Solar flare

| Heliophysics |

|---|

| Phenomena |

|

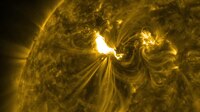

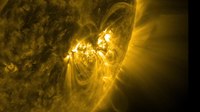

A solar flare is a sudden flash of increased brightness on the Sun, usually observed near its surface and in close proximity to a sunspot group. Powerful flares are often, but not always, accompanied by a coronal mass ejection. Even the most powerful flares are barely detectable in the total solar irradiance (the "solar constant").[1]

Solar flares occur in a power-law spectrum of magnitudes; an energy release of typically 1020 joules of energy suffices to produce a clearly observable event, while a major event can emit up to 1025 joules.[2] Although originally observed in the visible electromagnetic spectrum, especially in the Hα emission line of hydrogen, they can now be detected from radio waves to gamma-rays.

Flares are closely associated with the ejection of plasmas and particles through the Sun's corona into interplanetary space; flares also copiously emit radio waves. If the ejection is in the direction of the Earth, particles associated with this disturbance can penetrate into the upper atmosphere (the ionosphere) and cause bright auroras, and may even disrupt long range radio communication. It usually takes days for the solar plasma ejecta to reach Earth.[3] Flares also occur on other stars, where the term stellar flare applies. High-energy particles, which may be relativistic, can arrive almost simultaneously with the electromagnetic radiations.

Description[]

Solar flares affect all layers of the solar atmosphere (photosphere, chromosphere, and corona). The plasma medium is heated to tens of millions of kelvins, while electrons, protons, and heavier ions are accelerated to near the speed of light. Flares produce electromagnetic radiation across the electromagnetic spectrum at all wavelengths, from radio waves to gamma rays. Most of the energy is spread over frequencies outside the visual range; the majority of the flares are not visible to the naked eye and must be observed with special instruments. Flares occur in active regions around sunspots, where intense magnetic fields penetrate the photosphere to link the corona to the solar interior. Flares are powered by the sudden (timescales of minutes to tens of minutes) release of magnetic energy stored in the corona. The same energy releases may produce coronal mass ejections (CMEs), although the relationship between CMEs and flares is still not well understood.

X-rays and UV radiation emitted by solar flares can affect Earth's ionosphere and disrupt long-range radio communications. Direct radio emission at decimetric wavelengths may disturb the operation of radars and other devices that use those frequencies.

Solar flares were first observed on the Sun by Richard Christopher Carrington and independently by Richard Hodgson in 1859[4] as localized visible brightenings of small areas within a sunspot group. Stellar flares can be inferred by looking at the lightcurves produced from the telescope or satellite data of variety of other stars.

The frequency of occurrence of solar flares varies following the 11-year solar cycle. It can range from several per day during solar maximum to less than one every week during solar minimum. Large flares are less frequent than smaller ones.

Cause[]

Flares occur when accelerated charged particles, mainly electrons, interact with the plasma medium. Evidence suggests that the phenomenon of magnetic reconnection leads to this extreme acceleration of charged particles.[5] On the Sun, magnetic reconnection may happen on solar arcades – a series of closely occurring loops following magnetic lines of force. These lines of force quickly reconnect into a lower arcade of loops leaving a helix of magnetic field unconnected to the rest of the arcade. The sudden release of energy in this reconnection is the origin of the particle acceleration. The unconnected magnetic helical field and the material that it contains may violently expand outwards forming a coronal mass ejection.[6] This also explains why solar flares typically erupt from active regions on the Sun where magnetic fields are much stronger.

Although there is a general agreement on the source of a flare's energy, the mechanisms involved are still not well understood. It's not clear how the magnetic energy is transformed into the kinetic energy of the particles, nor is it known how some particles can be accelerated to the GeV range (109 electron volt) and beyond. There are also some inconsistencies regarding the total number of accelerated particles, which sometimes seems to be greater than the total number in the coronal loop. Scientists are unable to forecast flares.[citation needed]

Classification[]

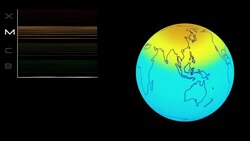

The classification system for solar flares uses the letters A, B, C, M or X, according to the peak flux in watts per square metre (W/m2) of X-rays with wavelengths 100 to 800 picometres (1 to 8 ångströms), as measured at the Earth by the GOES spacecraft.

