Great Slave Lake

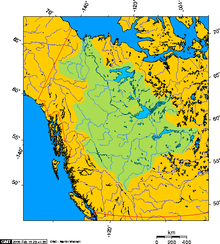

Great Slave Lake[1] (French: Grand lac des Esclaves[5]), known traditionally as Tıdeè in Tłı̨chǫ Yatıì,[6] Tinde’e in Wıìl��ìdeh Yatii / Tetsǫ́t’ıné Yatıé,[7] Tu Nedhé in Dëne Sųłıné Yatıé,[8] and Tucho in Dehcho Dene Zhatıé,[9] is the second-largest lake in the Northwest Territories of Canada (after Great Bear Lake), the deepest lake in North America at 614 metres (336 fathoms; 2,014 ft),[2] and the tenth-largest lake in the world. It is 469 km (291 mi) long and 20 to 203 km (12 to 126 mi) wide.[3] It covers an area of 27,200 km2 (10,502 sq mi)[2] in the southern part of the territory. Its given volume ranges from 1,070 km3 (260 cu mi)[10] to 1,580 km3 (380 cu mi)[2] and up to 2,088 km3 (501 cu mi)[11] making it the 10th or 12th largest by volume.

The lake shares its name with the First Nations peoples of the Dene family called Slavey by their enemies the Cree. Towns situated on the lake include (clockwise from east) Łutselk'e, Fort Resolution, Hay River, Hay River Reserve, Behchokǫ̀, Yellowknife, Ndilǫ, and Dettah. The only community in the East Arm is Łutselk'e, a hamlet of about 350 people, largely Chipewyan Indigenous peoples of the Dene Nation, and the abandoned winter camp and Hudson's Bay Company post, Fort Reliance. Along the south shore, east of Hay River is the abandoned Pine Point Mine and the company town of Pine Point.

History[]

Indigenous peoples were the first settlers around the lake after the retreat of glacial ice. Archaeological evidence has revealed several different periods of cultural history, including Northern Plano Paleoindian tradition (8,000 years before present), Shield Archaic (6,500 years), Arctic small tool tradition (3,500 years), and the Taltheilei Shale Tradition (2,500 years before present). Each culture has left a distinct mark in the archaeological record based on type or size of lithic tools.[12]

Great Slave Lake was put on European maps during the emergence of the fur trade towards the northwest from Hudson Bay in the mid 18th century. The name 'Great Slave' came from the Slavey people, one of the Athabaskan tribes living on its southern shores at that time. The name originated with the Cree enslavement of members of the neighbouring tribe.[13][14][15] As the French explorers dealt directly with the Cree traders, the large lake was referred to as "Grand lac des Esclaves" which was eventually translated into English as "Great Slave Lake".[16]

British fur trader Samuel Hearne explored Great Slave Lake in 1771 and crossed the frozen lake, which he named Lake Athapuscow. In 1897-1898, the American frontiersman Charles "Buffalo" Jones traveled to the Arctic Circle, where his party wintered in a cabin that they had constructed near the Great Slave Lake. Jones's story of how he and his party shot and fended off a hungry wolf pack near Great Slave Lake was verified in 1907 by Ernest Thompson Seton and Edward Alexander Preble when they discovered the remains of the animals near the long abandoned cabin.[17]

In the 1930s, gold was discovered on the North Arm of Great Slave Lake, leading to the establishment of Yellowknife which would become the capital of the NWT. In 1960, an all-season highway was built around the west side of the lake, originally an extension of the Mackenzie Highway but now known as Yellowknife Highway or Highway 3. On January 24, 1978, a Soviet Radar Ocean Reconnaissance Satellite, named Kosmos 954, built with an onboard nuclear reactor fell from orbit and disintegrated. Pieces of the nuclear core fell in the vicinity of Great Slave Lake. Some of the nuclear debris was recovered by a joint Canadian Armed Forces and United States Armed Forces military operation called Operation Morning Light.[18]

Suggested renaming[]

In the late 2010s, many placenames within the Northwest Territories were restored to their indigenous names. It has been suggested that the lake be renamed as well, particularly because of the mention of slavery. "Great Slave Lake is actually a very terrible name, unless you're a proponent of slavery," says Dëneze Nakehk'o, a Northwest Territories educator and founding member of First Nations organization Dene Nahjo.[19] "It's a beautiful place. It's majestic; it's huge. And I don't really think the current name on the map is fitting for that place." He has suggested Tu Nedhé, the Dene Soline name for the lake, as an alternative.[20] Tucho, the Dehcho Dene term for the lake, has also been suggested.[19]

Geography and natural history[]

The Hay, Slave, Lockhart, and Taltson Rivers are its chief tributaries. It is drained by the Mackenzie River. Though the western shore is forested, the east shore and northern arm are tundra-like. The southern and eastern shores reach the edge of the Canadian Shield. Along with other lakes such as the Great Bear and Athabasca, it is a remnant of the vast glacial Lake McConnell.

