Glyptotherium

| Glyptotherium | |

|---|---|

| |

| G. texanum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Cingulata |

| Family: | Chlamyphoridae |

| Subfamily: | †Glyptodontinae |

| Genus: | †Glyptotherium Osborn 1903 |

| Type species | |

| †Glyptotherium texanum Osborn 1903 | |

| Species | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

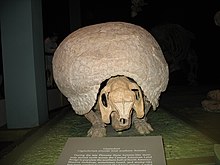

Glyptotherium is an extinct genus of glyptodont, a group of extinct mammals related to the armadillos living from the Middle to Late Pleistocene, approximately 1.8 million to 12,000 years ago (AEO). The genus is considered an example of North American megafauna, of which most have become extinct. Glyptotherium may have been wiped out by changing climate or human interference.[1]

Description[]

Like its living relative, the armadillo, Glyptotherium had a shell which covered its entire body, similar to a turtle. However, unlike the carapace of a turtle, the Glyptotherium shell was made up of hundreds of small hexagonal scales. Some species grew up to 6 feet (1.8 m) long and its armor may have weighed up to a ton.

Paleoecology[]

Remains of Glyptotherium species have been found in tropical and subtropical regions of Venezuela, Panama, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Mexico, and the southern United States; from Florida and South Carolina to Arizona.[3] There is no direct evidence of humans preying on this North American glyptodont. Smilodon may have occasionally preyed upon Glyptotherium, based on a skull from one Glyptotherium fossil recovered from Pleistocene deposits in Arizona bearing the distinctive elliptical puncture marks that best match those of the machairodont cat, indicating that the predator successfully risked biting into bone to kill the armored herbivore, the only option for a predator intent on hunting such heavily armored animals.[4] The Glyptotherium in question was a juvenile, with a still-developing head shield, making it far more vulnerable to the cat's attack.[5] Glyptotherium was named by Osborn in 1903, assigned to Glyptodontinae by Downing and White in 1995 and to Glyptodontidae by Osborn (1903), Brown (1912), Carroll (1988), Cisneros (2005) and Mead et al. (2007).

Gallery[]

Restoration

Juvenile G. texanum skull, possibly attacked by a Smilodon[5]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Glyptotherium cylindricum at Fossilworks.org

- ^ Glyptotherium texanum at Fossilworks.org

- ^ "Glyptotherium Osborn 1903". Paleobiology Database. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ Antón, Mauricio (2013). Sabertooth. Bloomington, Indiana: University of Indiana Press. pp. 203–204. ISBN 9780253010421.

- ^ a b Gillette, D. D. (Spring 2010). "Glyptodonts in Arizona". Arizona Geology. Arizona Geological Survey. Retrieved 2018-08-17.

Further reading[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Glyptotherium. |

- "AMNH Bestiary". Archived from the original on 2006-06-24. Retrieved 2006-06-18.

- , and . 2018. Ectoparasitism and infections in the exoskeletons of large fossil cingulates. PLoS ONE 13. e0205656. Accessed 2018-10-18.

- Prehistoric cingulates

- Prehistoric placental genera

- Pleistocene xenarthrans

- Pleistocene genus extinctions

- Pleistocene mammals of North America

- Blancan

- Irvingtonian

- Lujanian

- Rancholabrean

- Pleistocene Costa Rica

- Fossils of Costa Rica

- Pleistocene El Salvador

- Fossils of El Salvador

- Pleistocene Mexico

- Fossils of Mexico

- Pleistocene Panama

- Fossils of Panama

- Pleistocene United States

- Fossils of the United States

- Pleistocene mammals of South America

- Pleistocene Venezuela

- Fossils of Venezuela

- Fossil taxa described in 1903

- Prehistoric mammal stubs