Graceland Cemetery

Graceland Cemetery | |

U.S. National Register of Historic Places | |

| |

| |

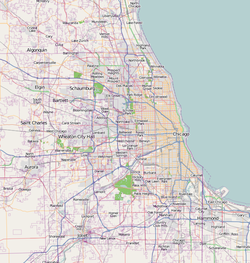

| Location | 4001 N. Clark Street,[2] Chicago, Illinois |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 41°57′16.2″N 87°39′44.2″W / 41.954500°N 87.662278°WCoordinates: 41°57′16.2″N 87°39′44.2″W / 41.954500°N 87.662278°W |

| Area | 119 acres (48 ha) |

| Built | 1860 |

| NRHP reference No. | 00001628[1] |

| Added to NRHP | January 18, 2001 |

Graceland Cemetery is a large historic garden cemetery located in the north side community area of Uptown, in the city of Chicago, Illinois, USA. Established in 1860, its main entrance is at the intersection of Clark Street and Irving Park Road. Among the cemetery's 121 acres are the burial sites of several well-known Chicagoans.[3]

Graceland includes a naturalistic reflecting lake, surrounded by winding pathways, and its pastoral plantings have led it to become a certified arboretum of more than 2,000 trees. The cemetery's wide variety of burial monuments include several designed by famous architects, some of whom are also buried there.[4]

History[]

Thomas Barbour Bryan, a Chicago businessman, established Graceland Cemetery in 1860 with the original 80-acre layout designed by Swain Nelson.[3][5] Bryan's son, Daniel Page Bryan, was the first person to be buried at the cemetery after having been disinterred and removed from the city cemetery in Lincoln Park along with approximately 2,000 other individuals.[6][7] In 1870, Horace Cleveland designed curving paths, open vistas, and a small lake to create a park-like setting.[5] In 1878, Bryan hired his nephew Bryan Lathrop as president. In 1879, the cemetery acquired an additional 35 acres (14 ha), and Ossian Cole Simonds was hired as its landscape architect to design the addition. Lathrop and Simonds wanted to incorporate naturalistic settings to create picturesque views that were the foundation of the Prairie style.[5][7][8] Lathrop was open to new ideas and provided opportunities for experimentation which led to Simonds use of native plants including oak, ash, witch hazel, and dogwood at a time when many viewed native plants as invasive. The Graceland Cemetery Association designated one section of the grounds to be devoid of monuments and instituted a review process led by Simonds for monuments and family plots.[9] Simonds later became the superintendent at Graceland until 1897, and continued on as a consultant until his death in 1931.[5][10]

Graceland Cemetery was added to the National Register of Historic Places on January 18, 2001.[11]

Geography[]

Graceland Cemetery is an example of a rural cemetery, which is a style of cemetery characterized by landscaped natural areas. The concept of the rural cemetery emerged in the early 19th century as a response to overcrowding and poor maintenance in existing cemeteries in Europe.[12]

In the 19th century, a occupied the eastern edge of the cemetery, where the Chicago "L" train now runs. The line was also used to carry mourners to funerals, in specially rented funeral cars. As a result, there was an entry through the east wall, which has since been closed. When founded, the cemetery was well outside the city limits of Chicago. After the Great Chicago Fire in 1871, Lincoln Park, which had been the city's cemetery, was deconsecrated and some of the bodies were reinterred to Graceland Cemetery.[citation needed]

The edge of the pond around Daniel Burnham's burial island was once lined with broken headstones and coping transported from Lincoln Park. Lincoln Park was redeveloped as a recreational area. A single mausoleum remains, the "Couch tomb", containing the remains of Ira Couch.[13] The Couch Tomb is probably the oldest extant structure in the City, everything else having been destroyed by the Great Chicago Fire.[14]

The cemetery's walls are topped off with wrought iron spear point fencing.[citation needed]

Notable tombs and monuments[]

Many of the cemetery's tombs are of great architectural or artistic interest, including the Getty Tomb, the Martin Ryerson Mausoleum (both designed by architect Louis Sullivan, who is also buried in the cemetery), and the Schoenhofen Pyramid Mausoleum. The industrialist George Pullman was buried at night, in a lead-lined coffin within an elaborately reinforced steel-and-concrete vault, to prevent his body from being exhumed and desecrated by labor activists.[citation needed]

William Hulbert, the first president of the National League, has a monument in the shape of a baseball with the names of the original National League cities on it.[15]

Along with its other famous burials, the cemetery is notable for two statues by sculptor Lorado Taft, Eternal Silence for the Graves family plot and The Crusader that marks Victor Lawson's final resting place.

