Sarmatians

The Sarmatians (/sɑːrˈmeɪʃiənz/; Greek: Σαρμάται, Σαυρομάται; Latin: Sarmatae [ˈsar.mat̪ae̯], Sauromatae [sau̯ˈrɔmat̪ae̯]) were a large Iranian confederation that existed in classical antiquity, flourishing from about the fifth century BC to the fourth century AD.

Originating in the central parts of the Eurasian Steppe, the Sarmatians were part of the wider Scythian cultures.[1] They started migrating westward around the fourth and third centuries BC, coming to dominate the closely related Scythians by 200 BC. At their greatest reported extent, around 100 BC, these tribes ranged from the Vistula River to the mouth of the Danube and eastward to the Volga, bordering the shores of the Black and Caspian seas as well as the Caucasus to the south.

Their territory, which was known as Sarmatia (/sɑːrˈmeɪʃiə/) to Greco-Roman ethnographers, corresponded to the western part of greater Scythia (it included today's Central Ukraine, South-Eastern Ukraine, Southern Russia, Russian Volga, and South-Ural regions, also to a smaller extent northeastern Balkans and around Moldova). In the first century AD, the Sarmatians began encroaching upon the Roman Empire in alliance with Germanic tribes. In the third century AD, their dominance of the Pontic Steppe was broken by the Germanic Goths. With the Hunnic invasions of the fourth century, many Sarmatians joined the Goths and other Germanic tribes (Vandals) in the settlement of the Western Roman Empire. Since large parts of today's Russia, specifically the land between the Ural Mountains and the Don River, were controlled in the fifth century BC by the Sarmatians, the Volga–Don and Ural steppes sometimes are called "Sarmatian Motherland".[2][3]

The Sarmatians were eventually decisively assimilated (e.g. Slavicisation) and absorbed by the Proto-Slavic population of Eastern Europe.[4]

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

| History of Ukraine |

|---|

|

|

|

| History of Russia | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

|

Prehistory • Antiquity • Early Slavs

Feudal Rus' (1097–1547) Mongol conquest • Vladimir-Suzdal Grand Duchy of Moscow • Novgorod Republic

Russian Revolution (1917–1923) February Revolution • Provisional Government

|

||||||||||||||

|

Timeline 860–1721 • 1721–1796 • 1796–18551855–1892 • 1892–1917 • 1917–1927 1927–1953 • 1953–1964 • 1964–1982 1982–1991 • 1991–present |

||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

Etymology[]

Sarmatae probably originated as just one of several tribal names of the Sarmatians, but one that Greco-Roman ethnography came to apply as an exonym to the entire group. Strabo in the first century names as the main tribes of the Sarmatians the Iazyges, the Roxolani, the Aorsi, and the Siraces.

The Greek name Sarmatai sometimes appears as "Sauromatai" (Σαυρομάται), which is almost certainly no more than a variant of the same name. Nevertheless, historians often regarded these as two separate peoples, while archaeologists habitually use the term 'Sauromatian' to identify the earliest phase of Sarmatian culture. Any idea that the name derives from the word lizard (sauros), linking to the Sarmatians' use of reptile-like scale armour and dragon standards, is almost certainly unfounded.[5] Whereas the word "ὀμμάτιον/ μάτι", meaning eye, would suggest the origin of the name could be due to having what appeared as lizard eyes to Greeks.

Both Pliny the Elder (Natural History book iv) and Jordanes recognised the Sar- and Sauro- elements as interchangeable variants, referring to the same people. Greek authors of the fourth century (Pseudo-Scylax, Eudoxus of Cnidus) mention Syrmatae as the name of a people living at the Don, perhaps reflecting the ethnonym as it was pronounced in the final phase of Sarmatian culture.

English scholar Harold Walter Bailey (1899–1996) derived the base word from Avestan sar- (to move suddenly) from tsar- in Old Iranian (tsarati, tsaru-, hunter), which also gave its name to the western Avestan region of Sairima (*salm, – *Sairmi), and also connected it to the tenth–eleventh century AD Persian epic Shahnameh's character "Salm".[6]

Oleg Trubachyov derived the name from the Indo-Aryan *sar-ma(n)t (feminine – rich in women, ruled by women), the Indo-Aryan and Indo-Iranian word *sar- (woman) and the Indo-Iranian adjective suffix -ma(n)t/wa(n)t.[7] By this derivation was noted the high status of women (matriarchy) that was unusual from the Greek point of view and went to the invention of Amazons (thus the Greek name for Sarmatians as Sarmatai Gynaikokratoumenoi, ruled by women).[7]

The Sarmatians themselves apparently called themselves "Aryans", "Arii".[8]

Ethnology[]

