Great Canadian flag debate

The Great Canadian flag debate (or Great Flag Debate) was a national debate that took place in 1963 and 1964 when a new design for the national flag of Canada was chosen.[1]

Although the flag debate had been going on for a long time prior, it officially began on June 15, 1964, when Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson proposed his plans for a new flag in the House of Commons. The debate lasted more than six months, bitterly dividing[2] the people in the process. The debate over the proposed new Canadian flag was ended by closure on December 15, 1964. It resulted in the adoption of the "Maple Leaf" as the Canadian national flag.

The flag was inaugurated on February 15, 1965, and since 1996, February 15 has been commemorated as National Flag of Canada Day.

Background[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2017) |

Union Jack and Red Ensign[]

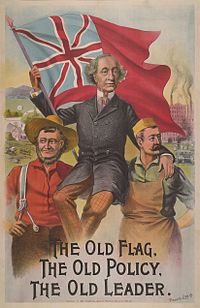

For much of its post-Confederation history, Canada used both the Royal Union Flag (Union Jack) as its national flag, and the Canadian Red Ensign as a popularly recognized and distinctive Canadian flag.

The first Canadian Red Ensigns were used in Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald's time. The Governor General at the time of Macdonald's death, Lord Stanley, wrote to London in 1891:

... the Dominion Government has encouraged by precept and example the use on all public buildings throughout the provinces of the Red Ensign with the Canadian badge on the fly... [which] has come to be considered as the recognized flag of the Dominion, both ashore and afloat.

Under pressure from pro-imperial public opinion, Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier raised the Union Flag over Parliament, where it remained until the re-emergence of the Red Ensign in the 1920s. In 1945, Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, having flown the Union Jack over Parliament throughout the war, made the Canadian Red Ensign the official Canadian flag by Order in Council. Mackenzie King also tried to give Canada a new flag. The recommendation that came back was a Red Ensign, but substituting the coat of arms of Canada with a gold maple leaf. Mackenzie King stopped the venture.

In 1958, an extensive poll was taken of the attitudes that adult Canadians held toward the flag. Of those who expressed opinions, over 80% wanted a national flag entirely different from that of any other nation, and 60% wanted their flag to bear the maple leaf.[3]

Lester B. Pearson[]

From his office as leader of the opposition, Lester Pearson issued a press release on January 27, 1960, in which he summarized the problem and presented his suggestion as:

... Canadian Government taking full responsibility as soon as possible for finding a solution to the flag problem, by submitting to Parliament a measure which, if accepted by the representatives of the people in Parliament, would, I hope, settle the problem.

The Progressive Conservative government of the time, headed by Prime Minister John Diefenbaker, did not accept the invitation to establish a new Canadian flag, so Pearson made it Liberal Party policy in 1961, and part of the party's election platform in the 1962 and 1963 federal elections. During the election campaign of 1963, Pearson promised that Canada would have a new flag within two years of his election. No previous party leader had ever gone as far as Pearson did, by putting a time limit on finding a new national flag for Canada. The 1963 election brought the Liberals back to power, but with a minority government. In February 1964, a three-leaf design was leaked to the press.

At the 20th Royal Canadian Legion Convention in Winnipeg on May 17, 1964, Pearson faced an unsympathetic audience of Canadian Legionnaires and told them that the time had come to replace the Canadian Red Ensign with a distinctive maple leaf flag.[5] The Royal Canadian Legion and the Canadian Corps Association wanted to make sure that the new flag would include the Union Flag as a sign of Canadian ties to the United Kingdom and to other Commonwealth countries, such as Australia and New Zealand, that use the Union Flag in the quarter of their national flag.

Lester Pearson's preferred choice for a new flag was nicknamed "the Pearson Pennant". Pearson’s first design featured the three maple leaves on a white background, with vertical blue bars to either side. Pearson preferred this choice, as the blue bars reflected Canada's motto, "From Sea to Sea".