The cemetery is also the final resting place of 33 victims of the Iroquois Theatre fire, in which more than 600 people died.[16]

Notable burials[]

- David Adler, architect[17]

- Walter Webb Allport, dentist[18]

- John Peter Altgeld, Governor of Illinois[19]

- Amabel Anderson Arnold, organized the Woman's State Bar Association of Missouri, the first association of women lawyers in the world[20]

- Philip Danforth Armour, meat packing magnate[19]

- Ernie Banks, Chicago Cubs Hall of Fame baseball player[21]

- Frederic Clay Bartlett, artist, art collector

- Mary Hastings Bradley, author[22]

- Lorenz Brentano, member of the State House of Representatives, United States consul at Dresden, Congressional Representative for Illinois[23]

- Doug Buffone, Chicago Bears former linebacker, host WSCR[24]

- Daniel H. Burnham, architect[25]

- Fred A. Busse, mayor of Chicago[26]

- Justin Butterfield, attorney, land grant developer[27]

- Lydia Avery Coonley, author[28]

- Oscar Stanton De Priest[29] first African American in the 20th century to be elected to Congress.

- William Deering, founder of Deering Harvester Company, which later became International Harvester Company, father of James and Charles Deering[30]

- James Deering, executive of Deering Harvester Company and original owner of the Villa Vizcaya estate

- Charles Deering, executive of Deering Harvester Company, former chairman of International Harvester Company, and philanthropist

- Augustus Dickens, brother of Charles Dickens (he died penniless in Chicago)[22]

- Roger Ebert, film critic (cremated at Graceland Cemetery)

- George Elmslie, architect

- John Jacob Esher (1823–1901), Bishop of the Evangelical Association[31]

- Marshall Field, businessman, retailer, whose memorial was designed by Henry Bacon, with sculpture by Daniel Chester French[32]

- Bob Fitzsimmons, Heavyweight boxing champion, born in Cornwall, UK[33]

- Melville Fuller, Chief Justice of the United States[34]

- Elbert H. Gary, judge, chairman of U.S. Steel

- Bruce A. Goff, architect[25]

- Sarah E. Goode, first African-American woman to receive a United States patent

- Bruce Graham, co-architect of John Hancock building and Sears Tower (now called the Willis Tower)

- Dexter Graves was an early pioneer in the city who arrived on the schooner Telegraph in the 1830s.[35] His memorial by Lorado Taft is the statue Eternal Silence (also known as "the Dexter Graves Monument").

- Richard T. Greener, first black graduate of Harvard (1870), first black professor at the University of South Carolina (1873-1877), administrator for the Ulysses S. Grant Memorial, and diplomat to Russia[36]

- Marion Mahony Griffin, architect[25]

- Carter Harrison, Sr., mayor of Chicago[37]

- Carter Harrison, Jr., mayor of Chicago[38]

- Herbert Hitchcock, US Senator from South Dakota[39]

- William Holabird, architect[40]

- Henry Honoré, businessman, father of Bertha Honoré Palmer, father-in-law of Potter Palmer

- William Hulbert, president of baseball's National League

- Charles L. Hutchinson, banker, philanthropist and founding president of the Art Institute of Chicago

- William Le Baron Jenney, architect, Father of the American skyscraper[25]

- Elmer C. Jensen, "The Dean of Chicago Architects"

- Jack Johnson, first African-American heavyweight boxing champion[41]

- William Johnson, educator who served as superintendent of Chicago Public Schools[42]

- John and Mary Richardson Jones, husband-and-wife abolitionists and activists

- Fazlur Khan, co-architect of John Hancock building and Sears Tower (now called the Willis Tower)[25]