The Sarmatians were part of the Iranian steppe peoples, among whom were also Scythians and Saka.[9] These also are grouped together as "East Iranians".[10] Archaeology has established the connection 'between the Iranian-speaking Scythians, Sarmatians, and Saka and the earlier Timber-grave and Andronovo cultures'.[11] Based on building construction, these three peoples were the likely descendants of those earlier archaeological cultures.[12] The Sarmatians and Saka used the same stone construction methods as the earlier Andronovo culture.[13] The Timber grave (Srubnaya culture) and Andronovo house building traditions were further developed by these three peoples.[14] Andronovo pottery was continued by the Saka and Sarmatians.[15] Archaeologists describe the Andronovo culture people as exhibiting pronounced Caucasoid features.[16]

The first Sarmatians are mostly identified with the Prokhorovka culture, which moved from the southern Urals to the Lower Volga and then to the northern Pontic steppe, in the fourth–third centuries BC. During the migration, the Sarmatian population seems to have grown and they divided themselves into several groups, such as the Alans, Aorsi, Roxolani, and Iazyges. By 200 BC, the Sarmatians replaced the Scythians as the dominant people of the steppes.[17] The Sarmatians and Scythians had fought on the Pontic steppe to the north of the Black Sea.[18] The Sarmatians, described as a large confederation,[19] were to dominate these territories over the next five centuries.[20] According to Brzezinski and Mielczarek, the Sarmatians were formed between the Don River and the Ural Mountains.[20] Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD) wrote that they ranged from the Vistula River (in present-day Poland) to the Danube.

The Sarmatians differed from the Scythians in their veneration of a fire deity rather than a nature deity, and the prominent role of women in warfare that may have served as inspiration for the Amazons.

Speculation about origin[]

There are two theories accounting for the origin of the Sarmatian culture.

- The first theory holds that the Sarmatian culture was fully formed by the end of the fourth century BC, based on the combination of local Sauromatian culture of Southern Ural and foreign elements brought by tribes advancing from the forest-steppe Zauralye (Itkul culture, Gorohovo culture), from Kazakhstan and possibly from the Aral Sea region.[21] Changes to the culture occurred sometime between the fourth and third century BC, when a mass migration carried nomads of the Southern Ural to the west in the Lower Volga and a smaller migration to the north, south, and east. At the same time, eastern nomads in the Lower Volga, either partly assimilated local Sauromatian tribes or pushed them into the Azov Sea and the Western Caucasus, where they subsequently formed a basis of nomadic association. A merging of the Southern Ural Prokhorovka culture with the Lower Volga or Sauromatian culture is thought to have created the local differences between Prokhorovka monuments of Southern Ural and those of the Volga–Don region within a single culture.

- The second theory holds that the Sarmatian culture in the Southern Ural evolved from the early Prokhorovka culture and that the culture of the Lower Volga Sauromates developed at the same time as an independent community.[22]

Archaeology[]

In 1947, Soviet archaeologist Boris Grakov[citation needed] defined a culture flourishing from the sixth century BC to the fourth century AD, apparent in late kurgan graves (buried within earthwork mounds), sometimes reusing part of much older kurgans.[23] It was a nomadic steppe culture ranging from the Black Sea eastward to beyond the Volga that is especially evident at two of the major sites at Kardaielova and Chernaya in the trans-Uralic steppe. The four phases – distinguished by grave construction, burial customs, grave goods, and geographical spread – are:[19][24]

- Sauromatian, sixth–fifth centuries BC

- Early Sarmatian, fourth–second centuries BC, also called the Prokhorovka culture

- Middle Sarmatian, late second century BC to late second century AD

- Late Sarmatian, late second century AD to fourth century AD

While "Sarmatian" and "Sauromatian" are synonymous as ethnonyms, purely by convention they are given different meanings as archaeological technical terms. The term "Prokhorovka culture" derives from a complex of mounds in the Prokhorovski District, Orenburg region, excavated by S. I. Rudenko in 1916.[25]

Reportedly, during 2001 and 2006 a great Late Sarmatian pottery centre was unearthed near Budapest, Hungary in the Üllő5 archaeological site. Typical grey, granular Üllő5 ceramics form a distinct group of Sarmatian pottery is found ubiquitously in the north-central part of the Great Hungarian Plain region, indicating a lively trading activity.

A 1998 paper on the study of glass beads found in Sarmatian graves suggests wide cultural and trade links.[26]

Archaeological evidence suggests that Scythian-Sarmatian cultures may have given rise to the Greek legends of Amazons. Graves of armed women have been found in southern Ukraine and Russia. David Anthony noted that approximately 20% of Scythian-Sarmatian "warrior graves" on the lower Don and lower Volga contained women dressed for battle as warriors and he asserts that encountering that cultural phenomenon "probably inspired the Greek tales about the Amazons".[27]

Language[]

