Poland in the European Union

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2017) |

| |

Poland |

EU |

|---|---|

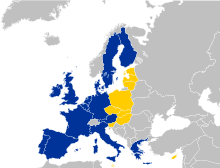

Poland has been a member state of the European Union since 1 May 2004, with the Treaty of Accession 2003 signed on 16 April 2003 in Athens as the legal basis for Poland's accession to the EU. The actual process of integrating Poland into the EU began with Poland's application for membership in Athens on 8 April 1994, and then the confirmation of the application by all member states in Essen from 9–10 December 1994. Poland's integration into the European Union is a dynamic and continuously ongoing process.

Comparison[]

| Population | 447,206,135[1] | 38,386,000 |

| Area | 4,324,782 km2 (1,669,808 sq mi)[2] | 312,696 km2 (120,733 sq mi) |

| Population Density | 115/km2 (300/sq mi) | 123/km2 (318.6/sq mi) |

| Capital | Brussels (de facto) | Warsaw |

| Global Cities | Paris, Rome, Berlin, Vienna, Madrid, Amsterdam, Athens, Dublin, Helsinki, Warsaw, Lisbon, Stockholm, Copenhagen, Praha, Bucharest, Nicosia, Budapest, Zagreb, Sofia | Kraków, Poznań, Gdańsk, Wrocław, Łódź, Białystok, Olsztyn, Lublin, Gdynia |

| Government | Supranational parliamentary democracy based on the European treaties[3] | Unitary semi-presidential

constitutional republic |

| First Leader | High Authority President Jean Monnet | President Wojciech Jaruzelski |

| Current Leader | Council President Charles Michel Commission President Ursula von der Leyen |

President Andrzej Duda Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki |

| Official languages | 24 official languages, of which 3 considered "procedural" (English, French and German)[4] | Polish |

| Main Religions | 72% Christianity (48% Roman Catholicism, 12% Protestantism, 8% Eastern Orthodoxy, 4% Other Christianity), 23% non-Religious, 3% Other, 2% Islam |

92.9% Roman Catholic, 1.3% Other faiths, 3.1% Irreligious, 2.7% Unanswered |

| Ethnic groups | Germans (ca. 80 million), French (ca. 67 million), Italians (ca. 60 million), Spanish (ca. 47 million), Poles (ca. 46 million), Romanians (ca. 16 million), Dutch (ca. 13 million), Greeks (ca. 11 million), Portuguese (ca. 11 million), and others |

98% Polish, 2% others or not stated |

| GDP (nominal) | $16.477 trillion, $31,801 per capita | $607 billion, $15,988 per capita |

Early relations between Poland and the EU (1988–1993)[]

Diplomatic relations between Poland and the European Economic Community began on 16 September 1988. A year later, on 19 September 1989, during the first visit of the Chairman of the Committee of Ministers of the EEC to Poland, an agreement was signed on trade and commercial and economic cooperation in Warsaw.

Changes in Polish politics during and after 1989 allowed diplomatic talks regarding Poland's participation in the European Economic Community. Formal negotiations began on 22 December 1990, and ended on 16 December 1991, in the "". At the same time, along with the European Agreement, Poland signed a trade agreement included in the Interim Agreement in force from 1 March 1992.

Poland's agreement with the EEC came into force on 1 February 1994, three months after the Maastricht Treaty came into effect. The first step was the establishment of the Commission for the Unification of the Republic of Poland with the EU, whose task was to supervise the implementation of the new agreements. Talks at ministerial levels in the Polish Parliament were conducted within this commission. The Parliamentary Unification Committee acted as a forum for relations between the Polish Parliament and the European Parliament.

Nearing accession (1993–1997)[]

