Millennialism

| Part of a series on |

| Eschatology |

|---|

Millennialism (from millennium, Latin for "a thousand years") or chiliasm (from the Greek equivalent) is a belief advanced by some religious denominations that a Golden Age or Paradise will occur on Earth prior to the final judgment and future eternal state of the "World to Come".

Christianity and Judaism have both produced messianic movements which featured millennialist teachings—such as the notion that an earthly kingdom of God was at hand. These millenarian movements often led to considerable social unrest.[1]

Similarities to millennialism appear in Zoroastrianism, which identified successive thousand-year periods, each of which will end in a cataclysm of heresy and destruction, until the final destruction of evil and of the spirit of evil by a triumphant king of peace at the end of the final millennial age. "Then Saoshyant makes the creatures again pure, and the resurrection and future existence occur" (Zand-i Vohuman Yasht 3:62).

Scholars have also linked various other social and political movements, both religious and secular, to millennialist metaphors.

Baha'i Faith[]

Bahá'u'lláh mentioned in the Kitáb-i-Íqán that God will renew the "City of God" about every thousand years,[2] and specifically mentioned that a new Manifestation of God would not appear within 1,000 years (1893–2893) of Bahá'u'lláh's message, but that the authority of Bahá'u'lláh's message could last up to 500,000 years.[3][4]

Christianity[]

Christian millennialist thinking is based upon the Book of Revelation, specifically Revelation 20, which describes the vision of an angel who descended from heaven with a large chain and a key to a bottomless pit, and captured Satan, imprisoning him for a thousand years:

He seized the dragon, that ancient serpent, who is the Devil and Satan, and bound him for a thousand years and threw him into the pit and locked and sealed it over him, so that he would deceive the nations no more, until the thousand years were ended. After that, he must be let out for a little while.

The Book of Revelation then describes a series of judges who are seated on thrones, as well as John's vision of the souls of those who were beheaded for their testimony in favor of Jesus and their rejection of the mark of the beast. These souls:

came to life and reigned with Christ a thousand years. (The rest of the dead did not come to life until the thousand years were ended.) This is the first resurrection. Blessed and holy are those who share in the first resurrection. Over these the second death has no power, but they will be priests of God and of Christ, and they will reign with him a thousand years

Early church[]

| Christian eschatology |

|---|

| Christianity portal |

During the first centuries after Christ, various forms of chiliasm (millennialism) were to be found in the Church, both East and West.[5] It was a decidedly majority view at that time, as admitted by Eusebius, himself an opponent of the doctrine:

The same writer (that is to say, Papias of Hierapolis) gives also other accounts which he says came to him through unwritten tradition, certain strange parables and teachings of the Saviour, and some other more mythical things. To these belong his statement that there will be a period of some thousand years after the resurrection of the dead, and that the kingdom of Christ will be set up in material form on this very earth. I suppose he got these ideas through a misunderstanding of the apostolic accounts, not perceiving that the things said by them were spoken mystically in figures. For he appears to have been of very limited understanding, as one can see from his discourses. But it was due to him that so many of the Church Fathers after him adopted a like opinion, urging in their own support the antiquity of the man; as for instance Irenaeus and any one else that may have proclaimed similar views.

— Eusebius, The History of the Church, Book 3:39:11-13[6]

Nevertheless, strong opposition later developed from some quarters, most notably from Augustine of Hippo. The Church never took a formal position on the issue at any of the ecumenical councils, and thus both pro and con positions remained consistent with orthodoxy. The addition to the Nicene Creed was intended to refute the perceived Sabellianism of Marcellus of Ancyra and others, a doctrine which includes an end to Christ's reign and which is explicitly singled out for condemnation by the council [Canon #1].[7][8] The Catholic Encyclopedia notes that the 2nd century proponents of various Gnostic beliefs (themselves considered heresies) also rejected millenarianism.[9]