The Sarmatians spoke an Iranian language that was derived from 'Old Iranian' and it was heterogenous. By the first century BC, the Iranian tribes in what is today South Russia spoke different languages or dialects, clearly distinguishable.[28] According to a group of Iranologists writing in 1968, the numerous Iranian personal names in Greek inscriptions from the Black Sea coast indicate that the Sarmatians spoke a North-Eastern Iranian dialect ancestral to Alanian-Ossetian.[29] However, Harmatta (1970) argued that "the language of the Sarmatians or that of the Alans as a whole cannot be simply regarded as being Old Ossetian".[28]

Genetics[]

A genetic study published in Nature Communications in March 2017 examined several Sarmatian individuals buried in Pokrovka, Russia (southwest of the Ural Mountains) between the fifth century BC and the second century BC. The sample of Y-DNA extracted belonged to haplogroup R1a1a2a2. This was the dominant lineage among males of the earlier Yamnaya culture.[30] The eleven samples of mtDNA extracted belonged to the haplogroups U3, M, U1a'c, T, F1b, N1a1a1a1a, T2, U2e2, H2a1f, T1a, and U5a1d2b.[31] The Sarmatians examined were found to be closely related to peoples of the earlier Yamnaya culture and to the Poltavka culture.[32]

A genetic study published in Nature in May 2018 examined the remains of twelve Sarmatians buried between 400 BC and 400 AD.[33] The five samples of Y-DNA extracted belonged to haplogroup R1a1, I2b, R (two samples), and R1.[34] The eleven samples of mtDNA extracted belonged to C4a1a, U4a2 (two samples), C4b1, I1, A, U2e1h (two samples), U4b1a4, H28, and U5a1.[35]

A genetic study published in Science Advances in October 2018 examined the remains of five Sarmatians buried between 55 AD and 320 AD. The three samples of Y-DNA extracted belonged to haplogroup R1a1a and R1b1a2a2 (two samples), while the five samples of mtDNA extracted belonged to haplogroup H2a1, T1a1, U5b2b (two samples), and D4q.[36]

A genetic study published in Current Biology in July 2019 examined the remains of nine Sarmatians. The five samples of Y-DNA extracted belonged to haplogroup Q1c-L332, R1a1e-CTS1123, R1a-Z645 (two samples), and E2b1-PF6746, while the nine samples of mtDNA extracted belonged to haplogroup W, W3a, T1a1, U5a2, U5b2a1a2, T1a1d, C1e, U5b2a1a1, U5b2c, and U5b2c.[37]

In a study conducted in 2014 by Gennady Afanasiev, Dmitry Korobov and Irina Reshetova from the Institute of Archaeology of the Russian Academy of Sciences, DNA was extracted from bone fragments found in seven out of ten Alanic burials on the Don River. Four of them turned out to belong to yDNA Haplogroup G2 and six of them possessed mtDNA haplogroup I.[38]

In 2015, the Institute of Archaeology in Moscow conducted research on various Sarmato-Alan and Saltovo-Mayaki culture Kurgan burials. In these analyses, the two Alan samples from the fourth to sixth century AD turned out to belong to yDNA haplogroups G2a-P15 and R1a-z94, while two of the three Sarmatian samples from the second to third century AD were found to belong to yDNA haplogroup J1-M267 while one belonged to R1a.[39] Three Saltovo-Mayaki samples from the eighth to ninth century AD turned out to have yDNA corresponding to haplogroups G, J2a-M410 and R1a-z94.[40]

Appearance[]

In the late second or early third century AD, the Greek physician Galen declared that Sarmatians, Scythians, and other northern peoples had reddish hair.[41] They are said to owe their name (Sarmatae) to that characteristic.[42]

The Alans were a group of Sarmatian tribes, according to the Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus. He wrote that nearly all the Alani were "of great stature and beauty, their hair is somewhat yellow, their eyes are frighteningly fierce".[20]

Greco-Roman ethnography[]

Herodotus (Histories 4.21) in the fifth century BC placed the land of the Sarmatians east of the Tanais, beginning at the corner of the Maeotian Lake, stretching northward for a fifteen-day journey, and adjacent to the forested land of the Budinoi.

Herodotus (4.110–117) recounts that the Sauromatians arose from marriages of a group of Amazons and young Scythian men. In his account, some Amazons were captured in battle by Greeks in Pontus (northern Turkey) near the river Thermodon, and the captives were loaded into three boats. They overcame their captors while at sea, but were not able sailors. The boats were blown north to the Maeotian Lake (the Sea of Azov) onto the shore of Scythia near the cliff region (today's southeastern Crimea). After encountering the Scythians and learning the Scythian language, the Amazons agreed to marry Scythian men, but only on the condition that they move away from the Scythia and not be required to follow the customs of Scythian women. According to Herodotus, the descendants of this band settled toward the northeast beyond the Tanais (Don) river and became the Sauromatians. His account explains the origins of their language as an "impure" form of Scythian. He credits the unusual social freedoms of Sauromatae women, including participation in warfare, as an inheritance from their Amazon ancestors. Later writers refer to the "woman-ruled Sarmatae" (γυναικοκρατούμενοι).[43]

