Łódź

Łódź

Lodz (English) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Motto(s): Ex navicula navis ("From a boat a ship") | |

Łódź Location of Łódź in Łódź Voivodeship  Łódź Łódź (Poland) | |

| Coordinates: 51°46′37″N 19°27′17″E / 51.77694°N 19.45472°ECoordinates: 51°46′37″N 19°27′17″E / 51.77694°N 19.45472°E | |

| Country | |

| Voivodeship | |

| County | city county |

| City Rights | 1423 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Hanna Zdanowska (PO) |

| Area | |

| • City | 293.25 km2 (113.22 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 278 m (912 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 162 m (531 ft) |

| Population (31 December 2019) | |

| • City | 679,941 |

| • Density | 2,320/km2 (6,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 1,100,000 |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 90-001 to 94–413 |

| Area code(s) | +48 42 |

| Car plates | EL |

| Website | www |

Łódź (Polish: [wutɕ] (![]() listen)), written in English as Lodz,[a] is the third-largest city in Poland and a former industrial centre. Located in the central part of the country, it has a population of 679,941 (2019).[1] It is the capital of Łódź Voivodeship, and is located approximately 120 kilometres (75 mi) south-west of Warsaw.[6] The city's coat of arms is an example of canting, as it depicts a boat (łódź in Polish), which alludes to the city's name.

listen)), written in English as Lodz,[a] is the third-largest city in Poland and a former industrial centre. Located in the central part of the country, it has a population of 679,941 (2019).[1] It is the capital of Łódź Voivodeship, and is located approximately 120 kilometres (75 mi) south-west of Warsaw.[6] The city's coat of arms is an example of canting, as it depicts a boat (łódź in Polish), which alludes to the city's name.

Łódź was once a small settlement that first appeared in 14th-century records. It was granted town rights in 1423 by Polish King Władysław II Jagiełło, and it remained a private town of the Kuyavian bishops and clergy until the late 18th century. The Second Industrial Revolution brought rapid growth in textile manufacturing and in population due to the inflow of migrants, notably Germans and Jews. Ever since the industrialization of the area, the city has struggled with multinationalism and social inequalities, which were documented in the novel The Promised Land by Nobel Prize-winning author Władysław Reymont. The contrasts greatly reflected on the architecture of the city, where luxurious mansions coexisted with redbrick factories and dilapidated tenement houses.[7]

The industrial development and demographic surge made Łódź one of the largest cities in Poland. Under the German occupation during World War II, Łódź was briefly renamed to Litzmannstadt in honour of Karl Litzmann. The city's large Jewish population was forced into a walled zone known as the Łódź Ghetto, from which they were sent to German concentration and extermination camps. The city became Poland's temporary seat of power in 1945.

Łódź experienced a sharp demographic and economic decline after 1989. It was only in the 2010s that the city began to experience revitalization of its neglected downtown area.[8][9] Łódź is ranked by the Globalization and World Cities Research Network on the “Sufficiency” level of global influence[10] and is internationally known for its National Film School, a cradle for the most renowned Polish actors and directors, including Andrzej Wajda and Roman Polanski.[7] In 2017, the city was inducted into the UNESCO Creative Cities Network and named UNESCO City of Film.[11]

History[]

Łódź first appears in the written record in a 1332 document of Duke Władysław the Hunchback giving the village of Łodzia to the bishops of Włocławek. In 1423 King Władysław II Jagiełło officially granted city rights to the village of Łódź. From then until the 18th century the town remained a small settlement on a trade route between the provinces of Masovia and Silesia. In 1496, Polish King John I Albert confirmed the establishment of two annual fairs and a weekly market in Łódź. In the 16th century the town had fewer than 800 inhabitants, mostly working on the surrounding grain farms.

With the second partition of Poland in 1793, Łódź became part of the Kingdom of Prussia's province of South Prussia, and was known in German as Lodsch. In 1798 the Prussians nationalised the town, and it lost its status as a town of the bishops of Kuyavia. In 1806 Łódź joined the Napoleonic Duchy of Warsaw and in 1810 it had approximately 190 inhabitants. After the 1815 Congress of Vienna treaty it became part of the Congress Kingdom of Poland, a client state of the Russian Empire.

Century of partitions: 1815 Congress of Vienna[]

In the 1815 treaty, it was planned to renew the dilapidated town and with the 1816 decree by the Czar a number of German immigrants received territory deeds for them to clear the land and to build factories and housing. Their incentives for settlement included "exemption from tax obligations for a period of six years, free materials to build houses, perpetual lease of land for construction, exemption from military service or duty-free transport of the immigrants’ livestock."[12] In 1820 Stanisław Staszic aided in changing the small town into a modern industrial centre. The immigrants came to the Promised Land (Ziemia obiecana, the city's nickname) from all over Europe. Mostly they arrived from Saxony, Silesia and Bohemia, but also from countries as far away as Portugal, England, France and Ireland.[citation needed] The first cotton mill opened in 1825, and 14 years later the very first steam-powered factory in both Poland and the Russian Empire commenced operations. In 1839, over 78% of the population was German,[13] and German schools and churches were established.

A constant influx of workers, businessmen and craftsmen from all over Europe transformed Łódź into the main textile production centre of the mighty Russian Empire spanning from East-Central Europe all the way to Alaska. As long as the town was small, the majority of the town's population was German speaking.[14] Three groups then dominated the city's population and contributed the most to the city's development: Germans, Poles, and Jews, who started to arrive from 1848. Many of the Łódź craftspeople were weavers from Upper and Lower Silesia.

In 1850, Russia abolished the customs barrier between Congress Poland and Russia proper and therefore industry in Łódź could now develop freely with a huge Russian market not far away. Eventually the city became the second-largest city of Congress Poland. In 1865 the first railroad line opened (to Koluszki, branch line of the Warsaw–Vienna railway), and soon the city had rail links with Warsaw and Białystok.

One of the most important industrialists of Łódź was Karl Wilhelm Scheibler.[15] In 1852 he came to Łódź and with Julius Schwarz together started buying property and building several factories. Scheibler later bought out Schwarz's share and thus became sole owner of a large business. After he died in 1881 his widow and other members of the family decided to pay homage to his memory by erecting a chapel, intended as a mausoleum with family crypt, in the Lutheran part of the Łódź cemetery on ulica Ogrodowa (later known as The Old Cemetery).[16]

Between 1823 and 1873, the city's population doubled every ten years. The years 1870–1890 marked the period of most intense industrial development in the city's modern history. Many of the industrialists were of Jewish ethnicity. Łódź also soon became a major centre of the socialist movement. One of the first strikes broke out in the Scheibler's factory in 1872, followed by the so-called (pl) in 1892, that paralyzed most of the factories and manufacturing plants and was ended by a military intervention.[17] According to the Russian census of 1897, in which Łódź figured as the fifth-largest city of the Russian Empire,[18] out of the total population of 315,000, Jews constituted 99,000 (around 31%).[19] In 1899, brothers Władysław and Antoni Krzemiński from the Polish noble family of Krzemiński of Prus III coat of arms founded the first cinema in Poland (Gabinet Iluzji) at Piotrkowska Street.[20] During the 1905 Revolution, in what became known as the June Days or Łódź insurrection, Tsarist police killed hundreds of workers.[21] By 1913, the German population had fallen from 78% in 1839 [13] to 14.8%, the Poles constituted almost half of the population (49.7%), and the Jews made up 34%, out of some 506,000 inhabitants.[13]

Despite the air of impending crisis preceding World War I, the city grew constantly until 1914. By that year it had become one of the most densely populated as well as one of the most polluted industrial cities in the world—13,280 inhabitants per square kilometre (34,400/sq mi). A major battle was fought near the city in late 1914, and as a result the city came under German occupation after 6 December[22][23][24] but with Polish independence restored in November 1918 the local population liberated the city and disarmed the German troops. In the aftermath of World War I, Łódź lost approximately 40% of its inhabitants, mostly owing to draft, diseases, pollution and primarily because of the mass expulsion of the city's German population back to Germany.

Restored Poland after the First World War[]

In 1922, following the establishment of the Second Polish Republic, Łódź became the capital of the Łódź Voivodeship, but the period of rapid growth had ceased. The Great Depression of the 1930s and the Customs war with Germany closed western markets to Polish textiles while the Bolshevik Revolution (1917) and the Civil War in Russia (1918–1922) put an end to the most profitable trade with the East. The city became a scene of a series of huge workers' protests and riots in the interbellum.

