews has not yet been precisely determined. One of the reasons may be that people helping Jewish refugees were often murdered with whole families and hidden Jews.[25][26] Moreover, in the times of the People's Republic of Poland, no in-depth research was conducted into the problem of Polish aid to Jews. The first major publications on this subject appeared only in the 1960s. According to Grzegorz Berendt, the communist authorities did not, for various reasons, care about comprehensive examination of the phenomenon of aid or, more broadly, about Polish-Jewish relations during the Second World War. The official historiography focused rather on the search for positive behavioural examples, which could then be used for propaganda on internal and international level.[8][11]

Szymon Datner, the director of the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw, made the first to attempt to compile a list of Poles murdered for helping Jews.[27] In 1968 he published a brochure "Forest of the Righteous. A charter from the history of rescuing Jews in occupied Poland", in which he presented 105 documented cases of crimes committed by Germans against Poles who saved Jews. Datner established that 343 Poles were murdered because of the help given to Jews, and in 242 cases the victim's name was established. Among the identified victims were 64 women and 42 children.[28][16] Datner's estimates also showed that as much as 80% of executions took place in rural areas. About 65% of the victims were executed and another 5% were murdered by burning alive. The largest number of documented crimes took place respectively in Kraków Voivodeship, Rzeszów Voivodship, Warsaw Voivodeship, Warsaw, and Lublin Voivodeship. In addition, the largest number of victims died in the following voivodships: Kraków, Rzeszów, Lublin, Kielce and Warsaw. Datner also stated that these estimates were preliminary and incomplete, covering only cases examined up to April 1968.[16]

On behalf of the Main Commission for the Investigation of Nazi Crimes, Wacław Bielawski[27] was investigating cases of crimes committed by Germans due to aiding Jews. The archive of the Institute of National Remembrance in Warsaw contains a separate set of over 2,000 folders containing his materials. Based on the findings of the investigation, Bielawski developed a brochure entitled "The crimes committed on Poles by the Nazis for their help to Jews", which in the second edition of 1987 contained the names of 872 murdered people and information about nearly 1400 anonymous victims. In subsequent years this list was verified by the employees of the , which resulted in its partial reduction.[23][27] The third edition of the publication entitled “Those Who Helped: Polish Rescuers of Jews During the Holocaust” (Warsaw, 1997) included the names of 704 Poles murdered for helping Jews.[29][30] The findings of the Commission's employees showed that 242 inhabitants of the Kraków District, 175 inhabitants of the Radom District, 141 inhabitants of the Warsaw District and 66 inhabitants of the Lublin District were among the victims. The number of 704 murdered did not include Poles murdered in villages, which were to be destroyed by the Germans due to support for Jews. In 2014, INR historians estimated that Bielawski's brochure and the preparation of Those Who Helped.... are "archaic", but they remain "still representative of the topic discussed".[23]

On the basis of data collected until 2000, the Yad Vashem Institute identified over 100 Poles murdered due to the fact that they helped Jews. However, Israel Gutman estimated that the actual number of victims was "certainly expressed in hundreds".[25]

In 2005, the community gathered around the foundation Institute for Strategic Studies initiated a research project entitled "Index of Poles murdered and repressed for helping Jews during World War II". The Institute of National Remembrance, as well as the , the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, the Yad Vashem Institute, the German Historical Institute in Warsaw and the Jewish Historical Institute were invited to cooperate in the project. Researchers involved in the project conducted research in Polish and foreign archives (including church archives), as well as in museums, research institutions, press and Polish and foreign-language literature. As a result of these works, the Institute of National Remembrance and ISS Foundation published the "Facts of repression against Polish citizens for their help during World War II" (Warsaw 2014). It lists the names of 508 Polish citizens (both ethnic Poles and representatives of national minorities) who were repressed for helping Jews. According to the findings of the Registry it is clear that 221 of the 508 victims were executed or died in prisons and concentration camps.[23] A further thirteen have been sentenced to death, but there is no information on the execution of the sentence. Moreover, it was not possible to establish the fate of several dozen people who were sent to concentration camps or imprisoned in detention centers and prisons.

The Register is open and the information contained therein will be verified and supplemented. Furthermore, the first edition of it describes mainly those cases of retribution, the circumstances of which were usually not described in more detail before. For this reason, the list of 508 repressed people does not include the victims of some known crimes committed against Poles who helped Jews (including the Ulma family from Markowa, the families of Kowalski, Kosiors, Obuchiewiczs and Skoczylas from Stary Ciepiełów and Rekówka, the guardians of in Warsaw, Henryk Sławik).[23]

Other attempts were also made to establish the number of Poles murdered by the Germans for helping Jews. The Polish Association of Former Political Prisoners estimated the number of victims at ca. 2500. Wacław Zajączkowski in his work entitled "Martyrs of Charity" (edited by the Maximilian Kolbe Foundation, Washington 1988) mentioned the names of 2300 Poles who were to be executed for helping Jews.[31] Anna Poray-Wybranowska in her work entitled "Those Who Risked Their Lives" (Chicago, April 2008) included surnames of over 5 thousand victims.[32] Anna Zechenter writes that Anna Poray-Wybranowska in her work entitled "Those Who Risked Their Lives" (Chicago, April 2008) included surnames of over 5 thousand victims.[33]

Examples of retribution

The fate of the Ulma family from Markowa near Łańcut became the symbol of martyrdom of Poles murdered for helping Jews. In the second half of 1942 Józef Ulma received eight Jews from the Goldmans/Szall, Grünfeld and Didner families. A year and a half later, the Ulmas were denounced by Włodzimierz Leś, a "blue policeman" who took possession of the Szall family's property and intended to get rid of its rightful owners. On March 24, 1944, German gendarmes from Łańcut came to Markowa. They shot Józef Ulma, his wife Wiktoria (which was in an advanced pregnancy) and six children, the oldest of whom was eight years old and the youngest one and a half years old. Together with the Ulmas, all the Jews in hiding, including two women and a child, died.

