Poles

Polacy (Polish) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Total population | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| c. 60 million[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Regions with significant populations | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10,600,000 (2015)[1][5][4] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1,800,000 (2007)[6] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2,253,000 (2018)[7] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1,350,000 (2012)[8][9] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1,010,705 (2013)[10] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 695,000 (2019)[11] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 500,000 (2014)[12] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Languages | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predominantly Roman Catholicism[33] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Related ethnic groups | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Czechs, Gorals, Kashubians, Moravians, Silesians, Slovaks, Sorbs | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Poles,[a] or Polish people, are a nation and an ethnic group of predominantly West Slavic descent, who share a common history, culture, the Polish language and are identified with the country of Poland in Central Europe. The preamble to the Constitution of the Republic of Poland defines the Polish nation as comprising all the citizens of Poland, regardless of heritage or ethnicity.

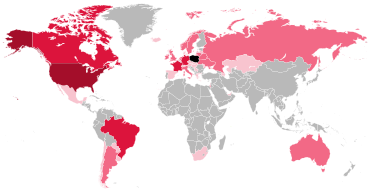

The population of self-declared Poles in Poland is estimated at 37,394,000 out of an overall population of 38,512,000 (based on the 2011 census),[2] of whom 36,522,000 declared Polish alone.[3][34][4] A wide-ranging Polish diaspora (the Polonia) exists throughout Europe, the Americas, and in Australasia. Today, the largest urban concentrations of Poles are within the Warsaw and Silesian metropolitan areas.

Ethnic Poles are considered to be the descendants of the ancient Lechites and other tribes that inhabited the Polish territories during the late antiquity period. Poland's recorded history dates back over a thousand years to c. 930–960 AD, when the Western Polans – an influential tribe in the Greater Poland region – united various Lechitic clans under what became the Piast dynasty,[35] thus creating the first Polish state. The subsequent Christianization of Poland by the Catholic Church, in 966 CE, marked Poland's advent to the community of Western Christendom. However, throughout its existence, the Polish state followed a tolerant policy towards minorities resulting in numerous ethnic and religious identities of the Poles, such as Polish Jews.

Poles have made important contributions to the world in every major field of human endeavor, among them Copernicus, Marie Curie, Joseph Conrad, Frédéric Chopin and Pope John Paul II. Notable Polish émigrés – many of them forced from their homeland by historic vicissitudes – have included physicist Joseph Rotblat, mathematician Stanisław Ulam, pianist Arthur Rubinstein, actresses Helena Modjeska and Pola Negri, military leaders Tadeusz Kościuszko and Casimir Pulaski, U.S. National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski, politician Rosa Luxemburg, painter Tamara de Lempicka, filmmakers Samuel Goldwyn and the Warner Brothers, cartoonist Max Fleischer, and cosmeticians Helena Rubinstein and Max Factor.

Names and exonyms

The Polish endonym Polacy is derived from the Western Polans, a Lechitic tribe which inhabited lands around the River Warta in Greater Poland region from the mid-6th century onward.[36] The tribe's name stems from the Proto-Indo European *pleh₂-, which means flat or flatland and corresponds to the topography of a region that the Western Polans initially settled.[37][38] The prefix pol- is used in most world languages when referring to Poles (Spanish polaco, Italian polacche, French polonais, German Pole).

Among other foreign exonyms for the Polish people are Lithuanian Lenkai; Hungarian Lengyelek; Turkish Leh; Armenian: Լեհաստան Lehastan; and Persian: لهستان (Lahestān). These stem from Lechia, the ancient name for Poland, or from the tribal Lendians. Their names are equally derived from the Old Polish term lęda, meaning plain or field.[39]

Origins

The territory of present-day Poland has been settled by various peoples and ethnic groups for centuries before the Polish state emerged in 966 AD. In late antiquity, these groups comprised Celtic, Scythian, Germanic, Sarmatian, Slavic and Baltic tribes.[40] During the Migration Period, the eastern parts of Magna Germania (today Poland) were becoming increasingly settled by the early Slavs (500–700 AD).[41] They organized into tribal units, of which the larger ones further west were later known as the Polish tribes (Lechites); the names of many tribes are found on the list compiled by the anonymous Bavarian Geographer in the 9th century.[42] However, there is strong evidence that Poles are the descendants of other ethnic groups which inhabited the Central European Plain long before the migration began and assimilated with time.[43] In the 9th and 10th centuries the tribes gave rise to developed regions along the upper Vistula (the Vistulans within the Great Moravian Empire sphere),[42] the Baltic Sea coast and in Greater Poland. The last tribal undertaking in the 10th century resulted in a lasting political structure and state.[44]