- William Wallace Kimball, Kimball Piano and Organ Company

- John Kinzie, Canadian pioneer, early white settler in the city of Chicago[22]

- Cornelius Krieghoff, well-known Canadian artist

- Bryan Lathrop, businessman, philanthropist, and longtime president of the cemetery[43]

- Robert Henry Lawrence Jr., first African American astronaut (cremated at Graceland, but not physically buried there)

- Victor F. Lawson, editor and publisher of the Chicago Daily News[44]

- Agnes Lee, poet and translator

- Frank Lowden, Governor of Illinois[45]

- Alexander C. McClurg, bookseller and Civil War general

- Cyrus McCormick, businessman, inventor

- Edith Rockefeller McCormick, Daughter-in-law of reaper inventor Cyrus McCormick and one of the four adult children of John D. Rockefeller[22]

- Katherine Dexter McCormick, Daughter-in-law of reaper inventor Cyrus McCormick, MIT grad, biologist, suffragist, philanthropist

- , second wife of Col. Robert R. McCormick[46]

- Nancy "Nettie" Fowler McCormick, businesswoman, philanthropist

- Joseph Medill, publisher, mayor of Chicago[47]

- Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, architect[25]

- László Moholy-Nagy, influential photographer, teacher, and founder of the New Bauhaus and Institute of Design IIT in Chicago[25]

- Dawn Clark Netsch, comptroller of Illinois, professor & spouse of architect Walter Netsch

- Walter Netsch, architect[25]

- Richard Nickel, photographer, architectural historian and preservationist[25]

- Ruth Page, dancer and choreographer[48]

- Bertha Honoré Palmer, philanthropist[32]

- Francis W. Palmer, newspaper printer, U.S. Representative, Public Printer of the United States[49]

- Potter Palmer, businessman[32]

- Richard Peck, author[50]

- Allan Pinkerton, detective[51]

- William Henry Powell, Medal of Honor recipient

- George Pullman, inventor and railway industrialist

- Wilhelm Rapp, newspaper editor

- Hermann Raster, newspaper editor, politician and abolitionist

- John Wellborn Root, architect[52]

- Howard Van Doren Shaw, architect[25]

- , pioneer wholesale grocer and philanthropist.[53] The Washington and Jane Smith Home (now Smith Village) was named in his honor.[54]

- Louis Sullivan, architect[25]

- Charles Wacker, businessman and philanthropist, also director of the 1893 Columbian Exposition[55]

- Kate Warne, first female detective, Allan Pinkerton employee[56]

- Hempstead Washburne, mayor of Chicago[57]

- Daniel Hale Williams, African-American surgeon who performed one of the first successful operations on the pericardium[58]

- , lumber baron.[59] His home, built in 1885, on 2801 S. Prairie Ave. in Chicago, IL is a historical landmark[60]

Other cemeteries in the city of Chicago[]

Graceland is one of three large mid 19th-century Chicago cemeteries which were then well outside the city limits; the other two being Rosehill (further north), and Oak Woods (on the south-side) all in the elaborated pastoral cemetery style.

In addition, directly south of Graceland across Irving Park Road are the smaller German Protestant Wunder's Cemetery, and adjacent Jewish Graceland Cemetery (divided by a fence), established in 1851. The Roman Catholic, Saint Boniface Cemetery (1863), is four blocks north of Graceland at the corner of Clark and Lawrence.

See also[]

- List of mausoleums

- United States National Cemeteries

Notes[]

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ "Graceland Cemetery and Arboretum". gracelandcemetery.org. Retrieved August 1, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Graceland Cemetery". www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org.

- ^ Kamin, Blair. "Column: Graceland Cemetery is an unexpected green oasis, with architecture galore. Don't miss these monuments". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Graceland Cemetery - IL | The Cultural Landscape Foundation". tclf.org. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- ^ Simon, Andreas (1894). Chicago: The Garden City ...

- ^ Jump up to: a b Funigiello, Philip J. (1994). Florence Lathrop Page: A Biography. University of Virginia Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-8139-1489-3.