In the winter of 1942 and 1943, the German Gendarmerie carried out a large-scale repressive action in the region of Ciepiełów, aimed at intimidating the Polish population and discouraging it from helping Jews. On December 6, 1942, 31 Poles were shot or burnt alive in the villages of Stary Ciepielów and Rekówka, mostly from the families of Kowalski, Kosior, Obuchiewicz and Skoczylas. There were also two Jewish escapees killed. Twenty children under the age of 18 were murdered. The youngest victim of the massacre was 7 months old, the oldest one was about 70 years old. Two days later, gendarmes murdered Marianna Skwira, who was involved with her husband in the campaign to help Jewish refugees. A distinctive culmination of the action was the murder carried out around January 11, 1943 in the village of Zajączków. The widow Stanisława Wołowiec, her four daughters aged from 6 months to 12 years, her brother-in-law Józef Jelonek and the farmstead Franciszek Zaborski were murdered there. The crimes were committed in retaliation for helping the Jewish refugees by the Wołowiec family. A series of executions against residents of the village near Ciepielów was one of the greatest crimes committed by Germans on Poles who helped Jews.

At least six repressive actions targeted at Poles helping Jews were carried out by gendarmes from neighbouring Lipsko during the same period. On December 14, 1942, Franciszek Osojca, his wife Aniela and their two-year-old son Zdzisław, were murdered in the village Okół. In December 1942 and January 1943, the Lipsko Gendarmerie carried out three repressive actions in the colony of Boiska near Solec nad Wisłą, during which they murdered 10 people from the families of Kryczek, Krawczyk and Boryczyk and two Jews hidden in the grove of Franciszek Parol (wife of the latter was imprisoned in Radom).

The large-scale repressive action against Poles supporting Jews was also carried out in the vicinity of the Paulinów village in the Sokolowski County. The immediate cause of the repressive action was the activity of a provocateur's agent, who pretending to escape from the transport to Treblinka camp, gained information about the inhabitants of the village who helped Jews. On February 24, 1943, the Paulinów village was surrounded by a strong penal expedition from Ostrów Mazowiecka. As a result of the pacification 11 local Poles were murdered. Three of the refugees who benefited from their assistance were also killed.

The repressive action against Poles supporting Jews was also carried out in Pantalowice in Przeworsk County. On December 4, 1942, a group of gendarmes and Gestapo members from Łańcut came to the village with a young Jewish girl, who was promised to save her life in exchange for naming Poles helping Jewish refugees. Six people identified by the girl were shot in the courtyard of one of the farms. In the house of Władysław Dec, who was murdered, the gendarmes found a picture of his three brothers, who were also identified by the Jewish woman as being food-suppliers. As a result, that same night the Germans went to the nearby village of Hadle Szklarskie, where they arrested and shot Stanisław, Tadeusz and Bronisław Dec.

In retaliation for supporting the Jewish escapees, the village of Przewrotne was pacified, or rather its neighborhood of Studzieniec. On December 1, 1942, a unit of the German gendarmerie arrived there, which surrounded the buildings and nearby forest. The Zeller family, hiding in Studziec, fell into the German hands. Four of its members were killed on the spot, and the temporarily spared Metla Zeller was tortured to give up her help. Despite the torture, the woman did not point anyone out. Therefore, she and six Polish men from the families of Dziubek, Drąg, Pomykała and Żak were shot.

Moreover, the following people died for helping Jews:[23]

- The Baranek family – on March 15, 1943 in Wincenty Baranek's farmhouse in the village of Siedliska near Miechów German policemen showed up, who found four Jewish men in a hiding-place between the house and the farm buildings. The escapees were shot on the spot, and soon afterwards Wincenty Baranek, his wife Łucja and their two underage sons (9-year-old Tadeusz and 13-year-old Henryk) were murdered. The execution was avoided by the stepmother of Wincenty Baranek, Katarzyna Baranek née Kopacz, who on the next day, however, was handed over to the Germans and shot in Miechów.

- Anna and Wincenty Buzowicz – the Buzowicz couple helped the Jews Sala Rubinowicz and Else Szwarcman in their escape from the ghetto in Kozienice, and then gave them shelter. Their cousin or friend Maria Różańska was supposed to give an identity card to a Jewish fugitive. All three of them were arrested and sentenced to death by a sentence of the Special Court in Radom on 3 April 1943. The Buzowicz family were executed, there was lack of information about the fate of Różańska.