On 13 September 1925 a new airport, Lublinek Airport, began operations on the outskirts of the city. In the interwar years Łódź continued to be a diverse and multicultural city, with the 1931 Polish census showing that the total population of roughly 604,000 included 375,000 (59%) Poles, 192,000 (32%) Jews and 54,000 (9%) Germans (determined from the main language used). By 1939, the Jewish minority had grown to well over 200,000.[25]

Occupation of Poland by Nazi Germany[]

During the invasion of Poland, the Polish forces of General Juliusz Rómmel's Łódź Army defended the city against initial German attacks.[26] The Wehrmacht nevertheless captured the city on 8 September.[26] The German Einsatzgruppe III entered the city on 12 September.[27] On 16 September, the local German head of administration took over, and afterwards German attacks on local Poles and Jews intensified.[28] Already in September 1939, the Germans carried out first arrests of Poles as part of the Intelligenzaktion and established first prisons for arrested Poles, and in November 1939 the Radogoszcz concentration camp was established, which would be soon converted into the infamous Radogoszcz prison.[29]

Despite plans for the city to become a Polish enclave attached to the General Government, the Nazi hierarchy respected the wishes of many ethnically German residents and of the Reichsgau Wartheland governor Arthur Greiser by annexing the city to Nazi Germany on 9 November 1939. The Germans then destroyed the monument of Polish national hero Tadeusz Kościuszko.[28] As part of the Intelligenzaktion, many Poles arrested in Łódź, Pabianice and other nearby settlements were imprisoned in the Radogoszcz camp and then deported to other German concentration camps or mostly murdered in the forests in the present-day district of Łagiewniki and the nearby village of Lućmierz-Las.[29] Hundreds of Poles were massacred there in late 1939 and early 1940, including teachers, activists, local officials, journalists, lawyers, parliamentarians, etc.[29] Many Germans in the city, however, refused to sign the Volksliste and become Volksdeutsche; they were deported by the General Government. The city was given the new name of "Litzmannstadt" after Karl Litzmann, the German general who had captured it during World War I.

The Nazi authorities soon established the Łódź Ghetto (Ghetto Litzmannstadt) in the city and populated it with more than 200,000 Jews from the Łódź area.[30][31][32][33][34][35] As Jews were deported from Litzmannstadt for extermination, others were brought in.[33][35] The secret Polish Council to Aid Jews "Żegota", established by the Polish resistance movement, operated in the city.[36] Due to the value of the goods that the ghetto population produced for the German military and various civilian contractors, it was the last major ghetto to be liquidated, in August 1944.[35]

Several other German camps arose in the city and its vicinity for non-Jewish people, including a camp for the Romani people deported from abroad, who were soon exterminated at Chełmno,[30][33] a penal "education" forced labour camp in the present-day district of Sikawa,[37] four transit camps for Poles expelled from the city and region, and a racial research camp for expelled Poles.[38] In the latter, Poles were subjected to racial selection before deportation to forced labour in Germany, and Polish children were taken from their parents and sent to Germanisation camps.[39] Most of the children never returned.[39] In 1942–1945, the German Sicherheitspolizei operated a concentration camp for kidnapped Polish children of 2 to 16 years of age in the city.[40] It served as a forced labour camp, penal camp, internment camp and racial research center.[40] The children were subjected to starvation, exhausting labour, beating even up to death and diseases,[30] and the camp was nicknamed "little Auschwitz" due to its conditions.[40] Many children died in the camp.[30]

While occupied, thousands of new ethnic German Volksdeutsche came to Łódź from all across Europe, many of whom were repatriated from Russia during the time of Hitler's alliance with the Soviet Union before Operation Barbarossa. In January 1945, most of the German population fled the city for fear of the Soviet Red Army. The city also suffered tremendous losses due to the German policy of requisition of all factories and machines and transporting them to Germany. Thus, despite relatively small losses due to fighting and aerial bombardment, Łódź was deprived of most of its industrial infrastructure.

Prior to World War II, Łódź's Jewish community numbered around 233,000 and accounted for one-third of the city's total population.[34][41] The community was almost entirely wiped out in the Holocaust.[34][41] By the end of the war, the city and its environs had lost approximately 420,000 of its pre-war inhabitants, including approximately 300,000 Polish Jews.[34][41][42]

On 1 August 1944 the Warsaw Uprising erupted, and the fate of the remaining inhabitants of the Łódź Ghetto was sealed. During the last phase of its existence, some 25,000 inmates were murdered at Chełmno; their bodies burned immediately after death.[43][44] As the front approached, German officials decided to deport the remaining Jews to Auschwitz-Birkenau aboard Holocaust trains. A handful of people were left alive in the ghetto to clean it up.[45] Others remained in hiding with the Polish rescuers.[46] When the Red Army entered Łódź on 19 January 1945, only 877 Jews were still alive, 12 of whom were children.[32] Of the 223,000 Jews in Łódź before the invasion, only 10,000 survived the Holocaust in other places.[41]

The Soviet Red Army entered the city on 18 January 1945. According to Marshal Katukov, whose forces participated in the operation, the Germans retreated so suddenly that they had no time to evacuate or destroy any of the factories, as they had in other cities.[47] Łódź subsequently became part of the Polish People's Republic.

After World War II in the Polish People's Republic[]

At the end of World War II, Łódź had fewer than 300,000 inhabitants. However the number began to grow as refugees from Warsaw and territories annexed by the Soviet Union migrated. Until 1948 the city served as a de facto capital of Poland, since the Warsaw Uprising and the planned destruction of Warsaw by Germany, and most of the government and country administration resided in Łódź. Some planned moving the capital there permanently; however, this idea did not gain popular support and in 1948 the reconstruction of Warsaw began.

Under the Polish Communist regime many of the rich industrialist and business magnate families lost their wealth when the authorities nationalised private companies. Once again the city became a major centre of industry. A number of extensive panel block housing estates (including Retkinia, Teofilów, Widzew, Radogoszcz and Chojny) were constructed between 1960 and 1990, covering an area of almost 30 square kilometres (12 sq mi) and accommodating a large part of the city's population.[48] In mid-1981 Łódź became famous for its massive hunger demonstration of local mothers and their children.[49][50][51] In 1988 the population of the city peaked to 854,261, gradually dropping ever since.[52] After the period of economic transition during the 1990s, most enterprises were again privatised.

Geography[]

Climate[]

Łódź has a humid continental climate (Dfb in the Köppen climate classification).

| Climate data for Łódź, elevation: 68 m (223 ft), 1981–2010 normals, extremes 1951–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 12.8 (55.0) |

17.5 (63.5) |

23.8 (74.8) |

29.9 (85.8) |

32.7 (90.9) |

36.3 (97.3) |

37.3 (99.1) |

37.6 (99.7) |

34.7 (94.5) |

25.9 (78.6) |

19.2 (66.6) |

14.9 (58.8) |

37.6 (99.7) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 0.8 (33.4) |

2.3 (36.1) |

6.9 (44.4) |

13.7 (56.7) |

19.4 (66.9) |

21.8 (71.2) |

24.3 (75.7) |

23.9 (75.0) |

18.4 (65.1) |

12.9 (55.2) |

6.0 (42.8) |

1.7 (35.1) |

12.7 (54.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −1.8 (28.8) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

3.1 (37.6) |

8.6 (47.5) |

13.9 (57.0) |

16.4 (61.5) |

18.8 (65.8) |

18.4 (65.1) |

13.7 (56.7) |

8.9 (48.0) |

3.3 (37.9) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

8.5 (47.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −4.4 (24.1) |

−3.7 (25.3) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

3.5 (38.3) |

8.4 (47.1) |

11.1 (52.0) |

13.2 (55.8) |

12.8 (55.0) |

9.0 (48.2) |

4.9 (40.8) |

0.6 (33.1) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

4.3 (39.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −31.1 (−24.0) |

−27.4 (−17.3) |

−21.9 (−7.4) |

−8.0 (17.6) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

4.2 (39.6) |

3.3 (37.9) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

−9.9 (14.2) |

−16.8 (1.8) |

−24.6 (−12.3) |

−31.1 (−24.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 33.5 (1.32) |

32.1 (1.26) |

37.8 (1.49) |

34.2 (1.35) |

56.9 (2.24) |

63.1 (2.48) |

83.3 (3.28) |

59.3 (2.33) |

47.7 (1.88) |

33.9 (1.33) |

44.6 (1.76) |

43.7 (1.72) |

570.1 (22.44) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 9.0 | 8.2 | 8.5 | 7.2 | 9.0 | 10.0 | 9.7 | 8.1 | 8.1 | 7.6 | 9.3 | 10.0 | 104.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 48.0 | 62.7 | 110.9 | 168.1 | 239.4 | 225.8 | 247.2 | 233.0 | 142.6 | 110.0 | 48.5 | 34.8 | 1,671 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Source 1: meteomodel.pl[53] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: WeatherAtlas[54] | |||||||||||||

Districts[]

Łódź was previously subdivided into five boroughs (dzielnica): Bałuty, Widzew, Śródmieście, Polesie, Górna.

