Grant's Tomb

General Grant National Memorial | |

U.S. National Register of Historic Places | |

U.S. National Memorial | |

New York City Landmark

| |

Grant's Tomb at dusk | |

Location of Grant's Tomb in New York City | |

| Location | Riverside Drive and West 122nd Street, Morningside Heights, Manhattan, New York City |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°48′48″N 73°57′47″W / 40.81333°N 73.96306°WCoordinates: 40°48′48″N 73°57′47″W / 40.81333°N 73.96306°W |

| Area | 0.76 acre (3100 m²) |

| Built | April 27, 1897 |

| Architect | John H. Duncan |

| Architectural style | Neoclassical |

| Visitation | 80,046 (2005) |

| Website | General Grant National Memorial |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000055[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966 |

| Designated NMEM | August 14, 1958 |

| Designated NYCL | November 25, 1975[2] |

| ||

|---|---|---|

American Civil War

18th President of the United States

Presidential elections

Post-presidency

|

||

Grant's Tomb, officially the General Grant National Memorial, is the final resting place of Ulysses S. Grant, 18th President of the United States, and his wife, Julia Grant. It is a classical domed mausoleum in the Morningside Heights neighborhood of Upper Manhattan in New York City. The structure is in the middle of Riverside Drive at 122nd Street, across from Riverside Church to the southeast and Riverside Park to the west.

Upon Grant's death in 1885, his widow declared he had wished to be buried in New York, and a new committee, the Grant Monument Association, appealed for funds. Progress was slow at first, since many believed the tomb should be in Washington, D.C., and because there was no architectural design to show. Eventually they selected a proposal by John Hemenway Duncan for a tomb of "unmistakably military character," modeled after the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, with twin sarcophagi based on Napoleon’s tomb at Les Invalides. The tomb was completed in 1897, and the National Park Service has managed it since 1958. After a period of neglect, it has been restored and rededicated.

The mausoleum is a prominent architectural land feature visible from the Hudson River. Grant's Tomb is generally open to the public from Wednesdays through Saturdays. In addition to being a national memorial since 1958, Grant's Tomb was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1966 and was designated an official New York City landmark in 1975.

History[]

Creation of Grant Monument Association[]

On July 23, 1885, Grant died of throat cancer at age 63 in Wilton, New York. Within hours of Grant's death, William Russell Grace, the Mayor of New York City, sent a telegram to Julia offering New York City to be the burial ground for both Grant and Julia. Grant's only real wish when he died was to be next to his wife when he was buried. In practice this eliminated all military cemeteries and installations (such as West Point) from consideration, as they did not permit women to be interred at the time.[3] Grant's family agreed to have his remains interred in New York City.[4] Grace wrote a letter to prominent New Yorkers the following day, to gather support for a national monument in Grant's honor:[4]

Dear Sir: In order that the City of New York, which is to be the last resting place of General Grant, should initiate a movement to provide for the erection of a National Monument to the memory of the great soldier, and that she should do well and thoroughly her part, I respectfully request you to as one of a Committee to consider ways and means for raising the quota to be subscribed by the citizens of New York City for this object, and beg that you will attend a meeting to be held at the Mayor's office on Tuesday next, 28 inst., at three o'clock ...[4]

The preliminary meeting was attended by 85 New Yorkers who established the Committee on Organization. Its chairman was former President Chester A. Arthur; its secretary was Richard Theodore Greener. The organization would come to be known as the Grant Monument Association (GMA).[5]

Funding[]

The Grant Monument Association did not originally announce the function or structure of the monument; however, the idea of any monument in Grant's honor drew public support.[5] Western Union donated $5,000 on July 29, the day the committee announced its proposal.[5] The GMA continued to receive donations of large and small amounts. At a membership meeting, former New York State governor Alonzo Cornell proposed a fundraising goal of $1 million.[6] Private industries such as insurance and iron-trading companies donated funds to the project. For every ton of coal the Consumers Coal Company sold, it gave a major donation of 37½ cents to the GMA.[7] Although there was great enthusiasm for a monument to President Grant, early fundraising efforts were stifled by growing negative public opinion expressed by out-of-state press.[8] The Clay County Enterprise in Brazil, Indiana, wrote, "We have not a cent for New York in the undertaking, and would advise that not a dollar of help be sent to the millionaire city from Indiana ... If the billions of New York are not sufficient to embellish the city ... let the remains be placed in Washington or some other American city." (September 11)[8]