- Karol and Tekla Chowaniakowie, Piotr and Regina Wiecheć, Karolina Marek – the families hid the Jewish couple in their farms in Zawoja for many months. The information on this matter reached the Germans after the refugees had moved to another place. In May 1943, the Gestapo arrested Karol Chowaniak, his son Stanisław, and Karolina Marek, who worked in their house. A month later, Tekla Chowaniak was arrested and in October 1943 Piotr and Regina Wiecheć were arrested. The Wiecheć couple were murdered at the Gestapo headquarters in Maków Podhalański, while the Chowaniak couple and Karolina Marek were murdered in the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. The son of the Chowaniak family was deported to forced labour in the Reich.

- Apolonia and Stanisław Gacoń – a couple from Januszkowice, hid a ten-year-old Jewish girl in their house in the Jasielsk County, they did not turn her down even though they were warned that this fact had become known to the Germans. On May 28, 1943, a group of Gestapo members from Jasło came to the house of the Gacoń, and shot the two spouses and the Jewish girl.

- Katarzyna and Michał Gerula, Roman Segielin – the Gerula family from Łodzinka Górna had been hiding seven Jews on their farm for several months, who were brought by Roman Segielin, their acquaintance. On 1 January 1944, officers of the Ukrainian Auxiliary Police arrested Michał Gerula and Roman Segielin, and two days later also Katarzyna Gerula. Three Poles were soon executed. Three Jews found in the Gerula farm were shot on the spot by Ukrainian police officers.

- Marianna and Mieczysław Holtzer – owners of the land property of the Celestynów in the Tomaszów Lubelski County. On October 2, 1942, they were shot dead by German gendarmes, as they defended the Jews who worked in their property.

- Helena, Krzysztof and Genowefa Janus, Zofia and Mieczysław Madej – about 6 or 7 Jews were hiding in the Dzwonowice lodge belonging to the Janus family near Biskupice near Pilica. Notified by a denunciation, the Germans appeared there on January 12, 1943. 3 members of the Janus family (woman and two children) were killed, Mieczysław Madej and his wife Zofia née Janus, as well as several hidden Jews. Among the caregivers, only Stanisław Janus and his son Bronisław, who lived outside the house at that time, survived.

- Katarzyna and Sebastian Kazak – the Kazak family from Brzóza Królewska, have repeatedly granted temporary shelter to Jewish refugees. On March 23, 1943, German gendarmes appeared on the Kazak farm with the assistance of "blue policemen". They found three Jews who were shot on the spot. The spouses Sebastian and Katarzyna Kazak were also murdered. Only two daughters of Kazaks avoided the deaths.

- Maria and Zygmunt Kmiecicik, Adam Czajka – in the summer of 1942 the Czajka family from Libusza accepted a Jewish man under their roof for some time. Less than one and a half years later, he fell into the hands of the Germans and revealed the identity of his guardians during the interrogation. In March 1944, the German police arrested Stanisław and Adam Czajka, as well as Zygmunt Kmiecik and his wife Maria née Czajka. Stanisław was released after some time, but his brother and sister were murdered in Montelupi prison in Kraków. Zygmunt Kmiecik was sent to a concentration camp where he probably died.

- Franciszka and Stanisław Kurpiel – the Kurpiel family lived in Leoncina, near Krasiczyn, where Stanisław was a warden. At the turn of 1942/43, the Kurpiel family hid 24 escapees from the Przemyśl ghetto in the farm buildings. As a result of the denunciation on May 21, 1944, officers of the Ukrainian Auxiiary Police arrived in Leoncin, arrested the Kurpiel family, their three daughters and four members of the Kochanowicz family, who also lived in the farm. 24 Jews captured were shot on the spot. Kochanowicz and Kurpiel's daughters were released after some time, but Stanisław and Franciszek were shot after a hard investigation.

- Władysław Łodej and his family – the Łodej family lived in the village of Lubienia, near Iłża. Władysław helped nearly 40 Jews to escape from the Iłża ghetto and then supplied them with food and supported them in other ways. In mid-December 1942, the Germans arrived in Lubenia for his arrest. They did not find him in his home, but murdered his parents Wojciech and Marianna Łodej. They also detained Wiktoria, the wife of the one wanted, and their four children, the oldest of whom were fourteen years old and the youngest six. All five were executed on 21 December in the forest inspectorate of Marcule. Władysław Łodej survived his loved ones for ten days. On December 31, 1942, he was arrested and murdered by a "blue policeman".

- Ludomir Marczak and Jadwiga Sałek-Deneko – Marczak, composer and socialist activist, was involved in underground activities during the occupation. Together with his wife Marianna Bartułd, was hiding escapees from the Warsaw ghetto in an apartment on Pańska Street and in the shelter on Świętojarska Street. On November 25, 1943, notified Germans sized the second hiding place mentioned above, where they arrested Marczak, his co-worker Jadwiga Sałek-Deneko ps. "Kasia" and thirteen Jews. After a heavy investigation, Marczak was executed, "Kasia" and captured escapees were also executed.

- The Olszewski family – in the autumn of 1942, the Olszewski family from Skórnice near Końskie received ten Jews from the Wajntraub family under their roof. On 16 April 1943, probably due to denunciation, Germans arrived on the farm. Eight Jews hiding in the dugout were slaughtered with grenades. Janina Olszewska, her four children aged between one and eight years (Krystina, Jan, Bogdan, Zofia), as well as Maria Olszewska and her eleven-year-old son Marian, were shot. Henryk Olszewski (husband of Janina) and Leon Olszewski were deported to concentration camps, where they died. Only those who survived from the Olszewski family were Władysław and Wojciech Olszewski (stepson and son of Maria) as they were not in the house.