The lake has a very irregular shoreline. The East Arm of Great Slave Lake is filled with islands, and the area is within the proposed Thaidene Nene National Park Reserve. The Pethei Peninsula separates the East Arm into McLeod Bay in the north and Christie Bay in the south. The lake is at least partially frozen during an average of eight months of the year.

The main western portion of the lake forms a moderately deep bowl with a surface area of 18,500 km2 (7,100 sq mi) and a volume of 596 km3 (143 cu mi). This main portion has a maximum depth of 187.7 m (616 ft) and a mean depth of 32.2 m (106 ft).[21] To the east, McLeod Bay (62°52′N 110°10′W / 62.867°N 110.167°W) and Christie Bay (62°32′N 111°00′W / 62.533°N 111.000°W) are much deeper, with a maximum recorded depth in Christie Bay of 614 m (2,014 ft)[2]

On some of the plains surrounding Great Slave Lake, climax polygonal bogs have formed, the early successional stage to which often consists of pioneer black spruce.[22]

South of Great Slave Lake, in a remote corner of Wood Buffalo National Park, is the Whooping Crane Summer Range, a nesting site of a remnant flock of whooping cranes, discovered in 1954.[23]

Bodies of water and tributaries[]

Rivers that flow into Great Slave Lake include (going clockwise from the community of Behchokǫ̀);[24][25]

- Emile River

- Snare River

- Wecho River

- Stagg River

- Yellowknife River

- Beaulieu River

- Waldron River

- Hoarfrost River

- Lockhart River

- Snowdrift River

- La Loche River

- Thubun River

- Terhul River

- Taltson River

- Slave River

- Little Buffalo River

- Buffalo River

- Hay River

- Mosquito Creek

- Duport River

- Marian Lake

- North Arm

- Yellowknife Bay

- Resolution Bay

- Deep Bay

- McLeod Bay

- Christie Bay

- Sulphur Cove

- Presqu'ile Cove

- Rocher River

- Frank Channel

Ice road[]

Great Slave Lake has one ice road known as the Dettah ice road. It is a 6.5 km (4.0 mi) road that connects the Northwest Territories capital of Yellowknife to Dettah, a small First Nations fishing community also in the Northwest Territories. To reach the community in summer the drive is 27 km (17 mi) via the Ingraham Trail.

Ice Lake Rebels[]

From 2014 to 2016, Animal Planet aired a documentary series called Ice Lake Rebels. It takes place on Great Slave Lake, and details the lives of houseboaters on the lake.[26]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Great Slave Lake". Geographical Names Data Base. Natural Resources Canada.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k Hebert, Paul (2007). "Encyclopedia of Earth". Great Slave Lake, Northwest Territories. Environmental Information Coalition, National Council for Science and the Environment. Retrieved December 7, 2007. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Jump up to: a b c "Google Maps Distance Calculator (From Behchoko to the Slave River Delta it is 203 km and from the Mackenzie River to the furthest reaches of the East Arm it is 469 km)". Retrieved December 22, 2014.

- ^ Nav Canada's Water Aerodrome Supplement. Effective 0901Z 26 March 2020 to 0901Z 22 April 2021.

- ^ "Grand lac des Esclaves". Geographical Names Data Base. Natural Resources Canada.

- ^ "Kw'ahtidee Jimmy Bruneau" (PDF). Northwest Territories. NWT Literary Council. Retrieved February 10, 2021.

- ^ Indigenous Risk Perceptions and Land-Use in Yellowknife, NT

- ^ Wohlberg, Meagan. "We Are T'satsąot'inę: Renaming Yellowknife". Edge North. Retrieved February 10, 2021.

- ^ Cohen, Sidney. "Big Lake". Up Here. Retrieved February 10, 2021.

- ^ Schertzer, William M.; Rouse, Wayne R.; Blanken, Peter D.; Walker, Anne E. (August 2003). "Over-Lake Meteorology and Estimated Bulk Heat Exchange of Great Slave Lake in 1998 and 1999" (PDF). Journal of Hydrometeorology. American Meteorological Society. 4 (4): 650. Bibcode:2003JHyMe...4..649S. doi:10.1175/1525-7541(2003)004<0649:OMAEBH>2.0.CO;2. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 13, 2012. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

The surface area of Great Slave Lake is 27,200 km2 with a total volume of 1,070 km3 (van der Leeden et al. 1990)

- ^ Great Slave

- ^ W.C. Noble (1981) "Prehistory of the Great Slave Lake and Great Bear Lake Region," In: Handbook of the North American Indians - Subarctic, Volume Six. Smithsonian Institution.