The opposition was vocal in the view that the monument should be in Washington, D.C. Mayor Grace tried to calm the controversy by publicly releasing Mrs. Grant's justification for the New York site as the resting place for her husband:

Riverside was selected by myself and my family as the burial place of my husband, General Grant. First, because I believed New York was his preference. Second, it is near the residence that I hope to occupy as long as I live, and where I will be able to visit his resting place often. Third, I have believed, and am now convinced, that the tomb will be visited by as many of his countrymen there as it would be at any other place. Fourth, the offer of a park in New York was the first which observed and unreservedly assented to the only condition imposed by General Grant himself, namely, that I should have a place by his side.[9]

Criticism was not limited to the debate about the monument's location. According to The New York Times, there was discontent with the internal management of the GMA. Even though the GMA members were among the wealthiest in New York, they were making comparatively small donations to the effort they themselves were promoting. The New York Times characterized the members as "sitting quietly in an office and signing receipts for money voluntarily tendered."[10] In this early stage, the GMA did not have a model for what the monument was to be; it continued to ask for donations without explaining its purpose, which frustrated and discouraged donors.[11] Joan Waugh captured the feelings of the average citizen in her book, American Hero American Myth: "Why should citizens give money to build a monument whose shape was still a mystery?"[12] The GMA did not propose a definitive plan for the monument until five years later.[13] During its first few years, the GMA fell short of the fundraising expectations originally set by Alonzo Cornell. In the first year, 1885, the GMA raised just over $111,000, 10% of its goal. In the two years that followed, it raised just $10,000. The slow pace of fundraising caused some trustees to resign. No design for the structure yet existed, and without such a design, it was believed that fundraising efforts would continue to remain low.[citation needed]

Design competition[]

On February 4, 1888, after a year's delay, the GMA publicly announced the details of a design competition, in a newsletter entitled "To Artists, Architects, and Sculptors".[14] This information was made public to the entire nation; it was also published in Europe.[14] The GMA also proposed a new estimate for the monument's cost, which ranged from $500,000 to $1 million.[14] The deadline for all designs was rescheduled three times and was then set for a final date of January 10, 1889.[15]

The first design competition received 65 designs, 42 of which came from international entries. The Grant Memorial Association did not award an overall winner, and a second design competition was ordered. In April 1890, the Grant Memorial Association selected, from only five commissioned entries, the design of John Hemenway Duncan,[16] who estimated his design would cost between $496,000 and $900,000.[17] Duncan made his first architectural claims in 1883, designing the Washington Monument at Newburgh, the Newburgh Monument, and the Tower of Victory. Duncan built these structures to celebrate the centennial anniversary of the U.S. Revolutionary War,[18] and he became a member of the Architectural League in 1887.[19] Duncan cited as his design's objective: "to produce a monumental structure that should be unmistakably a tomb of military character."[16] He wanted to avoid "resemblance of a habitable dwelling"[20] as the structure was meant to be the epitome of reverence and respect.[17] The tomb's granite exterior is modeled after the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus with Persian elements[21] and but for the Ionic order of the exterior rotunda columns and the Doric columns of the porch, it resembles the Tropaeum Alpium. Within the tomb, the twin sarcophagi of Grant and his wife Julia are based on the sarcophagus of Napoleon Bonaparte at Les Invalides.[22]

Construction[]

By 1890, the GMA had a defined design and architect. Although the GMA was becoming more organized and the reality of the monument was becoming clearer, the debate over the monument's location reopened in Congress. In October 1890, U.S. Senator Hale introduced legislation to have the sarcophagi placed at a monument in Washington, DC.[23] The legislation did not pass, but the effort reopened the debate over the proper place for the remains of Grant. A groundbreaking ceremony had already been scheduled for April 27, 1891, and although the parties had not agreed on a location for the monument by that date, a groundbreaking ceremony was still held.[24] In June 1891, deliberations ended; the monument was to be built in New York City, and that month, the GMA hired a contractor named John T. Brady.[25]

Construction began that summer, and by August, preliminary excavation was complete.[26] Construction was on schedule until the GMA asked Duncan to alter his design in the spring of 1892; the design could not be as elaborate as originally planned because of the Association's inability to raise the sufficient funds.[27] Construction was also slowed by a stonecutters' strike in 1892. After 1894, construction proceeded at a faster pace, and by 1896, work on the outside of the tomb was nearly complete.[28] One innovative feature of the tomb construction is the use of Guastavino tile vaulting to support the circular floor above the perimeter of the downstairs atrium.