Parliamentary debate begins[]

Opening resolution[]

On June 15, 1964, Pearson opened the parliamentary flag debate with a resolution:

… to establish officially as the flag of Canada a flag embodying the emblem proclaimed by His Majesty King George V on November 21, 1921 — three maple leaves conjoined on one stem — in the colours red and white then designated for Canada, the red leaves occupying a field of white between vertical sections of blue on the edges of the flag.

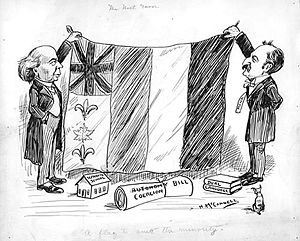

Pearson sought to produce a flag which embodied history and tradition, but he also wanted to excise the Union Jack as a reminder of Canada's heritage and links to the United Kingdom. Hence, the issue was not whether the maple leaf was pre-eminently Canadian, but rather whether the nation should exclude the British-related component from its identity.

Diefenbaker opposition[]

Diefenbaker led the opposition to the Maple Leaf flag, arguing for the retention of the Canadian Red Ensign. Diefenbaker and his lieutenants mounted a filibuster. The seemingly endless debate raged on in Parliament and the press with no side giving quarter. Pearson forced members of Parliament to stay over the summer, but that did not help.

On September 10, 1964, the Prime Minister yielded to the suggestion that the matter be referred to a special flag committee. The key member of the 15-person panel, Liberal Member of Parliament John Matheson said that they "were asked to produce a flag for Canada and in six weeks!"[5]

Special flag committee[]

On September 10, 1964, a committee of 15 Members of Parliament was announced.[5] It was made up of seven Liberals, five Conservatives (PC) and one each from the New Democratic Party (NDP), the Social Credit Party and the Ralliement créditiste.[5]

The Committee members were as follows:[citation needed]

| Member | Party | Electoral district |

|---|---|---|

| Herman Maxwell Batten (chairman)[5] | Liberal | Humber—St. George's, Newfoundland |

| Léo Cadieux | Liberal | Terrebonne, Quebec |

| Grant Deachman | Liberal | Vancouver Quadra, British Columbia |

| Jean-Eudes Dubé | Liberal | Restigouche—Madawaska, New Brunswick |

| Hugh John Flemming | PC | Victoria—Carleton, New Brunswick |

| Margaret Konantz | Liberal | Winnipeg South, Manitoba |

| Raymond Langlois | Ralliement créditiste | Mégantic, Quebec |

| Marcel Lessard | Social Credit | Lac-Saint-Jean, Quebec |

| Joseph Macaluso | Liberal | Hamilton West, Ontario |

| John Matheson | Liberal | Leeds, Ontario |

| Jay Monteith | PC | Perth, Ontario |

| David Vaughan Pugh | PC | Okanagan Boundary, British Columbia |

| Reynold Rapp | PC | Humboldt—Melfort—Tisdale, Saskatchewan |

| Théogène Ricard | PC | Saint-Hyacinthe—Bagot, Quebec |

| Reid Scott | NDP | Danforth, Ontario |

The Conservatives at first saw this event as a victory, for they knew that all previous flag committees had suffered miscarriages. During the next six weeks the committee held 35 lengthy meetings. Thousands of suggestions also poured in from a public engaged in what had become a great Canadian debate about identity and how best to represent it.

3,541 entries were submitted: many contained common elements:

- 2,136 contained maple leaves

- 408 contained Union Jacks

- 389 contained beavers

- 359 contained Fleurs-de-lys

At the last minute, John Matheson slipped a flag designed by historian George Stanley into the mix. The idea came to him while standing in front of the Mackenzie Building of the Royal Military College of Canada, while viewing the college flag flying in the wind. Stanley submitted a March 23, 1964 formal detailed memorandum[6] to Matheson on the history of Canada's emblems, predating Pearson's raising the issue, in which he warned that any new flag "must avoid the use of national or racial symbols that are of a divisive nature" and that it would be "clearly inadvisable" to create a flag that carried either a Union Jack or a Fleur-de-lis. The design put forward had a single red maple leaf on a white plain background, flanked by two red borders, based on the design of the flag of the Royal Military College. The voting was held on October 22, 1964, when the committee’s final contest pitted Pearson’s pennant against Stanley’s. Assuming that the Liberals would vote for the Prime Minister’s design, the Conservatives backed Stanley. They were outmaneuvered by the Liberals who had agreed with others to choose the Stanley Maple Leaf flag. The Liberals voted for the red and white flag, making the selection unanimous (15–0).[7]