Millennialism was taught by various earlier writers such as Justin Martyr,[10] Irenaeus, Tertullian, Commodian, Lactantius, Methodius, and Apollinaris of Laodicea in a form now called premillennialism.[11] According to religious scholar Rev. Dr. Francis Nigel Lee,[12] "Justin's 'Occasional Chiliasm' sui generis which was strongly anti-pretribulationistic was followed possibly by Pothinus in A.D. 175 and more probably (around 185) by Irenaeus". Justin Martyr, discussing his own premillennial beliefs in his Dialogue with Trypho the Jew, Chapter 110, observed that they were not necessary to Christians:

I admitted to you formerly, that I and many others are of this opinion, and [believe] that such will take place, as you assuredly are aware; but, on the other hand, I signified to you that many who belong to the pure and pious faith, and are true Christians, think otherwise.[13]

Melito of Sardis is frequently listed as a second century proponent of premillennialism.[14] The support usually given for the supposition is that "Jerome [Comm. on Ezek. 36] and Gennadius [De Dogm. Eccl., Ch. 52] both affirm that he was a decided millenarian."[15]

In the early third century, Hippolytus of Rome wrote:

And 6,000 years must needs be accomplished, in order that the Sabbath may come, the rest, the holy day "on which God rested from all His works." For the Sabbath is the type and emblem of the future kingdom of the saints, when they "shall reign with Christ," when He comes from heaven, as John says in his Apocalypse: for "a day with the Lord is as a thousand years." Since, then, in six days God made all things, it follows that 6, 000 years must be fulfilled. (Hippolytus. On the HexaËmeron, Or Six Days' Work. From Fragments from Commentaries on Various Books of Scripture).

Around 220, there were some similar influences on Tertullian, although only with very important and extremely optimistic (if not perhaps even postmillennial) modifications and implications. On the other hand, "Christian Chiliastic" ideas were indeed advocated in 240 by Commodian; in 250 by the Egyptian Bishop Nepos in his Refutation of Allegorists; in 260 by the almost unknown ; and in 310 by Lactantius. Into the late fourth century, Bishop Ambrose of Milan had millennial leanings (Ambrose of Milan. Book II. On the Belief in the Resurrection, verse 108). Lactantius is the last great literary defender of chiliasm in the early Christian church. Jerome and Augustine vigorously opposed chiliasm by teaching the symbolic interpretation of the Revelation of St. John, especially chapter 20.[16]

In a letter to Queen Gerberga of France around 950, Adso of Montier-en-Der established the idea of a "last World Emperor" who would conquer non-Christians before the arrival of the Antichrist.[17]

Reformation and beyond[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2020) |

Christian views on the future order of events diversified after the Protestant reformation (c.1517). In particular, new emphasis was placed on the passages in the Book of Revelation which seemed to say that as Christ would return to judge the living and the dead, Satan would be locked away for 1000 years, but then released on the world to instigate a final battle against God and his Saints (Revelation 20:1–6). Previous Catholic and Orthodox theologians had no clear or consensus view on what this actually meant (only the concept of the end of the world coming unexpectedly, "like a thief in a night", and the concept of "the antichrist" were almost universally held). Millennialist theories try to explain what this "1000 years of Satan bound in chains" would be like.

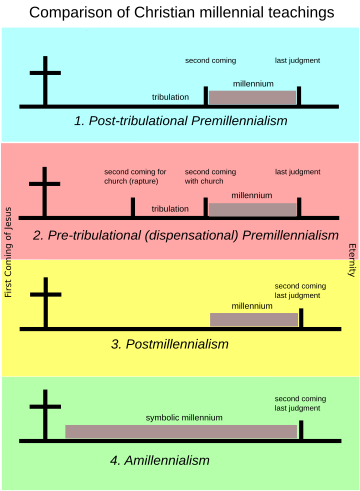

Various types of millennialism exist with regard to Christian eschatology, especially within Protestantism, such as Premillennialism, Postmillennialism, and Amillennialism. The first two refer to different views of the relationship between the "millennial Kingdom" and Christ's second coming.

Premillennialism sees Christ's second advent as preceding the millennium, thereby separating the second coming from the final judgment. In this view, "Christ's reign" will be physically on the earth.

Postmillennialism sees Christ's second coming as subsequent to the millennium and concurrent with the final judgment. In this view "Christ's reign" (during the millennium) will be spiritual in and through the church.