Even before accession negotiations began in June 1993, during a meeting of the European Council in Copenhagen, the EU Member States officially confirmed that the countries of Central and Eastern Europe, currently affiliated with the EC, will join the EU after fulfilling economic and political criteria. On 8 April 1994, the Government of the Republic of Poland made a formal request, in Athens, for membership in the European Union. During the European Council summit held in Essen on 9–10 December 1994, Member States adopted a pre-accession strategy, defining the areas and forms of cooperation recognized by the EU as essential to speed up integration. This process also confirmed that the EU was willing to go through with enlargement to associated countries. Formal confirmation of the strategy outlined in the White Paper (on the alignment of countries with the requirements of the internal free-market) which was adopted at the European Council Summit in Cannes in June 1995. The White Paper, and the annual preparatory programs adopted by the Polish government, determined the framework and the relations of Poland with the EU. On 3 October 1996, under the resolution passed by the Council of Ministers on 26 January 1991, the came into force with its purpose to coordinate and assist all ministries and institutions directly involved in the process of Polish integration with the European Union. The primary role of the was to ensure the implementation of the tasks related to coordinating policies on matters related to the integration of Poland into the European Union. Additionally, it was responsible for coordination of measures for the adaptation of Poland to meet European standards, as well as managing the foreign aid that Poland received from the European Union.

In January 1997 Poland adopted the National Strategy for Integration (NSI) which was passed by Parliament in May 1997. The NSI set out the specific tasks that Poland faced on the road to full EU membership and the sequence of their implementation. The NSI's role was, primarily, to accelerate and direct the work of government institutions as well as helping raise societal awareness of the possible consequences of Polish membership in the EU. The adaptation operations for membership were carried out in-line with the National Programme of Preparation for Membership in the European Union (NPPC) framework developed by the government and accepted on 23 June 1998. NPPC was annually (up to and including 2001) modified to conform with the negotiation strategies of the Polish government. It defined the ways in which to achieve the priorities contained in the Partnership for Membership document. Partnership for Membership and the National Programme of Preparation for Membership in the European Union were directly related to the European Commission's decision to provide EU funding through Phare, SAPARD and ISPA, being the three financial instruments of the European Union to assist the candidate countries in the preparation for accession.

Negotiations (1997–2002)[]

On the basis of the recommendations contained in the opinions of the European Commission of 16 July 1997 the European Council meeting in Luxembourg on 12–13 December 1997 decided to begin accession negotiations with five countries of Central and Eastern Europe (Poland, Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovenia and Estonia) as well as Cyprus. For all the Central and Eastern European candidate countries, the European Council launched an enhanced pre-accession strategy, including the implementation of the European Agreements, Partnership for Membership and a new version of the PHARE program .

The EU enlargement process was formally launched at a meeting of the Council for General Affairs on 30 March 1998. At the time, Poland declared 31 December 2002 as the date of readiness for membership into the European Union. A study of the compatibility of candidate countries' current laws with EU law began on 31 March 1998 in Brussels. After the end of the study, the actual negotiations were undertaken at the same time at the request of the candidate countries, although individually with each of the candidates from 10 November 1998. From 16 April 1999, regular meetings of political directors and European correspondents of associated and EU countries began undertaking political dialogue. For the purpose of the negotiations, the EU set up 37 task forces that were responsible for developing agreements in their respective areas. The chairmen of the Polish Negotiation Team (PZN) were, successively: Jacek Saryusz-Wolski (1997-2001) and Danuta Hübner (2001-2004).

The main role of the negotiations was to develop a common position between the Chairman of the PZN and the EU Commissioner for Enlargement and submitting it for approval to the European Commission, which prepared the draft of the revised common position of the whole EU to be accepted by the 15 member states in the European Council. The aim of the negotiations was to prepare the accession treaty, which was adopted at the last meeting of the Intergovernmental Conference on Accession.

In October 1990 it was decided to connect the capitals of the countries associated with the Secretariat of the Council of the EU with the help of a specially prepared communications network. By 2000, Poland managed to finish talks in 25 out of 30 negotiation areas and for 9 of them it was able to agree transition periods. The remaining 5 areas were negotiated between 2001 and 2002.

Polish negotiations with the EU ended during the EU summit in Copenhagen, on 13 December 2002.

Accession (2003–2004)[]

This section does not cite any sources. (July 2017) |

The Treaty of Accession was subject to approval and adoption by an absolute majority vote in the European Parliament on 9 April 2003 and unanimously by the Council of the European Union on 14 April 2003. The next stage was ratification of the treaty by all the member countries in accordance with their constitutional requirements (except for Ireland, where it was ratified after a nationwide referendum while the other Member States adopted it in the form of a parliamentary vote). The Treaty entered into force after the EU ratification procedure. In Poland, the final process of its adoption took place in the form of a national referendum on 7–8 June 2003.

Poles answered the following question:

"Do you give permission for the Republic of Poland to enter into the European Union?"