However, the city is now divided into 36 osiedla (districts): Bałuty-Centrum, Bałuty-Doły, Bałuty Zachodnie, Julianów-Marysin-Rogi, Łagiewniki, Radogoszcz, Teofilów-Wielkopolska, Osiedle Wzniesień Łódzkich, Chojny, Chojny-Dąbrowa, Górniak, Nad Nerem, Piastów-Kurak, Rokicie, Ruda, Wiskitno, Osiedle im. Józefa Montwiłła-Mireckiego, Karolew-Retkinia Wschód, Koziny, Lublinek-Pienista, Retkinia Zachód-Smulsko, Stare Polesie, Zdrowie-Mania, Złotno, Śródmieście-Wschód, Osiedle Katedralna, Andrzejów, Dolina Łódki, Mileszki, Nowosolna, Olechów-Janów, Stary Widzew, Stoki, Widzew-Wschód, Zarzew, and Osiedle nr 33.

Demographics[]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1777 | 265 | — |

| 1800 | 428 | +61.5% |

| 1820 | 767 | +79.2% |

| 1830 | 4,343 | +466.2% |

| 1850 | 15,760 | +262.9% |

| 1900 | 314,020 | +1892.5% |

| 1915 | 600,000 | +91.1% |

| 1918 | 341,800 | −43.0% |

| 1931 | 605,500 | +77.2% |

| 1939 | 672,000 | +11.0% |

| 1946 | 496,929 | −26.1% |

| 1950 | 620,273 | +24.8% |

| 1970 | 762,699 | +23.0% |

| 1980 | 835,658 | +9.6% |

| 1988 | 854,003 | +2.2% |

| 1990 | 848,258 | −0.7% |

| 2000 | 793,217 | −6.5% |

| 2010 | 730,633 | −7.9% |

| 2020 | 677,286 | −7.3% |

Łódź was Poland's second largest city until 2007, when it lost its position to Kraków.[55] This is because alongside the entire region of Łódź Voivodeship,[56] the city is experiencing substantial population decline.[57] Since the population peak of 1988, when the number of inhabitants reached 854,261,[52] Łódź has lost almost 180,000 residents. Such a dramatic change results mainly from low fertility rates and lower life expectancy than in other parts of Poland on the one hand, and a negative migration balance on the other.[56] A major factor behind the shrinkage of the city was the transition from socialist to market-based economy after 1989 and the resulting economic crisis,[58] but the economic growth following Poland's accession to the European Union in 2004 has not reversed the trend.[59] The process of suburbanization also contributes to it, with a number of non-urban areas in counties surrounding Łódź steadily increasing in population. While the 'fringe area' around Łódź is expected to register an insignificant growth of less than 2,000 people until 2050, the population of the city proper by the middle of the 21st century is estimated to drop below the level of 500,000.[57] The ongoing ageing and depopulation of Łódź is a major challenge for the future development of the city, putting strain on social infrastructure and medical services.[55]

Łódź has one of the highest feminization rates among Poland's major cities, a legacy of the city's industrial past, when the textile factories attracted large numbers of female employees.[55] The rising age of the population, coupled with a longer life expectancy among women, further exacerbates the disproportion.[55]

Places of interest[]

The most notable and recognizable landmark of the city is Piotrkowska Street, which remains the high-street and main tourist attraction in the city, runs north to south for a little over five kilometres (3.1 miles). This makes it one of the longest commercial streets in the world. Most of the building façades, many of which date back to the 19th century, have been renovated.[60] It is the site of most restaurants, bars and cafes in Łódź's city centre.

Many neglected tenement houses throughout the entire city centre have been renovated in recent years as part of the ongoing revitalization project run by the local authorities.[61] The best example of urban regeneration in Łódź is the Manufaktura complex, occupying a large area of a former cotton factory dating back to the nineteenth century.[62] The site, which was the heart of Izrael Poznański's industrial empire, now hosts a shopping mall, numerous restaurants, 4-star hotel, multiplex cinema, factory museum, bowling and fitness facilities and a science exhibition centre.[63] Opened in 2006, it quickly became a centre of cultural entertainment and shopping,[63] as well as a recognizable city landmark attracting both domestic and foreign tourists.[62] The city is also likely to receive a large boost in terms of tourism once the massive revitalization project of the city's downtown (worth 4 billion PLN) is completed.[9] The local government's efforts to transform the former industrial city into a thriving urban environment and tourist destination formed the basis for the city's failed bid to organise the 2022 International EXPO exhibition on the subject of urban renewal.[64]

Łódź has one of the best museums of modern art in Poland. Muzeum Sztuki has three branches, two of which (ms1 and ms2) display collections of 20th and 21st century art. The newest addition to the museum, ms2 was opened in 2008 in the Manufaktura complex.[65] The unique collection of the Museum is presented in an unconventional way: instead of a chronological lecture on the development of art, works of art representing various periods and movements are arranged into a story touching themes and motifs important for the contemporary public. The third branch of Muzeum Sztuki, located in one of the city's many industrial palaces, also has more traditional art on display, presenting works by European and Polish masters such as Stanisław Wyspiański and Henryk Rodakowski.[66]

Among the 14 registered museums to be found in Łódź,[67] there is the independent Book Art Museum, awarded the American Printing History Association's Institutional Award for 2015 for its outstanding contribution to the study, recording, preservation and dissemination of printing history in Poland over the last 35 years.[68] Other notable museums include the Central Museum of Textiles with its open-air display of wooden architecture, the Cinematography Museum, located in Scheibler Palace, and the Museum of Independence Traditions, occupying the building of a historical Tsarist prison from the late 19th century.[65] A more unusual establishment, the Dętka museum offers tourists a chance to visit the municipal sewer designed in the early years of the 20th century by the British engineer William Heerlein Lindley.

Łódź also provides plenty of green spaces for recreation. Woodland areas cover 9.61% of the city, with parks taking up an additional 2.37% of the area of Łódź (as of 2014).[69] Las Łagiewnicki (Łagiewnicki Forest), the largest forest within city limits, is referred to in scholarship as "the largest forested area within the administrative borders of any city in Europe."[70] It has an area of 1,245 ha[69] and is cut across by a number of hiking trails that traverse the hilly landscape on the western edge of Łódź Hills Landscape Park.[71] A "natural complex which has remained nearly intact as oak-hornbeam and oak woodland,"[70] the forest is also rich in history, and its attractions include a Franciscan friary dating back to the early 18th century and two 17th-century wooden chapels.[72] Out of a total of 44 parks in Łódź (as of 2014), 11 have historical status, the oldest of them dating back to the middle of the 19th century.[73] The largest of these, Józef Piłsudski Park (188,21 ha),[69] is located near the Łódź Zoo and the city's botanical garden, and together with them it comprises an extensive green complex known as Zdrowie serving the recreational needs of the city. Another notable park located in Łódź is the Józef Poniatowski Park.

