Great Disappointment

| Part of a series on |

| Adventism |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Seventh-day Adventist Church |

|---|

|

| Adventism |

The Great Disappointment in the Millerite movement was the reaction that followed Baptist preacher William Miller's proclamations that Jesus Christ would return to the Earth by 1844, what he called the Advent. His study of the Daniel 8 prophecy during the Second Great Awakening led him to the conclusion that Daniel's "cleansing of the sanctuary" was cleansing of the world from sin when Christ would come, and he and many others prepared. However, October 22, 1844 passing with nothing significant happening, causing great disappointment among his following.[1][2][3][4]

These events paved the way for a few of the former Millerite Adventists to eventually form the Seventh-day Adventist Church. They contend that what happened on October 22 was the start of Jesus' final work of atonement, the cleansing of the heavenly sanctuary, leading up to the Second Coming.[1][2][3][4]

Miller believed the Second Coming of Christ was imminent[]

Between 1831 and 1844, on the basis of his study of the Bible, and particularly the prophecy of Daniel 8:14—"Unto two thousand and three hundred days; then shall the sanctuary be cleansed"—William Miller, a rural New York farmer and Baptist lay preacher, predicted and preached the return of Jesus Christ to the earth. Miller's teachings form the theological foundation of Seventh-day Adventism. Four topics were especially important: 1. Miller's use of the Bible; 2. his eschatology; 3. his perspective on the first and second angel's messages of Revelation 14; and 4. the seventh-month movement that ended with the "Great Disappointment".[5]

- 1. Miller's use of the Bible

Miller's approach was thorough and methodical, intensive and extensive. Central to his general principles Biblical interpretation was that "all scripture is necessary" and that no part should be bypassed. To understand a doctrine, Miller said one needed to "bring all scriptures together on the subject you wish to know; then let every word have its proper influence, and if you can form your theory without a contradiction you cannot be in error." He held that the Bible should be its own expositor. By comparing scripture with scripture a person could unlock the meaning of the Bible. In that way the Bible became a person's authority, whereas if a creed of other individuals or their writings served as the basis of authority, then that external authority became central rather than the teaching of the Bible itself."[6] Miller's guidelines concerning the interpretation Bible prophecy was built upon the same concepts set forth in his general rules. The Bible, so far as Miller and his followers were concerned, was the supreme authority in all matters of faith and doctrine.[7]

- 2. Second Advent

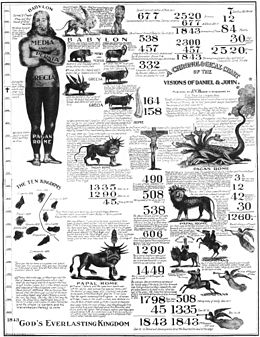

Millerism was essentially a one-doctrine movement--the visual, literal, premillennial return of Jesus in the clouds of heaven. Miller was not alone in his interest in prophecies. The unprecedented upheaval of the French Revolution in the 1790s was one of several factors that turned the eyes of Bible students around the world to the prophecies of Daniel and Revelation. Coming to the Bible with a historicist scheme of interpretation and the concept that a prophetic day equals a real time year, Bible scholars began to study the time prophecies. Of special interest to many was the 1260 prophetic day time prophecy of Daniel 7:25. Many concluded that the end of the 1260-day prophecy initiated "time of the end". They dated that to the 1790s. Having to their satisfaction solved the 1260 days, it was only natural that they would turn their attention to unlocking the riddle of the 2300 days of Daniel 8:14.[8]

Miller turned to the text Daniel 8:14, "Unto two thousand and three hundred days; then shall the sanctuary be cleansed." There were three things that Miller determined about this text:[9]

- That the 2,300 symbolic days represented 2,300 real years as evidence in Ezekiel 4:6 and Numbers 14:34.

- That the sanctuary represents the earth or church. And,

- by referring to 2 Peter 3:7, that the 2,300 years ended with the burning of the earth at the Second Advent.

