Grand Mufti of Jerusalem

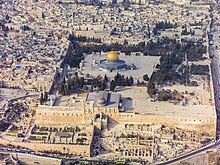

The Grand Mufti of Jerusalem is the Sunni Muslim cleric in charge of Jerusalem's Islamic holy places, including the Al-Aqsa Mosque.[1] The position was created by the British military government led by Ronald Storrs in 1918.[2][3] Since 2006 it has been held by Muhammad Hussein.

History[]

British Mandate[]

While Palestine was under British Mandate, the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem was a position created by the British Mandate authorities.[2] The creation of the new title was intended by the British to "enhance the status of the office".[4]

When Kamil al-Husayni died in 1921, the British High Commissioner Herbert Samuel appointed Mohammad Amin al-Husayni to the position. Amin al-Husayni, a member of the al-Husayni family of Jerusalem, was an Arab nationalist and Muslim leader in the British Mandate of Palestine. As Grand Mufti and leader in the Arab Higher Committee, especially during the war period 1938-45, al-Husayni played a key role in violent opposition to Zionism and closely allied himself with the Nazi regime in Germany.[5][6] In 1948, after Jordan occupied Jerusalem, Abdullah I of Jordan officially removed al-Husayni from the post, banned him from entering Jerusalem, and appointed Hussam Al-din Jarallah as Grand Mufti. On the death of Jarallah in 1952, the Jordan's Jerusalem Islamic Waqf appointed Saad al-Alami as his replacement.[7] The Waqf appointed Sulaiman Ja'abari in 1993, following the death of al-Alami.[8]

Palestinian Authority[]

After Ja'abari's 1994 death, two rival muftis were appointed: the Palestinian Authority (PA) nominated Ekrima Sa'id Sabri, while Jordan named Abdul Qader Abdeen, head of the Religious Appeals Court.[9][10] This reflected a discrepancy between the Oslo I Accord, which envisaged a transfer of authority from Israel to the PA, and the Israel–Jordan peace treaty, which recognised Hashemite custodianship of Jerusalem holy sites.[10] Local Muslims endorsed the PLO's view that Jordan's action was an unwarranted interference; Ja'abari's popular mandate meant that Abdeen's claim "soon faded away altogether"[10] and he formally retired in 1998.[11]

Sabri was removed in 2006 by PA president Mahmoud Abbas, who was concerned that Sabri was involved too heavily in political matters.[12] Abbas appointed Muhammad Ahmad Hussein, who was perceived as a political moderate. However, shortly after his appointment, Hussein made comments which suggested that suicide bombing was an acceptable tactic for Palestinians to use against Israel.[12]

List[]

- Kamil al-Husayni from the creation of the role in 1920 until his death in 1921

- Mohammad Amin al-Husseini from 8 May 1921 to 1948, exiled by the British in 1937 (but not dismissed as Mufti)[13][14]

- Hussam ad-Din Jarallah from 20 December 1948[15]

- Saad al-Alami from 1953 to 6 February 1993[16][17]

- Sulaiman Ja'abari from 17 February 1993 (Jordan) / 20 March 1993 (PA) to 11 October 1994[18]

- Abdul Qader Abdeen (Jordan) from 11 October 1994 to 1998[19]

- Ekrima Sa'id Sabri (PA) from 16 October 1994 to July 2006[19]

- Muhammad Ahmad Hussein from July 2006

See also[]

- Chief Rabbi of Jerusalem

- Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques

- Grand Mufti

- Jerusalem in Islam

- Pro-Jerusalem Society (1918-1926) - the Grand Mufti was a member of its leading Council

Sources[]

- Nazzal, Nafez (1997). Historical dictionary of Palestine. Lanham, Md: Scarecrow. ISBN 978-0-585-21029-2 – via Internet Archive.

Citations[]

- ^ Friedman, Robert I. (2001-12-06). "And Darkness Covered the Land". The Nation. Retrieved 2007-09-13.