The Jewish Cemetery at Bracka Street, one of the largest of its kind in Europe, was established in 1892. After the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany in 1939, this cemetery became a part of Łódź's eastern territory known as the enclosed Łódź ghetto (Ghetto Field). Between 1940 and 1944, approximately 43,000 burials took place within the grounds of this rounded-up cemetery.[74] In 1956, a monument by Muszko in memory of the victims of the Łódź Ghetto was erected at the cemetery. It features a smooth obelisk, a menorah, and a broken oak tree with leaves stemming from the tree (symbolizing death, especially death at a young age). As of 2014 the cemetery has an area of 39.6 hectare. It contains approximately 180,000 graves, approximately 65,000 labelled tombstones, ohels and mausoleums. Many of these monuments have significant architectural value; 100 of these have been declared historical monuments and have been in various stages of restoration. The mausoleum of Izrael and Eleanora Poznanski is perhaps the largest Jewish tombstone in the world and the only one decorated with mosaics.[75][76]

Economy and infrastructure[]

Before 1990, the economy of Łódź was heavily reliant on the textile industry, which had developed in the city in the nineteenth century owing to the abundance of rivers used to power the industry's fulling mills, bleaching plants and other machinery.[77] Because of the growth in this industry, the city has sometimes been called the "Polish Manchester"[78] and the "lingerie capital of Poland".[79] As a result, Łódź grew from a population of 13,000 in 1840 to over 500,000 in 1913. By the time right before World War I Łódź had become one of the most densely populated industrial cities in the world, with 13,280 inhabitants per km2, and also one of the most polluted. The textile industry declined dramatically in 1990 and 1991, and no major textile company survives in Łódź today. However, countless small companies still provide a significant output of textiles, mostly for export. Łódź is no longer a significant industrial centre, but it has become a major hub for the business services sector in Poland owing to the availability of highly skilled workers and active cooperation between local universities and the business sector.[80]

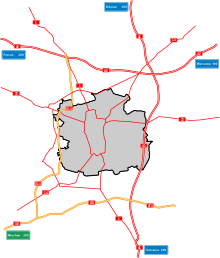

The city benefits from its central location in Poland. A number of firms have located their logistics centres in the vicinity. Two motorways, A1 spanning from the north to the south of Poland, and A2 going from the east to the west, intersect northeast of the city. As of 2012, the A2 is complete to Warsaw and the northern section of A1 is largely completed. With these connections, the advantages of the city's central location should increase even further. Work has also begun on upgrading the railway connection with Warsaw, which reduced the 2-hour travel time to make the 137 km (85 mi) journey 1.5 hours in 2009. As of 2018, travel time from Łódź to Warsaw is around 1.2 hours with the modern Pesa SA Dart trains.[81]

Recent years have seen many foreign companies opening and establishing their offices in Łódź. The Indian IT company Infosys has one of its centres in the city. In January 2009 Dell announced that it will shift production from its plant in Limerick, Ireland to its plant in Łódź, largely because the labour costs in Poland are a fraction of those in Ireland.[82] The city's investor friendly policies have attracted 980 foreign investors by January 2009.[82] Foreign investment was one of the factors which decreased the unemployment rate in Łódź to 6.5 percent in December 2008, from 20 percent four years earlier.[82]

Transport[]

Łódź is situated near the geographical centre of Poland, only a short distance away from the motorway junction in Stryków where the two main north–south (A1) and east–west (A2) Polish transport corridors meet, which positions the city on two of the ten major trans-European routes: from Gdańsk to Žilina and Brno and from Berlin to Moscow via Warsaw.[83] It is also part of the New Silk Road,[84] a regular cargo rail connection with the Chinese city of Chengdu operating since 2013.[85] Łódź is served by the national motorway network, an international airport, and long-distance and regional railways. It is at the centre of a regional and commuter rail network operating from the city's various train stations. Bus and tram services are operated by a municipal public transport company. There are 193 km (120 mi) of bicycle routes throughout the city (as in January 2019).[86]

Major roads include:

- A1: Gdańsk – Toruń – Łódź – Częstochowa – Cieszyn (national border)

- A2: Świecko (national border) – Poznań – Łódź – Warszawa

- S8: Wrocław – Sieradz – Łódź – Piotrków Trybunalski – Warszawa – Białystok

- S14: Pabianice – Konstantynów Łódzki – Aleksandrów Łódzki – Zgierz

- DK14: Łowicz – Stryków – Łódź – Zduńska Wola – Sieradz – Złoczew – Walichnowy

- DK72: Konin – Turek – Poddębice – Łódź – Brzeziny – Rawa Mazowiecka

- DK91: Gdańsk – Tczew – Toruń – Łódź – Piotrków Trybunalski – Radomsko – Częstochowa

Airport[]

The city has an international airport: Łódź Władysław Reymont Airport located 6 kilometres (4 miles) from the city centre. Flights connect the city with destinations in Europe including Turkey.[87] In 2014 the airport handled 253,772 passengers.[88] It is the 8th largest airport in Poland.[89][circular reference]

Public Transport[]

The Municipal Transport Company – Łódź (Miejskie Przedsiębiorstwo Komunikacyjne – Łódź), owned by the Łódź City Government, is responsible for operating 58 bus routes and 19 tram lines.[90][91]

Rail[]

Łódź has a number of long distance and local railway stations. There are two main stations in the city, but with no direct rail connection between them—a legacy of 19th-century railway network planning. Originally constructed in 1866, the centrally-located Łódź Fabryczna was a terminus station for a branch line of the Warsaw-Vienna railway,[92] whereas Łódź Kaliska was built more than thirty years later on the central section of the Warsaw-Kalisz railway. For this reason most intercity train traffic goes to this day through Łódź Kaliska station, despite its relative distance from the city centre, and Łódź Fabryczna serves mainly as a terminal station for trains to Warsaw. The situation will be remedied in 2021 after the construction of a tunnel connecting the two,[93] which is likely to make Łódź Poland's main railway hub.[94] The tunnel will additionally serve Łódź Commuter Railway, providing a rapid transit system for the city, dubbed the Łódź Metro by the media and local authorities.[95] Two new stations are to be constructed on the underground line, one serving the needs of the Manufaktura complex and the other located in the area of Piotrkowska Street.[95]

In December 2016, a few years after the demolition of the old building of Łódź Fabryczna station, a new underground station was opened.[94] It is considered to be the largest and most modern of all train stations in Poland and is designed to handle increased traffic after the construction of the tunnel.[96] It also serves as a multimodal transport hub, featuring an underground intercity bus station, and is integrated with a new transport interchange serving taxis and local trams and buses.[97] The construction of the new Łódź Fabryczna station was part of a broader project of urban renewal known as (New Centre of Łódź).[98]

The third-largest train station in Łódź is Łódź Widzew. There are also many other stations and train stops in the city, many of which were upgraded as part of the Łódzka Kolej Aglomeracyjna commuter rail project. The rail service, founded as part of a major regional rail upgrade and owned by Łódź Voivodeship, operates on routes to Kutno, Sieradz, Skierniewice, Łowicz, and on selected days to Warsaw, with plans for further expansion after the construction of the tunnel.[99]

Education[]

Łódź is a thriving center of academic life. Currently Łódź hosts three major state-owned universities, six higher education establishments operating for more than a half of the century, and a number of smaller schools of higher education. The tertiary institutions with the most students in Łódź include:

- University of Łódź (UŁ - Uniwersytet Łódzki)

- Lodz University of Technology (PŁ - Politechnika Łódzka)

- Medical University of Łódź (Uniwersytet Medyczny w Łodzi)

- National Film School in Łódź (Państwowa Wyższa Szkoła Filmowa, Telewizyjna i Teatralna w Łodzi)

- Academy of Music in Łódź (Akademia Muzyczna im. Grażyny i Kiejstuta Bacewiczów w Łodzi)

- Academy of Fine Arts In Łódź (Akademia Sztuk Pięknych im. Wł. Strzemińskiego w Łodzi)

In the 2018 general ranking of state-owned tertiary education institutions in Poland, the university of Łódź came 20th (6th place among universities) and Lodz University of Technology 12th (6th place among technical universities). The Medical University of Łódź was ranked 5th among Polish medical universities. Leading courses taught in Łódź include administration (UŁ - 3rd place), law (UŁ - 4th place) and biology (UŁ - 4th place).[100]

There is also a number of private-owned institutions of higher learning in Łódź. The largest of these are the University of Social Sciences (Społeczna Akademia Nauk) and the University of Humanities and Economics in Łódź (Akademia Humanistyczno-Ekonomiczna w Łodzi). In the 2018 ranking of private universities in Poland the former was ranked 9th, and the latter 23rd.[100]

National Film School in Łódź[]

Leon Schiller National Higher School of Film, Television and Theatre in Łódź (Państwowa Wyższa Szkoła Filmowa, Telewizyjna i Teatralna im. Leona Schillera w Łodzi) is the most notable academy for future actors, directors, photographers, camera operators and TV staff in Poland. It was founded on 8 March 1948 and was initially planned to be moved to Warsaw as soon as the city was rebuilt following the Warsaw Uprising. However, in the end the school remained in Łódź and today is one of the best-known institutions of higher education in the city.