Throughout the centuries, Poland and its monarchs pursued a tolerant policy towards religious and ethnic minorities, which enhanced migration from other regions of Europe.[45] As the country expanded, so did its demographic composition – following the 1569 Union of Lublin, Poland joined neighbouring Lithuania in forming the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, one of the largest countries on the continent at the time.[46] Thus, Lithuania's more multicultural society fell under Polish influence and societal integration between the two strengthened. No official statistics or records can precisely manifest the extent of the diversity – it is believed that among the largest groups were Poles, Lithuanians, Germans, Ruthenians (chiefly Ukrainians) and Jews. The Commonwealth also hosted refugees fleeing from persecution, or foreign traders and merchants including Czechs, Hungarians, Livonians, Romanis, Vlachs, Armenians, Italians, Scots and the Dutch.[47]

Language

Polish is the native language of most Poles. It is a West Slavic language of the Lechitic group and the sole official language in the Republic of Poland. Its written form uses the Polish alphabet, which is the basic Latin alphabet with the addition of six diacritic marks, totalling 32 letters. Bearing relation to Czech and Slovakian, it has been profoundly influenced by Latin, German and other languages over the course of history.[48][49] Poland is linguistically homogeneous – nearly 97% of Poland's citizens declare Polish as their mother tongue.[50]

Polish-speakers use the language in a uniform manner throughout most of Poland, though numerous dialects and a vernacular language in certain regions coexist alongside standard Polish. The most common dialects in Poland are Silesian, spoken in Upper Silesia, and Kashubian, widely spoken in historic Eastern Pomerania (Pomerelia), today in the northwestern part of Poland.[51] Kashubian possesses its own status as a separate language.[52][53] The Goral people in the mountainous south use their own nonstandard dialect, accenting and different intonation.

The geographical distribution of the Polish language was greatly affected by the border changes and population transfers that followed the Second World War – forced expulsions and resettlement during that period contributed to the country's current linguistic homogeneity.

Culture

The culture of Poland has a history of over 1000 years.[54] Poland developed a character that was influenced by its geography at the confluence of fellow Central European countries, most notably German, Austrian, Czech and Slovak as well as other European cultures.[55] Owing to this central location, the Poles came very early into contact with many civilizations, and, as a result, developed economically, culturally, and politically. Strong ties with the Latinate world and the Roman Catholic faith also shaped Poland's cultural identity.

Officially, the national and state symbol is the white-tailed eagle (bielik) embedded on the Coat of arms of Poland (godło).[56] The national colours are white and red, which appropriately appear on the flag of Poland (flaga), banners, cockades and memorabilia.[56]

Personal achievement and education plays an important role in Polish society today. In 2018, the Programme for International Student Assessment ranked Poland 11th in the world for mathematics, science and reading.[57] Education has been of prime interest to Poland since the early 12th century, particularly for its noble classes. In 1364, King Casimir the Great founded the Kraków Academy, which would become Jagiellonian University, the second-oldest institution of higher learning in Central Europe.[58] People of Polish birth have made considerable contributions in the fields of science, technology and mathematics both in Poland and abroad,[59] among them Vitello, Nicolaus Copernicus, Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit (Polish-born), Marie Curie, Rudolf Weigl, Bronisław Malinowski, Stefan Banach, Stanisław Ulam, Leonid Hurwicz, Benoit Mandelbrot (Polish-born) and Alfred Tarski. Copernicus and Marie Skłodowska-Curie left a particularly enduring scientific legacy.

Poland's polka-styled dances and folk music, especially the mazurka, krakowiak and polonaise, were popularized by Polish composer Frédéric Chopin, and they soon spread across Europe and elsewhere.[60] Latin songs and religious hymns such as Gaude Mater Polonia and Bogurodzica were once chanted in churches and during patriotic festivities, but the tradition has faded.

According to a 2020 study, Poland ranks 12th globally on a list of countries which read the most, and approximately 79% of Poles read the news more than once a day, placing it 2nd behind Sweden.[61] As of 2021, six Poles received the Nobel Prize in Literature.[b] The national epic is Pan Tadeusz (English: Master Thaddeus), written by Adam Mickiewicz. Renowned novelists who gained much recognition abroad include Joseph Conrad (wrote in English; Heart of Darkness, Lord Jim), Stanisław Lem (science-fiction; Solaris) and Andrzej Sapkowski (fantasy; The Witcher).