Herodotus (4.118–144) later relates how the Sauromatians, under their king Scopasis, answered the Scythian call for help against the Persian King Darius I, to repel his campaign in Scythia, along with the Gelonians and the Boudinians. The Persians invaded much of the Sauromatian territory, but eventually were forced to withdraw due to the tactics used by the tribespeople, of delay and the use of a scorched earth policy.[44]

Hippocrates[45] explicitly classes them as Scythian and describes their warlike women and their customs:

Their women, so long as they are virgins, ride, shoot, throw the javelin while mounted, and fight with their enemies. They do not lay aside their virginity until they have killed three of their enemies, and they do not marry before they have performed the traditional sacred rites. A woman who takes to herself a husband no longer rides, unless she is compelled to do so by a general expedition. They have no right breast; for while they are yet babies their mothers make red-hot a bronze instrument constructed for this very purpose and apply it to the right breast and cauterize it, so that its growth is arrested, and all its strength and bulk are diverted to the right shoulder and right arm.

Polybius (XXV, 1) mentions them for the first time as a force to be reckoned with in 179 B.C.[18]

Strabo[46] mentions the Sarmatians in a number of places, but never says much about them. He uses both the terms of Sarmatai and Sauromatai, but never together, and never suggesting that they are different peoples. He often pairs Sarmatians and Scythians in reference to a series of ethnic names, never stating which is which, as though Sarmatian or Scythian could apply equally to them all.[47]

Strabo wrote that the Sarmatians extend from above the Danube eastward to the Volga, and from north of the Dnieper River into the Caucasus, where, he says, they are called Caucasii like everyone else there. This statement indicates that the Alans already had a home in the Caucasus, without waiting for the Huns to push them there.

Even more significantly, Strabo points to a Celtic admixture in the region of the Basternae and he notes that they were of Germanic origin. He places the Celtic Boii, Scordisci, and Taurisci there as well as a fourth ethnic element interacting and intermarrying, the Thracians (7.3.2), and moreover, that the peoples toward the north were Keltoskythai, "Celtic Scythians" (11.6.2).

Strabo portrays the peoples of the region as being nomadic, or Hamaksoikoi, "wagon-dwellers", and Galaktophagoi, "milk-eaters". This latter likely referred to the universal kumis eaten in historical times. The wagons were used for transporting tents made of felt, a type of the yurts used universally by Asian nomads.

Pliny the Elder wrote (4.12.79–81):

From this point (the mouth of the Danube) all the races in general are Scythian, though various sections have occupied the lands adjacent to the coast, in one place the Getae... at another the Sarmatae... Agrippa describes the whole of this area from the Danube to the sea... as far as the river Vistula in the direction of the Sarmatian desert... The name of the Scythians has spread in every direction, as far as the Sarmatae and the Germans, but this old designation has not continued for any except the most outlying sections

According to Pliny, Scythian rule once extended as far as Germany. Jordanes supports this hypothesis by telling us on the one hand that he was familiar with the Geography of Ptolemy that includes the entire Balto-Slavic territory in Sarmatia,[citation needed] and on the other that this same region was Scythia. By "Sarmatia", Jordanes means only the Aryan territory. The Sarmatians were, therefore, a sub-group of the broader Scythian peoples.

In his De Origine et situ Germanorum, Tacitus speaks of "mutual fear" between Germanic peoples and Sarmatians:

All Germania is divided from Gaul, Raetia, and Pannonia by the Rhine and Danube rivers; from the Sarmatians and the Dacians by shared fear and mountains. The Ocean laps the rest, embracing wide bays and enormous stretches of islands. Just recently, we learned about certain tribes and kings, whom war brought to light.[48]

According to Tacitus, the Sarmatians wore long, flowing robes similar to the Persians (ch 17). He also noted that the Sarmatians exacted tribute from the Cotini and Osi, and that they exacted iron from the Cotini (ch. 43), "to their shame" (presumably because they could have used the iron to arm themselves and resist).

By the third century BC, the Sarmatian name appears to have supplanted the Scythian in the plains of what now is south Ukraine. The geographer, Ptolemy,[citation needed] reported them at what must be their maximum extent, divided into adjoining European and central Asian sections. Considering the overlap of tribal names between the Scythians and the Sarmatians, no new displacements probably took place. The people were the same Indo-Europeans, but were referred to under yet another name.

Later, Pausanias, viewing votive offerings near the Athenian Acropolis in the second century AD,[49] found among them a Sauromic breastplate.

