Cimmerians

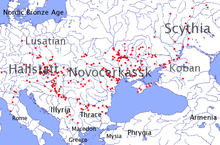

Distribution of "Thraco-Cimmerian" finds. From map in Archaeology of Ukrainian SSR (rus. Археология Украинской ССР) vol. 2, Kiev (1986) | |

| Languages | |

|---|---|

| Cimmerian |

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

The Cimmerians (also Kimmerians; Greek: Κιμμέριοι, Kimmérioi) were a nomadic Indo-European people, who appeared about 1000 BC[1] and are mentioned later in 8th century BC in Assyrian records. While the Cimmerians were often described by contemporaries as culturally "Scythian", they evidently differed ethnically from the Scythians proper, who also displaced and replaced the Cimmerians.[2]

Probably originating in the Pontic-Caspian steppe, the Cimmerians subsequently migrated both into Western Europe and to the south, by way of the North Caucasus.

Some of them likely comprised a force that, c. 714 BC, invaded Urartu, a state subject to the Neo-Assyrian Empire. This foray was defeated by Assyrian forces under Sargon II in 705, after which the same, southern branch of Cimmerians turned west towards Anatolia and conquered Phrygia in 696/5. They reached the height of their power in 652 after taking Sardis, the capital of Lydia; however, an invasion of Assyrian-controlled Anshan was thwarted. Soon after 619, Alyattes of Lydia defeated them. There are no further mentions of them in historical sources, but it is likely that they settled in Cappadocia.

Origins[]

The origin of the Cimmerians is unclear. They are possibly related to either Iranian[3][4][5][6][7] or Thracian[8] speaking groups which migrated under pressure of the Scythian expansion of the 9th to 8th century BC.[9]

According to Herodotus, the Cimmerians inhabited the region north of the Caucasus and the Black Sea during the 8th and 7th centuries BC (i.e. what is now Ukraine and Russia), although they have not been identified with any specific archaeological culture in the region.[10]

Archaeology[]

The origin of the culture is associated with the Belozerskaya culture (12th to 10th centuries) and the later and more certain Novocerkassk (10th to 7th centuries BC) between the Danube and the Volga.[11]

The use of the name "Cimmerian" in this context is due to Paul Reinecke, who in 1925 postulated a "North-Thracian-Cimmerian cultural sphere" (nordthrakisch-kimmerischer Kulturkreis) overlapping with the younger Hallstatt culture of the Eastern Alps. The term Thraco-Cimmerian (thrako-kimmerisch) was first introduced by I. Nestor in the 1930s. Nestor intended to suggest that there was a historical migration of Cimmerians into Eastern Europe from the area of the former Srubnaya culture, perhaps triggered by the Scythian expansion, at the beginning of the European Iron Age. In the 1980s and 1990s, more systematic studies[by whom?] of the artifacts revealed a more gradual development over the period covering the 9th to 7th centuries BC, so that the term "Thraco-Cimmerian" is now rather used by convention and does not necessarily imply a direct connection with either the Thracians or the Cimmerians.[12]

Assyrian records[]

Austen Henry Layard's discoveries in the royal archives at Nineveh and Calah included Assyrian primary records of the Cimmerian invasion.[13] These records appear to place the Cimmerian homeland, Gamir, south (rather than north) of the Black Sea.[14][15][16]

The first record of the Cimmerians appears in Assyrian annals in the year 714 BC. These describe how a people termed the Gimirri helped the forces of Sargon II to defeat the kingdom of Urartu. Their original homeland, called Gamir or Uishdish, seems to have been located within the buffer state of Mannae. The later geographer Ptolemy placed the Cimmerian city of Gomara in this region. The Assyrians recorded the migrations of the Cimmerians, as the former people's king Sargon II was killed in battle against them while driving them from Persia in 705 BC.

The Cimmerians were subsequently recorded as having conquered Phrygia in 696–695 BC, prompting the Phrygian king Midas to take poison rather than face capture. In 679 BC, during the reign of Esarhaddon of Assyria (r. 681–669 BC), they attacked the Assyrian colonies Cilicia and Tabal under their new ruler Teushpa. Esarhaddon defeated them near , and they also met defeat at the hands of his successor Ashurbanipal.