Amillennialism basically denies a future literal 1000 year kingdom and sees the church age metaphorically described in Rev. 20:1–6 in which "Christ's reign" is current in and through the church.

The Catholic Church strongly condemns millennialism as the following shows:

The Antichrist's deception already begins to take shape in the world every time the claim is made to realize within history that messianic hope which can only be realized beyond history through the eschatological judgment. The Church has rejected even modified forms of this falsification of the kingdom to come under the name of millenarianism, especially the "intrinsically perverse" political form of a secular messianism.

— Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1995[18]

19th and 20th centuries[]

Bible Student movement[]

The Bible Student movement is a millennialist movement based on views expressed in "The Divine Plan of the Ages," in 1886, in Volume One of the Studies in the Scriptures series, by Pastor Charles Taze Russell. (This series is still being published, since 1927, by the Dawn Bible Students Association.) Bible Students believe that there will be a universal opportunity for every person, past and present, not previously recipients of a heavenly calling, to gain everlasting life on Earth during the Millennium.[19]

Jehovah's Witnesses[]

Jehovah's Witnesses believe that Christ will rule from heaven for 1,000 years as king over the earth, assisted by the 144,000 ascended humans.[20]

The Church of Almighty God[]

Also known as Eastern Lightning, The Church of Almighty God mentions in its teachings the Age of Millennial Kingdom, which will follow the catastrophes prophesied in the Book of Revelation.[21]

Judaism[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (November 2018) |

Millennialist thinking first emerged in Jewish apocryphal literature of the tumultuous Second Temple period,[22] producing writings such as the Psalm 46, the Book of Enoch, the Book of Jubilees, Esdras, Book of Daniel, and the additions to Daniel.[citation needed]

Passages within these texts, including 1 Enoch 6-36, 91-104, 2 Enoch 33:1, and Jubilees 23:27, refer to the establishment of a "millennial kingdom" by a messianic figure, occasionally suggesting that this kingdom would endure for a thousand years. However, the actual number of years given for the duration of the kingdom varied. In 4 Ezra 7:28-9, for example, the kingdom lasts only 400 years.

This notion of the millennium no doubt helped some Jews to cope with the socio-political conflicts that they faced.[citation needed] This concept of the millennium served to reverse the previous period of evil and suffering,[citation needed] rewarding the virtuous for their courage while punishing evil-doers, with a clear separation of those who are good from those who are evil. The vision of a thousand-year period of bliss for the faithful, to be enjoyed here in the physical world as "heaven on earth", exerted an irresistible power over the imagination of Jews in the inter-testamental period as well as on early Christians.[citation needed] Millennialism, which had already existed in Jewish thought, received a new interpretation and fresh impetus with the development of Christianity.[citation needed]

Gerschom Scholem profiles medieval and early modern Jewish millennialist teachings in his book Sabbatai Sevi, the mystical messiah, which focuses on the 17th-century movement centered on the self-proclaimed messiahship (1648) of Sabbatai Zevi[23] (1626–1676).

Theosophy[]

The Theosophist Alice Bailey taught that Christ (in her books she refers to the powerful spiritual being best known by Theosophists as Maitreya as The Christ or The World Teacher, not as Maitreya)[clarification needed] would return “sometime after AD 2025”, and that this would be the New Age equivalent of the Christian concept of the Second Coming of Christ.[24][25]

Social movements[]

Millennial social movements, a specific form of millenarianism, have as their basis some concept of a cycle of one-thousand years. Sometimes[quantify] the two terms[which?] are used[by whom?] as synonyms, but purists regard this as not entirely accurate.[citation needed] Millennial social movements need not have a religious foundation, but they must[need quotation to verify] have a vision of an apocalypse that can be utopian or dystopian. Those associated with millennial social movements are "prone to be violent",[citation needed] with certain types of millennialism connected to violence.[26][27] In progressive millennialism, the "transformation of the social order is gradual and humans play a role in fostering that transformation".[28] Catastrophic millennialism "deems the current social order as irrevocably corrupt, and total destruction of this order is necessary as the precursor to the building of a new, godly order".[29] However the link between millennialism and violence may be problematic, as new religious movements may stray from the catastrophic view as time progresses.[30][need quotation to verify]

Nazism[]

The most controversial interpretation of the Three Ages philosophy and of millennialism in general involves Adolf Hitler's "Third Reich" ("Drittes Reich"), which in his vision would last for a thousand years to come ("Tausendjähriges Reich") but ultimately lasted for only 12 years (1933–1945).