Poland was for centuries a refuge to many Jews, who became an important part of Polish society. Similarly, some provinces and historical regions in Poland such as Mazovia, Silesia, Kuyavia, Lesser Poland, Greater Poland and Pomerania developed their own distinct cultures, habits, cuisines, costumes and dialects.

Popular everyday foods in Poland include schnitzels or pork cutlets (kotlet schabowy), kielbasa sausage, potatoes, coleslaw and salads, soups (tomato or meat broth), pierogi dumplings, Kaiser bread rolls and frikadellers. Traditional Polish cuisine is hearty and Poles are one of the more obese nations in Europe – approximately 58% of the adult population was overweight in 2019, above the EU average.[62] According to data from 2017, meat consumption per capita in Poland was one of the highest in the world, with pork being the most in demand.[63] Alcohol consumption is relatively moderate compared to other European states;[64] popular alcoholic beverages include Polish-produced beer, vodka and ciders.

Religion

Poles have traditionally adhered to the Christian faith; an overwhelming majority belongs to the Roman Catholic Church,[65] with 87.5% of Poles in 2011 identifying as Roman Catholic.[66] According to Poland's Constitution, freedom of religion is ensured to everyone. It also allows for national and ethnic minorities to have the right to establish educational and cultural institutions, institutions designed to protect religious identity, as well as to participate in the resolution of matters connected with their cultural identity.

There are smaller communities primarily comprising Protestants (especially Lutherans), Orthodox Christians (migrants), Jehovah's Witnesses, those irreligious, and Judaism (mostly from the Jewish populations in Poland who have lived in Poland prior to World War II)[67] and Sunni Muslims (Polish Tatars). Roman Catholics live all over the country, while Orthodox Christians can be found mostly in the far north-eastern corner, in the area of Białystok, and Protestants in Cieszyn Silesia and Warmia-Masuria regions. A growing Jewish population exists in major cities, especially in Warsaw, Kraków and Wrocław. Over two million Jews of Polish origin reside in the United States, Brazil, and Israel.[citation needed]

Religious organizations in the Republic of Poland can register their institution with the Ministry of Interior and Administration creating a record of churches and other religious organizations who operate under separate Polish laws. This registration is not necessary; however, it is beneficial when it comes to serving the freedom of religious practice laws.[citation needed]

Slavic Native Faith (Rodzimowiercy) groups, registered with the Polish authorities in 1995, are the Native Polish Church (Rodzimy Kościół Polski), which represents a pagan tradition going back to Władysław Kołodziej's 1921 Holy Circle of Worshippers of Światowid (Święte Koło Czcicieli Światowida), and the Polish Slavic Church (Polski Kościół Słowiański). There is also the Native Faith Association (Zrzeszenie Rodzimej Wiary, ZRW), founded in 1996.[68]

Geographic distribution

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2021) |

Polish people are the sixth-largest national group in the European Union (EU).[69] Estimates vary depending on source, though available data suggest a total number of around 60 million people worldwide (with roughly 18-20 million living outside of Poland, many of whom are not of Polish ethnicity, but Polish nationals).[70] There are almost 38 million Poles in Poland alone. There are also strong Polish communities in neighbouring countries, whose territories were once occupied or part of Poland – Czech Republic, Slovakia, Lithuania, Latvia, western Ukraine, and western Belarus.

The term "Polonia" is usually used in Poland to refer to people of Polish origin who live outside Polish borders. There is a notable Polish diaspora in the United States, Brazil, and Canada. France has a historic relationship with Poland and has a relatively large Polish-descendant population. Poles have lived in France since the 18th century. In the early 20th century, over a million Polish people settled in France, mostly during world wars, among them Polish émigrés fleeing either Nazi occupation (1939–1945) or Communism (1945/1947–1989).