At the end of the Second World War Łódź remained the only large Polish city besides Kraków which war had not destroyed. The creation of the National Film School gave Łódź a role of greater importance from a cultural viewpoint, which before the war had belonged exclusively to Warsaw and Kraków. Early students of the School include the directors Andrzej Munk, Andrzej Wajda, Kazimierz Karabasz (one of the founders of the so-called Black Series of Polish Documentary) and Janusz Morgenstern, who at the end of the 1950s became famous as one of the founders of the Polish Film School of Cinematography.[101]

Culture[]

Museums in Łódź[]

- Archaeological and Ethnographical Museum

- Book Art Museum

- Central Museum of Textiles

- City of Lodz History Museum

- Film Museum

- Herbst Palace Museum

- Muzeum Sztuki (Museum of Art)

- Natural History Museum, university of Łódź

- Muzeum Tradycji Niepodległościowych (Independence Traditions Museum) with three parts:

- Radegast train station

- Mausoleum and museum in Radogoszcz – Radogoszcz prison

- exhibition Kuźnia Romów (Roma forge) in former Łódź Ghetto

- Se-ma-for museum of stop-motion film animation

- The Centre for Science and Technology EC1 in former Łódź power plant

Łódź in literature and cinema[]

Three major novels depict the development of industrial Łódź: Władysław Reymont's The Promised Land (1898), Joseph Roth's Hotel Savoy (1924) and Israel Joshua Singer's The Brothers Ashkenazi (1937). Roth's novel depicts the city on the eve of a workers' riot in 1919. Reymont's novel was made into a film by Andrzej Wajda in 1975. In the 1990 film Europa Europa, Solomon Perel's family flees pre-World War II Berlin and settles in Łódź. Scenes of David Lynch's 2006 film Inland Empire were shot in Łódź. Paweł Pawlikowski's film Ida was partially shot in Łódź. Sections of Harry Turtledove's Worldwar alternate history series take place in Łódź, and, in John Birmingham's Axis of Time alternate history trilogy, Łódź gains the unfortunate historical notoriety of becoming the first city to be destroyed by an Atomic Bomb when the USSR destroys the city on 5 June 1944.

Sport[]

The city has experience as a host for international sporting events such as the 2009 EuroBasket,[102] the 2011 EuroBasket Women, the 2014 FIVB Volleyball Men's World Championship and the 2019 FIFA U-20 World Cup, with the opening and final of the latter taking place at Stadion Widzewa. Łódź will also host the sixth edition of the European Universities Games in 2022.[103]

Under communism it was common for clubs to participate in many different sports for all ages and sexes. Many of these traditional clubs still survive today. Originally they were owned directly by a public body, but now they are independently operated by clubs or private companies. However they get public support through the cheap rent of land and other subsidies from the city. Some of their sections have gone professional and separated from the clubs as private companies. For example, Budowlani S.A is a private company that owns the only professional rugby team in Łódź, while Klub Sportowy Budowlani remains a community amateur club.

- Budowlani Łódź – rugby (six times Polish champions), hockey, wrestling, volleyball

- ŁKS Łódź – association football (two times Polish champions), basketball (Polish champions 1953), volleyball (two times Polish champions), handball, boxing

- SMS Łódź[104] – association football, volleyball, basketball

- KS Społem Łódź – road and track cycling

- SKS Start Łódź[105] – football, swimming

- Widzew Łódź – association football (four time Polish champions, semi-finalists of the 1982–83 European Cup)

In Ekstraklasa of Polish beach soccer Łódź have three professional clubs: Grembach, KP and .

Horticultural Expo 2029[]

Łódź bid for the Specialized Expo 2022/2023 but lost out to Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Łódź was planned to host the Horticultural Expo in 2024. However, multiple Expo events were delayed due to COVID-19 pandemic, a Horticultural Expo in Doha, Qatar from 2021/22 to 23/24 among them.[106] As a result, the Horticultural Expo in Łódź has been rescheduled to 2029 to maintain a required time interval between them.[107]

International relations[]

Łódź is home to nine foreign consulates, all of which are Honorary. They are subordinate to the following states main representation in Poland: French, Danish, German, Austrian, British, Belgian, Latvian, Hungarian and Moldavian.

Twin towns – sister cities[]

Łódź is twinned with:[108]

|

|

Łódź belongs also to the Eurocities network.

Notable residents[]

- Daniel Amit (1938–2007), Israeli physicist

- Yehuda Ashlag (1885–1954), also known as the Baal Ha-Sulam, Rabbi

- Grażyna Bacewicz (1909–1969), composer

- Aleksander Bardini (1913–1995), theatre director and actor

- Andrzej Bartkowiak (born 1950), cameraman and film director

- Jurek Becker (1937–1997), writer

- Sylwester Bednarek (born 1989), high jumper

- Marek Belka (born 1952), politician, former Prime Minister, Finance Minister of Poland, member European Parliament

- Kazimierz Brandys (1916–2000), writer

- Artur Brauner (1918−2019), film producer

- Edward Gustave Brisch (1901-1960), industrial coding and classification expert. He was the designer of the Brisch Classification, widely known and used in building and engineering.

- Jacob Bronowski (1908–1974), writer, mathematician, and Britain's leading academic TV figure of the 1970s.

- Sabina Citron (born 1928), Holocaust survivor, activist, and author

- Bat-Sheva Dagan (born 1925), Holocaust survivor, teacher, psychologist, author

- Karl Dedecius (1921–2016), translator

- Karl Dominik (born 1980), China's first Chinese speaking Polish actor

- Marek Edelman (1919/1922–2009), Holocaust survivor, one of the leaders of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, Solidarity activist, Polish politician, human rights activist

- Jacob Eisner (born 1947), Israeli basketball player

- Max Factor Sr. (1877–1938), businessman, founder of the Max Factor cosmetics company[129]

- Dov Freiberg (1927–2008), Holocaust survivor and writer

- Joseph Friedenson (1922–2013), Holocaust survivor and writer

- Piotr Fronczewski (born 1946), Polish actor

- Marcin Gortat (born 1984), NBA basketball player for the Washington Wizards

- Mendel Grossman (1913–1945), Łódź ghetto photographer [130]

- Józef Hecht (1891–1951), engraver and printmaker

- Jerzy Janowicz (born 1990), tennis player

- Josef Joffe (born 1944), journalist

- Michał Kalecki (1899–1970), Marxian economist, "one of the most distinguished economists of the 20th century"

- Roman Kantor (1912-1943), épée fencer, Nordic champion and Soviet champion; killed by the Nazis

- Jan Karski (1914–2000), diplomat and anti-nazi resistant

- Aharon Katzir (1914–1972), Israeli pioneer in study of electrochemistry of biopolymers; killed in Lod Airport Massacre

- Lea Koenig (born 1929), Israeli actress

- Paul Klecki (1900–1973), conductor

- Katarzyna Kobro (1898–1951), sculptor

- Jerzy Kosinski (1933–1991), writer

- Jan Kowalewski (1892–1965), cryptologist who broke Soviet military codes, and ciphers during the Polish-Soviet War

- Karolina Kowalkiewicz (born 1985), UFC Strawweight Title challenger

- Feliks W. Kres (born 1966), fantasy writer

- Anna Lewandowska (born 1988), karateka and nutrition expert

- Nathan Lewin, Washington, D.C. attorney

- Daniel Libeskind (born 1946), architect

- Tadeusz Miciński (1873–1918), poet

- Stanisław Mikulski (1929-2014), actor

- Ruth Minsky Sender (born 1926), author and survivor

- Zew Wawa Morejno (1916–2011), Chief Rabbi

- Konstantin Petrovich Nechaev (1883–1946), White movement leader and mercenary commander in China

- Zbigniew Nienacki (1929–1994), writer

- Marek Olędzki (born 1951), archaeologist

- Marian P. Opala (1921–2010), Oklahoma Supreme Court Justice

- Adam Ostrowski (born 1980), better known as O.S.T.R., rapper

- Władysław Pasikowski (born 1959), film director

- Roman Polanski (born 1933), cinema director, Oscar and Golden Palm winner

- Piotr Pustelnik (born 1951), alpine and high-altitude climber, the 20th man to climb all 14 eight-thousanders.