- Helena and Jan Prześlak – teachers and social activists from Jaworzno, who in July 1942 helped a dozen or so escapees from the local ghetto to hide in the school in the Jaworzno's district of Stara Huta. On the night of 12/13 July 1942, most likely due to denunciation, the couple were arrested by the Gestapo. After a short stay in the prison in Mysłowice, they were sent to the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp, where they died in September 1942.

- Zofia and Wojciech Puła from Małec helped the Jewish refugees. On November 8, 1942, together with their son Władysław and daughters Janina and Izabela, they were arrested by the Germans. All five were imprisoned in the prison in Brzesko, and then transferred to the Montelupi prison in Kraków, after which they were deported to the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp. Only Władysłąw Puła survived.

- Franciszek Paweł Raszeja – orthopaedic doctor, professor of medical sciences, head of the surgical department of Warsaw's Polish Red Cross Hospital. He went to the Warsaw Ghetto many times for consultations. On July 21, 1942, he was murdered by the Germans in his apartment at Chłodna Street, where he helped a Jewish patient[186]. Kazimierz Pollak and Jews who were in the apartment were probably killed with him.

- The family of Rębiś, Feliks Gawryś and Zofia Miela – the family of Rębiś from the village of Połomia in the Dębica County took at least ten Jews under their roof in 1942. Moreover, the Rębiś family helped to prepare a hiding place for the Jewish Buchner family in the neighbouring farm belonging to Zofia Miela. On September 9, 1943, Germans appeared in the village with the assistance of "blue policemen". They murdered Anna and Józef Rębiś, their daughters Zofia and Victoria, son Karol, as well as Feliks Gawryś (a fiancée of Victoria), who lived in their house. Hidden Jews were also murdered (only one survived). Five days later the Germans returned to Połomia and murdered Zofia Miela.

- Maria Rogozińska and her three-year-old son Piotr – in the Rogoziński farmstead in Wierbka village in Olkusz County (present Zawiercie County) Jews and members of the underground were hidden. Around January 11, 1943, German gendarmes appeared there, and shot two hiding Jews on the spot, as well as two Polish men.[34] On the same day Marianna Rogozińska and her three-year-old son Peter fell into the hands of the Germans. Both of them were taken to the German Gendarmerie headquarters in Pilica Castle, where they were murdered after a brutal interrogation.

- Adam Sztark – a Jesuit priest serving in Słonim. During the occupation, he called to help the Jews from the pulpit, collected money and valuables for them, organized "Aryan" documents, and helped hide and save an orphaned Jewish child. He was executed by the Germans in December 1942.

- Mieczysław Wolski and Janusz Wysocki – caretakers of the so-called "Krysia" bunker in Warsaw's Ochota district, where in 1942–1944 about 40 Jews were hiding, including the historian Emanuel Ringelblum with his wife and son. On March 7, 1944 the hiding place was discovered by the Gestapo, and Mieczysław and Janusz together with those under their care were arrested. A few days later, all of them were shot in the ruins of the Warsaw Ghetto.

Some authors consider helping Jews as the reason of pacification of such villages[35] as: Bór Kunowski (3/4 July 1943, 43 victims), Cisie (28 June 1943, 25 victims), Krobonosz (26 May 1942, 15 victims), Liszno (18 May 1942, 60 victims, Obórki (November 1942, at least several dozen victims), Parypse (22 May 1942, 8 victims), Przewrotne (14 March 1943, 36 victims), Staw (26 May 1942, 8 victims), Tarnów (May 1942, 40 victims), Widły (26 May 1942, several dozen victims), Wola Przybysławska[36] (10 December 1942, 19 victims).[12][37]

Repercussions

Analysing the impact of the German acts of retribution on the attitude of Poles towards Jewish refugees, one should take into account the fact that decisions on the possible granting of aid were taken in a situation where significant parts of the Polish nation were exterminated, and the entire ethnic Polish population remained under threat of Nazi terror.[11][12][16] The first months of the German governments have already made Polish society aware that even minor violations of the occupation order will be punished with absolute and cruel punishment. In addition, the Germans deliberately tried to publicise the retribution meted on people supporting Jews, thus intimidating Polish society and discouraging them from taking any support measures.[38][8] Many historians believe that the fear of German retribution was one of the most important factors discouraging Poles from helping Jewish refugees[26][14] (other important factors are: significant number of Jewish minority and its low assimilation rate, anti-Semitism, war poverty and demoralisation).[11][6]

Some historians have come to the conclusion that the main motivation of those helping Jews was the desire for profit,[22] Jan Tomasz Gross came to the conclusion that hiding the fugitives could not be a particularly risky occupation, because in his opinion few people would endanger their own lives and those of their loved ones only for the sake of income. Gunnar S. Paulsson compared the minimum number of Poles involved in rescuing Jews (160,000) with the number of about 700 people reported killed by GKBZpNP-IPN, and concluded that the probability of death for this reason was between 1 and 230. Taking into account the remaining threats to which Poles under German occupation were exposed, he decided that helping Jews in practice was only to some extent more risky than other offences against the occupation order. In his assessment:[15]

The draconian rules applied on a massive scale, instead of trivialising the population, led it to bereavement and created a climate of lawlessness in which[...] hiding Jews simply became one of the many illegal activities in which people routinely risked their lives. The principle of collective responsibility also had the opposite effect, because denunciation of the Jew brought danger to his Polish guardians, which meant a violation of the occupational order for solidarity.