In the United States, a significant number of Polish immigrants settled in Chicago (billed as the world's most Polish city outside of Poland), Milwaukee, Ohio, Detroit, New Jersey, New York City, Orlando, Pittsburgh, Buffalo, and New England. The highest concentration of Polish Americans in a single New England municipality is in New Britain, Connecticut. The majority of Polish Canadians have arrived in Canada since World War II. The number of Polish immigrants increased between 1945 and 1970, and again after the end of Communism in Poland in 1989. In Brazil, the majority of Polish immigrants settled in Paraná State. Smaller, but significant numbers settled in the states of Rio Grande do Sul, Espírito Santo and São Paulo (state). The city of Curitiba has the second largest Polish diaspora in the world (after Chicago) and Polish music, dishes and culture are quite common in the region.

A recent large migration of Poles took place following Poland's accession to the European Union in 2004 and with the opening of the EU's labor market; an approximate number of 2 million, primarily young, Poles taking up jobs abroad.[71] It is estimated that over half a million Polish people have come to work in the United Kingdom from Poland. Since 2011, Poles have been able to work freely throughout the EU and not just in the United Kingdom, but also countries like Ireland and Sweden where they have had full working rights since Poland's EU accession in 2004. The Polish community in Norway has increased substantially and has grown to a total number of 120,000, making Poles the largest immigrant group in Norway. Only in recent years has the population abroad decreased, specifically in the UK with 116.000 leaving the UK in 2018 alone.

See also

- Demographics of Poland

- Karta Polaka

- Lechites

- List of Poles

- Name of Poland (etymology of the demonym)

- Pole, Hungarian, two good friends

- Poles in Germany

- Poles in Lithuania

- Poles in Romania

- Poles in the former Soviet Union

- Poles in the United Kingdom

- Polish Americans

- Polish Argentines

- Polish Australians

- Polish Brazilians

- Polish British

- Polish Canadians

- Polish Chileans

- Polish Mexicans

- Polish minority in France

- Polish minority in Spain

- Poles in Latvia

- Polish Czechs

- Polish nationality law

- Polish New Zealanders

- Polish Norwegians

- Polish Uruguayan

- Polish Venezuelans

- Polonization

- Sons of Poland

- West Slavs

Notes

References

- ^ a b 37.5–38 million in Poland and 21–22 million ethnic Poles or people of ethnic Polish extraction elsewhere. "Polmap. Rozmieszczenie ludności pochodzenia polskiego (w mln)" Archived 30 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Central Statistical Office (January 2013). "The national-ethnic affiliation in the population – The results of the census of population and housing in 2011" (PDF) (in Polish). p. 1. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ a b Gudaszewski, Grzegorz (November 2015). Struktura narodowo-etniczna, językowa i wyznaniowa ludności Polski. Narodowy Spis Powszechny Ludności i Mieszkań 2011 (PDF). Warsaw: Główny Urząd Statystyczny. pp. 132–136. ISBN 978-83-7027-597-6.

- ^ a b c Główny Urząd Statystyczny (January 2013). Ludność. Stan i struktura demograficzno-społeczna [Narodowy Spis Powszechny Ludności i Mieszkań 2011] (PDF) (in Polish). Główny Urząd Statystyczny. pp. 89–101. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ^ "Stowarzyszenie Wspólnota Polska". Wspolnota-polska.org.pl. Archived from the original on 24 October 2013. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Polska Diaspora na świecie, Stowarzyszenie Wspólnota Polska, 2007. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- ^ Bevölkerung mit Migrationshintergrund - Ergebnisse des Mikrozensus - Fachserie 1 Reihe 2.2 - 2018, page 62, retrieved 29 November 2019.

- ^ "Présentation de la Pologne".

- ^ "Europe: where do people live?". Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- ^ "Ethnic Origin (264), Single and Multiple Ethnic Origin Responses (3), Generation Status (4), Age Groups (10) and Sex (3) for the Population in Private Households of Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2011 National Household Survey". 8 May 2013.

- ^ "Polish workers abandon brexit Britain in favour of Germany:Aljazeera.com". Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ "Clarín.com – La ampliación de la Unión Europea habilita a 600 mil argentinos para ser comunitarios". Edant.clarin.com. 27 April 2004. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ^ "Changes in the populations of the majority ethnic groups". Belstat.gov.by. Archived from the original on 28 July 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ^ a b c Wspólnota Polska. "Stowarzyszenie Wspólnota Polska". Wspolnota-polska.org.pl. Archived from the original on 24 October 2013. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 15 July 2020. Retrieved 7 November 2021.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Jews, by Country of Origin and Age". Statistical Abstract of Israel (in English and Hebrew). Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. 26 September 2011. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ^ "A. Butkus. Lietuvos gyventojai tautybės požiūriu | Alkas.lt". 16 December 2015.