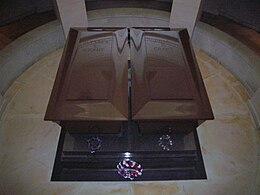

On April 17, 1897, Grant's remains were quietly transferred to an 8.5-ton red granite sarcophagus and placed in the mausoleum. The monument was dedicated ten days later on April 27, 1897, on the 75th-anniversary ceremony of Grant's birth on April 27, 1822.[29] Julia Dent Grant, Grant's wife of nearly 40 years, died five years later in 1902 and was placed in a matching sarcophagus and laid to rest in the mausoleum beside her husband.[30] The sarcophagi are placed above ground, leading to a common riddle by comedian Groucho Marx, who often asked contestants on his radio and television quiz show You Bet Your Life: "Who was buried in Grant's Tomb?" The riddle is based on the use of the word "buried", and since neither of the Grants' tombs are underground, the correct answer is "no one". However, Marx often accepted the answer "Grant" and awarded a consolation prize to those who gave it. He used the question, among several other easy ones, to ensure that everyone won a prize on the show.[31]

Decay and restoration[]

1930s restoration[]

The initial restoration project began in December 1935 (38 years after the tomb opened), when Works Progress Administration laborers installed new marble flooring in the atrium.[32] The WPA played a large role in sustaining the monument. Joan Waugh explains that "In the 1930s the tomb was barely maintained by funds from the Works Progress Administration." Shortly after the restoration project began, the old New York City Post Office was being demolished and donated two statues of eagles to decorate the front of the Grant Monument. The laborers of the WPA worked on several projects throughout the 1930s, including roof restoration, electric lighting and heating systems, and removing the purple stained glass windows. The Pittsburgh Plate Glass Company installed amber glass to replace the purple stained glass. Toward the end of the 1930s, a project began to restore the two reliquary rooms, where battle flags were displayed in trophy cases, and murals of a map in each marked Civil War battles. In 1938, the Federal Art Project selected artists William Mues and Jeno Juszko to design the busts of William T. Sherman, Phillip H. Sheridan, George H. Thomas, James B. McPherson, and Edward Ord.[33] The WPA installed five busts in the circular wall of the atrium surrounding the sarcophagi. After the many contributions of the WPA, the Grant Monument Association held a re-dedication of the tomb on April 27, 1939.[34]

NPS control[]

In 1958, the National Park Service (NPS) was granted authority to oversee the monument. According to an NPS report, an historian admitted that when the NPS first assumed authority over the tomb, they "had no program for the site." Combined with the mismanagement and devastation that New York City was going through financially in the 1960s to the 1990s, that led to great neglect of the site, particularly in the maintenance of the monument.[35]

By the 1970s, the tomb was marred by vandalism and graffiti. Many places in the city, including Times Square, were in the same condition. Trash had heaped up around the monument, its exterior recesses were being used by drug users, the homeless, and criminals for hideouts. Graffiti covered the walls and pedestals, and vandals chipped away at the masonry. The NPS undertook a plan to remove the trophy cases in the reliquary rooms.[35]

1990s restoration[]

The abuse of the monument continued until renewed restoration efforts began in the early 1990s; in 1991, Frank Scaturro, a student at Columbia University and volunteer with the NPS, launched an effort to restore the tomb and brought his concerns to Congress. The tomb was still marred by graffiti and, at the time, there were only three maintenance workers and three rangers on daytime duty, with a yearly budget of $235,000.[35] For over two years, Scaturro battled the National Park Service, which was charged with maintaining Grant's Tomb. He sent weekly memos, including a 26-page report in the summer of 1992.[36] After two years of unsuccessful attempts to navigate the bureaucracy of the National Park Service, Scaturro published a 325-page whistleblower report, which he sent to Congress and the President.[37] Scaturro's efforts drew national media attention and resulted in a $1.8 million grant to restore Grant's Tomb.[37] According to Mr. Scaturro "whistle-blowing was the last resort." Scaturro stated "I only did what I did because I had no other resort ... the only thing left was abandoning the site and that was not an alternative to me."[37] The tomb was in great need of renovation. A New York Times article articulated Mr. Scaturro's concerns, saying "improvements have detracted from the tomb's solemnity."[35]