The German thinker Arthur Moeller van den Bruck coined the phrase "Third Reich" and in 1923 published a book titled Das Dritte Reich. Looking back at German history, he distinguished two separate periods, and identified them with the ages of the 12th-century Italian theologian Joachim of Fiore:

- the Holy Roman Empire (beginning with Charlemagne in AD 800): the "First Reich", The Age of the Father and

- the German Empire, under the Hohenzollern dynasty (1871–1918): the "Second Reich", The Age of the Son.

After the interval of the Weimar Republic (1918 onwards), during which constitutionalism, parliamentarianism and even pacifism dominated, these were then to be followed by:

- the "Third Reich", The Age of the Holy Spirit.

Although van den Bruck was unimpressed by Hitler when he met him in 1922 and did not join the Nazi Party, nevertheless the Nazis adopted the term "Third Reich" to label the totalitarian state they wanted to set up when they gained power, which they succeeded in doing in 1933. Later, however, the Nazi authorities banned the informal use of "Third Reich" throughout the German press in the summer of 1939, instructing it to use more official terms such as "German Reich", "Greater German Reich", and "National Socialist Germany" exclusively.[31]

During the early part of the Third Reich many Germans also referred to Hitler as being the German Messiah, especially when he conducted the Nuremberg Rallies,[citation needed] which came to be held annually (1933-1938) at a date somewhat before the Autumn Equinox in Nuremberg, Germany.

In a speech held on 27 November 1937, Hitler commented on his plans to have major parts of Berlin torn down and rebuilt:

- [...] einem tausendjährigen Volk mit tausendjähriger geschichtlicher und kultureller Vergangenheit für die vor ihm liegende unabsehbare Zukunft eine ebenbürtige tausendjährige Stadt zu bauen [...].

- [...] to build a millennial city adequate [in splendour] to a thousand-year-old people with a thousand-year-old historical and cultural past, for its never-ending [glorious] future [...]

After Adolf Hitler's unsuccessful attempt to implement a thousand-year-reign, the Vatican issued an official statement that millennial claims could not be safely taught and that the related scriptures in Revelation (also called the Apocalypse) should be understood spiritually. Catholic author Bernard LeFrois wrote:

- Millenium [sic]: [...] Since the Holy Office decreed (July 21, 1944) that it cannot be safely taught that Christ at His Second Coming will reign visibly with only some of His saints (risen from the dead) for a period of time before the final and universal judgment, a spiritual millenium is to be seen in Apoc. 20:4–6. St. John gives a recapitulation of the activity of Satan, and the spiritual reign of the saints with Christ in heaven and in His Church on earth.[32]

Utopianism[]

The early Christian concepts of millennialism had ramifications far beyond strictly religious concerns during the centuries to come, as various theorists blended and enhanced them with ideas of utopia.

In the wake of early millennial thinking, the Three Ages philosophy developed. The Italian monk and theologian Joachim of Fiore (died 1202) saw all of human history as a succession of three ages:

- the Age of the Father (the Old Testament)

- the Age of the Son (the New Testament)

- the Age of the Holy Spirit (the age begun when Christ ascended into heaven, leaving the Paraclete, the third person of the Holy Trinity, to guide the faithful)

It was believed[by whom?] that the Age of the Holy Spirit would begin at around 1260, and that from then on all believers would live as monks, mystically transfigured and full of praise for God, for a thousand years until Judgment Day would put an end to the history of our planet.