| Classification | Approximate peak flux range at 100–800 picometre (watts/square metre) |

|---|---|

| A | < 10−7 |

| B | 10−7 – 10−6 |

| C | 10−6 – 10−5 |

| M | 10−5 – 10−4 |

| X | > 10−4 |

The strength of an event within a class is noted by a numerical suffix ranging from 0 to 9, which is also the factor for that event within the class. Hence, an X2 flare is twice the strength of an X1 flare, an X3 flare is three times as powerful as an X1, and only 50% more powerful than an X2.[8] An X2 is four times more powerful than an M5 flare.[9]

H-alpha classification[]

An earlier flare classification was based on Hα spectral observations. The scheme uses both the intensity and emitting surface. The classification in intensity is qualitative, referring to the flares as: faint (f), normal (n) or brilliant (b). The emitting surface is measured in terms of millionths of the hemisphere and is described below. (The total hemisphere area AH = 15.5 × 1012 km2.)

| Classification | Corrected area (millionths of hemisphere) |

|---|---|

| S | < 100 |

| 1 | 100–250 |

| 2 | 250–600 |

| 3 | 600–1200 |

| 4 | > 1200 |

A flare then is classified taking S or a number that represents its size and a letter that represents its peak intensity, v.g.: Sn is a normal sunflare.[10]

Hazards[]

Solar flares strongly influence the local space weather in the vicinity of the Earth. They can produce streams of highly energetic particles in the solar wind or stellar wind, known as a solar particle event. These particles can impact the Earth's magnetosphere (see main article at geomagnetic storm), and present radiation hazards to spacecraft and astronauts. Additionally, massive solar flares are sometimes accompanied by coronal mass ejections (CMEs) which can trigger geomagnetic storms that have been known to disable satellites and knock out terrestrial electric power grids for extended periods of time.

The soft X-ray flux of X class flares increases the ionization of the upper atmosphere, which can interfere with short-wave radio communication and can heat the outer atmosphere and thus increase the drag on low orbiting satellites, leading to orbital decay.[citation needed] Energetic particles in the magnetosphere contribute to the aurora borealis and aurora australis. Energy in the form of hard X-rays can be damaging to spacecraft electronics and are generally the result of large plasma ejection in the upper chromosphere.

The radiation risks posed by solar flares are a major concern in discussions of a human mission to Mars, the Moon, or other planets. Energetic protons can pass through the human body, causing biochemical damage,[11] presenting a hazard to astronauts during interplanetary travel. Some kind of physical or magnetic shielding would be required to protect the astronauts. Most proton storms take at least two hours from the time of visual detection to reach Earth's orbit. A solar flare on January 20, 2005, released the highest concentration of protons ever directly measured, which would have given astronauts on the moon little time to reach shelter.[12][13]

Observations[]

Flares produce radiation across the electromagnetic spectrum, although with different intensity. They are not very intense in visible light, but they can be very bright at particular spectral lines. They normally produce bremsstrahlung in X-rays and synchrotron radiation in radio.

History[]

Optical observations[]

Richard Carrington observed a flare for the first time on 1 September 1859 projecting the image produced by an optical telescope through a broad-band filter. It was an extraordinarily intense white light flare. Since flares produce copious amounts of radiation at Hα, adding a narrow ( ≈1 Å) passband filter centered at this wavelength to the optical telescope allows the observation of not very bright flares with small telescopes. For years Hα was the main, if not the only, source of information about solar flares. Other passband filters are also used.

Radio observations[]

During World War II, on February 25 and 26, 1942, British radar operators observed radiation that Stanley Hey interpreted as solar emission. Their discovery did not go public until the end of the conflict. The same year Southworth also observed the Sun in radio, but as with Hey, his observations were only known after 1945. In 1943 Grote Reber was the first to report radioastronomical observations of the Sun at 160 MHz. The fast development of radioastronomy revealed new peculiarities of the solar activity like storms and bursts related to the flares. Today ground-based radiotelescopes observe the Sun from c. 15 MHz up to 400 GHz.