Other historians have estimated however that the percentage of Poles acting solely on financial grounds was only from several to twenty[11] percent. Marcin Urynowicz points out that German terror was very effectively intimidating wide circles of Polish society, hence the real threats faced by the person to whom assistance was requested did not have a direct connection with the level of fear she felt. In conclusion, he states:[14]

Thanks to the understanding of this phenomenon we can learn much better of the situation of a Pole who faced a dilemma: to help a person in danger or not. It was no longer more important whether the person who was asked to help was actually risking something at a given time and place. What matters was whether this person, subjected to long-term stress and anxiety, was able to overcome her own weaknesses, overcome something much deeper than the feeling of fear, or whether she was able to experience the terror of the invader targeted directly at her and her loved ones.

Barbara Engelking points out that the fear of German repression grew, especially when there were cases of executions of Poles suspected of supporting Jewish refugees in a certain area. Such events often had a major impact on the situation of Jews in hiding.[13] There are known cases where the demonstrative repressive actions carried out by the Germans, and even the threat of severe punishments themselves, have reached the goal of intimidating the local population and significantly reducing aid to Jews.[39] In some cases, the fear of denunciation and severe penalties resulted in the expulsion of fugitives into the hands of Germans. It also happened that Poles who, for various reasons, could not or did not want to hide Jewish fugitives, preferred to murder them instead of allowing them to seek refuge elsewhere.[13] According to one of the Jewish survivors the story of the massacre of the Ulma family made such a shocking impression on the local population that the bodies of 24 Jews were later found in the Markowa area, where Polish caregivers murdered them because of fear of denunciation.[40] However, according to the historian , this crime took place in the neighbouring Sietsza village – in addition, most probably two years before the Ulmas' death.[41]

Numbers of those who helped and survivors

believed that "in the conditions of the Nazi occupation terror, unprecedented elsewhere, saving Jews in Poland grew to an act of special sacrifice and heroism".[42] However, in Polish society there were people willing to take such a risk. Gunnar S. Paulsson estimated that there were 280,000 to 360,000 Poles involved in various forms of aid to Jews,[15] of which about 70–90,000 in Warsaw alone. Teresa Prekerowa estimated the number of helpers at 160–360 thousand,[6] Marcin Urynowicz at 300 thousand,[11] and Władysław Bartoszewski at "at least several hundred thousand".[12] According to Jan Żaryn, the number of Poles participating directly or indirectly in the rescue of Jews could reach even one million, and according to Richard Lukas – at least from 800,000 to 1.2 million.[43]

It is difficult to determine the number of Jews who survived the German occupation, hiding among Poles. Shmuel Krakowski claimed that not more than 20 thousand people survived on the Aryan side. Israel Gutman estimated that about 50 thousand Jews survived in the occupied territory of Poland, of which between 30 thousand and 35 thousand survived thanks to the help of Poles. According to estimates by Teresa Prekerowa, between 30 thousand and 60 thousand Jews survived by hiding among the Polish population ("with or without their help").[44] Grzegorz Berendt estimated that in occupied Poland about 50 thousand Jews "on the Aryan side" survived. Gunnar S. Paulsson, on the other hand, estimated that about 100 thousand Jews were hiding in occupied Poland, of which nearly 46 thousand managed to survive the war. According to him, 28 thousand Jews were hiding in Warsaw alone, of which nearly 11.5 thousand were saved.

Comparison with the situation in other occupied countries in Europe

Marek Arczyński pointed out that "in no occupied country did the Nazis use such far-reaching repressive and cruel terror for the help of the Jewish population as in Poland".[42] Other historians also formulated similar opinions. Contrary to the widespread stereotype, Poland was not, however, the only occupied country in Europe, where any aid to Jews was threatened by the death penalty. The principle of collective responsibility for helping Jews in hiding was introduced by the Germans in the occupied territories of the USSR and in the occupied Balkan states, i. e. in countries where under the pretext of fighting against partisans they abandoned the observance of the rules of humanitarian law.

On the other hand, much less risk was associated with helping Jews in the occupied countries of Western Europe or in states allied with the Third Reich.[14] The granting of aid to Jews was usually punished there by confiscation of property, imprisonment or deportation to a concentration camp. For example, two Dutchmen were arrested for helping Anna Frank's family, none of whom were executed.[45] Stefan Korboński claimed that in Belgium, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, there was not a single case of death sentence imposed on a person helping Jewish fellow citizens. Only in Denmark there was an incident when a man was shot dead when he was helping Jews to get on a ferry to neutral Sweden. However, the Yad Vashem Institute points out that there are known cases of deaths of Western European citizens in concentration camps, to which they were deported due to aiding Jews. Nevertheless, the difference between the reality of occupied Poland and the situation in Western European countries may be measured by the fact that in Holland it was possible to organise public protests against deportations of the Jewish population.[12]

Calculations by Teresa Prekerowa show that only 1% to 2.5% of the adult Polish population was involved in helping Jews.[46] In Western Europe the number of helpers was similarly small, though the risk associated with these activities was incomparably lower.[14]