The beginning of the prophecy is not given, however Miller tied the vision to the 70-week prophecy in chapter 9 where a beginning is given. He concluded that the 70-weeks (or 70-7s or 490 days/years) were the first 490 years of the 2300 years. The 490 years were to begin with the command to rebuild and restore Jerusalem. The bible records 4 decrees concerning Jerusalem after the Babylonian captivity:

- 536 BC: Decree by Cyrus to rebuild temple.[10]

- 519 BC: Decree by Darius I to finish temple.[11]

- 457 BC: Decree by Artaxerxes I of Persia.[12]

- 444 BC: Decree by Artaxerxes to Nehemiah to finish wall at Jerusalem.[13]

The decree by Artaxerxes empowered Ezra to ordain laws, set up magistrates and judges; i.e. to the restored Jewish state. And gave him unlimited funds to rebuild whatever he wanted at Jerusalem.[14]

Miller concluded that 457 BC was the beginning of the 2,300 day/year prophecy which meant that it would end about 1843-1844 (-457 BC + 2300 years = 1843 AD). And so, too, the Second Advent would happen about that time.[9]

- 3. Revelation 14's 1st & 2nd Angels' messages

The first angel proclaimed both the "everlasting gospel" and "the hour of [God's] judgment is come." While Miller believed that the first angel's message represented "the sending out of Missionaries and Bibles into every part of the world, which began about 1798," his followers came to see "the hour of his judgment" as the judgement day when Jesus would return. Throughout the 1830s increasing numbers of Protestant churches opened their doors to his preaching, not so much because of his "peculiar" preaching but because of his ability to bring converts to fill their churches. But a message that seemed harmless enough at first threatened to disrupt the churches by 1843. Millerism was not a separate movement at that time and the majority of believers remained members of the various churches. As 1843 approached, and Millerites became more assertive on the truth of the Bible over creeds, they increasingly found themselves forbidden to speak of their beliefs in their own congregations. When they persisted they were disfellowshipped. Also, large numbers of congregations expelled pastors who supported Miller's teachings, and refused to listen to Second Advent preaching. Millerite preacher Charles Fitch tied this to the second angels message of "Babylon is fallen .. come out of her my people." Fitch now included those Protestant churches which rejected the Millerite teachings of the imminent second Advent with the Rome Catholic Church as being "Babylon." He called for his hearers to "come out of Babylon or perish." Fitch provided his fellow Adventists a theological rationale for separating from their churches. It is difficult to overestimate the impact on the Adventist movement by Fitch's call. By 1844 some estimate that more than 50,000 Millerite believers had abandoned their churches.[15]

- 4. 7th-month movement

Miller originally resisted being too specific about the exact time of Christ's return. But he did narrow the time period to sometime in the Jewish year 5604, stating: "My principles in brief, are, that Jesus Christ will come again to this earth, cleanse, purify, and take possession of the same, with all the saints, sometime between March 21, 1843 and March 21, 1844."[16] Although this time passed, the spring disappointment did not greatly affect the movement. After further discussion and study, he briefly adopted a new date—April 18, 1844—one based on the Karaite Jewish calendar (as opposed to the Rabbinic calendar).[17] Like the previous date, April 18 passed without Christ's return. In the Advent Herald of April 24, Joshua Himes wrote that all the "expected and published time" had passed and admitted that they had been "mistaken in the precise time of the termination of the prophetic period". Josiah Litch surmised that the Adventists were probably "only in error relative to the event which marked its close". Miller published a letter "To Second Advent Believers," writing, "I confess my error, and acknowledge my disappointment; yet I still believe that the day of the Lord is near, even at the door."[18]

Then, in Mid-August, S.S. Snow argued that the tenth day of the 7th month, the Day of Atonement, which fell on October 22 in 1844, would be the day that Christ would come. At first, Miller and Himes were reluctant to accept this date, however by October 6, they both came out in support of the 22nd of October. With the expectation of the Second Advent at an all-time high, October 22, 1844, was the climax of Millerism.[19]

The October 22, 1844, Great Disappointment[]

October 22 passed without incident, resulting in feelings of disappointment among many Millerites.[20] and encouraging the scoffers and fearful. The Millerites were in total disarray. Whereas once the movement knew exactly where it was going, it was now in a state of uncertainty and in a state of crisis.[19]

Henry Emmons, a Millerite, later wrote,

I waited all Tuesday [October 22] and dear Jesus did not come;– I waited all the forenoon of Wednesday, and was well in body as I ever was, but after 12 o'clock I began to feel faint, and before dark I needed someone to help me up to my chamber, as my natural strength was leaving me very fast, and I lay prostrate for 2 days without any pain– sick with disappointment.[21]

Repercussions[]

The Millerites had to deal with their own shattered expectations, as well as considerable criticism and even violence from the public. Many followers had given up their possessions in expectation of Christ's return. On November 18, 1844, Miller wrote to Himes about his experiences:

Some are tauntingly enquiring, 'Have you not gone up?' Even little children in the streets are shouting continually to passersby, 'Have you a ticket to go up?' The public prints, of the most fashionable and popular kind ... are caricaturing in the most shameful manner of the 'white robes of the saints,' Revelation 6:11, the 'going up,' and the great day of 'burning.' Even the pulpits are desecrated by the repetition of scandalous and false reports concerning the 'ascension robes', and priests are using their powers and pens to fill the catalogue of scoffing in the most scandalous periodicals of the day.[22]

There were also the instances of violence: a Millerite church was burned in Ithaca, New York, and two were vandalized in Dansville and Scottsville. In Loraine, Illinois, a mob attacked the Millerite congregation with clubs and knives, while a group in Toronto was tarred and feathered. Shots were fired at another Canadian group meeting in a private house.[23]

Theological development following the Great Disappointment[]

Both Millerite leaders and followers were left in utter confusion following the wake of the October 22 disappointment. The majority of Millerites left the faith and even Christianity altogether, while some rejoined their previous denominations.[24][25]

By mid-1845, doctrinal lines among the various Millerite groups began to solidify, and the groups emphasized their differences, in a process George R. Knight terms "sect building". During this time, there were three main Millerite groups besides those who had simply given up their beliefs.[26]

The first major division of the Millerite groups who retained a belief in Christ's Second Advent were those who focused on the "shut-door" belief. Popularized by Joseph Turner, this belief was based on a key Millerite passage: Matthew 25:1–13—the parable of the ten virgins.[27] The shut door mentioned in Matthew 25:11–12 was interpreted as the close of probation. As Knight explains, "After the door was shut, there would be no additional salvation. The wise virgins (true believers) would be in the kingdom, while the foolish virgins and all others would be on the outside."[28]

The widespread acceptance of the shut-door belief lost ground as doubts were raised about the significance of the October 22, 1844 date—if nothing happened on that date, then there could be no shut door. The opposition to these shut-door beliefs was led by Himes and make up the second post-1844 group. This faction soon gained the upper hand, even converting Miller to their point of view. Their influence was enhanced by the staging of the Albany Conference. The Advent Christian Church has its roots in this post-Great Disappointment group.

Among the shut door groups were the "Spiritualizers" who offered a spiritualized interpretation concluding that the Millerites had been correct on both the time and event, but Jesus' Advent had been spiritual, coming to the hearts of the believers rather than visible in the heavens.[24] Some of these Spiritualizers theorized that the world had entered the seventh millennium—the "Great Sabbath", and that therefore, the saved should not work. Others behaved like children, basing their belief on Jesus' words in Mark 10:15: "Truly, I say to you, whoever does not receive the kingdom of God like a child shall not enter it." Millerite O. J. D. Pickands used Revelation 14:14–16 to teach that Christ was now sitting on a white cloud and must be prayed down.[29] A substantial number joined the Shakers.[30]

By far the smallest group of Millerites consisted of a few Bible students scattered across New England who did not personally know one another before about 1847. They accepted the fulfillment of the 2300 days prophecy of Daniel 8:14, but disagreed with the other Millerites on the event that took place.[31] Rather than Christ having returned invisibly they concluded that the event that took place on October 22, 1844, was quite different.[29]

The theology of this third group appears to have had its beginnings as early as October 23, 1844—the day after the Great Disappointment. On that day, during a prayer session with a group of Advent believers, Hiram Edson became convinced that "light would be given" and their "disappointment explained." Later that day, Edson was struck by the idea that the sanctuary to be cleansed was not the earth by fire, but rather something related to the heavenly sanctuary.[29] His experience led him into an protracted and extensive study on the topic with O. R. L. Crosier and F. B. Hahn. They eventually came to the conclusion that Miller's assumption that the sanctuary represented the earth was in error. Rather, "The sanctuary to be cleansed in Daniel 8:14 was not the earth or the church, but the sanctuary in heaven." Therefore, October 22 marked not the Second Coming of Christ, but rather a heavenly event. Their interpretation published in early 1845 in the Day Dawn, became known as the Investigative Judgment.[32][31] It was from this group that future leaders of Seventh-day Adventism came.[31]

| Reaction of Millerites to the Great Disappointment[33] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| What Happened on October 22, 1844? | Attitude toward Prophecy | Reaction | Numbers of Millerites | Current groups |

| No Second Advent | 1844 date invalid so prophecy invalid |

Abandoned their beliefs | Tens of thousands | Majority left Christianity Minority rejoined former churches |

| No Second Advent | 1844 date invalid but prophecy valid |

Jesus coming soon Some set other dates |

Many hundreds | Advent Christian Church, Jehovah's Witnesses |

| Second Advent occurred – Spiritualized | 1844 date valid and prophecy valid |

Short lived “holy flesh” movement | Hundreds | Some joined Shakers |

| Prophecy not about Second Advent rather, beginning of Pre-Advent judgement |

1844 date valid and prophecy valid |

Adjusted to new theology with Second Advent still in future |

A few dozen | Seventh-day Adventist Church |

Protestants and Evangelicals abandon Historicism[]