The National Electoral Commission's published results state that 58.85% of eligible voters turned up to vote (i.e. 17 586 215 out of 29 868 474 people), 77.45% of those (i.e. 13 516 612) answered yes to the question. 22.55% of those (i.e. 3 936 012) answered no. The results also showed that 126 194 votes were deemed to be invalid.

The Treaty of Accession 2003 signed on the 16 April 2003 in Athens was the legal basis for 10 countries Central and Southern Europe (Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Polish, Slovakia, Slovenia and Hungary) entering the European Union.

On 1 May 2004 Poland became a full member of the European Union, along with 9 other European countries.

| EU Member countries | Date of accession |

|---|---|

| Cyprus Czech Republic Estonia Hungary Lithuania Latvia Malta Poland Slovakia Slovenia |

Post-accession (2004–present)[]

According to information provided by the Ministry of Finance (on 8 February 2006), Poland had to be ready to join the eurozone by 2009, however, this was postponed to at least 2018. The Minister of Finance announced a regulation that, as of 15 April 2004, a consumer or a recipient of services is able to pay for their goods or services using euros.

On 13 December 2007, the Reform Treaty was signed by representatives of the 27 EU Member States in the Jeronimos Monastery in Lisbon. On behalf of Poland, the Treaty was signed by Prime Minister Donald Tusk and Foreign Minister Radoslaw Sikorski. At the head of the Polish delegation was President Lech Kaczynski, who was accompanied by the ministers of the Presidential Chancellery: Robert Draba and Michal Kaminski.

Polish accession to the Schengen Agreement took place on 21 December 2007 (for land and sea crossings) and 29 March 2008 (for airports, together with the new flight timetable). On 30 July 2007, Poland passed the technical tests for access to the Schengen system. As proposed by Portugal, a symbolic opening of the borders took place on 21 December 2007 in Worek Turoszowski on the tri-boundary of the Polish, Czech and German borders.

On 1 May 2009, five years after Poland had accessed the European Union, the period of protection against the purchase of homes and apartments in Poland by foreigners (citizens of the EU) had ended.

According to the survey conducted by the Public Opinion Research Centre in March 2014, the Polish presence in the European Union was supported by 89% of Poles, while 7% opposed Poland's EU membership.

The most up-to-date statistics (as of July 2016) show that in 2014 Poland received €17.436 billion from the EU whilst only contributing €3.526 billion.[5] Poland also received nearly €2 billion more in EU funding than any other member state in 2013 (France being second highest).[6] The European Union has made its funding available for infrastructure and transport; agriculture and rural development; health and research; growth and jobs; environment and energy as well as other projects in the European Social Fund. Examples include funding more than 60% of the investment needed to build a section of the A1 motorway between Toruń and Łódź (€1.3 billion), better public transport in Kielce (€54 million) and the Human Brain Project at the Warsaw University of Technology (€54 million).[7]

Poland and the European Neighbourhood Policy[]

Poland has made a significant contribution to the European Neighbourhood Policy. The European Union is interested in Eastern Europe and, arguably, assisted with the development of democracy in the region by engaging in diplomatic discussions during the fall of communism and the Soviet Union in the late 1980s. The EU has started to focus on countries such as Ukraine, Belarus, Moldova, Azerbaijan, Armenia and Georgia.[8]

Before Poland's integration into the European Union, Polish politicians tried to strengthen economic and political cooperation with its neighbouring countries. These efforts were made in order to help the EU in its efforts of enlargement further into the European continent.[9]

Poland and the EU's common foreign and security policy[]

Poland has remained skeptical of the EU's common foreign and security policy and is opposed to giving further powers to the European Union's foreign and security policy.[8] EU countries such as France and Germany, want more favourable relations with Russia, however, Poland has strained relations and history with Russia and does not want to change their foreign policy. In addition, Poland is afraid that greater EU reach in foreign and security policy would violate Polish national interests and sovereignty.[8]

Poland has preferred to discuss and maintain relations with NATO and the United States, being skeptical about the possibility of a single EU security and defence policy being implemented. Poland participates in EU Crisis Management Operations. Polish troops participated in EU missions in Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, amongst others.[10]

Poland and the EU's enlargement[]