Assuming the percentage of the population of European countries, which in 1945 was made up of Jews who survived the Holocaust, Poland did not differ from the average in other occupied states. On the other hand, in the Netherlands, where few Jews lived and anti-Semitic sentiments were much weaker than in Poland, the losses of the Jewish population were, in percentage terms, comparable with the losses of Polish Jews. Gunnar S. Paulsson estimated that among the Jews that attempted to hide on the Aryan side in Warsaw and Holland, the percentage of survivors was almost identical. Moreover, his calculations show that the "loss ratio" of Warsaw Jews and Danish Jews was almost identical. Paulsson stated, however, that for various reasons Jews who attempted to hide in the rural areas of occupied Poland had much less chance of survival.[15]

Commemoration

By 1 January 2016, the number of Poles honored with the medal "Righteous Among the Nations" was 6620. The Honoured are, in most cases, people who are not connected with the broadly understood resistance movement and who provided help to Jews on their own account. Among the honored were a number of Poles who died as a result of helping Jews, including five members of the Baranek family, Michał and Katarzyna Gerula, Sebastian and Katarzyna Kazak, Henryk, Janina, Maria and Leon Olszewski, prof. Franciszek Paweł Raszeja, Maria Rogozińska, Jadwiga Sałek-Deneko, Fr Adam Sztark, Józef and Wiktoria Ulma, Mieczysław Wolski and Janusz Wysocki.[23]

Monuments commemorating Poles who saved Jews during World War II were erected in Kielce (1996) and Łódź (2009). On March 24, 2004 in Markowa, a monument commemorating the Ulma family was unveiled. In addition, on March 17, 2016, the Museum of Poles Saving Jews during the Second World War named after Ulma family in Markowa was opened.

In 2008, the Institute of National Remembrance and the National Cultural Centre initiated an educational campaign "Life for life" aimed at showing the attitudes of Poles who risked their lives to save Jews during the Second World War.

In March 2012, the National Bank of Poland introduced coins commemorating three Polish families murdered for helping Jews – the Kowalski family from Stary Ciepiełów, the Ulma family from Markowa and the Baranek family from Siedliska.

The stories of Poles murdered by the Germans for providing help to Jews were presented in documentaries entitled "Price of Life" from 2004 (dir. Andrzej Baczyński), "Righteous Among the Nations" from 2004 (dir. Dariusz Walusiak), "Life for Life" in 2007 (dir. Arkadiusz Gołębiewski)[273], "Historia Kowalskich" 2009 (dir. Arkadiusz Gołębiewski, Maciej Pawlicki).

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r 1968–, Młynarczyk, Jacek Andrzej (2007). Cena poświęcenia : zbrodnie na Polakach za pomoc udzielaną Żydom w rejonie Ciepielowa. Piątkowski, Sebastian. Kraków: Instytut Studiów Stategicznych. ISBN 9788387832629. OCLC 313476409.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Akcja Reinhardt : zagłada Żydów w Generalnym Gubernatorstwie. Libionka, Dariusz., Instytut Pamięci Narodowej—Komisja Ścigania Zbrodni przeciwko Narodowi Polskiemu. Warszawa: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej. 2004. ISBN 8389078686. OCLC 58471005.CS1 maint: others (link)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af Eisenbach, Artur (1961). Hitlerowska polityka zagłady Żydów. Książka i Wiedza.

- ^ a b c )., Mallmann, Klaus-Michael (1948– ) (cop. 2009). Einsatzgruppen w Polsce. Matthäus, Jürgen (1959– )., Ziegler-Brodnicka, Ewa (1931– )., Böhler, Jochen (1969– ). Warszawa: Bellona. ISBN 9788311115880. OCLC 750967085. Check date values in:

|date=(help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ The anonymous author of this memorial assumed that for economic and logistic reasons it would be impossible to fully isolate Jews from the Polish element. For this reason, he recommended the occupation authorities to create mixed settlement districts (Polish-Jewish, Polish-Ukrainian, etc.) in order to fuel antagonisms on the grounds of nationality. See Eisenbach 1961?, pp. 171–172.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Teresa., Prekerowa (1982). Konspiracyjna Rada Pomocy Żydom w Warszawie 1942–1945 (Wyd. 1 ed.). Warszawa: Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy. ISBN 8306006224. OCLC 9254955.

- ^ Warszawa walczy 1939–1945 : leksykon. Komorowski, Krzysztof. Warszawa. 2014. ISBN 9788311134744. OCLC 915960200.CS1 maint: others (link)

- ^ a b c d e f g h Barbara Polak. Biedni Polacy patrzą i ratują. Z Grzegorzem Berendtem, Markiem Wierzbickim i Janem Żarynem rozmawia Barbara Polak. „Biuletyn IPN”. 3 (98), 2009–03.

- ^ a b c d e 1900–1944., Ringelblum, Emanuel (1988). Stosunki polsko-żydowskie w czasie drugiej wojny światowej : uwagi i spostrzeżenia. Eisenbach, Artur. (Wyd. 1 ed.). Warszawa: Czytelnik. ISBN 830701686X. OCLC 18481731.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- ^ a b Timothy., Snyder (2011). Skrwawione ziemie : Europa między Hitlerem a Stalinem. Warszawa: Świat Książki. ISBN 9788377994566. OCLC 748730441.