Scaturro's efforts to expose the monument's poor condition caught the attention of two Illinois state lawmakers. State Sen. Judy Baar Topinka and State Rep. Ron Lawfer sponsored a resolution to compel the National Park Service to meet its obligations in maintaining and restoring Grant's tomb. If the NPS did not comply, then Topinka and Lawfer demanded that Grant's remains be transported to the state of Illinois. Senator Topinka said, "He would be better off anywhere than New York, but my argument is not with New York; it's with the National Park Service."[38]

The demands for restoration did not stop at the state level. In 1994, the U.S. House of Representatives introduced legislation to "restore, complete, and preserve in perpetuity the Grant's Tomb National Memorial and surrounding areas." The legislation set by the House required that the restoration be completed by April 27, 1997, the tomb's 100th anniversary and Grant's 175th birthday.[39] On April 27, 1997, the restoration effort sanctioned by Congress was completed and the tomb re-dedicated.[35] General Grant's descendants, who were appalled by the conditions of the tomb, called Scaturro a hero for his efforts.[40]

Access and policies[]

The visitor center is located about 100 yards to the west of the mausoleum and contains a bookstore, memorabilia, movie about Grant's life, and restrooms. The visitor center of General Grant National Memorial is accessible to people with disabilities, but the mausoleum is not.[41] Generally, both are open Wednesday through Sunday, year-round; the visitor center is open from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. while the tomb is open from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.[42] However, during the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City in 2020 and 2021, opening hours were restricted and part of the memorial was closed to the public.[43]

Photography is allowed in the tomb, but cellphone use, eating, drinking, smoking, and gum chewing are prohibited. Flash photography is discouraged inside the tomb.

The M5 bus stops on either side of Grant's Tomb. The M4 and M104 bus routes run one block east, on Broadway, while the M11 and M60 bus lines run two blocks east, on Amsterdam Avenue. In addition, the 1 train of the New York City Subway stops at 125th Street and Broadway.[44][45]

Activities[]

Events[]

Concerts are regularly held at or right outside Grant's Tomb. Examples include Jazzmobile, Inc.'s annual Free Outdoor Summer Mobile Concerts at Grant's Tomb[46] and the annual Grant's Tomb Summer Concert, which in 2009 featured West Point's United States Military Academy Band.[47] Every year on April 27, the anniversary of Grant's birth, a ceremony celebrating his life is held at the memorial.[48]

Art[]

A sculpture consisting of seventeen concrete benches bearing colorful mosaics was created around the monument in the early 1970s. The sculpture, entitled The Rolling Bench, was designed by artist and the architect Phillip Danzig, and was built with the help of hundreds of neighborhood children over a period of three years.[49] The project was sponsored by CITYarts, a non-profit organization founded in 1968 to create works of public art by bringing together children and artists. The sculpture underwent restoration during the summer of 2008 under the supervision of Silva.[50]

According to NYC Parks, "some popular local folk art in Riverside Park contrasts strikingly with the Tomb's severity".[51]

See also[]

- Presidential memorials in the United States

- Bibliography of Ulysses S. Grant

References[]

Notes

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ "General Grant National Memorial" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. November 25, 1975. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- ^ Kahn 1980, p. 5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Kahn 1980, p. 28.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Kahn 1980, p. 29.

- ^ Kahn 1980, p. 31.

- ^ Kahn 1980, p. 32.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kahn 1980, p. 33.

- ^ Kahn 1980, p. 12.

- ^ Kahn 1980, p. 35.

- ^ Kahn 1980, p. 36.

- ^ Waugh 2009, p. 281.

- ^ Kahn 1980, p. 37.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Kahn 1980, p. 51.

- ^ Kahn 1980, p. 54.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kahn 1980, p. 76.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kahn 1980, p. 77.

- ^ Kahn 1980, p. 73.

- ^ Kahn 1980, p. 74.

- ^ Kahn 1980, p. 78.

- ^ Grgetic, Rick. "Grant's Tomb". Clermont County Ohio Historical Society. Retrieved July 8, 2015.

- ^ Dolkart, Andrew; Postal, Matthew A. (2004). Guide to New York City Landmarks. New York City: Landmarks Preservation Commission. ISBN 9780471369004. Retrieved October 11, 2010.

- ^ Kahn 1980, p. 92.