- ^ Lanctot, Barbara (1988). A Walk Through Graceland Cemetery. Chicago, Illinois: Chicago Architectural Foundation. p. 2.

- ^ Tishler, William H. (2004). Midwestern Landscape Architecture. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-07214-7.

- ^ "O.C. Simonds | The Cultural Landscape Foundation". tclf.org. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- ^ "NPGallery Asset Detail". npgallery.nps.gov. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- ^ Vernon, Christopher (2012). Graceland Cemetery: A Design History. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press. pp. 23–25. ISBN 978-1558499263.

- ^ Dabs. "Chicago Cemeteries". Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- ^ Bannos, Pamela (2012). "The Couch Tomb — Hidden truths: Visualizing the City Cemetery". The Chicago Cemetery & Lincoln Park. Northwestern University. Retrieved November 15, 2012.

- ^ Bojanowski, Mike (October 6, 2016). "A Tour Of The Cubs-Related Graves At Graceland Cemetery". Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- ^ Find A Grave. "Victims of the Iroquois Theatre Fire". Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- ^ "David Adler". David Adler Center for Music and Arts.

- ^ Thorpe, Burton Lee (1910). Koch, Charles R. E. (ed.). History of Dental Surgery. III. Fort Wayne, IN: National Art Publishing Company.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rosenow, Michael (2015). Death and Dying in the Working Class, 1865-1920. University of Illinois Press. p. 49. ISBN 9780252097119. Retrieved September 29, 2017.

- ^ Spencer, Thomas E. (1998). Where They're Buried: A Directory Containing More Than Twenty Thousand Names of Notable Persons Buried in American Cemeteries, with Listings of Many Prominent People who Were Cremated. Genealogical Publishing Com. p. 4. ISBN 9780806348230. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- ^ FOX. "'Mr. Cub' Ernie Banks laid to rest at Graceland Cemetery". fox32chicago.com. Retrieved November 7, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Who in the Dickens is that?". Graceland Cemetery and Arboretum.

- ^ "Brentano, Lorenzo,(1813-1891)".

- ^ "Chicago Says Goodbye To Beloved Bear Doug Buffone". CBS Chicago. CBS Broadcasting Inc. April 24, 2015. Retrieved July 18, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k "The Cemetery of Architects". Graceland Cemetery and Arboretum.

- ^ "Mayor Fred A. Busse Biography". Chicago Public Library. Chicago Public Library. Retrieved September 29, 2017.

- ^ Bannos, Pamela (2012). "Cemetery Lot Owners — Hidden truths: Visualizing the City Cemetery". The Chicago Cemetery & Lincoln Park. Northwestern University. Retrieved July 20, 2018.

- ^ "Mrs. Lydia A. Coonley Ward, Author, Dies". Democrat and Chronicle. February 27, 1924. p. 1. Retrieved November 30, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "DE PRIEST, Oscar Stanton - Biographical Information". bioguide.congress.gov. Retrieved October 31, 2018.

- ^ "William Deering, born in Maine, 1826, died in Florida 1913". eBook from the library of the University of Illinois. 1914. Retrieved July 20, 2018.

- ^ "J.J. Esher, Long a Bishop, Dead". Chicago Tribune. April 16, 1901. Retrieved September 25, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Monuments and their Makers". Graceland Cemetery and Arboretum.

- ^ Wilson, Scott (2016). Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, 3d ed. McFarland. p. 245. ISBN 9781476625997. Retrieved September 29, 2017.

- ^ Zangs, Mary (2014). The Chicago 77: A Community Area Handbook. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9781625851468. Retrieved September 29, 2017.

- ^ Rodkin, Dennis (March 2006). "Why Everybody Loves Naperville". Chicago. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ^ D C McJonathan-Swarm (July 16, 2007). "Richard Theodore Greener, Find A Grave Memorial 20477831". Graceland Cemetery.

- ^ "Mayor Carter Henry Harrison III Biography". Chicago Public Library. Chicago Public Library. Retrieved September 9, 2017.