On seeing this a man will say that no less than Greeks are foreigners skilled in the arts: for the Sauromatae have no iron, neither mined by themselves nor yet imported. They have, in fact, no dealings at all with the foreigners around them. To meet this deficiency they have contrived inventions. In place of iron they use bone for their spear-blades and cornel wood for their bows and arrows, with bone points for the arrows. They throw a lasso round any enemy they meet, and then turning round their horses upset the enemy caught in the lasso. Their breastplates they make in the following fashion. Each man keeps many mares, since the land is not divided into private allotments, nor does it bear any thing except wild trees, as the people are nomads. These mares they not only use for war, but also sacrifice them to the local gods and eat them for food. Their hoofs they collect, clean, split, and make from them as it were python scales. Whoever has never seen a python must at least have seen a pine-cone still green. He will not be mistaken if he liken the product from the hoof to the segments that are seen on the pine-cone. These pieces they bore and stitch together with the sinews of horses and oxen, and then use them as breastplates that are as handsome and strong as those of the Greeks. For they can withstand blows of missiles and those struck in close combat.

The description by Pausanias is well borne out in a relief from Tanais (see image). These facts are not necessarily incompatible with Tacitus, as the western Sarmatians might have kept their iron to themselves, it having been a scarce commodity on the plains.

In the late fourth century, Ammianus Marcellinus[50] describes a severe defeat that Sarmatian raiders inflicted upon Roman forces in the province of Valeria in Pannonia in late 374 AD. The Sarmatians almost destroyed two legions: one recruited from Moesia and one from Pannonia. The latter had been sent to intercept a party of Sarmatians that had been in pursuit of a senior Roman officer named Aequitius. The two legions failed to coordinate, allowing the Sarmatians to catch them unprepared.

Decline begins in the fourth century[]

The Sarmatians remained dominant until the Gothic ascendancy in the Black Sea area (Oium). Goths attacked Sarmatian tribes on the north of the Danube in Dacia, in present-day Romania. The Roman Emperor Constantine I (r. 306–337) summoned his son Constantine II from Gaul to campaign north of the Danube. In 332, in very cold weather, the Romans were victorious, killing 100,000 Goths and capturing Ariaricus, the son of the Gothic king. In their efforts to halt the Gothic expansion and replace it with their own on the north of Lower Danube (present-day Romania), the Sarmatians armed their "servants" Limigantes. After the Roman victory, however, the local population revolted against their Sarmatian masters, pushing them beyond the Roman border. Constantine, on whom the Sarmatians had called for help, defeated the Limigantes, and moved the Sarmatian population back in. In the Roman provinces, Sarmatian combatants enlisted in the Roman army, whilst the rest of the population sought refuge throughout Thrace, Macedonia, and Italy. The Origo Constantini mentions 300,000 refugees resulting from this conflict. Emperor Constantine was subsequently attributed the title of Sarmaticus Maximus.[51]

In the fourth and fifth centuries the Huns expanded and conquered both the Sarmatians and the Germanic tribes living between the Black Sea and the borders of the Roman Empire. From bases in modern-day Hungary, the Huns ruled the entire territory formerly ruled by the Sarmatians. Their various constituents flourished under Hunnish rule, fought for the Huns against a combination of Roman and Germanic troops, and departed after the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains (451), the death of Attila (453), and the appearance of the Bulgar ruling elements west of the Volga.

During the Early Middle Ages, eventually the Proto-Slavic population of Eastern Europe decisively assimilated and absorbed the Sarmatians.[52][53] However, a people related to the Sarmatians, known as the Alans, survived in the North Caucasus into the Early Middle Ages, ultimately giving rise to the modern Ossetic ethnic group.[54]

Legacy[]

Sarmatism[]

Sarmatism (or Sarmatianism) is an ethno-cultural concept with a shade of politics designating the formation of an idea of the origin of Poland from Sarmatians within the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.[55] The dominant Baroque culture and ideology of the nobility (szlachta) that existed in times of the Renaissance to the eighteenth centuries.[55] Together with another concept of "Golden Liberty", it formed a central aspect of the Commonwealth's culture and society. At its core was the unifying belief that the people of the Polish Commonwealth descended from the ancient Iranic Sarmatians, the legendary invaders of Slavic lands in antiquity.[56][57]

Tribes[]

- Alans

- Aorsi

- Arcaragantes

- Hamaxobii (possibly)

- Iazyges

- Limigantes

- Ossetians

- Roxolani

- Serboi

- Siraces

- Spali

- Taifals (possibly)

See also[]

- List of ancient Iranian peoples

- Alans

- Cimmerians

- Early Slavs

References[]

- ^ Unterländer et al. 2017, p. 2. "During the first millennium BCE, nomadic people spread over the Eurasian Steppe from the Altai Mountains over the northern Black Sea area as far as the Carpathian Basin... Greek and Persian historians of the 1st millennium BCE chronicle the existence of the Massagetae and Sauromatians, and later, the Sarmatians and Sacae: cultures possessing artefacts similar to those found in classical Scythian monuments, such as weapons, horse harnesses and a distinctive ‘Animal Style' artistic tradition. Accordingly, these groups are often assigned to the Scythian culture...