- ^ Kahn 1980, p. 95.

- ^ Kahn 1980, p. 96.

- ^ Kahn 1980, p. 99.

- ^ Kahn 1980, p. 102.

- ^ Kahn 1980, p. 123.

- ^ Waugh 2009, p. 162.

- ^ "Julia Boggs Dent Grant (1826-1902)". findagrave.com. Find A Grave. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- ^ Marx, Arthur (1960). Life with Groucho. New York: Popular Library Edition, 1960

- ^ Kahn 1980, p. 164.

- ^ Kahn 1980, p. 167.

- ^ Kahn 1980, p. 174.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "The Tomb's Decline and Restoration". grantstomb.org. Grant Monument Association. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved July 8, 2015.

- ^ Norimitsu, Onishi (April 28, 1997). "Ceremony at Grant's Tomb Notes Gadfly's Triumph". The New York Times. Retrieved December 28, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Colimore, Edward (February 16, 1995). "Grave Mission Frank Scaturro, A Longtime Fan Of Gen. Ulysses Grant, Was Appalled To Discover The Low Estate To Which Grant's Famed Tomb Had Fallen. So He Mounted A Campaign To Set Things Right". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved December 28, 2013.

- ^ Howell, David (March 31, 1994). "Lawmakers: Fix Grant's Tomb or Bring it Here". The State Journal-Register. Springfield, Illinois. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved July 8, 2015.

- ^ Grant's Tomb National Memorial Act of 1994, H.R. 4393, 103d Cong., 2nd session (May 11, 1994).

- ^ Green, Jorie (September 22, 1993). "Law student crusades for Grant's Tomb". The Daily Pennsylvanian. Retrieved December 28, 2013.

- ^ "Accessibility". General Grant National Memorial (U.S. National Park Service). April 29, 2013. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ^ "Basic Information". General Grant National Memorial (U.S. National Park Service). June 26, 2019. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ^ "Operating Hours & Seasons - General Grant National Memorial (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ "Manhattan Bus Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. July 2019. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ "Public Transportation - General Grant National Memorial (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ^ "Programs: Summerfest". Jazzmobile.

- ^ "Grant's Tomb: SUMMER CONCERT". GrantsTomb.org. August 28, 2009. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- ^ Drive, Mailing Address: Riverside; York, W. 122nd Street New; Us, NY 10027 Phone:670-7251 Contact. "General Grant National Memorial (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved August 1, 2019.

- ^ Allon, Janet (March 30, 1997). "Mosaic benches face unseating at-Grant's Tomb". The New York Times. Retrieved March 14, 2010.

- ^ Akasie, Jay (August 27, 2008). "Teaching Children the Benefits of Restoration". The New York Sun. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- ^ "Riverside Park Virtual Tour 2) Grant's Tomb". NYC Parks.

Bibliography

- Kahn, David (January 1980). General Grant National Memorial Historical Resource Study. Manhattan Cites.

- Waugh, Joan (2009). U. S. Grant: American Hero, American Myth. North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-3317-9.

Further reading

- The National Parks: Index 2001–2003. Washington: U.S. Department of the Interior.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Grant's Tomb. |

- Official NPS website: General Grant National Memorial

- Other than President U.S. Grant, who rests in Grant’s tomb?[permanent dead link]

- Grant Monument Association

- Grant's funeral and the mausoleum

- Description of The Rolling Bench

- CITYarts project to restore The Rolling Bench

- "Life Portrait of Ulysses S. Grant", from C-SPAN's American Presidents: Life Portraits, broadcast from the General Grant National Memorial, July 12, 1999

- 1897 establishments in New York (state)

- 1897 sculptures

- Biographical museums in New York City

- Buildings and monuments honoring American presidents in the United States

- Buildings and structures completed in 1897

- Government buildings on the National Register of Historic Places in Manhattan

- History museums in New York City

- Mausoleums in the United States

- Mausoleums on the National Register of Historic Places

- Monuments and memorials in Manhattan

- Monuments and memorials on the National Register of Historic Places in New York City

- Morningside Heights, Manhattan

- Museums in Manhattan

- National Memorials of the United States

- National Park Service National Monuments in New York City

- New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan

- New York City interior landmarks

- Presidential museums in New York (state)

- Riverside Park (Manhattan)

- Tombs of presidents of the United States

- Tourist attractions in Manhattan

- Ulysses S. Grant