- ^ a b See Islamic Leadership in Jerusalem for further details

- ^ The terminology was used as early as 1918. For example: Taysīr Jabārah (1985). Palestinian Leader Hajj Amin Al-Husayni: Mufti of Jerusalem. Kingston Press. ISBN 978-0-940670-10-5. states that Storrs wrote on November 19, 1918 "the Muslim element requested the Grand Mufti to have the name of the Sharif of Mecca mentioned in the Friday prayers as Caliph"

- ^ The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition: Supplement. Brill Archive. 1 January 1980. p. 68. ISBN 90-04-06167-3.

- ^ Pappe, Ilan (2002) 'The Rise and Fall of a Palestinian Dynasty. The Husaynis 1700-1948. AL Saqi edition 2010. ISBN 978-0-86356-460-4. pp.309,321

- ^ Cohen, Aharon (1970) Israel and the Arab World. W.H. Allen. ISBN 0-491-00003-0. p.312

- ^ Obituary: Saad al-Alami

- ^ Blum, Yehuda Z. (1994). "From Camp David to Oslo". Israel Law Review. 28 (2–3): note 20. doi:10.1017/S0021223700011638.

the Mufti of Jerusalem died in the summer of 1994 and the Government of Jordan appointed his successor (as it had done since 1948, including the period since 1967)

[reprinted in Blum, Yehuda Zvi (2016). Will "justice" bring peace? : international law-selected articles and legal opinions. Leiden: Brill. pp. 243–265. doi:10.1163/9789004233959_016. ISBN 9789004233959.] - ^ Rowley, Storer H. Storer (6 November 1994). "Now Muslims Argue Over Jerusalem". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2 October 2021.; Ghazali, Said (6 March 1995). "Activist Mufti Sees Himself as Warrior for Jerusalem". Associated Press. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- ^ a b c Wasserstein, Bernard (2008). "The battle of the muftis". Divided Jerusalem : the struggle for the holy city. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. pp. 338–341. ISBN 978-0-300-13763-7 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Rekhess, Elie (9 May 2008). "The Palestinian Political Leadership in East Jerusalem After 1967". In Mayer, Tamar; Mourad, Suleiman A. (eds.). Jerusalem: Idea and Reality. Routledge. pp. 274–275. ISBN 978-1-134-10287-7.

- ^ a b Yaniv Berman, "Top Palestinian Muslim Cleric Okays Suicide Bombings", Media Line, 23 October 2006.

- ^ An answer in the Commons to a question on notice, given by the Secretary of State for the Colonies:

Mr. Hammersley asked the Secretary of State for the Colonies why no appointment has yet been made to fill the posts of Mufti of Jerusalem and President of the Moslem Supreme Council?

Colonel Stanley. An important distinction must be drawn between the two offices referred to by my hon. Friend. The post of Mufti of Jerusalem is a purely religious office with no powers or administrative functions, and was held by Haj Amin before he was given the secular appointment of President of the Supreme Moslem Council. In 1937 Haj Amin was deprived of his secular appointment and administrative functions, but no action was taken regarding the religious office of Mufti, as no legal machinery in fact exists for the formal deposition of the holder, nor is there any known precedent for such deposition. Haj Amin is thus technically still Mufti of Jerusalem, but the fact that there is no intention of allowing Haj Amin, who has openly joined the enemy, to return to Palestine in any circumstances clearly reduces the importance of the technical point. - ^ Zvi Elpeleg's "The Grand Mufti", page 48: "officially he now retained only the title of Mufti (following the Ottoman practice, this had been granted for life)"

- ^ Nazzal 1997 p.xxiii

- ^ Nazzal 1997 pp. p.34

- ^ "Saad al-Alami Dead; Jerusalem Cleric, 82". The New York Times. 1993-02-07. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2015-10-22.

- ^ Nazzal 1997 pp. xlix, 110

- ^ a b Nazzal 1997 p.lvii

- Grand Muftis of Jerusalem

- Lists of Islamic religious leaders