- ^ "Sarmatian | people". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ Kozlovskaya, Valeriya (2017). The Northern Black Sea in antiquity : networks, connectivity, and cultural interactions. Kozlovskaya, Valeriya, 1972-. Cambridge, United Kingdom. ISBN 9781108517614. OCLC 1000597862.

- ^ Tarasov, Илья Тарасов / Ilia. "Балты в миграциях Великого переселения народов. Галинды // Исторический формат, № 3-4, 2017. С. 95-124". Балты в миграциях Великого переселения народов. Галинды – via www.academia.edu.

- ^ Brzezinski & Mielczarek 2002, p. 6.

- ^ Bailey, Harold Walter (1985). Khotanese Text. Cambridge University Press. p. 65. ISBN 9780521257794.

- ^ Jump up to: a b (1990), "Podrijetlo imena Hrvat" [The origin of the ethnonym Hrvat], Jezik : Periodical for the Culture of the Standard Croatian Language (in Croatian), 37 (5): 131–133

- ^ Tarasov I. Returning to the theme of ancient migrations of the Galindians // Исторический формат. № 2 (18). 2020. С. 108

- ^ Kuzmina 2007, p. 220.

- ^ Kuzmina 2007, p. 445.

- ^ Kuzmina 2007, p. xiv.

- ^ Kuzmina 2007, p. 50.

- ^ Kuzmina 2007, p. 51.

- ^ Kuzmina 2007, p. 64.

- ^ Kuzmina 2007, p. 78.

- ^ Keyser, Christine; Bouakaze, Caroline; Crubézy, Eric; Nikolaev, Valery G.; Montagnon, Daniel; Reis, Tatiana; Ludes, Bertrand (May 16, 2009). "Ancient DNA provides new insights into the history of south Siberian Kurgan people". Human Genetics. 126 (3): 395–410. doi:10.1007/s00439-009-0683-0. PMID 19449030. S2CID 21347353.

- ^ Barry W. Cunliffe (2001). The Oxford Illustrated History of Prehistoric Europe. Oxford University Press. pp. 402–. ISBN 978-0-19-285441-4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 15. ISBN 978-0-8135-1304-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sinor 1990, p. 113.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Brzezinski & Mielczarek 2002.

- ^ Мошкова М. Г. Памятники прохоровской культуры//САИ, 1963. Д. 1–10

- ^ Уральская историческая энциклопедия. — УрО РАН, Институт истории и археологии. Екатеринбург: Академкнига. Гл. ред. В. В. Алексеев. 2000.

- ^ Граков Б. Н. ГYNAIKOKPATOYMENOI (Пережитки матриархата у сарматов)//ВДИ, 1947. № 3

- ^ Genito, Bruno (1 November 2002). The Elusive Frontiers of the Eurasian Steppes. All’Insegna del Giglio. pp. 57–. ISBN 978-88-7814-283-1.

- ^ Yablonskii, Leonid; Balakhvantsev, Archil (1 January 2009). "A Silver Bowl from the New Excavations of the Early Sarmatian Burial-Ground Near the Village of Prokhorovka". Ancient Civilizations from Scythia to Siberia. 15 (1–2): 167–169. doi:10.1163/092907709X12474657004809.

- ^ "Chemical Analyses of Sarmatian Glass Beads from Pokrovka, Russia" Archived 2005-04-15 at the Library of Congress Web Archives, by Mark E. Hall and Leonid Yablonsky.

- ^ Anthony, David W. (2007). The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-05887-0.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Harmatta 1970, 3.4.

- ^ Handbuch der Orientalistik, Iranistik. By I. Gershevitch, O. Hansen, B. Spuler, M.J. Dresden, Prof M Boyce, M. Boyce Summary. E.J. Brill. 1968.

- ^ Unterländer et al. 2017, Supplementary Information, pp. 55, 72. "Individual I0575 (Sarmatian) belonged to haplogroup R1b1a2a2, and was thus related to the dominant Ychromosome lineage of the Yamnaya (Pit Grave) males from Samara..."

- ^ Unterländer et al. 2017, Supplementary Information, p. 25, Supplementary Table 1.

- ^ Unterländer et al. 2017, pp. 3–4. "The two Early Sarmatian samples from the West... fall close to an Iron Age sample from the Samara district... and are generally close to the Early Bronze Age Yamnaya samples from Samara... and Kalmykia... and the Middle Bronze Age Poltavka samples from Samara..."

- ^ Damgaard et al. 2018, Supplementary Table 2, Rows 19, 21-22, 25, 90-93, 95-97, 116.

- ^ Damgaard et al. 2018, Supplementary Table 9, Rows 15, 18, 64, 67, 68.

- ^ Damgaard et al. 2018, Supplementary Table 8, Rows 57, 79-80, 84, 25-27, 31-33, 59.

- ^ Krzewińska et al. 2018, Supplementary Materials, Table S3 Summary, Rows 4-8.