Space telescopes[]

Since the beginning of space exploration, telescopes have been sent to space, where detect wavelengths shorter than UV, which are completely absorbed by the Earth's atmosphere, and where flares may be very bright. Since the 1970s, the GOES series of satellites observe the Sun in soft X-rays, and their observations became the standard measure of flares, diminishing the importance of the Hα classification. Hard X-rays were observed by many different instruments, the most important today being the Reuven Ramaty High Energy Solar Spectroscopic Imager (RHESSI). Nonetheless, UV observations are today the stars of solar imaging with their incredible fine details that reveal the complexity of the solar corona. Spacecraft may also bring radio detectors at extremely long wavelengths (as long as a few kilometers) that cannot propagate through the ionosphere.

Optical telescopes[]

- Big Bear Solar Observatory, located in Big Bear Lake, California and operated by the New Jersey Institute of Technology, is a solar dedicated observatory with different instruments, as well as a huge data bank of full disk Hα images.[14]

- Swedish 1-m Solar Telescope, operated by the Institute for Solar Physics (Sweden), is located in the Observatorio del Roque de los Muchachos on the island of La Palma (Spain).

- McMath-Pierce Solar Telescope, located at Kitt Peak National Observatory in Arizona, is the world's largest solar telescope.

Radio telescopes[]

- Nançay Radioheliographe (NRH) is an interferometer composed of 48 antennas observing at meter-decimeter wavelengths. The radioheliographe is installed at the Nançay Radio Observatory, France.[15]

- Owens Valley Solar Array (OVSA) is a radio interferometer operated by the New Jersey Institute of Technology originally consisting of 7 antennas, observing from 1 to 18 GHz in both left and right circular polarization. OVSA is located in Owens Valley, California. It is now called Expanded Owens Valley Solar Array (EOVSA) after the expansion to upgrade its control system and increase the total number of antennas to 15.[16]

- Nobeyama Radioheliograph (NoRH) is an interferometer installed at the Nobeyama Radio Observatory, Japan, formed by 84 small (80 cm) antennas, with receivers at 17 GHz (left and right polarization) and 34 GHz operating simultaneously. It continuously observes the Sun, producing daily snapshots.[17]

- Siberian Solar Radio Telescope (SSRT) is a special-purpose solar radio telescope designed for studying solar activity in the microwave range (5.7 GHz) where the processes occurring in the solar corona are accessible to observation over the entire solar disk. It is a crossed interferometer, consisting of two arrays of 128x128 parabolic antennas 2.5 meters in diameter each, spaced equidistantly at 4.9 meters and oriented in the E-W and N-S directions. It is located in a wooded valley separating two mountain ridges of the Eastern Sayan Mountains and Khamar-Daban, 220 km from Irkutsk, Russia.[18]

- Nobeyama Radio Polarimeters are a set of radio telescopes installed at the Nobeyama Radio Observatory that continuously observes the full Sun (no images) at the frequencies of 1, 2, 3.75, 9.4, 17, 35, and 80 GHz, at left and right circular polarization.[19]

- Solar Submillimeter Telescope is a single dish telescope, that observes continuously the Sun at 212 and 405 GHz. It is installed at Complejo Astronomico El Leoncito in Argentina. It has a focal array composed by 4 beams at 212 GHz and 2 at 405 GHz, therefore it can instantaneously locate the position of the emitting source[20] SST is the only solar submillimeter telescope currently in operation.

- Polarization Emission of Millimeter Activity at the Sun (POEMAS) is a system of two circular polarization solar radio telescopes, for observations of the Sun at 45 and 90 GHz. The novel characteristic of these instruments is the capability to measure circular right- and left-hand polarizations at these high frequencies. The system is installed at Complejo Astronomico El Leoncito in Argentina. It started operations in November 2011. In November 2013 it went offline for repairs. It is expected to return to observing in January 2015.

- Bleien Radio Observatory is a set of radio telescopes operating near Gränichen (Switzerland). They continuously observe the solar flare radio emission from 10 MHz (ionospheric limit) to 5 GHz. The broadband spectrometers are known as Phoenix and CALLISTO.[21]

Space telescopes[]

The following spacecraft missions have flares as their main observation target.