Greek tradition[]

A people named Kimmerioi is described in Homer's Odyssey 11.14 (c. late 8th century BC), as living beyond the Oceanus, in a land of fog and darkness, at the edge of the world and the entrance of Hades.[17]

According to Herodotus (c. 440 BC), the Cimmerians had been expelled from their homeland between the Tyras (Dniester) and Tanais (Don) rivers by the Scythians. Unreconciled to Scythian advances, to ensure burial in their ancestral homeland, the men of the Cimmerian royal family divided into groups and fought each other to the death. The Cimmerian commoners buried the bodies along the river Tyras and fled across the Caucasus and into Anatolia.[18] Herodotus also names a number of Cimmerian kings, including Tugdamme (Lygdamis in Greek; mid-7th century BC), and Sandakhshatra (late-7th century).

In 654 BC or 652 BC – the exact date is unclear – the Cimmerians attacked the kingdom of Lydia, killing the Lydian king Gyges and causing great destruction to the Lydian capital of Sardis. They returned ten years later during the reign of Gyges' son Ardys; this time they captured the city, with the exception of the citadel. The fall of Sardis was a major shock to the powers of the region; the Greek poets Callinus and Archilochus recorded the fear that it inspired in the Greek colonies of Ionia, some of which were attacked by Cimmerian and Treres raiders.[citation needed]

The Cimmerian occupation of Lydia was brief, however, possibly due to an outbreak of disease. They were beaten back by Alyattes.[19] This defeat marked the effective end of Cimmerian power.

The term Gimirri was used about a century later in the Behistun inscription (c. 515 BC) as an Assyro-Babylonian equivalent of Iranian Saka (Scythians).[20] Otherwise, Cimmerians disappeared from the historical record.

Legacy[]

In sources beginning with the Royal Frankish Annals, the Merovingian kings of the Franks traditionally traced their lineage through a pre-Frankish tribe called the Sicambri (or Sugambri), mythologized as a group of "Cimmerians" from the mouth of the Danube river, but who instead came from Gelderland in modern Netherlands and are named for the Sieg river.[21]

Early modern historians asserted Cimmerian descent for the Celts or the Germans, arguing from the similarity of Cimmerii to Cimbri or Cymry. The etymology of Cymro "Welshman" (plural: Cymry), connected to the Cimmerians by 17th-century Celticists, is now accepted by Celtic linguists as being derived from a Brythonic word * kom-brogos, meaning "compatriot".[22] The Cambridge Ancient History classifies the Maeotians as either a people of Cimmerian ancestry or as Caucasian under Iranian overlordship.[23]

The Biblical name "Gomer" has been linked by some to the Cimmerians.[24]

According to Georgian national historiography, the Cimmerians, in Georgian known as Gimirri, played an influential role in the development of the Colchian and Iberian cultures.[25] The modern Georgian word for "hero", გმირი gmiri, is said to derive from their name.[citation needed]

It has been speculated[by whom?] that the Cimmerians finally settled in Cappadocia, known in Armenian as Գամիրք, Gamir-kʿ (the same name as the original Cimmerian homeland in Mannae).[citation needed]

It has also been speculated that the modern Armenian city of Gyumri (Arm.: Գյումրի [ˈgjumɾi]), founded as Kumayri (Arm.: Կումայրի), derived its name from the Cimmerians who conquered the region and founded a settlement there.[26]

Language[]

| Cimmerian | |

|---|---|

| Region | North Caucasus |

| Era | 8th century BC |

Indo-European

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | None (mis) |

08i | |

| Glottolog | None |

Only a few personal names in the Cimmerian language have survived in Assyrian inscriptions:

- Te-ush-pa-a; according to the Hungarian linguist János Harmatta, it goes back to Old Iranian Tavis-paya "swelling with strength".[9] Mentioned in the annals of Esarhaddon, has been compared to the Hurrian war deity Teshub;[citation needed] others interpret it as Iranian, comparing the Achaemenid name Teispes (Herodotus 7.11.2).