- Ze'ev Raban (1890–1970), Israeli painter and sculptor

- Władysław Reymont (1867–1925), writer, Nobel Prize winner

- Joseph Rotblat (1908–2005), physicist, Nobel Prize winner

- Stefan Rozental (1903–1994), nuclear physicist

- Artur Rubinstein (1887–1982), pianist

- Arnold Rutkowski, opera singer

- Zbigniew Rybczyński (born 1949), animator and Oscar winner

- Marek Saganowski (born 1978), football player

- Andrzej Sapkowski (born 1948), fantasy writer

- Carl Wilhelm Scheibler (1820–1881), one of the most important Łódź industrialists

- Euzebiusz Smolarek (born 1981), football player

- Piotr Sobociński (1958–2001), cinematographer

- Andrzej Sontag (born 1952), track-and-field star

- Natan Spigel (1900–1942), painter

- Władysław Strzemiński (1893–1952), painter, Katarzyna Kobro's husband

- Arthur Szyk (1894–1951), artist

- Aleksander Tansman (1897–1986), composer and pianist

- Jack Tramiel (1928–2012), computer manufacturer, the founder of Commodore[131]

- Julian Tuwim (1894–1953), poet

- Andrzej Udalski (born 1957), astronomer and astrophysicist

- Miś Uszatek, cartoon character

- Michał Wiśniewski (born 1972), singer

- Paweł Zatorski (born 1990), volleyball player, double World Champion

- Hanna Zdanowska (born 1959), politician

- Aleksandra Ziółkowska-Boehm (born 1949), writer

Gallery of sights[]

Piotrkowska Street - the main promenade of the city

EC1 - former power station, now a museum and planetarium

Manufaktura - once a textile factory, now a shopping centre

Łódź City Hall, formerly Heinzel Palace

International Faculty of Engineering (TUL)

Andel's Hotel Łódź, near Manufaktura shopping mall

Music Academy, formerly Poznański Palace

Red Tower - the former headquarters of mBank

Teodor Steigert's Tenement House

Scheiblers' Tenement House

Herman Konstadt's Tenement House

Mieczysław Pinkus and Jakub Lende's Tenement House

Karl Scheibler's Chapel in Old Cemetery

Workers' houses (famuły) at Księży Młyn

Łódź Special Economic Zone

Gutenberg House

Polonia Palast Hotel

Church of the Assumption of Blessed Virgin Mary

Poniatowski's Park

Botanical Garden in Łódź

Archeological and Ethnographic Museum

Mural in city centre

See also[]

References[]

Notes[]

Citations[]

- ^ a b "Local Data Bank". Statistics Poland. Retrieved 21 June 2020. Data for territorial unit 1061000.

- ^ "Łódź" (US) and "Łódź". Oxford Dictionaries UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- ^ "Lodz". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- ^ "Łódź". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- ^ "Łódź". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- ^ "Łódź - Warszawa trasa i odległość na mapie • dojazd PKP, BUS, PKS". www.trasa.info. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ^ a b "Lodz – Tourism | Tourist Information – Lodz, Poland". staypoland.com. eTravel S.A.

- ^ Cysek-Pawlak, Monika; Krzysztofik, Sylwia (2017). "Integrated Approach as a Means of Leading the Degraded Post-Industrial Areas Out of Crisis - A Case Study of Lodz". IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. 245 (8): 082036. Bibcode:2017MS&E..245h2036C. doi:10.1088/1757-899X/245/8/082036. eISSN 1757-899X. ISSN 1757-8981.

- ^ a b “4 Billion PLN for Revitalization of Downtown Łódź.” lodzpost.com. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ^ "The World According to GaWC 2020". GaWC - Research Network. Globalization and World Cities. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- ^ "Poland’s Łódź named UNESCO City of Film." Radio Poland. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- ^ "German Łódź". Centrum Dialogu (Dialog Center). Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- ^ a b c Wiesław Puś, Stefan Pytlas. "Industry and Trade in Łódź and the Eastern Markets in Partitioned Poland". In: Uwe Müller, Helga Schultz. National borders and economic disintegration in modern East Central Europe. Berlin Verlag A. Spitz. 2002. p. 69.

- ^ Włodzimierz Borodziej. "Nachbarn, Fremde, Okkupanten: Die Deutschen im unabhängigen und besetzten Polen (1919-44)". Als der Osten noch Heimat war. Rowohls Taschenbuch Verlag.

- ^ "Neues Leben in alten Fabriken: Lódz baut auf Kultur" (in German). Weser Kurier. 22 September 2009. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- ^ "Foundation For Saving Karol Scheibler's Chapel". Scheibler.org.pl. Archived from the original on 11 January 2010. Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- ^ Adam Leszczyński. Ludowa historia Polski. Warszawa 2020. p. 354, 356-359.

- ^ "Russia: Principal Towns". Statesman's Year-Book. London: Macmillan and Co. 1898. p. 863. hdl:2027/njp.32101020157267.

- ^ Joshua D. Zimmerman, Poles, Jews, and the Politics of Nationality, Univ of Wisconsin Press, 2004, ISBN 0-299-19464-7, Google Print, p.16

- ^ Witold Iwańczak. "Pionierzy polskiej kinematografii". Niedziela.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ Robert Bubczyk. A History of Poland in Outline. Maria Curie-Skłodowska University Press. 2002. p. 68.

- ^ Geoffrey Jukes, Peter Simkins, Michael Hickey, The First World War: The Eastern Front, 1914–1918, 2002, p. 28

- ^ Gilbert, Martin (1994). The First World War: A Complete History. New York: Henry Holt and Company. p. 107. ISBN 080501540X.

- ^ Alan D. Axelrod, The Complete Idiot's Guide to World War I, 2001, p. 108

- ^ Gordon J Horwitz. Ghettostadt: Łódź and the Making of a Nazi City. Harvard University Press. 2009. p. 3.

- ^ a b John Radzilowski; C. Peter Chen, Invasion of Poland: 1 Sep 1939 – 6 Oct 1939, ww2db.com, retrieved 17 February 2008

- ^ Wardzyńska, Maria (2009). Był rok 1939. Operacja niemieckiej policji bezpieczeństwa w Polsce. Intelligenzaktion (in Polish). Warszawa: IPN. p. 114.

- ^ a b Tomasz Walkiewicz. "Wybuch wojny i początki okupacji hitlerowskiej w Łodzi". Archiwum Państwowe w Łodzi (in Polish). Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ a b c Wardzyńska, Maria (2009). Był rok 1939. Operacja niemieckiej policji bezpieczeństwa w Polsce. Intelligenzaktion (in Polish). Warszawa: IPN. pp. 203–205.

- ^ a b c d Biuletyn Informacyjny Obchodów 60. Rocznicy Likwidacji Litzmannstadt Getto. Nr 1-2. "The establishment of Litzmannstadt Ghetto", Torah Code website. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- ^ Isaiah Trunk: 2006, Page xi

- ^ a b Jennifer Rosenberg (1998). "The Łódź Ghetto". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- ^ a b c Jennifer Rosenberg (2015) [1998]. "The Lódz Ghetto (1939–1945)" (Reprinted with permission). History & Overview. Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- ^ a b c d Jennifer Rosenberg (2006). "The Łódź Ghetto". Part 1 of 2. 20th Century History, About.com. Archived from the original (Internet Archive) on 30 April 2006. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

Lodz Ghetto: Inside a Community Under Siege by Adelson, Alan and Robert Lapides (ed.), New York, 1989; The Documents of the Łódź Ghetto: An Inventory of the Nachman Zonabend Collection by Web, Marek (ed.), New York, 1988; The Holocaust: The Fate of European Jewry by Yahil, Leni, New York, 1991.

- ^ a b c The statistical data, compiled on the basis of "Glossary of 2,077 Jewish towns in Poland" Archived 8 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine by Virtual Shtetl, Museum of the History of the Polish Jews, as well as "Getta Żydowskie" by Gedeon (in Polish) and "Ghetto List" by Michael Peters (in English). Accessed 25 March 2015.

- ^ Datner, Szymon (1968). Las sprawiedliwych (in Polish). Warszawa: Książka i Wiedza. p. 69.

- ^ Wardzyńska, Maria (2009). "Obozy niemieckie na okupowanych terenach polskich". Biuletyn Instytutu Pamięci Narodowej (in Polish). No. 4 (99). IPN. p. 30. ISSN 1641-9561.