Poland supports the further development and enlargement of the European Union, and draws attention to the need to eliminate delaying the start of accession negotiations. Poland supports Montenegro, Serbia and Turkey's aspirations to join the EU. Poland welcomed the decision to grant Albania EU candidate status. Polish politicians stated that, acceptance of all the Balkan states and Turkey into the EU will prove that the EU's internal transformation has been completed, and that this would additionally help to bring greater stability to the entire region.[11] Poland participates in an informal group (called the "Tallinn Group") that supports the expansion of the EU.[11]

Poland's internal policies and the EU (2015-present)[]

On 13 January 2016 the European Commission, launched a formal rule-of-law assessment based on rules set out in 2014 and according to Article 7 of the Treaty of Lisbon regarding the amendments of the constitutional court and the public media law in Poland. The assessment could, theoretically, lead to Poland being stripped of its voting rights in the EU.[12] Some Polish and British media have criticised the EU's involvement in the Polish Constitutional Court crisis of 2015, as out-of-scope of the European Union's Framework to Strengthen the Rule of law.[13]

In September 2017 European Commission launched the second stage of infringement over the state of rule of law in Poland.[14][15][16] This came in the context of a quarrel between Poland and the EU that included also the logging of the Białowieża Forest, the refusal to accept refugees under the relocation program, and other issues.[17]

In 14 July 2021, The Polish Constitutional Tribunal rules that any interim measures from the top European court against Poland's judicial reforms were "not in line" with the Polish constitution. The Polish justice minister, Zbigniew Ziobro, said the constitutional court’s decision was "against interference, usurpation and legal aggression by organs of the European Union".[18][19][20]

In August 2021, in the context of the Poland-EU dispute over the Polish judicial reform, Ziobro said Poland should stay in the EU, but not ‘at any cost’.[21][22][23]

In September 2021, Ryszard Terlecki said that the PIS party wants to remain in the EU and have a cooperative relationship, but said that "drastic solutions" (seemingly referring to Polish withdrawal from the EU) may be necessary if the EU was not "acceptable to us".[24][25]

On 7 October 2021, Polish Constitutional Court ruled that parts of the Treaty on European Union were incompatible with its constitution, therefore opening a new conflict with the European Union.[26]

On 27 October 2021, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) fined Poland €1 million per day, for breaking the law by maintaining the disciplinary chamber of its Supreme Court, as a previous EU ruling called for the disciplinary chamber's suspension. The ECJ ruled that the chamber "[did] not guarantee judicial impartiality". The fine is the highest daily penalty the ECJ has ever imposed on any EU member state.[27]

Euroscepticism in Poland[]

In 22 November 2020, Do Rzeczy, a Polish conservative weekly newspaper, published a front-page article called "Polexit: We have the right to talk about it".[28]

The Polish far-right Confederation Liberty and Independence party has called for a withdrawal from the European Union on several occasions.[29][30]

Polling[]

In a January 2020 poll, found that 89 percent of Poles said Poland should stay in the EU while six percent said it should leave the union. While a November 20-23 poll found that 87% of Poles said Poland should remain as a member of the European Union and 8% (an increase) of those polled expressed the opposite view, while a further 5 percent was unable to decide.[31]

In July 2021, SW Research made a poll for the Rzeczpospolita daily, found that 16.9% of respondents answered positively when asked: "In your opinion, should Poland leave the EU?" while another 62.6% responded negatively and just over 20% did not have an opinion.[32]

See also[]

- Polexit

- Poland and the euro

- History of the European Union

- Stages of Poland's Integration into the EU (in Polish)

- LGBT ideology-free zone

References[]

- ^ "Population on 1 January". Eurostat. European Commission. Archived from the original on 9 January 2019. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ^ "Field Listing – Area". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 20 October 2018. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on January 21, 2015. Retrieved 2015-01-21.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "European Commission - PRESS RELEASES - Press release - Frequently asked questions on languages in Europe". europa.eu. Archived from the original on 2020-12-16. Retrieved 2017-06-24.

- ^ "EUROPA - Poland in the EU". europa.eu. 5 July 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-07-13. Retrieved 2016-07-12.

- ^ "Poland - EU Budget in my country - European Commission". ec.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 2016-07-02. Retrieved 2016-07-12.

- ^ "Poland - EU Budget in my country - European Commission". ec.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 2016-07-02. Retrieved 2016-07-12.