- ^ Järve et al. 2019, Table S2.

- ^ Reshetova, Irina; Afanasiev, Gennady. "Афанасьев Г.Е., Добровольская М.В., Коробов Д.С., Решетова И.К. О культурной, антропологической и генетической специфике донских алан // Е.И. Крупнов и развитие археологии Северного Кавказа. М. 2014. С. 312-315" – via www.academia.edu. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ дДНК Сарматы, Аланы Google Maps

- ^ Reshetova, Irina; Afanasiev, Gennady. "Афанасьев Г.Е., Вень Ш., Тун С., Ван Л., Вэй Л., Добровольская М.В., Коробов Д.С., Решетова И.К., Ли Х.. Хазарские конфедераты в бассейне Дона // Естественнонаучные методы исследования и парадигма современной археологии. М. 2015. С.146-153" – via www.academia.edu. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Day 2001, pp. 55–57.

- ^ Baumgarten, Siegmund Jakob; Beer, Ferdinand Wilhelm; Semler, Johann Salomo (1760). A Supplement to the English Universal History: Lately Published in London: Containing ... Remarks and Annotations on the Universal History, Designed as an Improvement and Illustration of that Work ... E. Dilly. p. 30.

- ^ Periplus of Pseudo-Scylax, 70; cf. Geographi Graeci minores: Volume 1, p.58

- ^ Herodotus' Histories, book IV

- ^ De Aere XVII

- ^ Strabo's Geography, books V, VII, XI

- ^ J. Harmatta, Studies in the History and Language of the Sarmatians, 1970, ch.1.2

- ^ Germania omnis a Gallis Raetisque et Pannoniis Rheno et Danuvio fluminibus, a Sarmatis Dacisque mutuo metu aut montibus separatur: cetera Oceanus ambit, latos sinus et insularum inmensa spatia complectens, nuper cognitis quibusdam gentibus ac regibus, quos bellum aperuit.

- ^ Description of Greece 1.21.5–6

- ^ Amm. Marc. 29.6.13–14

- ^ Eusebius. "IV.6". Life of Constantine.; *Valois, Henri, ed. (1636) [ca. 390]. "6.32". Anonymus Valesianus I/Origo Constantini Imperatoris.

- ^ Brzezinski & Mielczarek 2002, p. 39.

- ^ Slovene Studies. 9–11. Society for Slovene Studies. 1987. p. 36.

(..) For example, the ancient Scythians, Sarmatians (amongst others), and many other attested but now extinct peoples were assimilated in the course of history by Proto-Slavs.

- ^

Minahan, James (2000). "Ossetians". One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups. Praeger security international. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 518. ISBN 9780313309847. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

The Ossetians, calling themselves Iristi and their homeland Iryston, are the most northerly of the Iranian peoples. [...] They are descended from a division of Sarmatians, the Alans, who were pushed out of the Terek River lowlands and into the Caucasus foothills by invading Huns in the fourth century A.D.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kresin, O. Sarmatism Ukrainian. Ukrainian History

- ^ Tadeusz Sulimirski, The Sarmatians (New York: Praeger Publishers 1970) at 167.

- ^ P. M. Barford, The Early Slavs (Ithaca: Cornell University 2001) at 28.

Sources[]

- Books

- Brzezinski, Richard; Mielczarek, Mariusz (2002). The Sarmatians 600 BC–AD 450. Men-At-Arms (373). Bloomsbury USA; Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-485-6.

- Davis-Kimball, Jeannine; Bashilov, Vladimir A.; Yablonsky, Leonid T. (1995). Nomads of the Eurasian Steppes in the Early Iron Age. Berkeley: Zinat Press. ISBN 978-1-885979-00-1.

- Day, John V. (2001). Indo-European origins: the anthropological evidence. Institute for the Study of Man. ISBN 978-0941694759.

- Hinds, Kathryn (2009). Scythians and Sarmatians. Marshall Cavendish. ISBN 978-0-7614-4519-7.

- Istvánovits, Eszter; Kulcsár, Valéria (2017). Sarmatians: History and Archaeology of a Forgotten People. Schnell & Steiner. ISBN 978-3-7954-3234-8.

- Kozlovskaya, Valeriya (2017). The Northern Black Sea in Antiquity. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-01951-5.

- Kuzmina, Elena Efimovna (2007). The Origin of the Indo-Iranians. BRILL. pp. 50, 51, 56, 64, 78, 83, 220, 410. ISBN 978-90-04-16054-5.

- Sinor, Denis, ed. (1990). The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-24304-9.

- К.Ф. Смирнов. Сарматы и утверждение их политического господства в Скифии. Рипол Классик. ISBN 978-5-458-40072-5.

- Sulimirski, Tadeusz (1970). The Sarmatians. Ancient People and Places, vol. 73. Praeger.