- ^ "Ukrainian Census 2001". 2001.ukrcensus.gov.ua. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ^ "Polacy przestali kochać Irlandię. Myślą o powrocie". 17 October 2018.

- ^ "Immigrants and Norwegian-born to immigrant parents". 9 March 2020.

- ^ "Maleje liczba Polaków we Włoszech" [The number of Poles in Italy is decreasing]. Naszswiat.net (in Polish). Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ "Befolkning efter födelseland och ursprungsland 31 december 2012" (in Swedish). Statistics Sweden. 31 December 2013. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ a b c "Immigrant and Emigrant Populations by Country of Origin and Destination". 10 February 2014.

- ^ "On key provisional results of Population and Housing Census 2011". Csb.gov.lv. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ^ "Statistics Denmark:FOLK1: Population at the first day of the quarter by sex, age, ancestry, country of origin and citizenship". Statistics Denmark. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- ^ "Kazakhstan National Census 2009". Stat.kz. Archived from the original on 18 November 2018.

- ^ Wspólnota Polska. "Stowarzyszenie Wspólnota Polska". Wspolnota-polska.org.pl. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ^ https://www.czso.cz/documents/11292/27914491/1612_c01t14.pdf/4bbedd77-c239-48cd-bf5a-7a43f6dbf71b?version=1.0

- ^ Vukovich, Gabriella (2018). Mikrocenzus 2016 - 12. Nemzetiségi adatok [2016 microcensus - 12. Ethnic data] (PDF). Hungarian Central Statistical Office (in Hungarian). Budapest. ISBN 978-963-235-542-9. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- ^ "Population by country of birth, sex and age 1 January 1998-2018". Statistics Iceland. 2018. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- ^ "Ante la crisis, Europa y el mundo miran a Latinoamérica" (in Spanish). Acercando Naciones. 2012. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015.

- ^ "Niektóre wyznania religijne w Polsce w 2017 r. (Selected religious denominations in Poland in 2017)" (PDF). Mały Rocznik Statystyczny Polski 2018 (Concise Statistical Yearbook of Poland 2018). Concise Statistical Yearbook of Poland = Mały Rocznik Statystyczny Polski (in Polish and English). Warszawa: Główny Urząd Statystyczny. 2018. pp. 114–115. ISSN 1640-3630.

- ^ Struktura narodowo-etniczna, językowa i wyznaniowa ludności Polski [Narodowy Spis Powszechny Ludności i Mieszkań 2011] (PDF) (in Polish). Warsaw: Główny Urząd Statystyczny. November 2015. pp. 129–136. ISBN 978-83-7027-597-6.

- ^ Gerard Labuda. Fragmenty dziejów Słowiańszczyzny zachodniej, t.1–2 p.72 2002; Henryk Łowmiański. Początki Polski: z dziejów Słowian w I tysiącleciu n.e., t. 5 p.472; Stanisław Henryk Badeni, 1923. p. 270.

- ^ Gliński, Mikołaj (6 December 2016). "The Many Different Names of Poland". Culture.pl. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

- ^ Lehr-Spławiński, Tadeusz (1978). Język polski. Pochodzenie, powstanie, rozwój. Warszawa (Warsaw): Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe. p. 64.

- ^ Potkański, Karol (2004) [1922]. Pisma pośmiertne. Granice plemienia Polan. Volume 1 & 2. Kraków: Polska Akademia Umiejętności. p. 423. ISBN 9788370634117.

|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Małecki, Antoni (1907). Lechici w świetle historycznej krytyki. Lwów: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich. p. 37. ISBN 9788365746641.

- ^ Davies, Norman (2001). Heart of Europe. The Past in Poland's Present. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 247. ISBN 9780192801265.

- ^ Zbigniew Kobyliński. "The Slavs" in Paul Fouracre. The New Cambridge Medieval History, pp. 530–537

- ^ a b Davies, Norman (2005). God's Playground A History of Poland: Volume 1: The Origins to 1795: Origins. OUP Oxford. p. xxvii. ISBN 978-0199253395.

- ^ Mielnik-Sikorska, Marta; et al. (2013), "The History of Slavs Inferred from Complete Mitochondrial Genome Sequences", PLOS ONE, 8 (1): e54360, Bibcode:2013PLoSO...854360M, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0054360, PMC 3544712, PMID 23342138

- ^ Derwich, Marek; Żurek, Adam (2002). U źródeł Polski (do roku 1038) (in Polish). pp. 122–143.