- ^ Waldman, Carl (2006). Facts on File Library of American History - Encyclopedia of Native American tribes. Infobase Publishing. p. 275. ISBN 9781438110103.

- ^ Pritzker, Barry (2000). A Native American encyclopedia : history, culture, and peoples. Oxford University Press. p. 512. ISBN 9780195138979.

- ^ "Yellowknife hotel with 'slave' in name stokes conversation on reclaiming Indigenous names".

- ^ Alexander Mackenzie. Voyages from Montreal, on the River St. Lawrence, through the continent of North America, to the Frozen and Pacific Oceans; in the years 1789 and 1793. With a preliminary account of the rise, progress, and present state of the Fur Trade of that country. London: Printed for T. Cadell, Jun, and W. Davis, Stand; Cobbett and Morgan, Pall-Mall; and W. Creech, at Edinburgh, by R. Noble, Old Bailey, 1801. pg. 3, footnote.

- ^ "Buffalo Jones". The Center for Humane Arts, Letters, and Social Sciences Online, Michigan State University. Archived from the original on March 6, 2012. Retrieved September 4, 2010.

- ^ Quentin Bristow. "Operation Morning Light". Natural Resources Canada. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved January 24, 2007.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Cohen, Sidney (September–October 2020). "Big Lake". Up Here. Vol. 36 no. 5. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ^ Mandeville, Curtis (June 21, 2016). "Goodbye Great Slave Lake? Movement to decolonize N.W.T. maps is growing". CBC News. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ^ Schertzer, W. M. (2000). "Digital bathymetry of Great Slave Lake". NWRI Contribution No. 00-257, 66 pp. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Hogan, C. Michael (2008), Stromberg, Nicklas (ed.), Black Spruce: Picea mariana, GlobalTwitcher.com, archived from the original on October 5, 2011

- ^ "Whooper Recount". University of Nebraska. Retrieved January 20, 2007.

- ^ "Natural Resources Canada-Canadian Geographical Names (Great Slave Lake)". Retrieved December 20, 2014.

- ^ "Atlas of Canada Toporama". Retrieved December 20, 2014.

- ^ "Ice Lake Rebels". Retrieved September 23, 2015.

Further reading[]

- Canada. (1981). Sailing directions, Great Slave Lake and Mackenzie River. Ottawa: Dept. of Fisheries and Oceans. ISBN 0-660-11022-9

- Gibson, J. J., Prowse, T. D., & Peters, D. L. (2006). "Partitioning impacts of climate and regulation on water level variability in Great Slave Lake." Journal of Hydrology. 329 (1), 196.

- Hicks, F., Chen, X., & Andres, D. (1995). "Effects of ice on the hydraulics of Mackenzie River at the outlet of Great Slave Lake, N.W.T.: A case study." Canadian Journal of Civil Engineering. Revue Canadienne De G̐ưenie Civil. 22 (1), 43.

- Kasten, H. (2004). The captain's course secrets of Great Slave Lake. Edmonton: H. Kasten. ISBN 0-9736641-0-X

- Jenness, R. (1963). Great Slave Lake fishing industry. Ottawa: Northern Co-ordination and Research Centre. Dept. of Northern Affairs and National Resources.

- Keleher, J. J. (1972). Supplementary information regarding exploitation of Great Slave Lake salmonid community. Winnipeg: Fisheries Research Board, Freshwater Institute.

- Mason, J. A. (1946). Notes on the Indians of the Great Slave Lake area. New Haven: Yale University Department of Anthropology, Yale University Press.

- Sirois, J., Fournier, M. A., & Kay, M. F. (1995). The colonial waterbirds of Great Slave Lake, Northwest Territories an annotated atlas. Ottawa, Ont: Canadian Wildlife Service. ISBN 0-662-23884-2

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Great Slave Lake (category) |

- Great Slave Lake pictures from Picsearch.com

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- "Great Slave Lake". The New Student's Reference Work. 1914.

- "Great Slave Lake". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- "Great Slave Lake". The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

- "Perspective on the Great Slave Lake Railway" Manuscript at Dartmouth College Library

- Lakes of the Northwest Territories

- Tributaries of the Mackenzie River