- Journals

- Абрамова, М. П. (1988). "Сарматы и Северный Кавказ". Проблемы сарматской археологии и истории: 4–18.

- Damgaard, P. B.; et al. (May 9, 2018). "137 ancient human genomes from across the Eurasian steppes". Nature. Nature Research. 557 (7705): 369–373. Bibcode:2018Natur.557..369D. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0094-2. PMID 29743675. S2CID 13670282. Retrieved April 11, 2020.

- Genito, Bruno (1988). "The Archaeological Cultures of the Sarmatians with a Preliminary Note on the Trial-Trenches at Gyoma 133: a Sarmatian Settlement in South-Eastern Hungary (Campaign 1985)" (PDF). Annali dell'Istituto Universitario Orientale di Napoli. 42: 81–126.

- Järve, Mari; et al. (July 11, 2019). "Shifts in the Genetic Landscape of the Western Eurasian Steppe Associated with the Beginning and End of the Scythian Dominance". Current Biology. Cell Press. 29 (14): 2430–2441. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.06.019. PMID 31303491.

- Harmatta, J. (1970). "Studies in the History and Language of the Sarmatians". Acta Antique et Archaeologica. XIII.

- Krzewińska, Maja; et al. (October 3, 2018). "Ancient genomes suggest the eastern Pontic-Caspian steppe as the source of western Iron Age nomads". Science Advances. American Association for the Advancement of Science. 4 (10): eaat4457. Bibcode:2018SciA....4.4457K. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aat4457. PMC 6223350. PMID 30417088.

- Клепиков, В. М.; Скрипкин, А. С. (1997). "Ранние сарматы в контексте исторических событий Восточной Европы". Донские древност��. 5: 28–40.

- Козлова, Р. М. (2004). О Сормах, Сарматах, Сорматских горах. Студії з ономастики та етимології (in Ukrainian).

- Lebedynsky, Iaroslav (2002). Les Sarmates: amazones et lanciers cuirassés entre Oural et Danube, VIIe siècle av. J.-C.-VIe siècle apr. J.-C. Errance. ISBN 978-2-87772-235-3.

- Mordvintseva, Valentina I. (2015). "Сарматы, Сарматия и Северное Причерноморье" [Sarmatia, the Sarmatians and the North Pontic Area] (PDF). Вестник древней истории [Journal of Ancient History]. 1 (292): 109–135.

- Mordvintseva, Valentina I. (2013). "The Sarmatians: The Creation of Archaeological Evidence". Oxford Journal of Archaeology. 32 (2): 203–219. doi:10.1111/ojoa.12010.

- Moshkova, M. G. (1995). "A brief review of the history of the Sauromatian and Sarmatian tribes". Nomads of the Eurasian Steppes in the Early Iron Age: 85–89.

- Perevalov, S. M. (2002). "The Sarmatian Lance and the Sarmatian Horse-Riding Posture". Anthropology & Archeology of Eurasia. 40 (4): 7–21. doi:10.2753/aae1061-195940047. S2CID 161826066.

- Rjabchikov, Sergei V. (2004). "Remarks on the Scythian, Sarmatian and Meotian Beliefs". AnthroGlobe Journal.

- Симоненко, А. В.; Лобай, Б. И. (1991). "Сарматы Северо-Западного Причерноморья в I в. н. э.". Погребения знати у с. Пороги (in Russian).

- Unterländer, Martina; et al. (March 3, 2017). "Ancestry and demography and descendants of Iron Age nomads of the Eurasian Steppe". Nature Communications. Nature Research. 8 (14615): 14615. Bibcode:2017NatCo...814615U. doi:10.1038/ncomms14615. PMC 5337992. PMID 28256537.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sarmatians. |

- Yatsenko, S. A. (1992). "CLOTHING vii. Of the Iranian Tribes on the Pontic Steppes and in the Caucaus". CLOTHING vii. Of the Iranian Tribes – Encyclopaedia Iranica. Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. V, Fasc. 7. pp. 758–760.

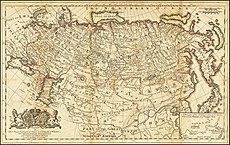

- Ptolemaic Map (Digital Scriptorium)

- Kurgans, Ritual Sites, and Settlements: Eurasian Bronze and Iron Age

- Nomadic Art of the Eastern Eurasian Steppes, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Sarmatians

- Sarmatians

- Historical Iranian peoples

- Bosporan Kingdom

- Peoples of the Caucasus

- Ancient tribes in Ukraine

- Ancient peoples of Ukraine

- Nomadic groups in Eurasia

- Iranian nomads

- History of the western steppe

- History of Eastern Europe

- Tribes in Greco-Roman historiography

- Ancient history of Romania

- History of the Balkans

- History of Ural

- Saltovo-Mayaki culture

- Archaeological cultures of Asia

- Archaeological cultures of Eastern Europe

- Archaeological cultures of Southeastern Europe