- ^ "Mayor Carter Henry Harrison IV Biography". Chicago Public Library. Chicago Public Library. Retrieved September 9, 2017.

- ^ "Hitchcock, Herbert Emery, (1867-1958)". Biographical Directory of the United States of Congress.

- ^ AIA Guide to Chicago. University of Illinois Press. May 15, 2014. p. 234. ISBN 978-0252096136.

- ^ Kelder, Robert (January 25, 2005). "Visitors drawn to Jack Johnson's Grave". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved September 29, 2017.

- ^ White, Theresa Mary (1988). "Coping with Administrative Pressures in the Chicago Schools' Superintendency: An Analysis of William Henry Johnson, 1936-1946". Loyola University Chicago. p. 198. Retrieved August 15, 2021.

- ^ "Bryan Lathrop Funeral Held at Graceland Chapel". Chicago Daily Tribune. May 16, 1916. p. 17. Retrieved April 30, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Matt Hucke and Ursula Bielski. Graveyards of Chicago. Lake Claremont Press, 1999. 21.

- ^ "Lowden, Frank Orren(1861-1943)". Biographical Directory of the United States of Congress.

- ^ "Maryland Mathison Hooper McCormick (1897–1985)". Cantigny. Retrieved on June 23, 2012.

- ^ "Mayor Joseph Medill Biography". Chicago Public Library. Chicago Public Library. Retrieved September 29, 2017.

- ^ Hartz, Taylor (October 31, 2017). "Lots of graves – but no ghosts – on Halloween Graceland Cemetery Tour". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved April 29, 2019.

- ^ "Palmer, Francis Wayland, (1827-1907)". Biographical Directory of the United States of Congress.

- ^ Shannon Maughan (May 24, 2018). "Obituary: Richard Peck". Publishers Weekly. PWxyz, LLC. Retrieved July 20, 2018.

- ^ "Allan Pinkerton". National Park Service.

- ^ Lanctot, Barbara (1988). A Walk Through Graceland Cemetery. Chicago: Chicago Architectural Foundation. pp. 14–15.

- ^ Guyer, Isaac D. (1862). History of Chicago – Its Commercial and Manufacturing Interests and Industry. Chicago: Church, Goodman & Cushing, Book and Job Printers. pp. 96–7.

- ^ "$1,000,000 Is Left for Old Folks' Home". Chicago Daily Tribune. March 8, 1923. p. 17. Retrieved April 30, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Lanctot. Barbara, ‘’A Walk Through Graceland Cemetery: A Chicago Architecture Foundation Walking Tour, A Chicago Architecture Foundation Walking Tour, Chicago, IL, 1992 p. 30

- ^ "Public Figures and Private Eyes". Graceland Cemetery and Arboretum.

- ^ "Graceland Cemetery Last Resting Place for Notable Chicagoans". Southern Illinoisan. Carbondale, IL. August 4, 1982. p. P1. Retrieved April 30, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Daniel Hale Williams [1856-1931]". Northwestern University Library University Archives. Northwestern University. Retrieved July 22, 2018.

- ^ "American Lumbermen, Chicago, IL 1906 p. 145". 1906.

- ^ "Chicago's Mansions, Chicago, IL 2004".

Further reading[]

- Hucke, Matt and Bielski, Ursula (1999) Graveyards of Chicago: the people, history, art, and lore of Cook County Cemeteries, Lake Claremont Press, Chicago

- Kiefer, Charles D., Achilles, Rolf, and Vogel, Neil A. "Graceland Cemetery" (PDF), National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, HAARGIS Database, Illinois Historic Preservation Agency, June 18, 2000, accessed October 8, 2011.

- Lanctot, Barbara (1988) A Walk Through Graceland Cemetery, Chicago Architectural Foundation, Chicago, Illinois

- Vernon, Christopher (2012) Graceland Cemetery: A Design History. Amherst, MA: Library of American Landscape History and University of Massachusetts Press.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Graceland Cemetery. |

- 1860 establishments in Illinois

- Cemeteries in Chicago

- Cemeteries on the National Register of Historic Places in Illinois

- National Register of Historic Places in Chicago

- Rural cemeteries