- Yohkoh – The Yohkoh (originally Solar A) spacecraft observed the Sun with a variety of instruments from its launch in 1991 until its failure in 2001. The observations spanned a period from one solar maximum to the next. Two instruments of particular use for flare observations were the Soft X-ray Telescope (SXT), a glancing incidence low energy X-ray telescope for photon energies of order 1 keV, and the Hard X-ray Telescope (HXT), a collimation counting instrument which produced images in higher energy X-rays (15–92 keV) by image synthesis.

- WIND – The Wind spacecraft is devoted to the study of the interplanetary medium. Since the Solar Wind is its main driver, solar flares effects can be traced with the instruments aboard Wind. Some of the WIND experiments are: a very low frequency spectrometer, (WAVES), particles detectors (EPACT, SWE) and a magnetometer (MFI).

- GOES – The GOES spacecraft are satellites in geostationary orbits around the Earth that have measured the soft X-ray flux from the Sun since the mid-1970s, following the use of similar instruments on the Solrad satellites. GOES X-ray observations are commonly used to classify flares, with A, B, C, M, and X representing different powers of ten – an X-class flare has a peak 1–8 Å flux above 0.0001 W/m2.

- RHESSI – The Reuven Ramaty High Energy Solar Spectral Imager was designed to image solar flares in energetic photons from soft X rays (ca. 3 keV) to gamma rays (up to ca. 20 MeV) and to provide high resolution spectroscopy up to gamma-ray energies of ca. 20 MeV. Furthermore, it had the capability to perform spatially resolved spectroscopy with high spectral resolution. It was decommissioned in August 2018, after more than 16 years of operation.

- SOHO – The Solar and Heliospheric Observatory is collaboration between the ESA and NASA which is in operation since December 1995. It carries 12 different instruments, among them the Extreme ultraviolet Imaging Telescope (EIT), the Large Angle and Spectrometric Coronagraph (LASCO) and the Michelson Doppler Imager (MDI). SOHO is in a halo orbit around the earth-sun L1 point.

- TRACE – The Transition Region and Coronal Explorer is a NASA Small Explorer program (SMEX) to image the solar corona and transition region at high angular and temporal resolution. It has passband filters at 173 Å, 195 Å, 284 Å, 1600 Å with a spatial resolution of 0.5 arc sec, the best at these wavelengths.

- SDO – The Solar Dynamics Observatory is a NASA project composed of 3 different instruments: the Helioseismic and Magnetic Imager (HMI), the Atmospheric Imaging Assembly (AIA) and the Extreme Ultraviolet Variability Experiment (EVE). It has been operating since February 2010 in a geosynchronous earth orbit.[22]

- Hinode –The Hinode spacecraft, originally called Solar B, was launched by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency in September 2006 to observe solar flares in more precise detail. Its instrumentation, supplied by an international collaboration including Norway, the U.K., the U.S., and Africa focuses on the powerful magnetic fields thought to be the source of solar flares. Such studies shed light on the causes of this activity, possibly helping to forecast future flares and thus minimize their dangerous effects on satellites and astronauts.[23]

- ACE – The Advanced Composition Explorer was launched in 1997 into a halo orbit around the Earth–Sun L1 point. It carries spectrometers, magnetometers and charged particle detectors to analyze the solar wind. The Real Time Solar Wind (RTSW) beacon is continually monitored by a network of NOAA-sponsored ground stations to provide early warning of earth-bound CMEs.

- MAVEN – The Mars Atmosphere and Volatile EvolutioN (MAVEN) mission, which launched from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station on November 18, 2013, is the first mission devoted to understanding the Martian upper atmosphere. The goal of MAVEN is to determine the role that loss of atmospheric gas to space played in changing the Martian climate through time. The Extreme Ultraviolet (EUV) monitor on MAVEN is part of the Langmuir Probe and Waves (LPW) instrument and measures solar EUV input and variability, and wave heating of the Martian upper atmosphere.[24]

- STEREO – The Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory is a solar observation mission consisting of two nearly identical spacecraft that were launched in 2006. Contact with STEREO-B was lost in 2014, but STEREO-A is still operational. Each spacecraft carries several instruments, including cameras, particle detectors and a radio burst tracker.