- ^ a b c d e f Polacy i Żydzi pod okupacją niemiecką 1939–1945 : studia i materiały. Żbikowski, Andrzej., Instytut Pamięci Narodowej—Komisja Ścigania Zbrodni przeciwko Narodowi Polskiemu. Warszawa: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej—Komisja Ścigania Zbrodni przeciwko Narodowi Polskiemu. 2006. ISBN 8360464014. OCLC 70618542.CS1 maint: others (link)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Władysław., Bartoszewski (2007). Ten jest z ojczyzny mojej : Polacy z pomocą Żydom, 1939–1945. Lewinówna, Zofia. (Wyd. 3, uzup ed.). Warszawa: Stowarzyszenie ŻIH/Świat Książki. ISBN 9788324707157. OCLC 163569372.

- ^ a b c d e 1962–, Engelking, Barbara (2011). Jest taki piękny słoneczny dzień-- : losy Żydów szukających ratunku na wsi polskiej 1942–1945 (Wyd. 1 ed.). Warszawa: Stowarzyszenie Centrum Badań nad Zagładą Żydów. ISBN 9788393220229. OCLC 715148392.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- ^ a b c d e f g Złote serca czy złote żniwa? : studia nad wojennymi losami Polaków i Żydów. Chodakiewicz, Marek Jan, 1962–, Muszyński, Wojciech Jerzy, 1972– (Wyd. 1 ed.). Warszawa: Wydawn. "The Facto". 2011. ISBN 9788361808053. OCLC 738435243.CS1 maint: others (link)

- ^ a b c d e f S., Paulsson, Gunnar (2009). Utajnione miasto : żydzi po aryjskiej stronie Warszawy (1940–1945). Olender-Dmowska, Elżbieta., Engelking, Barbara, 1962–, Leociak, Jacek. (Wyd. 2 ed.). Kraków: Wydawn. Znak. ISBN 9788324012527. OCLC 651998013.

- ^ a b c d e f Datner, Szymon (1968). Las sprawiedliwych. Karta z dziejów ratownictwa Żydów w okupowanej Polsce. Warszawa: Książka i Wiedza.

- ^ In most cases, the Third Order limiting residence in the General Government of 15 October 1941 was cited as the legal basis for these provisions; see Bartoszewski i Lewinówna 2007?, pp. 652–654.

- ^ A few days later, announcements with a similar content were published in all counties of the district. See: Młynarczyk and Piątkowski 2007?, p. 70.

- ^ Der Hilfsrat für Juden "Zegota" 1942–1945 : Auswahl von Dokumenten. Kunert, Andrzej Krzysztof,, Polska. Rada Ochrony Pamie̜ci Walk i Me̜czeństwa. Warschau: Rada Ochrony Pamie̜ci Walk i Me̜czeństwa. 2002. ISBN 8391666360. OCLC 76553302.CS1 maint: others (link)

- ^ On July 18, 1943, the head of the Chief Justice Department of the "Government" of the General Government, Kurt Wille, issued a circular addressed to the "District Justice Offices", in which he noted that in the event "when it is not possible to state, whether a Jew has left the district designated to him in an unauthorised manner, and it is merely stated that he has not been allowed to enter the district outside his housing district" there is no direct legal basis for punishing the person who gave shelter to such a Jew. However, he ordered that when dealing with cases of aid to Jews, one should also take into account in such cases "the basic idea contained in § 4b, point 1, sentence 2, of combating the political, criminal and health dangers emanating from Jews". In particular, he recommended that the death penalty be imposed on Poles assisting those Jews who did not comply with the order to settle in ghettos from the very beginning. See Datner 1968?, p. 18.

- ^ Stefan., Korboński (2011). Polacy, żydzi i holocaust. Waluga, Grażyna., Instytut Pamięci Narodowej—Komisja Ścigania Zbrodni przeciwko Narodowi Polskiemu. Warszawa: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej—Komisja Ścigania Zbrodni przeciwko Narodowi Polskiemu. ISBN 9788376292700. OCLC 747984730.

- ^ a b Tomasz., Gross, Jan (2011). Złote żniwa : rzecz o tym, co się działo na obrzeżach zagłady Żydów. Grudzińska-Gross, Irena. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Znak. ISBN 9788324015221. OCLC 719373395.

- ^ a b c d e f g Aleksandra Namysło, Grzegorz Berendt (red.): Rejestr faktów represji na obywatelach polskich za pomoc ludności żydowskiej w okresie II wojny światowej. Warszawa: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej i Instytut Studiów Strategicznych, 2014. ISBN 978-83-7629-669-2.

- ^ Sebastian Piątkowski. Za pomoc Żydom osadzeni w więzieniu radomskim. „Biuletyn IPN”. 3 (98), 2009–03.

- ^ a b Księga Sprawiedliwych wśród Narodów Świata : ratujący Żydów podczas Holocaustu : Polska. Krakowski, Shmuel., Gutman, Israel., Bender, Sara., Yad ṿa-shem, rashut ha-zikaron la-Shoʼah ṿela-gevurah. Kraków: Fundacja Instytut Studiów Strategicznych. 2009. ISBN 9788387832599. OCLC 443558424.CS1 maint: others (link)

- ^ a b 1937-, Lukas, Richard C. (2012). Zapomniany Holocaust : Polacy pod okupacją niemiecką 1939–1944. Stodulski, Sławomir., Davies, Norman, 1939– (Wyd. 2, popr., uzup. i rozsz ed.). Poznań: Dom Wydawniczy Rebis. ISBN 9788375108323. OCLC 822729828.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- ^ a b c Wacław Bielawski: Zbrodnie na Polakach dokonane przez hitlerowców za pomoc udzielaną Żydom. Warszawa: GKBZH-IPN, 1987.