- ^ Ledniowski, Krzysztof; Gola, Beata (2020). "Niemiecki obóz dla małoletnich Polaków w Łodzi przy ul. Przemysłowej". In Kostkiewicz, Janina (ed.). Zbrodnia bez kary... Eksterminacja i cierpienie polskich dzieci pod okupacją niemiecką (1939–1945) (in Polish). Kraków: Uniwersytet Jagielloński, Biblioteka Jagiellońska. pp. 148–149.

- ^ a b Ledniowski, Gola, p. 149

- ^ a b c Ledniowski, Gola, p. 147

- ^ a b c d Abraham J. Peck (1997). "The Agony of the Łódź Ghetto, 1941–1944". The Chronicle of the Łódź Ghetto, 1941��1944 by Lucjan Dobroszycki, and The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington D.C. The Simon Wiesenthal Center. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ Weiner, Rebecca. Lodz, Poland Jewish History Tour, Jewish Virtual Library, . Retrieved on 15 January 2008.

- ^ Golden, Juliet (2006). "Remembering Chelmno". In Vitelli, Karen D.; Colwell-Chanthaphonh, Chip (eds.). Archeological Ethics (2nd ed.). AltaMira Press. p. 189. ISBN 075910963X. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ JVL (2013). "Chelmno (Kulmhof)". The Forgotten Camps. Jewish Virtual Library.org. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ S.J., H.E.A.R.T (2007). "Chronicle: 1940 – 1944". The Łódź Ghetto. Holocaust Research Project.org. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ Archives (2015). "Polish Righteous". Łódź. POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ Blobaum, Robert. "On Strike on Łódź. "Rewolucja: Russian Poland, 1904–1907". Cornell University Press, 1995. p. 75.

- ^ Kłysik, Kazimierz (1998). "Charakterystyka powierzchni miejskich Łodzi z klimatologicznego punktu widzenia" (PDF). Folia Geographica Physica. 3: 173–85. ISSN 1427-9711. Retrieved 27 July 2017. (p. 175)

- ^ Ash, Timothy Garton (1 January 1999). The Polish Revolution: Solidarity. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300095686 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Polish Minister and Union Reach Compromise on Meat Ration Cut", By James M. Markham, special to The New York Times: "Three more days of limited protests are planned in Lodz, which appears to have suffered especially from meat shortages."

- ^ Kenney, Padraic (1997). Rebuilding Poland: Workers and Communists 1945-1950. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. p. 342. ISBN 0-8014-3287-1.

- ^ a b Obraniak, Włodzimierz (2007). Ludność Łodzi i innych wielkich miast w Polsce w latach 1984-2006 (PDF). Łódź: Urząd Statystyczny w Łodzi. p. 5. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ^ "Łódź Średnie i sumy miesięczne". meteomodel.pl. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ^ "Monthly weather forecast and Climate – Lodz, Poland". Weather Atlas. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ^ a b c d Cudny, Waldemar (2012). "Socio-Economic Changes in Lodz – The Result of Twenty Years of System Transformation" (PDF). Geografický časopis (Geographical Journal). 64 (1): 3–27. ISSN 1335-1257. Retrieved 25 November 2017. (pp. 11–12).

- ^ a b Szukalski, Piotr; Martinez-Fernandez, Cristina; Weyman, Tamara (2013). "Lódzkie Region: Demographic Challenges Within an Ideal Location". OECD Local Economic and Employment Development (LEED) Working Papers (5/2013): 1–56. doi:10.1787/5k4818gt720p-en. eISSN 2079-4797. hdl:11089/5816. Retrieved 25 November 2017. (p. 7).

- ^ a b Gołata, Elżbieta; Kuropka, Ireneusz (2016). "Large cities in Poland in face of demographic changes". Bulletin of Geography. Socio–Economic Series. 34 (34): 17–31. doi:10.1515/bog-2016-0032. ISSN 1732-4254. Retrieved 25 November 2017. (p. 21).

- ^ Cox, Wendell (2014). "International Shrinking Cities: Analysis, Classification, and Prospects". In Richardson, Harry W.; Nam, Chang Woon (eds.). Shrinking Cities: A Global Perspective. London and New York: Routledge. pp. 11–27. ISBN 978-0415643962. (p.14).

- ^ Holm, Andrej; Marcińczak, Szymon; Ogrodowczyk, Agnieszka (2015). "New-Build Gentrification in the Post-Socialist City: Łódź and Leipzig Two Decades After Socialism" (PDF). Geografie. 120 (2): 164–187. doi:10.37040/geografie2015120020164. ISSN 1212-0014. Retrieved 25 November 2017. (pp. 169–170).

- ^ “Piotrkowska Street Stroll.” Poland's Official Travel Website. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ^ Krakowiak, Beata (2015). "Museums in Łódź as an Element of Tourism Space and the Connection Between Museums and the City's Tourism Image". Tourism. 25 (2): 87–96. doi:10.1515/tour-2015-0008. eISSN 2080-6922. ISSN 0867-5856. Retrieved 18 July 2017. (p. 93).

- ^ a b Kaczmarek, Sylwia; Marcinczak, Szymon (2013). "The Blessing in Disguise: Urban Regeneration in Poland in a Neo-Liberal Milieu". In Leary, Michael E.; McCarthy, John (eds.). The Routledge Companion to Urban Regeneration. Routledge. pp. 98–106. ISBN 978-0-415-53904-3. (p. 103).

- ^ a b Strumiłło, Krystyna (2016). "Adaptive Reuse of Buildings as an Important Factor of Sustainable Development". In Charytonowicz, Jerzy (ed.). Advances in Human Factors and Sustainable Infrastructure. Springer. pp. 51–59. ISBN 978-3-319-41940-4. (p. 56).

- ^ “Poland to invest in Łódź despite failed bid for Expo 2022.” Radio Poland. 16 November 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- ^ a b Krakowiak, p. 88.

- ^ Krakowiak, p 91.

- ^ Krakowiak, p. 88. Krakowiak also lists 13 more institutions that operate as museums but are not registered with the National Institute for Museums and Public Collections (p. 95), bringing the total number of museums in Łódź to 27.

- ^ “Discover the Book Art Museum, Łódź, Poland.” AEPM: Association of European Printing Museums. January 2015. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ^ a b c Długoński, Andrzej; Szumański, Marek (2015). "Analysis of Green Infrastructure in Lodz, Poland". Journal of Urban Planning and Development. 141 (3): n. pag. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)UP.1943-5444.0000242. eISSN 1943-5444. ISSN 0733-9488. Article first published online in 2014.

- ^ a b Jaskulski, Marcin; Szmidt, Aleksander (2015). "The Tourism Attractiveness of Landforms in Łagiewnicki Forest, Łódź". Tourism. 25 (2): 27–35. doi:10.1515/tour-2015-0003. eISSN 2080-6922. ISSN 0867-5856. Retrieved 28 July 2017. (p. 27)

- ^ See Jaskulski and Szmidt, p. 29, for a map of tourism trails in the forest.

- ^ Grzegorczyk, Arkadiusz, ed. (2015). Ilustrowana Encyklopedia Historii Łodzi. Łódź. pp. 59–61. ISBN 978-83-939822-0-2.

- ^ Kaniewska, Anna. “Najstarsze łódzkie parki. Archiwum Państwowe w Łodzi. [The State Archive in Łódź]. 3 April 2009. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ^ "Jewish Lodz Cemetery - About Cemetery At Bracka Street". Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- ^ "The New Cemetery in Łódź". Lodz ShtetLinks. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- ^ "JEWISH CEMETERY". FUNDACJA MONUMENTUM IUDAICUM LODZENSE. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- ^ Kobojek, Elżbieta (2017). "A Small River Within the Urban Space: the Evolution of the Relationship Using the Example of Łódź" (PDF). Space-Society-Economy. 19 (19): 7–20. doi:10.18778/1733-3180.19.01. ISSN 1733-3180. Retrieved 13 July 2018. (p. 10).

- ^ Lamprecht, Mariusz (2014). "Fluctuations in the Development of Cities. A Case Study of Lodz". Studia Regionalia. 38: 77–91. ISSN 0860-3375. Retrieved 13 July 2018. (p. 82).

- ^ Cormier, Amanda (25 December 2019). "The Best Bras Might Be Made in Poland". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- ^ Association of Business Service Leaders (ABSL) (2019). Business Services Sector in Poland 2019 (PDF) (Report). ABSL. pp. 28, 55.