In addition to these solar observing facilities, many non-solar astronomical satellites observe flares either intentionally (e.g., NuSTAR), or simply because the penetrating hard radiations coming from a flare can readily penetrate most forms of shielding.

Examples of large solar flares[]

The most powerful flare ever observed was the first one to be observed,[26] on September 1, 1859, and was reported by British astronomer Richard Carrington and independently by an observer named Richard Hodgson. The event is named the Solar storm of 1859, or the "Carrington event". The flare was visible to a naked eye (in white light), and produced stunning auroras down to tropical latitudes such as Cuba or Hawaii, and set telegraph systems on fire.[27] The flare left a trace in Greenland ice in the form of nitrates and beryllium-10, which allow its strength to be measured today.[28] Cliver and Svalgaard[29] reconstructed the effects of this flare and compared with other events of the last 150 years. In their words: "While the 1859 event has close rivals or superiors in each of the above categories of space weather activity, it is the only documented event of the last ∼150 years that appears at or near the top of all of the lists." The intensity of the flare has been estimated to be around X50.[30]

The ultra-fast coronal mass ejection of August 1972 is suspected of triggering magnetic fuses on naval mines during the Vietnam War, and would have been a life-threatening event to Apollo astronauts if it had occurred during a mission to the Moon.[31][32]

In modern times, the largest solar flare measured with instruments occurred on November 4, 2003. This event saturated the GOES detectors, and because of this its classification is only approximate. Initially, extrapolating the GOES curve, it was estimated to be X28.[33] Later analysis of the ionospheric effects suggested increasing this estimate to X45.[34] This event produced the first clear evidence of a new spectral component above 100 GHz.[35]

Other large solar flares also occurred on April 2, 2001 (X20),[36] October 28, 2003 (X17.2 and 10),[37] September 7, 2005 (X17),[36] February 17, 2011 (X2),[38][39][40] August 9, 2011 (X6.9),[41][42] March 7, 2012 (X5.4),[43][44] July 6, 2012 (X1.1).[45] On July 6, 2012, a solar storm hit just after midnight UK time,[46] when an X1.1 solar flare fired out of the AR1515 sunspot. Another X1.4 solar flare from AR 1520 region of the Sun,[47] second in the week, reached the Earth on July 15, 2012[48] with a geomagnetic storm of G1–G2 level.[49][50] A X1.8-class flare was recorded on October 24, 2012.[51] There has been major solar flare activity in early 2013, notably within a 48-hour period starting on May 12, 2013, a total of four X-class solar flares were emitted ranging from an X1.2 and upwards of an X3.2,[52] the latter of which was one of the largest year 2013 flares.[53][54] Departing sunspot complex AR2035-AR2046 erupted on April 25, 2014, at 0032 UT, producing a strong X1.3-class solar flare and an HF communications blackout on the day-side of Earth. NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory recorded a flash of extreme ultraviolet radiation from the explosion. The Solar Dynamics Observatory recorded an X9.3-class flare at around 1200 UTC on September 6, 2017.[55]

On July 23, 2012, a massive, potentially damaging,[vague] solar storm (solar flare, coronal mass ejection and electromagnetic radiation) barely missed Earth.[56][57] In 2014, Pete Riley of Predictive Science Inc. published a paper in which he attempted to calculate the odds of a similar solar storm hitting Earth within the next 10 years, by extrapolating records of past solar storms from the 1960s to the present day. He concluded that there may be as much as a 12% chance of such an event occurring.[56]

Flare spray[]

Flare sprays are a type of eruption associated with solar flares.[58] They involve faster ejections of material than eruptive prominences,[59] and reach velocities of 20 to 2000 kilometers per second.[60]

Flare periodicity[]

Erich Rieger discovered with coworkers in 1984 a ~154 days period in hard solar flares at least since the solar cycle 19.[61] The period has since been confirmed in most heliophysics data and the interplanetary magnetic field and is commonly known as the Rieger period. The period's resonance harmonics also have been reported from most data types in the heliosphere. Possible causes of this solar wind resonance include influences of planetary constellations on the Sun.