- Dug-dam-mei (Dugdammê) king of the Ummân-Manda (nomads) appears in a prayer of Ashurbanipal to Marduk, on a fragment at the British Museum. According to professor Harmatta, it goes back to Old Iranian Duγda-maya "giving happiness".[9] Other spellings include Dugdammi, and Tugdammê. Edwin M. Yamauchi also interprets the name as Iranian, citing Ossetic Tux-domæg "Ruling with Strength."[27] The name appears corrupted to Lygdamis in Strabo 1.3.21.

- Sandaksatru, son of Dugdamme. This is an Iranian reading of the name, and Manfred Mayrhofer (1981) points out that the name may also be read as Sandakurru. Mayrhofer likewise rejects the interpretation of "with pure regency" as a mixing of Iranian and Indo-Aryan. Ivancik suggests an association with the Anatolian deity Sanda. According to Professor J. Harmatta, it goes back to Old Iranian Sanda-Kuru "Splendid Son".[9]

Asimov (1991) attempted to trace various place names to Cimmerian origins. He suggested that Cimmerium gave rise to the Turkic toponym Qırım (which in turn gave rise to the name "Crimea").[28]

Based on ancient Greek historical sources, a Thracian[29][30] or a Celtic[31] association is sometimes assumed.

Genetics[]

A genetic study published in Science Advances in October 2018 examined the remains of three Cimmerians buried between ca. 1,000 BC and 800 BC. The two samples of Y-DNA extracted belonged to haplogroup R1b1a and Q1a1, while the three samples of mtDNA extracted belonged to haplogroup H9a, C5c and R. [32]

A genetic study published in Current Biology in July 2019 examined the remains of three Cimmerians. The two samples of Y-DNA extracted belonged to haplogroup R1a-Z645 and R1a2c-B111, while the three samples of mtDNA extracted belonged to haplogroup H35, U5a1b1 and U2e2.[33]

Timeline[]

- 721–715 BC – Sargon II mentions a land of Gamirr near to Urartu.

- 714 – suicide of Rusas I of Urartu, after defeat by both the Assyrians and Cimmerians.

- 705 – Sargon II of Assyria dies on an expedition against the Kulummu.

- 695 – Cimmerians destroy Phrygia. Death of king Midas.

- 679/678 – Gimirri under a ruler called Teushpa invade Assyria from Hubuschna (Cappadocia?). Esarhaddon of Assyria defeats them in battle.

- 676–674 – Cimmerians invade and destroy Phrygia, and reach Paphlagonia.

- 654 or 652 – Gyges of Lydia dies in battle against the Cimmerians. Sack of Sardis; Cimmerians and Treres plunder Ionian colonies.

- 644 – Cimmerians occupy Sardis, but withdraw soon afterwards

- 637–626 – Cimmerians defeated by Alyattes.

In popular culture[]

Conan the Barbarian, created by Robert E. Howard in a series of fantasy stories published in Weird Tales in 1932, was described as a native Cimmerian, though in Howard's fictional world, his Cimmerians dwelt in a mythological Hyborian Age. The Cimmerians of Hyboria are a pre-Celtic people said by Howard to be the ancestors of the Irish and Scots (Gaels).

If on a winter's night a traveler: The novel by Italo Calvino is a framed presentation of a series of incomplete novels, one of them purported to be translated from the Cimmerian. However, in Calvino's novel, Cimmeria is a fictional country.

The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay: A novel by Michael Chabon has a chapter that talks about the oldest book in the world "The Book of Lo" created by ancient Cimmerians.

See also[]

- List of kings of the Cimmerian Bosporus, including early kings of Cimmeria

References[]

Citations[]

- ^ MacKenzie, David; Curran, Michael W. (2002). A History of Russia, the Soviet Union, and Beyond. Wadsworth/Thomson Learning. p. 12. ISBN 9780534586980.

- ^ Ivanchik, Askold (April 25, 2018). "Scythians". Encyclopædia Iranica.