Joachim of Fiore's divisions of historical time also highly influenced the New Age movement, which transformed the Three Ages philosophy into astrological terminology, relating the Northern-hemisphere vernal equinox to different constellations of the zodiac. In this scenario the Age of the Father was recast[by whom?] as the Age of Aries, the Age of the Son became the Age of Pisces, and the Age of the Holy Spirit was called the Aquarian New Age. The current so-called "Age of Aquarius" will supposedly witness the development of a number of great changes for humankind,[33] reflecting the typical features of some manifestations of millennialism.[34]

See also[]

- Christian eschatology

- Christian Zionism

- Council of Ephesus

- Cult of the Holy Spirit

- Immanentize the eschaton

- Millenarianism

- Millennial Day Theory

- Preterism

- The Pursuit of the Millennium

- Year 1000

- Year 6000

References[]

- ^ Some examples are given by Gerschom Scholem in Sabbatai Sevi, the mystical messiah (London: Routledge, 1973). The whole book profiles a Jewish group of this kind centered on the person of Sabbatai Zevi, but in part 1 Scholem also gives a number of comparable Christian examples, e.g. p. 100 - 101.

- ^ The Kitáb-i-Íqán, pg. 199.

- ^ McMullen, Michael D. (2000). The Baha'i: The Religious Construction of a Global Identity. Atlanta, Georgia: Rutgers University Press. p. 7. ISBN 0-8135-2836-4.

- ^ The Kitáb-i-Aqdas, gr. 37.

- ^ Theology Today, January 1996, Vol. 53, No. 4, pp. 464–476. On-line version here.

- ^ Eusebius. Church History (Book III).

- ^ Damick, Fr. Andrew Stephen (2011), Orthodoxy and Heterodoxy, Chesterton, IN: Ancient Faith Publishing, p. 23, ISBN 978-1-936270-13-2

- ^ Luke 1:33 and Stuart Hall, Doctrine and Practice of the Early Church (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1992), 171.

- ^ Kirsch J.P. Transcribed by Donald J. Boon. Millennium and Millenarianism

- ^ Philippe Bobichon, "Millénarisme et orthodoxie dans les écrits de Justin Martyr" in Mélanges sur la question millénariste de l’Antiquité à nos jours, Martin Dumont (dir.) [Bibliothèque d'étude des mondes chrétiens, 11], Paris, 2018, pp. 61-82 online

- ^ "Western Reformed Seminary". www.wrs.edu.

- ^ "Dr F N Lee - Sermon". www.dr-fnlee.org.

- ^ "CHURCH FATHERS: Dialogue with Trypho, Chapters 69-88 (Justin Martyr)". www.newadvent.org.

- ^ Taylor, Voice of the Church, P. 66; Peters, Theocratic Kingdom, 1:495; Walvoord, Millennial Kingdom, p. 120; et al.

- ^ Richard Cunningham Shimeall, Christ's Second Coming: Is it Pre-Millennial or Post-Millennial? (New York: John F. Trow, 1865), p. 67. See also, Taylor, p. 66; Peters, 1:495; Jesse Forest Silver, The Lord’s Return (New York, et al.: Fleming H. Revell Co., 1914), p. 66; W. Chillingworth, The Works of W. Chillingworth, 12th ed. (London: B. Blake, 1836), p.714; et al.

- ^ Gawrisch, Wilbert (1998). Eschatological Prophecies and Current Misinterpretations in Our Great Heritage, Volume 3. Milwaukee: Northwestern Publishing House. pp. 688–689. ISBN 0810003791.

- ^ "Primary Sources - Apocalypse! FRONTLINE - PBS". www.pbs.org.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church. Imprimatur Potest +Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger. Doubleday, NY 1995, p. 194.

- ^ Studies in the Scriptures, Volume One, The Divine Plan of the Ages, Study IX, "Ransom and Restitution," pp. 149-152

- ^ "Who Goes to Heaven?". . Archived from the original on 29 May 2021. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ^ Dunn, Emily (27 May 2015). Lightning from the East: Heterodoxy and Christianity in Contemporary China. ISBN 9789004297258.

- ^

Compare:

Tabor, James D. (2011). "13: Ancient Jewish and Early Christian Millennialism". In Wessinger, Catherine (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Millennialism. Oxford Handbooks (reprint ed.). New York: Oxford University Press (published 2016). p. 254. ISBN 9780190611941. Retrieved 2019-02-05.