Following the very public humiliation of the October 22, 1844, Great Disappointment there was widespread abandonment of historicism in eschatology among American Protestant and Evangelical churches in favor of the new Dispensationalism that is composed of elements of Futurism, which focuses on the tribulation period of the unrighteous left behind to be punished by suffering through the chronology of wars and famines laid out in Revelation, and mutually exclusive Preterism, which eschews the idea of a millennium entirely.[34] The Seventh-day Adventists and the Jehovah's Witnesses are among the few larger groups that still adhere to a historicist interpretation of Bible prophecy.[35]

The Bahá'í Faith[]

The Bahá'ís have been teaching about connections between the start of their religion and the fulfillment of the Daniel 8:14 prophecy since its earliest teachers began to teach in the West in the 1890s.[36] Their interpretation of this prophecy closely matches the interpretation of William Miller. They believe that Miller's interpretation of signs and dates of the coming of Jesus were, for the most part, correct[37] and that a forerunner of their own religion, the Báb, who declared that he was the "Promised One" on May 23, 1844, and began openly teaching in Persia in October 1844, was fulfillment of biblical prophecies of the coming of Christ.[38][39] Several recent Bahá'í books and pamphlets make mention of the Millerites, the prophecies used by Miller and the Great Disappointment, most notably Bahá'í follower William Sears' Thief in the Night.[40][41][42]

The year 1844 was also the Year AH 1260. Sears tied Daniel's prophecies in with the Book of Revelation in the New Testament in support of Bahá'í teaching, interpreting the year 1260 as the "times, time and half a time" of Daniel 7:25 (3 and 1/2 years = 42 months = 1260 days). Using the same day-year principle as did William Miller, Sears decoded these texts into the year AH 1260, or 1844 in his book.[43]

Bahá'ís believe that if William Miller had known the year 1844 was also the year AH1260, then he may have considered that there were other signs for which to look. Bahá'í teachings on the implications of their interpretations of chapters 11 and 12 of the Book of Revelation, together with the predictions of Daniel as used by William Miller, were explained by 'Abdu'l-Bahá, the son of the founder of the Bahá'í Faith, to Laura Clifford Barney and published in 1908 in Some Answered Questions.[44]

Naturalistic explanations by Skeptics[]

The Great Disappointment is viewed by scholars for whom there is no God as an example of cognitive dissonance[45] and True-believer syndrome. The theory was proposed by Leon Festinger to describe the formation of new beliefs and increased proselytizing in order to reduce the tension, or dissonance, that results from failed prophecies.[46] According to the theory, believers experienced tension following the failure of Jesus' reappearance in 1844, which led to a variety of new explanations. The various solutions form a part of the teachings of the different groups that outlived the disappointment.

In popular culture[]

Hardcore punk band AFI wrote a song about the event, also titled "The Great Disappointment". It appears on the album Sing the Sorrow.

The Great Disappointment was depicted in a sequence of scenes that opens the first episode of the third and final season of the TV series The Leftovers.[47]

See also[]

- Adventism

- Adventist

- Burned-over district

- Christianity in the 19th century

- Escalation of commitment

- List of Christian denominations § Millerites and comparable groups

- List of religions and religious denominations § Adventist and related churches

- Millennialism

- Predictions and claims for the Second Coming of Christ

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Seventh-day Adventist Church emerged from religious fervor of 19th Century". 4 October 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Apocalypticism Explained - Apocalypse! FRONTLINE - PBS". Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Great Disappointment and the Birth of Adventism". Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Adventist Review Online - Great Disappointment Remembered 170 Years On". Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- ^ Knight 2000, pp. 38.

- ^ Miller, William (November 17, 1842). "Midnight Cry". p. 4. Cite magazine requires

|magazine=(help) - ^ Knight 2000, pp. 39–42.

- ^ Knight 2000, pp. 42–44.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Knight 2000, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Ezra 1:1–4

- ^ Ezra 6:1–12

- ^ Ezra 7

- ^ Nehemiah 2

- ^ Smith 1898, pp. 208–209.

- ^ Knight 2000, pp. 47–50.

- ^ Bliss 1853, p. 256, A letter from Miller to Joshua V. Himes, February 4, 1844

- ^ Knight 1993, pp. 163–164.