- ^ # Norman Davies, God's Playground. A History of Poland, Vol. 1: The Origins to 1795, Vol. 2: 1795 to the Present. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-925339-0 / ISBN 0-19-925340-4

- ^ Butterwick, Richard (2021). The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, 1733-1795. Yale University Press. p. 21. ISBN 9780300252200.

- ^ Kopczyński, Michał; Tygielski, Wojciech (2010). Pod wspólnym niebem. Narody dawnej Rzeczypospolitej (in Polish). Warszawa: Bellona. ISBN 9788311117242.

- ^ "Język polski". Towarzystwo Miłośników Języka Polskiego. 27 July 2000 – via Google Books.

- ^ Mańczak-Wohlfeld, Elżbieta (27 July 1995). Tendencje rozwojowe współczesnych zapożyczeń angielskich w języku polskim. Universitas. ISBN 978-83-7052-347-3 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Which Languages Are Spoken in Poland?". WorldAtlas.

- ^ Lucjan Adamczuk, Sławomir Łodziński (2006). Mniejszości narodowe w Polsce w świetle Narodowego Spisu Powszechnego z 2002 roku. Warszawa (Warsaw): Wydawn. Nauk. Scholar. p. 149. ISBN 9788373831438.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- ^ "Acta Cassubiana. Vol. XVII (map on p. 122)". Instytut Kaszubski. 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ "Kaschuben heute: Kultur-Sprache-Identität" (PDF) (in German). 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 January 2016. Retrieved 3 January 2016.

- ^ Adam Zamoyski, The Polish Way: A Thousand Year History of the Poles and Their Culture. Published 1993, Hippocrene Books, Poland, ISBN 0-7818-0200-8

- ^ Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Poland, 2002–2007, AN OVERVIEW OF POLISH CULTURE. Access date 13 December 2007.

- ^ a b (in Polish) Konstytucja Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej [(in English) Constitution of the Republic of Poland], Dz.U. 1997 nr 78 poz. 483 Archived October 7, 2009, at WebCite

- ^ "PISA 2018 results". oecd.org. OECD. 2018. Retrieved 29 September 2021.

- ^ Zachara, Małgorzata (2018). Poland in Transatlantic Relations after 1989. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 323. ISBN 9781527507401.

- ^ Nodzyńska, Małgorzata; Cieśla, Paweł (2012). From alchemy to the present day – the choice of biographies of Polish scientists. Cracow: Pedagogical University of Kraków. ISBN 978-83-7271-768-9.

- ^ Berend, Ivan T. (2005). History Derailed. Central and Eastern Europe in the Long Nineteenth Century. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 66. ISBN 9780520245259.

- ^ Cabrera, Isabel (2020). "World Reading Habits in 2020 [Infographic]". geediting.com. Global English Editing. Retrieved 29 September 2021.

- ^ Eurostat (2019). "Overweight and obesity - BMI statistics". ec.europa.eu. European Union. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- ^ Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) (2017). "Food balances data 2017". FAO.org. Retrieved 21 October 2021.

- ^ "WHO Global status report on alcohol and health 2018" (PDF). who.int. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 February 2021.

- ^ "Europe :: Poland — the World Factbook - Central Intelligence Agency". The World Factbook. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ^ GUS, Narodowy Spis Powszechny Ludnosci 2011: 4.4. Przynależność wyznaniowa (National Survey 2011: 4.4 Membership in faith communities) p. 99/337 (PDF file, direct download 3.3 MB). ISBN 978-83-7027-521-1 Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- ^ (in Polish) Kościoły i związki wyznaniowe w Polsce Archived 5 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 17 June 2008.

- ^ Scott Simpson, Native Faith: Polish Neo-Paganism at the Brink of the 21st Century, 2000.

- ^ NationMaster.com 2003–2008. People Statistics: Population (most recent) by country. Retrieved 25 January 2008.

- ^ "Record number of Poles in Britain: statistics office" (in Polish). association "Polish Community". Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ^ ""Sueddeutsche Zeitung": Polska przeżywa największą falę emigracji od 100 lat". Wiadomosci.onet.pl. 26 September 2014. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to People of Poland. |

- Polish people

- Ethnic groups in Poland

- Slavic ethnic groups

- Lechites