- ^ a b c Vitkus, G. (2008). European Union Foreign Policy. Quick Guide. Vilnius: Institute of International Relations and Political Science. p. 138. ISBN 978-9955-33-360-9.

- ^ "Partnerstwo Wschodnie". eastern-partnership.pl. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2016-07-12.

- ^ "Operacje i Misje UE". www.msz.gov.pl. Archived from the original on 2016-08-09. Retrieved 2016-07-12.

- ^ a b "Rozszerzenie Unii Europejskiej". www.polskawue.gov.pl. Archived from the original on 2015-10-08. Retrieved 2016-07-12.

- ^ Rankin, Jennifer (2016-01-13). "Brussels launches unprecedented EU inquiry into rule of law in Poland". the Guardian. Archived from the original on 2016-07-18. Retrieved 2016-07-12.

- ^ Gray, Boyden (2016-07-05). "The European Union Shows Poland Why We Have Brexit". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 2016-07-10. Retrieved 2016-07-12.

- ^ "Independence of the judiciary: European Commission takes second step in infringement procedure against Poland". 12 September 2017. Archived from the original on 21 September 2018. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- ^ "EU escalates pressure on Poland over rule of law". Archived from the original on 4 July 2018. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- ^ "Helsińska Fundacja Praw Człowieka » Rule of law procedure for Poland – European Commission takes another step". www.hfhr.pl. Archived from the original on 19 September 2018. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- ^ Pawłowska, Danuta (23 July 2018). "Poland's quarrel with the European Union". BiQdata/EDJNet. Archived from the original on 24 August 2018. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- ^ "Poland's judicial reform 'not compatible' with EU law, Court of Justice rules". France 24. July 15, 2021. Archived from the original on July 15, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- ^ "Poland's top court rejects EU court injunctions as invalid". www.aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 2021-07-15. Retrieved 2021-07-15.

- ^ "'Legal Polexit': Poland court rules EU measures unconstitutional". the Guardian. July 14, 2021. Archived from the original on August 12, 2021. Retrieved August 12, 2021.

- ^ "Polish minister: Poland should not stay in the EU 'at any cost'". POLITICO. August 6, 2021. Archived from the original on August 9, 2021. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- ^ "Poland should not stay in EU at all costs, says minister". Reuters. August 6, 2021. Archived from the original on 2021-08-08. Retrieved 2021-08-09.

- ^ Warsaw, James Shotter in. "Poland should not stay in EU at 'any price', minister says". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 2021-08-08. Retrieved 2021-08-09.

- ^ Macej, Piotr (10 September 2021). "Poland's ruling PiS sends mixed signals on 'Polexit'". Euractiv.com. Archived from the original on 2021-10-16. Retrieved 2021-11-26.

- ^ Skolimowski, Piotr. "Polish Ruling Party Official Backpedals EU Exit Suggestion". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 2021-10-16. Retrieved 2021-11-26.

- ^ "Polish court rules that EU laws incompatible with its constitution". the Guardian. 2021-10-07. Archived from the original on 2021-10-07. Retrieved 2021-10-07.

- ^ Welle (www.dw.com), Deutsche. "EU fines Poland €1 million per day over judicial reforms | DW | 27.10.2021". DW.COM (in British English). Archived from the original on 2021-10-28. Retrieved 2021-10-28.

- ^ "[Analysis] Playing with fire - Poland's PiS reach for the 'Polexit' matches". EUobserver. Archived from the original on 2021-07-15. Retrieved 2021-07-15.

- ^ "Anti-EU Block forms on the Polish right". PolandIn. Telewizja Polska. 1 March 2019. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ ""Łączy nas Polexit". Narodowcy i Korwin-Mikke łączą siły przed wyborami do PE". Do Rzeczy (in Polish). 2018-12-06. Archived from the original on 2020-09-29. Retrieved 2020-09-30.

- ^ "Overwhelming majority of Poles for staying in EU - poll". www.thefirstnews.com. Archived from the original on 2021-07-15. Retrieved 2021-07-15.

- ^ "Sondaż: Prawie 17 proc. Polaków za polexitem". Rzeczpospolita (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2021-10-15. Retrieved 2021-10-12.

External links[]

- History of the European Union

- Poland and the European Union

- Enlargement of the European Union