- ^ "Pociągi Łódź – Warszawa - GoEuro". www.goeuro.pl. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ^ a b c (AFP)–24 Jan 2009 (24 January 2009). "AFP: Dell seeks refuge in Poland as crisis bites". Archived from the original on 25 May 2012. Retrieved 11 April 2010.

- ^ Wiśniewski, Szymon (2017). "Łódź in the Regional and National Transportation System" (PDF). Space-Society-Economy. 19 (19): 65–86. doi:10.18778/1733-3180.19.04. ISSN 1733-3180. Retrieved 17 July 2018. p. 66.

- ^ Shepard, Wade (10 November 2016). "Europe Finally Wakes Up To The New Silk Road, And This Could Be Big". Forbes. Retrieved 22 July 2018.

- ^ Bentyn, Zbigniew (2016). "Poland as a Regional Logistic Hub Serving the Development of the Northern Corridor of the New Silk Route". Journal of Management, Marketing and Logistics. 3 (2): 135–44. ISSN 2148-6670. Retrieved 20 July 2018. (p. 142).

- ^ "Statystyki rowerówek" [Bike roads statistics]. rowerowalodz.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on 15 August 2019. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ www.lifemotion.pl. "Our destinations – Port Lotniczy Łódź im. Władysława Reymonta". lodz.pl.

- ^ Wiśniewski, p. 79.

- ^ Statistic taken from the Łódź Władysław Reymont Airport Wikipedia article on 19 July 2015.

- ^ Sourced from the Łódź article on the Polish Wikipedia site on 19 July 2015

- ^ "About MPK – MPK-Lodz Spolka z o.o." lodz.pl.

- ^ Grzegorczyk, p. 144.

- ^ "Łódź railway tunnel tender announced". RailwayPro. 6 December 2016. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ^ a b "Superdworzec już jest, będzie (prawie) metro. Łódź ma być komunikacyjnym centrum kraju". TVN24. 2 December 2016. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ^ a b "Łódź będzie miała 'metro'. I to już niedługo". Wyborcza.pl: Magazyn Łódź. 18 May 2016. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ^ Rogaczewska, Beata (1 November 2016). "Łódź Fabryczna: największy podziemny dworzec kolejowy w Polsce i trzeci w Europie". rp.pl. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ^ Kozlowski, Remigiusz; Palczewska, Anna; Jablonski, Jakub (2016). "The Scope and Capabilities of ITS – The Case of Łódź". In Mikulski, Jerzy (ed.). Challenge of Transport Telematics. Springer. pp. 305–16. ISBN 9783319496450. (p. 308)

- ^ "The New Centre of Łódź has a Local Action Plan – URBACT". urbact.eu.

- ^ "Rekordowy rok Łódzkiej Kolei Aglomeracyjnej". kurierkolejowy.eu. 22 December 2016. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ^ a b Perspektywy University Ranking 2018. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- ^ Dana, Przemek (16 January 2015). "Janusz Morgenstern, reżyser m.in. "Stawki większej niż życie" nie żyje". Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ^ 2009 EuroBasket, ARCHIVE.FIBA.com, Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- ^ Pavitt, Michael (13 April 2018). "Poland and Hungary awarded upcoming editions of European Universities Games". insidethegames.biz. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ "Szkoła Mistrzostwa Sportowego im. K. Górskiego w Łodzi – Oficjalna strona internetowa Szkoły Mistrzostwa Sportowego w Łodzi". smslodz.pl.

- ^ "Spółdzielczy Klub Sportowy START Łódź ul. św. Teresy 56/58 – Oficjalny serwis". sksstart.com.

- ^ "Expo 2021 Doha". Bureau International des Expositions. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

The Government of the State of Qatar has formally requested BIE approval to change the opening dates of Expo 2021 Doha to 2 October 2023 - 28 March 2024. The request follows in depth discussions [...] on the global impact of the Covid-19 pandemic. The Executive Committee of the BIE unanimously agreed to propose the postponement of Horticultural Expo 2021 Doha, with the BIE General Assembly to vote on the recommendation during its next meeting on 1 December 2020.

- ^ "Rok 2029: nowy termin Zielonego Expo w Łodzi" (in Polish). Urząd Miasta Łodzi. 23 September 2020. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ^ "Twin Cities". The City of Łódź Office (in Polish and English). 2007. Archived from the original on 5 October 2013. Retrieved 23 October 2008.

- ^ "Chemnitz". Urząd Miasta Łodzi (in Polish). Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ^ "Stuttgart Städtepartnerschaften". Landeshauptstadt Stuttgart, Abteilung Außenbeziehungen (in German). Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- ^ "Partner Cities of Lyon and Greater Lyon". Mairie de Lyon. 2008. Archived from the original on 19 July 2009. Retrieved 21 October 2008.

- ^ "Wilno". Urząd Miasta Łodzi (in Polish). Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ^ "Wilno" (PDF). bip.uml.lodz.pl. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ^ "Kaliningrad -Partner Cities". Kaliningrad City Hall. 2000. Archived from the original on 22 April 2009. Retrieved 8 December 2008.

- ^ "Twin towns and Sister cities of Minsk [via WaybackMachine.com]" (in Russian). The department of protocol and international relations of Minsk City Executive Committee. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- ^ "Porozumienie o ustanowieniu braterskich więzi między miastami Łódź (Polska) i Odessa (Ukraina)" [Agreement to establish fraternal ties between cities of Łódź (Poland) and Odessa (Ukraine)] (PDF). uml.lodz.pl (in Polish and Russian). 7 May 1993. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ^ "Odessa". Urząd Miasta Łodzi (in Polish). Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ^ "Tel Aviv sister cities" (in Hebrew). Tel Aviv-Yafo Municipality. Archived from the original on 14 February 2009. Retrieved 19 January 2008.

- ^ "Tjanjin". Urząd Miasta Łodzi (in Polish). Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ^ "Rustawi". Urząd Miasta Łodzi (in Polish). Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ^ "Uchwała XXIV/275/95 Rady Miejskiej w Łodzi" [The City Council resolution No. XXIV/275/95] (PDF). uml.lodz.pl (in Polish). 27 December 1995. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ^ "Barreiro". Urząd Miasta Łodzi (in Polish). Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ^ "Tampere". Urząd Miasta Łodzi (in Polish). Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ^ "Puebla". Urząd Miasta Łodzi (in Polish). Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ^ "Murcia". Urząd Miasta Łodzi (in Polish). Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ^ Vänorter – orebro.se Archived 27 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Lwów". Urząd Miasta Łodzi (in Polish). Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ^ "Szeged". Urząd Miasta Łodzi (in Polish). Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ^ "Max Factor - Lodz". Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- ^ Shapiro, Robert Moses (May 1999). Holocaust chronicles... – Google Books. ISBN 978-0-88125-630-7. Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- ^ "Jack Tramiel, founder of Commodore computers, Lodz survivor, dies at 83 - j. the Jewish news weekly of Northern California". 20 April 2012. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

Bibliography[]

- Alan Adelson and Robert Lapides, Łódź Ghetto : A Community History Told in Diaries, Journals, and Documents, Viking, 1989. ISBN 0-670-82983-8

- "A Stairwell in Lodz," Constance Cappel, 2004, Xlibris, (in English).[self-published source]

- Horwitz, Gordon J. (2009). Ghettostadt: Łódź and the making of a Nazi city. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 27, 54–55, 62. ISBN 978-0674038790. Retrieved 21 March 2015 – via Google Book, preview.

- "Lodz – The Last Ghetto in Poland," Michal Unger, Yad Vashem, 600 pages (in Hebrew)

- Stefański, Krzysztof (2000). Gmachy użyteczności publicznej dawnej Łodzi, Łódź 2000 ISBN 83-86699-45-0.

- Stefański, Krzysztof (2009). Ludzie którzy zbudowali Łódź Leksykon architektów i budowniczych miasta (do 1939 roku), Łódź 2009 ISBN 978-83-61253-44-0.

- Trunk, Isaiah; Shapiro, Robert Moses (2006). Łódź Ghetto: a history. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, Indiana. ISBN 978-0-253-34755-8. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- Trunk, Isaiah; Shapiro, Robert Moses (2008) [2006]. Łódź Ghetto: A History. Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0253347558. Retrieved 29 September 2015 – via Google Book, preview.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Łódź. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Łódź. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Lodz . |

- Łódź

- Cities and towns in Łódź Voivodeship

- City counties of Poland

- Holocaust locations in Poland

- Łódź Voivodeship (1919–1939)

- Magdeburg rights

- Piotrków Governorate