Prediction[]

Current methods of flare prediction are problematic, and there is no certain indication that an active region on the Sun will produce a flare. However, many properties of sunspots and active regions correlate with flaring. For example, magnetically complex regions (based on line-of-sight magnetic field) called delta spots produce the largest flares. A simple scheme of sunspot classification due to McIntosh, or related to fractal complexity[62] is commonly used as a starting point for flare prediction.[63] Predictions are usually stated in terms of probabilities for occurrence of flares above M or X GOES class within 24 or 48 hours. The U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) issues forecasts of this kind.[64] MAG4 was developed at the University of Alabama in Huntsville with support from the Space Radiation Analysis Group at Johnson Space Flight Center (NASA/SRAG) for forecasting M and X class flares, CMEs, fast CME, and Solar Energetic Particle events.[65] A physics-based method that can predict imminent large solar flares was proposed by Institute for Space-Earth Environmental Research (ISEE), Nagoya University.[66]

See also[]

- Aurora

- Coronal cloud

- Flare star

- Gamma-ray burst

- Hyder flare

- List of plasma (physics) articles

- List of solar storms

- Magnetic cloud

- Moreton wave

- Neupert effect

- Rieger period

- Superflare

- Supra-arcade downflows

References[]

- ^ Kopp, G.; Lawrence, G.; Rottman, G. (2005). "The Total Irradiance Monitor (TIM): Science Results". Solar Physics. 20 (1–2): 129–139. Bibcode:2005SoPh..230..129K. doi:10.1007/s11207-005-7433-9.

- ^ "What is a Solar Flare?". NASA. Retrieved May 12, 2016.

- ^ Menzel, Whipple, and de Vaucouleurs, "Survey of the Universe", 1970

- ^ "Description of a Singular Appearance seen in the Sun on September 1, 1859", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, v20, pp13+, 1859

- ^ Zhu et al., ApJ, 2016, 821, L29

- ^ "The Mysterious Origins of Solar Flares", Scientific American, April 2006

- ^ "Great Ball of Fire". NASA. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ Garner, Rob (6 September 2017). "Sun Erupts With Significant Flare". NASA. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- ^ Schrijver, Carolus J.; Siscoe, George L., eds. (2010), Heliophysics: Space Storms and Radiation: Causes and Effects, Cambridge University Press, p. 375, ISBN 978-1107049048

- ^ Tandberg-Hanssen, Einar; Emslie, A. Gordon (1988). Cambridge University Press (ed.). "The physics of solar flares".

- ^ "New Study Questions the Effects of Cosmic Proton Radiation on Human Cells". Archived from the original on 2008-10-06. Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- ^ "A New Kind of Solar Storm – NASA Science". nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 2010-03-23.

- ^ R.A. Mewaldt; et al. (May 2005). "Space Weather Implications of the 20 January 2005 Solar Energetic Particle Event". Paper at American Geophysical Union meeting.

- ^ "Big Bear Solar Observatory." New Jersey Institute of Technology. Retrieved: 18 June 2017.

- ^ "Station de Radioastronomie de Nançay". www.obs-nancay.fr. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- ^ "OVSA Expanstion Project." New Jersey Institute of Technology. Retrieved: 18 June 2017.

- ^ "Nobeyama Radioheliograph." Nobeyama Radio Observatory. Retrieved: 18 June 2017.

- ^ "The Siberian Solar Radio Telescope – ISTP SB RAS". en.iszf.irk.ru. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- ^ "Nobeyama Radio Polarimeters." Nobeyama Radio Observatory. Retrieved: 18 June 2017.

- ^ Gimenez de Castro, C.G., Raulin, J.-P., Makhmutov, V., Kaufmann, P., Csota, J.E.R., Instantaneous positions of microwave solar bursts: Properties and validity of the multiple beam observations Astron. Astrophys. Suppl. Ser., 140, 3, December II 1999 doi:10.1051/aas:1999428

- ^ "Radioastronomy FHNW". soleil.i4ds.ch. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- ^ "About the SDO Mission" Solar Dynamics Observatory. Retrieved: 15 July 2013.

- ^ "Japan launches Sun 'microscope'". BBC. 2006-09-23. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ "MAVEN". Retrieved 2019-06-02.