Millennialism, as it developed in emerging forms of Judaism around 200 B.C.E., was a response to a much older conceptual problem and a specific historical crisis brought on by a program of Hellenization initiated by the Macedonian ruler, Antiochus IV (r. 175-164 B.C.E.), a successor of Alexander the Great (256-323 B.C.E.), who had conquered Syria-Palestine in 332 B.C.E.

- ^ Gerschom Scholem, Sabbatai Sevi, the mystical messiah (London: Routledge, 1973). Scholem also gives examples of other Jewish millennialist movements.

- ^ Bailey, Alice A. The Externalisation of the Hierarchy New York:1957 Lucis Publishing Co. Page 530

- ^ Bailey, Alice A. The Reappearance of the Christ New York:1948 Lucis Publishing Co.

- ^

Bromley, David G. (2003). "Violence and New Religious Movements". In Lewis, James R. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of New Religious Movements. Oxford Handbooks in Religion and Theology. 1 (reprint ed.). New York: Oxford University Press (published 2008). p. 148. ISBN 9780195369649. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

Groups with millennial/apocalyptic expectations have been proposed to be prone to violence due to their fiery rhetoric condemning the existing social order and separation from that order. [...] However, there does not appear to be any simple connection between millennialism and violence. [...] While millennialism as a general form may not be linked to violence, there have been several suggestions that specific types of millennialism may be so connected.

- ^

Compare:

Walliss, John (2011). "Fragile Millennial Communities and Violence". In Wessinger, Catherine (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Millennialism. Oxford Handbooks Series (reprint ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press (published 2016). p. 224. ISBN 9780190611941. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

Like all religious groups, Wessinger argues, millennial groups possess an 'ultimate concern' [...] When this concern - or 'millennial goal' - is threatened in some way, a group that possesses a radically dualistic perspective may in some cases seek to preserve or fulfill their goal through acts of violence. [...] By contrast, revolutionary millennial movements are likely to engage in pre-emptive, offensive actions, believing 'that revolutionary violence is necessary to become liberated from their persecutors and to set up the righteous government and society' [...]. [...] Finally, [...] Wessinger adds the category of fragile millennial groups, where violence stems from a combination of internal pressures and the perception or experience of external opposition.

- ^

Bromley, David G. (2003). "Violence and New Religious Movements". In Lewis, James R. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of New Religious Movements. Oxford Handbooks in Religion and Theology. 1 (reprint ed.). New York: Oxford University Press (published 2008). p. 148. ISBN 9780195369649. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

With progressive millennialism, transformation of the social order is gradual and humans play a role in fostering that transformation.

- ^

Bromley, David G. (2003). "Violence and New Religious Movements". In Lewis, James R. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of New Religious Movements. Oxford Handbooks in Religion and Theology. 1 (reprint ed.). New York: Oxford University Press (published 2008). p. 148. ISBN 9780195369649. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

Catastrophic millennialism deems the current social order as irrevocably corrupt, and total destruction of this order is necessary as the precursor to the building of a new, godly order.

- ^ Lewis (2004). Lewis, James R. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of New Religious Movements. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-514986-6.

- ^ Schmitz-Berning, Cornelia (2000). Vokabular des Nationalsozialismus. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co. KG, 10875 Berlin, pp. 159–160. (in German) [1]

- ^

LeFrois, Bernard J. Eschatological Interpretation of the Apocalypse. The Catholic Biblical Quarterly, Vol. XIII, pp. 17–20; Cited in: Culleton R. G. The Reign of Antichrist, 1951. Reprint TAN Books, Rockford (IL), 1974, p. 9 and in:

Culleton, R. Gerald (1951). The Reign of Antichrist. TAN Books (published 2009). ISBN 9781505102918. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

[...] Since the Holy Office decreed (July 21, 1944) that it cannot be safely taught that Christ at His Second Coming will reign visibly with only some of His saints (risen from the dead) for a period of time before the final and universal judgment, a spiritual millenium is to be seen in Apoc. 20:4–6. St. John gives a recapitulation of the activity of Satan, and the spiritual reign of the saints with Christ in heaven and in His Church on earth.

