Ghoul

Ghoul (Arabic: غول, ghūl) is a demon-like being or monstrous humanoid originating in pre-Islamic Arabian religion,[1] associated with graveyards and consuming human flesh. In modern fiction, the term has often been used for a certain kind of undead monster.

By extension, the word ghoul is also used in a derogatory sense to refer to a person who delights in the macabre or whose profession is linked directly to death, such as a gravedigger or graverobber.[2]

Early etymology[]

Ghoul is from the Arabic غُول ghūl, from غَالَ ghāla, "to seize".[3] In Arabic, the term is also sometimes used to describe a greedy or gluttonous individual. See also the etymology of gal and gala: "to cast spells," "scream," "crow," and its association with "warlike ardor," "wrath," and the Akkadian "gallu," which refer to demons of the underworld.

The term was first used in English literature in 1786 in William Beckford's Orientalist novel Vathek,[4] which describes the ghūl of Arabic folklore. This definition of the ghoul has persisted until modern times with ghouls appearing in popular culture.[5]

Folklore[]

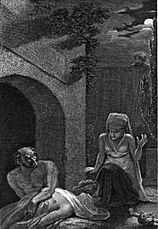

In the Arabic folklore, the ghul is said to dwell in cemeteries and other uninhabited places. A male ghoul is referred to as ghul while the female is called ghulah.[6] A source[who?] identified the Arabic ghoul as a female creature who is sometimes called Mother Ghoul (ʾUmm Ghulah) or a relational term such as Aunt Ghoul.[7] She is portrayed in many tales luring hapless characters, who are usually men, into her home where she can eat them.[7]

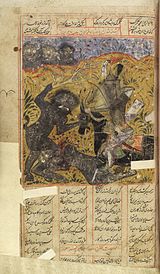

Some state[who?] that a ghoul is a desert-dwelling, shapeshifting demon that can assume the guise of an animal, especially a hyena. It lures unwary people into the desert wastes or abandoned places to slay and devour them. The creature also preys on young children, drinks blood, steals coins, and eats the dead,[8] then taking the form of the person most recently eaten. One of the narratives identified a ghoul named Ghul-e Biyaban, a particularly monstrous character believed to be inhabiting the wilderness of Afghanistan and Iran.[9]

It was not until Antoine Galland translated One Thousand and One Nights into French that the western idea of ghoul was introduced into European society.[citation needed] Galland depicted the ghoul as a monstrous creature that dwelled in cemeteries, feasting upon corpses.

Ghouls (Persian: غول) were also adopted into Iranian folklore.

A ghoul is also a name for a female ghost.

Islamic theology[]

Although not part of Islamic scriptures, some exegete of the Quran report an account of the origin of ghouls. According to one report, the shayatin (devils) once had access to the heavens, where they eavesdropped and returned to Earth to pass hidden knowledge to the soothsayers. When Jesus was born, three heavenly spheres were forbidden to them. With the arrival of Muhammad, the other four were forbidden. The Marid among the shayatin continued to rise to the heavens, but were burned by the comets. If the comets didn't burn them to death, they were deformed and driven to insanity. They then fell to the deserts and were doomed to roam the earth as ghouls.[10]

Others believed the ghoul to be a class of jinn who could be converted to Islam if someone recites the Verse of the Throne.[11]

See also[]

- Lists of legendary creatures

- Bogeyman

- Vrykolakas

- Ghoul (miniseries)

References[]

- ^ Amira El-Zein Islam, Arabs, and Intelligent World of the Jinn Syracuse University Press 2009 ISBN 9780815650706 page 139

- ^ Al-Rawi, Ahmed K. (2009). "The Arabic Ghoul and its Western Transformation". Folklore. 120 (3): 291–306. doi:10.1080/00155870903219730. ISSN 0015-587X. JSTOR 40646532.

- ^ Robert Lebling (30 July 2010). Legends of the Fire Spirits: Jinn and Genies from Arabia to Zanzibar. I.B.Tauris. pp. 96–. ISBN 978-0-85773-063-3.

- ^ "Ghoul Facts, information, pictures | Encyclopedia.com articles about Ghoul". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2011-03-23.

- ^ Al-Rawi, Ahmed K. (11 November 2009). "The Arabic Ghoul and its Western Transformation". Folklore. 120 (3): 291–306. doi:10.1080/00155870903219730.

- ^ Steiger, Brad (2011). The Werewolf Book: The Encyclopedia of Shape-Shifting Beings. Canton, MI: Visible Ink Press. p. 121. ISBN 9781578593675.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Reynolds, Dwight (2015). The Cambridge Companion to Modern Arab Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 260. ISBN 9780521898072.

- ^ "ghoul". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Retrieved January 22, 2006.

- ^ Melton, J Gordon (2010). The Vampire Book: The Encyclopedia of the Undead. Canton, MI: Visible Ink Press. pp. 291. ISBN 9781578592814.

- ^ http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/az-iranian-demon

- ^ Amira El-Zein Islam, Arabs, and Intelligent World of the Jinn Syracuse University Press 2009 ISBN 9780815650706 page 140

- Arabian legendary creatures

- Ghouls