- ^ Bliss 1853, p. 256.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Knight 2000, pp. 50–54.

- ^ "The Great Disappointment | Grace Communion International". www.gci.org. Archived from the original on 2016-03-23. Retrieved 2015-11-20.

- ^ Knight 1993, pp. 217–218.

- ^ White, James (1875). Sketches of the Christian Life and Public Labors of William Miller: Gathered From His Memoir by the Late Sylvester Bliss, and From Other Sources. Battle Creek: Steam Press of the Seventh-day Adventist Publishing Association. p. 310.

- ^ Knight 1993, pp. 222–223.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Knight 2000, p. 55.

- ^ Knight 1993, p. 232.

- ^ Knight 1993, p. 232.

- ^ Dick, Everett N. (1994). William Miller and the Advent Crisis. Berrien Springs, Michigan: Andrews University Press. p. 25.

- ^ Knight 1993, p. 236.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Knight 1993, p. 305.

- ^ Cross, Whitney R. (1950). The Burned-over District: A Social and Intellectual History of Enthusiastic Religion in Western New York. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. p. 310.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Knight 2000, pp. 55–58.

- ^ Knight 1993, p. 305-306.

- ^ Derived from Knight 2000

- ^ Barnard, John Richard (August 2012). The Millerite Movement and American Millenial Culture, 1830-1845 (Thesis). Southern Illinois University: Carbondale. p. 63.

Another lasting legacy of the Millerite movement is the widespread abandonment of the method of prophetic interpretation used by Miller: historicism. The very public humiliation of October 22, 1844 greatly limited the use of historicism. Instead, new eschatological methods came to dominate American theology regarding the end times, most notably futurism, which focuses on the tribulation period of the unrighteous left behind to be punished by suffering through the chronology of wars and famines laid out in Revelation, and preterism, which eschews the idea of a millennium entirely.

- ^ Barnard 2012, p. 63.

- ^ Stockman, Robert H. (1985). The Baha'i Faith in America-Origins 1892-1900 (1st ed.). Wilmette, Illinois: Baha'i Publishing Trust. pp. 75–76. ISBN 0-87743-199-X.

- ^ Momen, Moojan (1992). "Fundamentalism and Liberalism: towards an understanding of the dichotomy". Bahá'í Studies Review. 2 (1).

- ^ Cameron, G.; Momen, W. (1996). A Basic Bahá'í Chronology. Oxford, UK: George Ronald. pp. 15–20, 125. ISBN 0-85398-404-2.

- ^ Shoghi Effendi Rabbani. God Passes By. p. 9.

- ^ Sears 1961.

- ^ Bowers, Kenneth E. (2004). God Speaks Again: An Introduction to the Bahá'í Faith. Baha'i Publishing Trust. p. 12. ISBN 1-931847-12-6.

- ^ Motlagh, Hushidar Hugh (1992). I Shall Come Again (The Great Disappointment ed.). Mt. Pleasant, MI: Global Perspective. pp. 205–213. ISBN 0-937661-01-5.

- ^ Sears, William (1961). Thief in the Night (1st ed.). Oxford, England: George Ronald. p. 26. ISBN 0-85398-008-X.

- ^ 'Abdu'l-Baha (2014). Some Answered Questions (2014 ed.). Haifa, Israel: Baha'i World Centre. pp. 46–81. ISBN 978-0-87743-374-3.

- ^ O'Leary, Stephen (2000). "When Prophecy Fails and When it Succeeds: Apocalyptic Prediction and Re-Entry into Ordinary Time". In Albert I. Baumgarten (ed.). Apocalyptic Time. Brill Publishers. p. 356. ISBN 90-04-11879-9.

Examining Millerite accounts of the Great Disappointment, it is clear that Festinger's theory of cognitive dissonance is relevant to the experience of this apocalyptic movement.

- ^ Richardson.

- ^ "'The Leftovers' Final Season Begins With The Surprising 'Book Of Kevin'". 16 April 2017. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

Bibliography[]

- Knight, George R. (1993). Millennial Fever and the End of the World. Boise, Idaho: Pacific Press. ISBN 9780816311781.

- Knight, George (2000). A Search for Identity. Review and Herald Pub.

- Rowe, David L. (2008). God's Strange Work: William Miller and the End of the World. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-0380-1.

External links[]

- 1844 in Christianity

- 1844 in the United States

- 19th-century Protestantism

- Adventism

- Christian eschatology

- Christian terminology

- History of Christianity in the United States

- History of the Seventh-day Adventist Church

- Prophecy