House of Commons[]

Debate[]

The committee had made its decision, but not the House of Commons. Diefenbaker would not budge, so the debate continued for six weeks as the Conservatives launched a filibuster. The debate had become so ugly that the Toronto Star called it "The Great Flag Farce."[5]

Closure and vote[]

The debate was prolonged until one of Diefenbaker's own senior members, Léon Balcer, and the Créditiste, Réal Caouette, advised the government to cut off debate by applying closure. Pearson did so, and after some 250 speeches, the final vote adopting the Stanley flag took place at 2:15 on the morning of December 15, 1964, with Balcer and the other francophone Conservatives swinging behind the Liberals. The committee's recommendation was accepted 163 to 78. At 2:00 AM, immediately after the successful vote, Matheson wrote to Stanley: "Your proposed flag has just now been approved by the Commons 163 to 78. Congratulations. I believe it is an excellent flag that will serve Canada well."[8] Diefenbaker, however, called it "a flag by closure, imposed by closure."[9]

On the afternoon of December 15, the Commons also voted in favour of continued use of the Union Flag as a symbol of Canada's allegiance to the Crown and its membership in the Commonwealth of Nations. Senate approval followed on December 17, 1964. The "Royal Union Flag", as it would be officially termed, would be put alongside the new flag on days of Commonwealth significance.

Aftermath[]

Queen Elizabeth II approved the Maple Leaf flag by signing a royal proclamation on January 28, 1965, when both Prime Minister Pearson and Leader of the Opposition Diefenbaker were in London attending the funeral of Sir Winston Churchill.

The flag was inaugurated on February 15, 1965, at an official ceremony held on Parliament Hill in Ottawa in the presence of Governor General Major-General Georges Vanier, the prime minister, the members of the Cabinet, and Canadian parliamentarians. Also throughout Canada, at the United Nations in New York City, and at Canadian legations and on Canadian ships throughout the world, the Canadian Red Ensign was lowered and the Maple Leaf flag was raised. As journalist George Bain wrote of the occasion, the flag "looked bold and clean, and distinctively our own."[10]

Attachment to the old Canadian Red Ensign has persisted among many people, especially veterans.

Provincial flags[]

The Canadian Red Ensign itself can sometimes be seen today in Canada, often in connection to veterans' associations.[11] In addition, the provinces of Manitoba and Ontario adopted their own versions of the Red Ensign as their respective provincial flags in the wake of the national flag debate.

On the other hand, Newfoundland used the Union Flag as its provincial flag from 1952 until 1980; the blue triangles on the new flag adopted in 1980 are meant as a tribute to the Union Flag.[12] British Columbia's flag, which features the Union Flag in its top portion, was introduced in 1960 and is actually based on the shield of the provincial coat of arms, which dates back to 1906.[13] Hence, both Newfoundland's use of the Union Flag and the adoption of British Columbia's flag are unrelated to (and, in fact, pre-date) the great flag debate.

National Flag Day[]

Since 1996, February 15 has been commemorated as National Flag of Canada Day in Canada.

See also[]

- History of Canada

- Australian flag debate

- New Zealand flag debate

- Northern Ireland flags issue

- Flag of Manitoba

- Flag of Ontario

Notes[]

- ^ Levine, Allan. "The Great Flag Debate". Canada's History.

- ^ Fraser, A.B. (1998). The Flags of Canada. Chapter V.

- ^ "<odesi> Dataset: Canadian Gallup Poll, August 1958, #270". odesi1.scholarsportal.info. Retrieved January 21, 2018.