The Scythian archeological culture embraces not only the Scythians of the East-European steppes, but also the population of the forest steppes, about whose language and ethnic origins it is difficult to say anything precise, and also the Cimmerians

- ^ Tokhtas’ev, Sergei R. (1991). "CIMMERIANS". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. V, Fasc. 6. pp. 563–567.

CIMMERIANS, a nomadic people, most likely of Iranian origin, who flourished in the 8th-7th centuries b.c.e.

- ^ von Bredow, Iris (2006). "Cimmeriin". Brill's New Pauly, Antiquity volumes. doi:10.1163/1574-9347_bnp_e613800.

(Κιμμέριοι; Kimmérioi, Lat. Cimmerii). Nomadic tribe probably of Iranian descent, attested for the 8th/7th cents. BC.

- ^ Liverani, Mario (2014). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. Routledge. p. 604. ISBN 978-0415679060.

Cimmerians (Iranian population)

- ^ J.Harmatta: "Scythians" UNESCO Collection of History of Humanity: Volume III: From the Seventh Century BC to the Seventh Century AD, Routledge/UNESCO. 1996, "The rise of the Scythian kingdom represented an event of intra-ethnic character, since both Cimmerians and Scythians were Iranian peoples." p. 181.

- ^ Kohl, Philip L.; Dadson, D.J., eds. (1989). The Culture and Social Institutions of Ancient Iran, by Muhammad A. Dandamaev and Vladimir G. Lukonin. Cambridge University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0521611916.

Ethnically and linguistically, the Scythians and Cimmerians were kindred groups (both people spoke Old Iranian dialects) (...)

- ^ Frye, Richard Nelson (1984). The History of Ancient Iran. Verlag C.H. Beck. p. 70. ISBN 978-3406093975.

The Cimmerians lived north of the Caucasus mountains in South Russia and probably were related to the Thracians, but they surely were a mixed group by the time they appeared south of the mountains, and we hear of them first in the year 714 B.C. after they presumably had defeated the Urartians

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d J.Harmatta: "Scythians" UNESCO Collection of History of Humanity: Volume III: From the Seventh Century BC to the Seventh Century AD, Routledge/UNESCO. 1996, p. 182

- ^ Renate Rolle, "Urartu und die Reiternomaden", in: Saeculum 28, 1977, 291–339

- ^ Антропологічні особливості давнього населення території України (доба раннього заліза — пізнє середньовіччя), website "Ізборник"

- ^ Ioannis K. Xydopoulos, "The Cimmerians: their origins, movements and their difficulties" in: Gocha R. Tsetskhladze, Alexandru Avram, James Hargrave (eds.), The Danubian Lands between the Black, Aegean and Adriatic Seas (7th Century BC – 10th Century AD), Proceedings of the Fifth International Congress on Black Sea Antiquities (Belgrade – 17–21 September 2013), Archaeopress Archaeology (2015), 119–123. Dorin Sârbu, Un Fenomen Arheologic Controversat de la Începutul Epocii Fierului dintre Gurile Dunării și Volga: 'Cultura Cimmerianã' ("A controversial archaeological phenomenon of the early Iron Age between the mouths of the Danube and the Volga: the Cimmerian Culture"), Romanian Journal of Archaeology (2000) ((in Romanian) online version (with bibliography); English abstract)

- ^ K. Deller, "Ausgewählte neuassyrische Briefe betreffend Urarṭu zur Zeit Sargons II.," in P.E. Pecorella and M. Salvini (eds), Tra lo Zagros e l'Urmia. Ricerche storiche ed archeologiche nell'Azerbaigian Iraniano, Incunabula Graeca 78 (Rome 1984) 97–122.

- ^ Cozzoli, Umberto (1968). I Cimmeri. Rome Italy: Arti Grafiche Citta di Castello (Roma).

- ^ Salvini, Mirjo (1984). Tra lo Zagros e l'Urmia: richerche storiche ed archeologiche nell'Azerbaigian iraniano. Rome Italy: Ed. Dell'Ateneo (Roma).