- ^ "Extreme Space Weather Events". National Geophysical Data Center. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ "A Super Solar Flare". NASA. 6 May 2008. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- ^ Bell, Trudy E.; Phillips, Tony (2008). "A Super Solar Flare". Science@NASA. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ Battersby, Stephen (21 March 2005). "Superflares could kill unprotected astronauts". New Scientist. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- ^ Cliver, E.W.; Svalgaard, L. (2004). "The 1859 solar–terrestrial disturbance and the current limits of extreme space weather activity" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-08-11. Retrieved 2011-04-22.

- ^ Woods, Tom. "Solar Flares" (PDF). Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- ^ Knipp, Delores J.; Fraser, Brian J.; Shea, M. A.; Smart, D. F. (October 25, 2018). "On the Little-Known Consequences of the 4 August 1972 Ultra-Fast Coronal Mass Ejecta: Facts, Commentary, and Call to Action". Space Weather. 16 (11): 1635–1643. doi:10.1029/2018SW002024.

- ^ "Solar Storm and Space Weather—Frequently Asked Questions". NASA Mission Pages: Sun-Earth. Retrieved November 12, 2018.

- ^ "SOHO Hotshots". Sohowww.nascom.nasa.gov. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ "Biggest ever solar flare was even bigger than thought | SpaceRef – Your Space Reference". SpaceRef. 2004-03-15. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ Kaufmann, Pierre; Raulin, Jean-Pierre; Giménez de Castro, C. G.; Levato, Hugo; Gary, Dale E.; Costa, Joaquim E. R.; Marun, Adolfo; Pereyra, Pablo; Silva, Adriana V. R.; Correia, Emilia (March 10, 2004). "A new solar burst spectral component emitting only in the terahertz range" (PDF). The Astrophysical Journal. 603 (2): 121–124. Bibcode:2004ApJ...603L.121K. doi:10.1086/383186. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "BIGGEST SOLAR X-RAY FLARE ON RECORD – X20". NASA. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ "X 17.2 AND 10.0 FLARES!". NASA. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ Hendrix, Susan (2012-03-07). "Valentine's Day Solar Flare" (video included). Nasa Goddard Space Flight Center. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ "Solar flare to jam Earth's communications". ABC. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ Kremer, Ken. "Sun Erupts with Enormous X2 Solar Flare". Universe Today. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ Fox, Karen C.; Hendrix, Susan (August 9, 2011). "Sun Unleashes X6.9 Class Flare". NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. Retrieved April 10, 2021.

- ^ Bergen, Jennifer. "Sun fires powerful X6.9-class solar flare". Geek.com. Archived from the original on October 18, 2012. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ Zalaznick, Matt. "Gimme Some Space: Solar Flare, Solar Storm Strike". The Norwalk Daily Voice. Retrieved July 19, 2012.

- ^ "Geomagnetic Storm Strength Increases". NASA. Retrieved July 9, 2012.

- ^ Fox, Karen (July 7, 2012). "Sunspot 1515 Release X1.1 Class Solar Flare". Nasa Goddard Space Flight Center. Retrieved July 14, 2012.

- ^ "Massive 'X Class' Solar Flare Bursts From Sun, Causing Radio Blackouts (VIDEO)". Huffington Post UK. July 9, 2012. Retrieved July 14, 2012.

- ^ "Big Sunspot 1520 Releases X1.4 Class Flare With Earth-Directed CME". NASA. July 12, 2012. Retrieved July 14, 2012.

- ^ "Solar storm rising, to hit Earth today". The Times of India. Archived from the original on November 11, 2013. Retrieved July 14, 2012.

- ^ "'Minor' solar storm reaches Earth". aljazeera.com. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- ^ "Space Weather Alerts and Warnings Timeline: July 16, 2012". NOAA. Retrieved July 17, 2012.

- ^ "Sun Unleashes Powerful Solar Flare". Sky News. October 24, 2012. Retrieved October 24, 2012.

- ^ "Three X-class Flares in 24 Hours (First Update)". NASA Missions Sun-Earth. May 13, 2013. Retrieved April 10, 2021.

- ^ "Three X-class Flares in 24 Hours (Third Update)". NASA Missions Sun-Earth. May 14, 2013. Retrieved April 10, 2021.