- ^ Datner also established that 248 Jews and four Soviet escapees were murdered together with 343 Poles. See Datner 1968?, p. 115.

- ^ The list includes both Poles murdered by the Germans and a few cases in which people hiding Jews were murdered by Ukrainian nationalists or common bandits. See Walczak et al. 1997 ↓, s. 52,61,96.

- ^ Those who helped : Polish rescuers of Jews during the Holocaust. Juskiewicz, Ryszard., Śliwczyński, Jerzy Piotr., Zakrzewski, Andrzej., Główna Komisja Badania Zbrodni przeciwko Narodowi Polskiemu—Instytut Pamięci Narodowej., Polskie Towarzystwo Sprawiedliwych Wśród Narodów Świata. Warszawa: Main Commission for the Investigation of Crimes against the Polish Nation—The Institute of National Memory. 1993–<1997>. ISBN 839088190X. OCLC 38854070. Check date values in:

|date=(help)CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ In 2011, the Institute of National Remembrance indicated that Wacław Zajączkowski's book "has no scientific character and contains numerous errors". However, the Institute said that "the number of Poles being persecuted for helping Jews may turn out to be a short way from the truth". See Korboński 2011?, p. 69.

- ^ Anna Zechenter. Jedenaste: przyjmij bliźniego pod swój dach. „Biuletyn IPN”. 3 (98), 2009–03.

- ^ Anna Zechenter. Jedenaste: przyjmij bliźniego pod swój dach. „Biuletyn IPN”. 3 (98), 2009-03.

- ^ One of the murdered Poles was Piotr Podgórski. He was to be shot dead because he did not inform the German authorities about the hiding of Jews in Wierbce, although as a village guard he was obliged to do so. See Namysło 2009?, pp. 126 and 128.

- ^ In a few cases, in addition to the aid given to Jews, assistance provided to the Soviet escapees and partisans was considered to be a cause of pacification. See Fajkowski and Religa 1981?, pp. 57–60, 322.

- ^ Dariusz Libionka pointed out that the investigation into the pacification of Wola Przybyrosławska by the District Commission for the Investigation of Nazi Crimes in Lublin did not confirm the thesis that the cause of the crime was aid provided by the villagers to Jews. Of the thirteen witnesses questioned, only two connected the death of three of the nineteen victims with the aid given to Jews. See Libionka 2004?, pp. 323–324.

- ^ Józef Fajkowski, Jan Religa: Zbrodnie hitlerowskie na wsi polskiej 1939–1945. Warszawa: Książka i Wiedza, 1981.

- ^ In the Nazi reality, information about the crimes perpetrated by the Germans on people helping Jews was often exaggerated, which had an even greater impact on social sentiments. For example, rumours were circulating in Warsaw about the alleged burning of whole tenement houses, where Jewish escapees were found. See Ringelblum 1988?, p. 116.

- ^ Przemysław Kucharczak. Życie za Żyda. „Gość Niedzielny”. 49 (2007), 2007-12-09.

- ^ "Jozef & Wiktoria Ulma". Yad Vashem. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- ^ Mateusz Szpytma. Sprawiedliwi i inni. „Więź”. 10 (2011), 2011–10.

- ^ a b Marek., Arczyński (1983). Kryptonim "Żegota". Balcerak, Wiesław. (Wyd. 2 ed.). Warszawa: Czytelnik. ISBN 8307008328. OCLC 12163510.

- ^ 1937-, Lukas, Richard C. (2012). Zapomniany Holocaust : Polacy pod okupacją niemiecką 1939–1944. Stodulski, Sławomir., Davies, Norman, 1939– (Wyd. 2, popr., uzup. i rozsz ed.). Poznań: Dom Wydawniczy Rebis. p. 403. ISBN 9788375108323. OCLC 822729828.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- ^ Prekerowa estimated that 380 thousand to 500 thousand Polish Jews survived the war. In addition to those who survived while hiding among Poles, she included the number of Jews who found themselves in the unoccupied territory of the USSR (over 200 thousand), they survived the war, protecting themselves in forest "survival camps" or in the ranks of partisans (from 10 thousand). They managed to survive in German concentration camps (from 20,000 to 40,000) and they also served in the ranks of the Polish Armed Forces in the West and fled to other countries. See Prekerowa 1993?, p. 384.

- ^ These were Viktor Kugler and Johannes Kleiman. Both of them were arrested on August 4, 1944 and after a few weeks stay in Amsterdam prisons, they were transported to the labour camp in Amersfoort (September 11). Kleiman has been released on 18 September due to ill health. Kugler, on the other hand, was imprisoned until 1945, when he fled from the camp, thus avoiding deportation to Germany for forced labour. See Frank 2015?, p. 313.

- ^ Polonsky, Antony (1990). My brother's keeper? Recent Polish debates on the Holocaust. Oxford: Routledge. ISBN 9780415755399. OCLC 927100967.

- Rescue of Jews by Poles in occupied Poland in 1939-1945

- Nazi war crimes