- ^

Bogdan, Henrik (5 September 2012). "Envisioning the Birth of a New Aeon: Dispensationalism and Millenarianism in the Thelemic Tradition". In Bogdan, Henrik; Starr, Martin P. (eds.). Aleister Crowley and Western Esotericism. Oxford: Oxford University Press (published 2012). ISBN 9780199996063. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

The New Age was commonly also defined in astrological terms, with the Age of Pisces said to be supplanted by the Age of Aquarius. The consequent evolutionary leap in the development of humankind was often portrayed as heralding a fundamental change in the understanding of the relationship between human beings and the universe. Such thought culminated in the blossoming of the New Age movement of the 1960s and early 1970s, with its characterization of the Age of Aquarius as the embodiment of holistic principles [...]. [...] the New Age would be marked by peace and harmony.

- ^

Compare:

Landes, Richard (2006). "Millenarianism and the Dynamics of Apocalyptic Time". In Newport, Kenneth G. C.; Gribben, Crawford (eds.). Expecting the End: Millennialism in Social and Historical Context. Waco, Texas: Baylor University Press. p. 11. ISBN 9781932792386. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

Transformational millennialism tends to foster programs of radical and often unrealistic social change [...]. [...] Currently, the most prominent form of transformational millennialism comes from the New Age movements set in motion by the millennial wave of the 1960s: environmentally harmonized communes.

Bibliography[]

- Barkun, Michael. Disaster and the Millennium (Yale University Press, 1974) (ISBN 0-300-01725-1)

- Case, Shirley J. The Millennial Hope, The University of Chicago Press, 1918.

- Cohn, Norman. The Pursuit of the Millennium: Revolutionary Millenarians and Mystical Anarchists of the Middle Ages, (2nd ed. Yale U.P., 1970).

- Desroches, Henri, Dieux d'hommes. Dictionnaire des messianismes et millénarismes de l'ère chrétienne, The Hague: Mouton, 1969,

- Ellwood, Robert. "Nazism as a Millennialist Movement", in Catherine Wessinger (ed.), Millennialism, Persecution, and Violence: Historical Cases (Syracuse University Press, 2000). (ISBN 0-8156-2809-9 or ISBN 0-8156-0599-4)

- Fenn, Richard K. The End of Time: Religion, Ritual, and the Forging of the Soul (Pilgrim Press, 1997). (ISBN 0-8298-1206-7 or ISBN 0-281-04994-7)

- Hall, John R. Apocalypse: From Antiquity to the Empire of Modernity, (Cambridge, UK: Polity 2009). (ISBN 978-0-7456-4509-4 [pb] and ISBN 978-0-7456-4508-7)

- Kaplan, Jeffrey. Radical Religion in America: Millenarian Movements from the Far Right to the Children of Noah (Syracuse University Press, 1997). (ISBN 0-8156-2687-8 or ISBN 0-8156-0396-7)

- Landes, Richard. Heaven on Earth: The Varieties of the Millennial Experience, (Oxford University Press 2011)

- Pentecost, J. Dwight. Things to Come: A study in Biblical Eschatology(Zondervan, 1958) ISBN 0-310-30890-9 and ISBN 978-0-310-30890-4.

- Redles, David. Hitler's Millennial Reich: Apocalyptic Belief and the Search for Salvation (New York University Press, 2005). (ISBN 978-0-8147-7621-6 or ISBN 978-0-8147-7524-0)

- Stone, Jon R., ed. Expecting Armageddon: Essential Readings in Failed Prophecy (Routledge, 2000). (ISBN 0-415-92331-X)

- Underwood, Grant. (1999) [1993]. The Millenarian World of Early Mormonism. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0252068263

- Wessinger, Catherine. ed. The Oxford Handbook of Millennialism (Oxford University Press, 2011) 768 pp. ISBN 978-0-19-530105-2 online review

- Wistrich, Robert. Hitler’s Apocalypse: Jews and the Nazi Legacy (St. Martin's Press, 1985). (ISBN 0-312-38819-5)

- Wojcik, Daniel (1997). The End of the World as We Know It: Faith, Fatalism, and Apocalypse in America. New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-9283-9.

External links[]

- Book of Revelation

- Christian eschatology

- Christian terminology