- ^ Malik, Tariq (13 May 2013). "Major Solar Flare Erupts from the Sun, Strongest of 2013". Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- ^ "Two Significant Solar Flares Imaged by NASA's SDO". 6 September 2017. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Phillips, Dr. Tony (July 23, 2014). "Near Miss: The Solar Superstorm of July 2012". NASA. Retrieved July 26, 2014.

- ^ Staff (April 28, 2014). "Video (04:03) – Carrington-class coronal mass ejection narrowly misses Earth". NASA. Retrieved July 26, 2014.

- ^ Morimoto, Tarou; Kurokawa, Hiroki. "Effects of Magnetic and Gravity forces on the Acceleration of Solar Filaments and Coronal Mass Ejections" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-11. Retrieved 2009-10-08.

- ^ Tandberg-Hanssen, E.; Martin, Sara F.; Hansen, Richard T. (March 1980). "Dynamics of flare sprays". Solar Physics. 65 (2): 357–368. doi:10.1007/BF00152799. ISSN 0038-0938.

- ^ "NASA Visible Earth: Biggest Solar Flare on Record". nasa.gov.

- ^ Rieger, E., Share, G. H., Forrest, D. J., Kanbach, G., Reppin, C., Chupp, E. L. (1984) A 154-day periodicity in the occurrence of hard solar flares? Nature 312, 623–625.

- ^ McAteer, James (2005). "Statistics of Active Region Complexy". The Astrophysical Journal. 631 (2): 638. Bibcode:2005ApJ...631..628M. doi:10.1086/432412.

- ^ Wheatland, M. S. (2008). "A Bayesian approach to solar flare prediction". The Astrophysical Journal. 609 (2): 1134–1139. arXiv:astro-ph/0403613. Bibcode:2004ApJ...609.1134W. doi:10.1086/421261.

- ^ "Space Weather Prediction Center". NOAA. Retrieved August 1, 2012.

- ^ Falconer (2011), A tool for empirical forecasting of major flares,coronal mass ejections, and solar particle eventsfrom a proxy of active-region free magnetic energy (PDF)

- ^ Kusano, Kanya; Iju, Tomoya; Bamba, Yumi; Inoue, Satoshi (July 31, 2020). "A physics-based method that can predict imminent large solar flares". Science. 369 (6503): 587–591. Bibcode:2020Sci...369..587K. doi:10.1126/science.aaz2511.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Solar flares. |

- Real-time space weather on the iPhone, iPad, and Android from 150 data streams and 19 institutions.

- Live Solar Images and Data Site Includes x-ray flare, geomagnetic, space weather information detailing current solar events.

- Solar Cycle 24 and VHF Aurora Website (www.solarcycle24.com)

- Solar Weather Site

- Current Solar Flare – and geomagnetic activity in dashboard style (www.solar-flares.info) Archived 2021-02-25 at the Wayback Machine

- STEREO Spacecraft Site

- BBC report on the November 4, 2003 flare

- NASA SOHO observations of flares

- 'The Sun Kings', lecture by Dr Stuart Clark on the discovery of solar flares given at Gresham College, 12 September 2007 (available as a video or audio download as well as a text file).

- NASA Astronomy Picture of the Day: An X Class Flare Region on the Sun (6 November 2007)

- Sun trek website An educational resource for teachers and students about the Sun and its effect on the Earth

- NASA – Carrington Super Flare NASA May 6, 2008

- Archive of the most severe solar storms

- Animated explanation of Solar Flares from the Photosphere Archived 2015-11-16 at the Wayback Machine (University of South Wales)

- 1 min. 35 sec. Mini documentary: How big are solar flares' prominences? A simplified explanation of the size of solar flares' prominences as compared to Earth.

- The Most Powerful Solar Flares Ever Recorded – spaceweather.com (X9+ summary)

- Most Energetic Flares since 1976 (X5.7+ details)

- Davis, Chris. "Tracking the X Flare". Backstage Science. Brady Haran.

- Study solar flares with Sunspot Data. (

)

)

- Solar phenomena

- Space plasmas

- Plasma physics

- Space hazards

- Doomsday scenarios