- ^ Kristensen, Anne Katrine Gade (1988). Who were the Cimmerians, and where did they come from?: Sargon II, and the Cimmerians, and Rusa I. Copenhagen Denmark: The Royal Danish Academy of Science and Letters.

- ^ "Cimmerians" (Κιμμέριοι), Henry Liddell & Robert Scott, Perseus, Tufts University

- ^ Herodotus, Histories, Book 4, sections 11–12.

- ^ Herodotus, 1.16; Polyaenus, 7.2.1, Sergei R. Tokhtas’ev "Cimmerians" in the Encyclopedia Iranica (1991), several nineteenth-century summaries.

- ^ George Rawlinson, noted in his translation of History of Herodotus, Book VII, p. 378

- ^ Geary, Patrick J. Before France and Germany: The Creation and Transformation of the Merovingian World. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988

- ^

- Geiriadur Prifysgol Cymru, vol. I, p. 770.

- Jones, J. Morris. Welsh Grammar: H istorical and Comparative. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995.

- Russell, Paul. Introduction to the Celtic Languages. London: Longman, 1995.

- Delamarre, Xavier. Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise. Paris: Errance, 2001.

- ^ Boardman & Edwards 1991, p. 572

- ^ Robert Drews, Early Riders, 2004, p. 119. He also links them to Gog and Magog.

- ^ Berdzenishvili, N., Dondua V., Dumbadze, M., Melikishvili G., Meskhia, Sh., Ratiani, P., History of Georgia, Vol. 1, Tbilisi, 1958, pp. 34–36

- ^ "Cimmerian". Kumayri infosite. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ Yamauchi, Edwin M (1982). Foes from the Northern Frontier: Invading Hordes from the Russian Steppes. Grand Rapids MI USA: Baker Book House.

- ^ Asimov, Isaac (1991). Asimov's Chronology of the World. New York, NY: HarperCollins. p. 50.

- ^ Meljukova, A. I. (1979). Skifija i Frakijskij Mir. Moscow.

- ^ Strabo ascribes the Treres to the Thracians at one place (13.1.8) and to the Cimmerians at another (14.1.40)

- ^ Posidonius in Strabo 7.2.2.

- ^ Krzewińska et al. 2018, Supplementary Materials, Table S3 Summary, Rows 23-25.

- ^ Järve et al. 2019, Table S2.

Sources[]

- Boardman, John; Edwards, I. E. S. (1991). The Cambridge Ancient History. Volume 3. Part 2. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521227179. Retrieved March 2, 2015.

- Ivanchik A.I. "Cimmerians and Scythians", 2001

- Järve, Mari; et al. (July 11, 2019). "Shifts in the Genetic Landscape of the Western Eurasian Steppe Associated with the Beginning and End of the Scythian Dominance". Current Biology. Cell Press. 29 (14): 2430–2441. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.06.019. PMID 31303491. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- Krzewińska, Maja; et al. (October 3, 2018). "Ancient genomes suggest the eastern Pontic-Caspian steppe as the source of western Iron Age nomads". Science Advances. American Association for the Advancement of Science. 4 (10): eaat4457. Bibcode:2018SciA....4.4457K. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aat4457. PMC 6223350. PMID 30417088.

- Terenozhkin A.I., Cimmerians, Kiev, 1983

- Collection of Slavonic and Foreign Language Manuscripts – St.St Cyril and Methodius – Bulgarian National Library: http://www.nationallibrary.bg/slavezryk_en.html Archived 2009-06-27 at the Wayback Machine

External links[]

| Wikisource has the text of the 1920 Encyclopedia Americana article Cimmerians. |

- Cimmerians by Jona Lendering

- Wiki Classical Dictionary: Cimmerians

- Cimmerians on Regnal Chronologies

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 368.

- Languages with Linglist code

- Cimmerians

- Peoples of the Caucasus

- History of the North Caucasus

- Tribes described primarily by Herodotus

- Indo-European peoples

- Unclassified languages of Asia

- Unclassified Indo-European languages