- ^ DePoe, Norman (December 28, 1958). "The Canadian Scene: A Special Report". CBC News Magazine. CBC. Retrieved February 17, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Hunter, Paul (February 14, 2015). "Leader Lester Pearson wanted a flag to represent the new, multicultural Canada. John Diefenbaker was vehemently opposed. The battle was ferocious". The Toronto Star. ISSN 0319-0781. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ "Full text of George Stanley's Flag Memorandum". Archived from the original on March 9, 2014. Retrieved March 19, 2014.

- ^ "How the vote on Canada's flag was 'rigged' | Toronto Star". Thestar.com. February 13, 2015. Retrieved April 18, 2016.

- ^ "John Matheson's postcard to George Stanley, 15 December 1964, 2:00 AM, announcing the House of Commons' approval of Stanley's design for the new Canadian Flag". Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved March 19, 2014.

- ^ Hunter, Paul (February 15, 2015). "Canada's maple leaf flag born amid bitter debate". The Hamilton Spectator. Archived from the original on December 10, 2019. Retrieved December 10, 2019.

- ^ Hillmer, Norman (February 14, 2012). "The Flag: Distinctively Our Own". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved February 17, 2014.

- ^ "Royal Canadian Legion - Colour Party". Royal Canadian Legion. February 25, 2016. Retrieved February 25, 2016.

- ^ "Provincial Flag". Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. Retrieved February 16, 2014.

- ^ "B.C. Quick Facts". Province of British Columbia. Archived from the original on February 16, 2014. Retrieved February 17, 2014.

Bibliography[]

- Albinski, H.S. (1967) "Politics and biculturalism in Canada: The flag debate". Australian Journal of Politics and History, 13. 169–188.

- Band, C.P. & Stovel, E.L. (1925) Our Flag: A Concise Illustrated History. Toronto, ON: Musson Book Co.

- Canada House of Commons. (1964) December 14, 1964 Session. Debates. 11075–11086.

- Pearson's speech of June 15, 1964 can be found in its entirety in the Canada: House of Commons Debates, IV (1964), pp. 4306–4309, 4319–26

- Champion, C.P. "A Very British Coup: Canadianism, Quebec, and Ethnicity in the Flag Debate, 1964–1965." Journal of Canadian Studies 40.3 (2006) 68–99. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa3683/is_200610/ai_n17194033/pg_1

- Champion, C.P. The Strange Demise of British Canada: The Liberals and Canadian Nationalism 1964-68. McGill-Queen's University Press, 2010.

- Diefenbaker, J.G. (1977) The Tumultuous Years 1962–1967 in One Canada: Memoirs of the Right Honourable John G. Diefenbaker. Scarborough, ON: Macmillan. V.3.

- Fraser, A.B. (1991) "A Canadian flag for Canada". Journal of Canadian Studies, v.25. 64–79.

- Fraser, A.B. "The Flags of Canada". http://fraser.cc/FlagsCan/index.html

- Granatstein, J.L. (1986) Canada: 1957–1967: The Years of Uncertainty and Innovation. Toronto, ON: McClelland and Stewart.

- Kelly, K. (1964) "Closure Day in Parliament: Flag debate may die in Commons, revive in Senate". Chronicle Herald Dec. 15, 1964. 1, 6.

- Matheson, J.R. "Lester Pearson and the flag, 1960–1964" in Canada’s Flag: A Search for a Country https://web.archive.org/web/20050725003644/http://collections.ic.gc.ca/flag/html/contents.htm

- Stanley, G.F.G. (1965) The Story of Canada's Flag: A Historical Sketch. Toronto: Ryerson Press.

- Flag Debate in The Canadian Encyclopedia

- The Flags of Canada, by Alistair B. Fraser.

- Canada, flag proposals

- Dr. George F.G. Stanley's Flag Memorandum, 23 March 1964

External links[]

- Canadian culture

- Flags of Canada

- Political history of Canada

- 1964 in Canada

- History of Canada (1960–1981)

- Flag controversies

- John Diefenbaker

- Political controversies in Canada

- 1963 in Canada

- Political debates

- 1963 in Canadian politics

- 1964 in Canadian politics